[Just discovering this LoCO feature?

Find the beginning by clicking here.]

CLEAN BREAK

by

Lionel White

CHAPTER TWO

1

He’s changed, she thought.

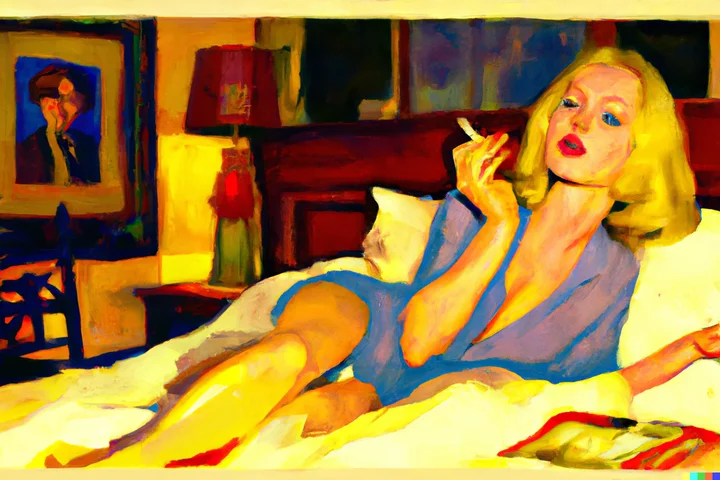

Stretching out her slender, naked arm, she reached over to the night table at the side of the bed and fumbled around until she found the pack of cigarettes. She brought it over to herself and hunched up so that she was half sitting. She shook out a cigarette and then leaned over again to find the lighter. With the lights out, the room was only half dark as the mid afternoon sun filtered through the almost closed venetian blinds.

She lit the cigarette and drew a deep lungful of smoke, slowly expelling it. Her eyes went to the man lying beside her. His own eyes were closed and he lay completely still, but she knew that he wasn’t sleeping.

Once more she thought, he’s changed. It was odd, but something about him was different. Physically, the four years hadn’t seemed to have altered his appearance in the slightest. There was, of course, that new touch of gray over his ears. But he was still a lean, hard six feet one, his face still carried the sharp fine lines, his gray eyes were as clear and untroubled as they had always been. No, the change wasn’t a physical one.

For that she was glad. She wouldn’t have been able to stand it if those four years had done to him what they do to most men who go to jail and come out shattered and embittered.

Johnny had been right about one thing; he had done it on his ear. He’d taken the rap and put it away and he hadn’t let it hurt him.

No, it wasn’t a physical change. It was something far more subtle. Not that the time behind bars had soured him. It hadn’t even taken that almost boyish optimism and wild enthusiasm from him.

He still talked the same and acted the same. He was still the same old Johnny. Except that in some way or another he seemed to have settled down. Now, there was a new, deep, serious undercurrent to him which hadn’t been there before. A sort of grim purposefulness which he had always lacked.

It was as though he had finally grown up.

Her hand went across to him and she softly rubbed the side of his head. He didn’t move and instinctively she leaned over and kissed him gently on the mouth.

God, she was just as crazy about him as she had always been. More so. She was glad now that she had waited.

Four years had been a long time, a hell of a long time. For a moment she wondered what those years might have done to her. But at once, she dismissed the thought. Whatever they had done, it hadn’t seemed to bother Johnny at all. He was just as much in love with her as he had always been. Just as impetuous and just as demanding. It was one of the things which made her always want him and need him—his constant demand for her.

Twisting her lovely, long limbed body, she put her feet on the floor at the side of the bed and sat up.

“It’s getting late, Johnny,” she said. “Must be after four. I’ll get dressed and make us a cup of coffee. You suppose this man has any coffee around the place?”

He opened his eyes wide then, and looked around at her. He smiled.

“Come on back,” he said.

She shook her head and the shoulder length blonde hair covered the side of her face.

“Not on your life, baby,” she said. “You get up now and get dressed. I want to be well out of here before this Unger character gets home.”

