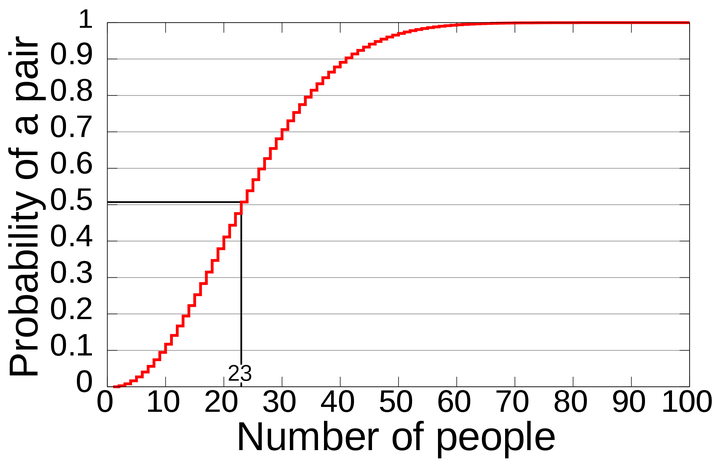

When dealing with probabilities, our intuition, or gut feeling, is easily fooled. F’rinstance, you may be familiar with the “birthday paradox” — not really a paradox, it just seems so. Imagine you’re at a party with 22 other people. You announce what day and month your birthday falls on. Then a second person does the same. And so on until everyone has stated their birthday. Turns out, in a room of 23 people, the odds of two of you sharing the same birthday are better than 50/50. It seems paradoxical because you’re putting 23 people up against 365 days in a year.

Here’s how it works. (Skip what follows if you hate math.) In a group of 23 people, there are 253 one-on-one comparisons to make (22 + 21 + … + 1), that is, 253 chances for matching birthdays. The chance of two people not having matching birthdays is 364/365, so with 23 people having 253 chances of matching birthdays, the chance of no matches is (364/365)^253, or slightly less than 50%. QED.

Graphic: Rajkiran g, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.

Another non-intuitive probability is taken seriously by a couple of my “fear of flying” friends, otherwise perfectly sensible and rational people. I point out that the average American has about a 1 in 11 million chance of dying in a plane crash in any one year (—they’d have to fly every day for 10,000 years before having a 50/50 chance of being in a crash). They’re unmoved. “Maybe,” they say, “but my odds are 1 in infinity, so long as I don’t fly.” “But you drive, and your annual odds are about 1 in 5,000 of dying in a car accident,” I’ll say.

It’s more nuanced than that, of course. In a plane, we’re essentially passive cargo. But when we drive, we’re in charge, and even passengers can see where they’re going. Flying, we have to have faith that the folks up front know what they’re doing. (They do.) Following 9/11, some of that faith was lost: fewer people flew and more drove, which probably accounts for the additional 700-1,000 people who died in vehicle crashes from October through December, 2001, as compared to the same months in 2000.

Then there’s the awareness aspect. Plane crash = headlines; car crash = meh. The media teaches us to be far more scared of plane crashes than car crashes, and while our brains may be skeptical, our guts don’t work that way. (Similarly, our media hypes mass shootings, yet over 99% of U.S. gun deaths — 45,222 in 2020 — are unrelated to mass shootings, according to the CDC. Most are suicides.)

How each of us deals with odds depends, not only on understanding the math, but also on our individual personalities. Are you, for instance, a risk-averse Volvo driver or a risk-loving freestyle rock climber? Here’s an easy test: I offer you a choice: $20 or — depending on a coin toss — either $40 (heads) or $0 (tails). Which do you take? Me, I’d go with the second choice (and have, in the past, to my net benefit).

Now you’re up on probability, here’s a tricky one. You’re shown two urns, one of which contains one black and one white ball; the other contains two black balls. You pick one urn at random and put your hand in, pulling out one ball: it’s black. What’s the probability that the second ball in that urn is also black? (I’ll post the answer in the “comments” section of LoCO tomorrow, Monday.)

CLICK TO MANAGE