“The stone is a lethal weapon. Its spiritual violence will act like a cancer.”

— Kevin Davies, Vicar of Scotby, near Carlisle, England

Border Reivers doing what they did best: steal cattle. Original drawing by G. Cattermole, via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain.

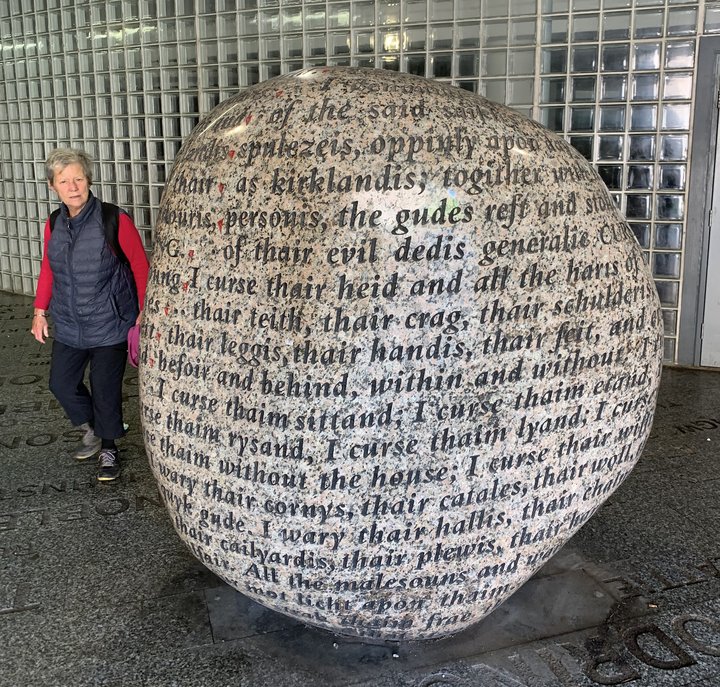

The stone in question is a five-foot diameter, ten-ton, polished granite boulder sitting in a gloomy underpass in Carlisle, northern England. On it is carved 383 words, a fraction of the original 1,069-word curse put on the Reiver people in 1525. The Reivers — raiders, thieves and cattle rustlers — terrorized the border country between England and Scotland (then an entirely separate nation) some 500 years ago, and the solution, apparently, was to (a) excommunicate them from the Church and (b) curse them. Which Gavin Dunbar, Archbishop of Glasgow, did in no-nonsense, lyrical terms:

I curse their head and all the hairs of their head; I curse their face, their brain, their mouth, their nose, their tongue, their teeth, their forehead, their shoulders, their breast, their heart, their stomach, their back, their womb, their arms, their leggs, their hands, their feet, and every part of their body, from the top of their head to the soles of their feet, before and behind, within and without. I curse them going and I curse them riding; I curse them standing and I curse them sitting; I curse them eating and I curse them drinking; I curse them rising, and I curse them lying; I curse them at home, I curse them away from home; I curse them within the house, I curse them outside of the house; I curse their wives, their children, and their servants who participate in their deeds. I curse their crops, their cattle, their wool, their sheep, their horses, their swine, their geese, their hens, and all their livestock. I curse their halls, their chambers, their kitchens, their stanchions, their barns, their cowsheds, their barnyards, their cabbage patches, their plows, their harrows, and the goods and houses that are necessary for their sustenance…

And on and on. It was read at the time, in full, from every church pulpit in the diocese. It’s a fine curse, making contemporary “screw you” type expletives seem trite, unimaginative and half-hearted. It’s a curse for the ages — so much so that, when the city was visited by a series of misfortunes in the years following the stone’s installation in 2001 (part of the city’s millennium celebrations), many locals called for it to be removed. Or exorcised. Or smashed to pieces. Or all three.

The curse stone in a Carlisle underpass. Photo: Barry Evans.

The misfortunes included: A fire at a local bakery; job losses at the coleslaw factory; an outbreak of foot-and-mouth disease; floods; and — saving the worst for last — the relegation (demotion) of Carlisle United, the local soccer team. (The stone’s designer, Gordon Young, is on record as saying that he would have smashed it himself years ago if he thought it had affected the fortunes of Carlisle United.)

Hence the calls for something to be done, including a plea by the local bishop to his boss, the Archbishop of Glasgow, to lift the curse. The Archbishop’s spokesman told the Guardian, “The Archbishop may send a letter offering his good wishes but he won’t be getting his Latin prayer book and his holy water and heading down the M74.” (The M74 being the local equivalent of 101.)

To date, calls for the stone’s removal have gone unheeded, and it just sits there, perhaps emanating bad vibes over the city. Or not. We just admired it and felt quite blessed to be in its presence. Such is the power of a good curse.

CLICK TO MANAGE