He grunted.

“Guess you’re right, honey. You hit the bathroom; I’ll be up in a second. There’s a coffeepot in the kitchen. See if you can find something for a couple of sandwiches.”

He reached for a cigarette from the package she had replaced on the table. The girl stood up and crossed the room toward the bath. She reached and took a handful of clothes from the back of a chair as she passed. A moment later the door closed behind her.

Flicking an ash on the floor, he thought, God it was worth waiting for. Worth every bitter second of those four years.

When he heard the sound of the shower, he too got up. He pulled on his clothes carelessly and was tucking in his shirt as she once more returned to the room.

“Honey,” he said, looking at her with the admiration still deep on his face, “honey, listen. The hell with the coffee. Run down to the corner and pick up a bottle of Scotch. Jesus, I feel like a drink. I want to celebrate. After four years, I feel like something a little stronger than coffee.”

She looked at him silently for a second and then spoke.

“You sure it’s a good idea—drinking?” she asked.

He smiled.

“You don’t have to worry,” he said. “Nobody ever had to worry about my drinking. It’s just that I feel like celebrating.”

“Well,” she said, slowly, “all right, Johnny. You know what you want. The only thing is, remember, it’s been four years and it’s likely to hit you awful fast. You want to be wide awake for tonight.”

He nodded, at once serious.

“I’ll be wide awake,” he said. “Don’t worry—I’ll be plenty wide awake.”

She smiled then, and pulling on the little cardinal’s hat, she sort of half shook her head to brush the hair back and turned toward the door.

“Be right back,” she said.

“Wait,” he said, “I’ll get you some money.”

“I’ve got money,” she said and quickly opened the door and closed it behind her.

Johnny Clay frowned and sat in the straight-backed chair next to the window. He thought of the single five dollar bill which Marvin Unger had left him that morning—just in case. He laughed, not pleasantly.

“Tight bastard,” he said, under his breath.

But at once his mind went back to Fay. Jesus, there was a million things he wanted to ask her. They hadn’t hardly talked at all. There were so many things they had to tell each other. Four years is a long time to cover in a few minutes.

Of course he knew that she still had the job; that she still lived with her family out in Brooklyn. She hadn’t had to tell him that she had waited for him and only him all these years. That he knew, unasked. Her actions alone had told him.

And he’d had damned little opportunity to tell her much. He’d only just briefly outlined his plans; told her what he had in mind.

He knew she wouldn’t like the idea. Certainly she had felt bad enough about it that time, more than four years ago, when the court had passed sentence on him and he’d started up the river. And she’d always been after him to get an honest job, to settle down.

Yes, he’d been surprised when she hadn’t started right in to make objections.

After he had told her about it, she’d been quiet for a long time. And then, at last, she’d said, “Well, Johnny, I guess you know what you’re doing.”

“I know,” he’d told her. “I know all right. After all, I’ve had four years—four damned long years, to think about it. To plan it.”

She nodded, looking at him with that melting look which always got him.

“Just be sure you’re right about it, Johnny,” she said. “Be awful sure you’re right. It’s robbery, Johnny. It’s criminal. But you know that.”

“I’m right.”

There’d been no questions about the right or wrong of it. That part she understood. Right now she was too happy in being with him, in loving him, to go into it.

“The only mistake I made before,” he’d told her, “was shooting for peanuts. Four years taught me one thing if nothing else. Any time you take a chance on going to jail, you got to be sure that the rewards are worth the risk. They can send you away for a ten dollar heist just as quick as they can for a million dollar job.”

But then, they hadn’t talked any more. They had other things to do. More important things.

He had the ice cubes out and a couple of glasses on the table when she returned. She tossed her tiny hat on the bed and then sat on the edge of it as he fixed two highballs with whiskey, soda and ice. Silently they touched rims and then sipped the drinks.

Looking at him with a serious expression in her turquoise eyes, she said, “Johnny, why don’t you get out of this place? It’s depressing here; dingy.”

