PREVIOUSLY:

###

Welcome

back for the second episode of Land Use and You, a new series that

explores the latest in cutting edge and good old fashioned land use

policy. Last month we explored how bringing back traditional small

lots (and the small single-family homes that go along with them) can

help Humboldt’s housing affordability crisis. Recent news from

Sacramento is also assisting in this effort: SB 9, a bill that would

allow lot splits in all single-family zones in California, has been approved by both houses of the State Legislature and is heading to

the Governor’s desk for signature. If the bill is signed into law

this fall, this important housing creation tool will be available

throughout all of the cities and towns in Humboldt County (and not

just in Eureka).

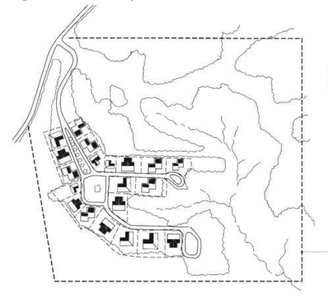

This month, however, we turn our attention to the country-fried cousin of the small-lot subdivision: the conservation subdivision. A conservation subdivision is one in which new homes are clustered together in one portion of the overall site so that a large area of forest, gulch, or agricultural land can be preserved as-is into the future. Conventional subdivisions, in contrast, attempt to spread all of the houses out evenly which often leaves little in the way of open greenspace.

It might look kinda like this.

Conservation

subdivisions (also called cluster subdivisions) were originally

created for farmland preservation purposes. People were displeased to

see entire farms, one after another, turned from crops to suburban

tract homes. Seeking a compromise, the conservation subdivision

offered a way to build the same number of homes while preserving 50%

or more of the land.

Applied

in the context of Humboldt County, this development pattern offers

the same advantages and more. The following are some of the reasons

why your next subdivision might best be a conservation subdivision.

Hard-to-Develop Parcels. Most land available for purchase today in Humboldt is hard to build on. Read the fine print on most ads and you’ll often see the majority of the property consists of steep slopes, creeks, and wetlands. Attempting to develop on top of site constraints such as these can be impossible to permit (sometimes prohibited by law) or ruinously expensive (imagine custom engineered foundations and enormous retaining walls). A conservation subdivision allows you to carefully arrange homes on the portions of the lot that are actually realistically buildable.

Lower Utility Infrastructure Costs. Clustering development in one portion of the site means that you’ll need to construct less lineal feet of water/sewer pipe, curb/gutter, and asphalt streets. This can mean the difference between a development that pencils out — and one that doesn’t.

Minimum Lot Size. Conservation subdivisions can have very small lot sizes. A new two-story, 2,000 square-foot house might be built on a 2,000 square-foot lot. Lot coverage might exceed 80 percent. Ordinarily, figures like this would only be seen on dense development in urban areas. However, in the context of conservation subdivisions these compact standards are required to facilitate a development that works with the unique local site constraints.

Number of Lots. A conservation subdivision can result in as few as two lots (i.e. a lot split) all the way up to 100+ lots for a large development.

House Size and Setbacks. Home sizes in conservation subdivisions are often the same square footage as in conventional subdivisions. Building setbacks, however, tend to be a bit shorter and yards minimal. For example, the front of a house in a conservation subdivision might sit closer to the street on account of the steep gulch drop-off at the back of the lot. Correspondingly, the home’s “backyard” might consist of nothing more than a large wraparound deck (w/outdoor kitchen and hot tub) that looks out over a private (and protected) view of the gulch.

Overall Density. The overall density of a conservation subdivision is no different than a conventional subdivision. Density is expressed in the General Plan as the number of homes allowed per acre. For example, a four acre parcel subject to a maximum density of eight dwelling units per acre can only contain thirty-two homes total. A conventional subdivision might result in 32 5,000 square-foot lots whereas a conservation subdivision might create 32 2,500 square-fool lots and 2.2 acres of open space.

Conservation Area Requirements. In order to qualify for the compact development standards of a conservation subdivision, a minimum percentage of the total site area must be permanently set aside for open space, recreation, agricultural, or habitat conservation purposes. In Eureka, the minimum is 50%. The conservation area must be protected from future development by dedicating a conservation easement to a public agency or public interest land trust, by dedicating the land in fee-title to a public agency, or by recording a deed restriction. At the discretion of the developer, the conservation area can be opened for use by the general public or reserved for private use by the residents of the development. Gulches are great places for shared walking trails. On farmland, the conservation area can remain in production or be repurposed to community garden space for residents of the development (or heck, open to anyone).

Affordability.

Conservation

subdivisions result in brand-new, market rate homes — which are not

cheap. That’s okay. Humboldt needs more housing at all income

levels. Building more market rate housing doesn’t mean that we’re

building less affordable housing. Just think — that Santa

Rosa-based gastroenterologist considering moving to Humboldt just

might be tempted by a nice new home created via a conservation

subdivision.

Well,

there you have it, the key takeaways of conservation subdivisions.

Ask for them by name.

If for some reason your town doesn’t allow conservation subdivisions, be advised that amending the zoning code to allow them need only take a few months. Remember, conservation subdivisions don’t increase density beyond what is already allowed in the General Plan. Call your representative and explain why you think conservation subdivisions should be allowed.

###

Brian Heaton is a local pro-housing advocate with a professional background in city planning. Views expressed are his own and do not represent those of any government.

CLICK TO MANAGE