He shook his head.

“It’s the safest place,” he said. “I have to stay here. Everything now depends on it.”

She half shook her head.

“This man Unger,” she said. “Just how…”

He interrupted her before she could finish the question.

“Unger isn’t exactly a friend,” he said. “He’s a court stenographer down in Special Sessions. I’ve known him for a number of years, but not well. Then, at the time my case came up and I was sentenced, he looked me up while I was waiting to be transferred to Sing Sing. He wanted me to get a message through to a man who was doing time up there, in case I had a chance to do so. It turned out I did.

“When I got out I figured he sort of owed me a favor. I looked up his name in the phone book and called him. We got together and had dinner. I was looking around for a guy like him—a guy who’d be a respectable front, who had a little larceny in his heart and who might back the play. I felt him out. It didn’t take long.”

Fay looked at him, her eyes serious.

“Are you sure, Johnny,” she asked, “that he isn’t just playing you along for a sucker? A court stenographer…”

Johnny shook his head,

“No—I know just where he stands. The man isn’t a crook in the normal sense of the word. But he’s greedy and he’s got larceny. I was careful with him and played him along gradually. He’s all right. He went for the deal hook, line and sinker. He’s letting me lay low here, he’s making my contacts, arranging a lot of the details. He’s going to cut in for a good chunk of the dough, once we get it. He won’t, of course, be in on the actual caper itself. But he’s valuable, very valuable.”

Fay still looked a little doubtful.

“The others,” she said, “they all seem sort of queer.”

“That’s the beauty of this thing,” Johnny told her. “I’m avoiding the one mistake most thieves make. They always tie up with other thieves. These men, the ones who are in on the deal with me—none of them are professional crooks. They all have jobs, they all live seemingly decent, normal lives. But they all have money problems and they all have larceny in them. No, you don’t have to worry. This thing is going to be foolproof.”

Fay nodded her blonde head.

“I wish there was something I could do, Johnny,” she said.

Johnny Clay looked at her sharply and shook his head.

“Not for a million,” he said. “You’re staying strictly out of this. It was even risky—dangerous—for me to let you come up here today. I don’t want you tied in in any possible way.”

“Yes, but… “

He stood up and went to her and put his arms around her slender waist. He kissed the soft spot just under her chin.

“Honey,” he said, “when it’s over and done with, you’ll be in it up to your neck. We’ll be lamming together, baby, after all. But until it’s done, until I have the dough, I want you out. It’s the only way.”

“If there was only something… “

“There’s plenty you can do,” he again interrupted. “Get that birth certificate of your brother’s. Get a reservation for those plane tickets. Begin to spread the story around your office about planning to get married and give them notice. You got plenty to do.”

He looked over at the cheap alarm clock on the dresser.

“And in the meantime,” he said, “you better get moving. I don’t want to take any chances on Unger walking in and finding you here.”

She stood up then and put her second drink down without tasting it.

“All right, Johnny,” she said. “Only—only when am I going to see you again?”

He looked at her for a long moment while he thought. He hated to have her leave; he hated the idea that he couldn’t go with her, then and there.

“I’ll call you,” he said. “As soon as I can, I’ll call. It will be at your office, sometime during the first part of the week.”

They stood facing each other for a moment and then suddenly she was in his arms. Her hands held the back of his head as she pressed against him and her half opened mouth found his.

She left the room then, two minutes later, without speaking.

# # #

2

It was exactly six forty-five when George Peatty climbed the high stoop of the brownstone front up on West a Hundred and Tenth Street. He took the key from his trouser pocket, inserted it and twisted the doorknob. He climbed two flights of carpeted stairs and opened the door at the right. Entering his apartment, he carefully removed his light felt hat, laid it on the small table in the hall and then went into the living room. He still carried the half dozen roses wrapped up in the green papered cornucopia.

About to open his mouth and call out, he was suddenly interrupted by the sound of a crash coming from the bedroom. A moment later he heard laughter. He passed through the living room and down the hallway to the bedroom. He wasn’t alarmed.

Bill Malcolm was down on his knees on the floor, at the end of the big double bed, beginning to pick up the pieces of broken glass. The uncapped gin bottle was still in his right hand, carried at a dangerous angle. He had a foolish grin on his handsome face and George knew at once that he was drunk.

Betty, Malcolm’s short, chubby wife, sat on the side of the bed. She was laughing.

Sherry was over by the window, fooling with one of the dials on the portable radio. There was a cigarette between her perfect red lips and she held a partly filled glass in her hand. She was dressed in a thin, diaphanous dressing gown and her crimson nailed feet were bare.

Instinctively, George knew that she was sober—no matter how much she may have had to drink. She looked up the moment George reached the door, sensing his presence.

“My God, George,” she said, “take the bottle out of Bill’s hand before he spills that too. The dope is drunk.”

“He’s always drunk,” Betty said. She stood up and weaved slightly as she moved toward her husband.

“Come on, Bill,” she said, her voice husky. “Gotta go.” She reached over and took the bottle and put it down on the floor. “My God, you’re a clumsy …”

“Oh, stay and have another,” Sherry said. “George, get a couple more glasses…”

Bill reached his feet, wobbling.

“Nope,” he said, thickly. “Gotta go. Gotta go now.” He lurched toward the door.

“Hiya, Georgie boy,” he said as he passed Peatty. “Missed the damn party.”

Betty followed him out of the room and a moment later they heard the slam of the outside door.

George Peatty turned to his wife.

“My God, Sherry,” he said, “don’t those two ever get sober?”

Even as he said the words, he knew he was doing the wrong thing. He didn’t want to argue with her and he knew that any criticism of the Malcolms, his wife’s friends from downstairs, always led to a fight. It seemed that lately anything he said upset Sherry.

Sherry looked at her husband, the long, theatrical black lashes half closed over her smoldering eyes. Her body, small, beautifully molded, deceptively soft, moved with the grace of a cat as she went over to the bed and curled up on it.

At twenty-four, Sherry Peatty was a woman who positively exuded sex. There was a velvet texture to her dark olive skin; her face was almost Slavic in contour and she affected a tight, short hair cut which went far to set off the loveliness of her small, pert face.

“The Malcolms are all right,” she said, her husky voice bored and detached. “At least they have a little life in them. What am I supposed to do—sit around here and vegetate all day?”

“Well …”

“Well my fanny,” Sherry said, anger now moving into her tone. “We don’t do anything. Nothing. A movie once a week. My God, I get tired of this kind of life. I get tired of never having money, never going anywhere, doing anything. It may be all right for you—you’ve had your fling.”

Her mouth pouted and she looked as though she were about to cry.

George heard the words, but he wasn’t paying attention to them. He was thinking that she was still the most desirable woman he had ever known. He was thinking that right now to her, to go over and take her in his arms and make love to her.

He held the flowers out in a half conciliatory gesture.

Sherry took them and at once put them down unopened. She looked up at her husband. Her eyes were cold now and wide with resentment.

“This dump,” she said. “I’m damned tired of it. I’m tired of not having things; not having the money to do things.”

He went over and sat on the side of the bed and started to put his arm around her. Quickly she brushed it away.

“Sherry,” he said, “listen Sherry. In another week or so I’m going to have money. Real money. Thousands of dollars.”

She looked at him with sudden interest but a second later she turned away.

“Yeah.” Her voice was heavy with sarcasm. “What—you got another sure thing at the track? Last time you had one it cost us two weeks pay!”

For a long minute he looked at her. He knew he shouldn’t say anything; he knew even one word would be dangerous. That if Johnny were to learn he had talked, he’d be out. That would be the very least he could expect. He could also be half beaten to death or even killed. But then again he looked over at Sherry and he was blinded to everything but his desire for her. That and the realization that he was losing her.

“Not a horse,” he said. “Something a lot bigger than any horse. Something so big I don’t even dare tell you about it.”

She looked up at him then from under the long lashes with sudden curiosity. She reached over and her body pressed against his.

“Big?” she said. “If you’re serious, if this isn’t just another of your stories, then tell me. Tell me what it is.”

Again he hesitated. But he felt her body pressing against his and he knew that he’d have to tell her sooner or later. She’d have to know sometime. Well, the hell with Johnny. The reason he was in on the thing anyway was because of Sherry and his fear of losing her.

“Sherry,” he said, “I’ll tell you, but you’ll have to keep absolutely quiet about it. This is it—the real thing.”

She was impatient and started to pull away from him.

“It’s the track all right,” he said, “but not what you think. I’m in with a mob—a mob that’s going to knock over the track take.”

For a moment she was utterly still, a small frown on her forehead. She pulled away then and looked at him, her eyes wide.

“What do you mean?” she said. “The track take—what do you mean?”

His face was pale when he answered and the vein was throbbing again in his neck.

“That’s right—the whole track take. We’re going to knock over the office safe.”

She stared at him as though he had suddenly lost his mind. “For God’s sake,” she said. “George, are you hopped up? Are you crazy? Why my God…”

“I’m not crazy,” he said. “I’m cold sober. I’m telling you—we’re going to hijack the safe. We’re meeting tonight to make the plans.”

Still unbelieving, she asked, “Who’s meeting? Who’s we?”

He tightened then and his mouth was a straight contrary line.

“Gees, Sherry,” he said, “that I can’t tell you. I can only say this. I’m in on it and it’s big. Just about the biggest thing that has ever been planned. We’re…”

“The track,” she said, still unbelieving. “You and your friends must be insane. Why, nobody’s ever knocked off a whole race track. It can’t be done. Good God, there’s thousands of people—hundreds of cops… George, you should know—you work there.”

He looked stubborn then when he spoke.

“It can be done,” he said. “That’s just the thing; that’s the beauty of it. It hasn’t been done or even tried and so nobody thinks it’s possible. Not even the Pinkertons believe it could be worked. That’s one reason it’s going to work.”

“You better get me a drink, George,” Sherry suddenly said. “Get me a drink and tell me about it.”

He stood up and retrieved the gin bottle from the floor. Going out to the kitchen, he mixed two Martinis. He wanted a couple of minutes to think. Already he was beginning to regret having told her. It wasn’t that he didn’t trust Sherry—he knew she’d keep her mouth shut all right. But he didn’t want her worrying about the thing. And of course, Johnny was right. No one at all should know about it except the people involved. Even that was risky enough.

He reflected that even he didn’t know exactly who was in on the plot. Well, he’d learn tonight—tonight at eight o’clock.

Carefully carrying the glasses, he started for the bedroom. He decided that he’d tell Sherry nothing more, nothing at all. He had to keep quiet, not only for his own protection, but for her protection as well. But he felt good about one thing. Sherry knew, now, that there was a chance they’d be coming into a big piece of money. She’d be happier. A lot happier. With money he could get her back; really back.

Before George Peatty left the house to take a subway downtown to keep his appointment, he took off his jacket and tie and went into the bathroom to wash up. While he was out of the room, Sherry crossed over to where he had carefully dropped his coat over the back of a chair. She made a quick, deft search through his pockets. She found the slip of paper on which he had scribbled the address down on East Thirty-first Street so that he would be sure not to forget it.

Quickly she memorized the few words and then put the paper back in his pocket.

She was back on the bed when he returned and she tolerated his long kiss and caress before he left.

# # #

3

Number 712 East Thirty-first Street was an old law tenement house which had been built shortly after the Civil War. Countless generations of refugees from the old world had been born, brought up and died in its dingy, unsanitary interior. Around 1936 the building had been officially condemned as a fire trap, although it had been unofficially recognized as one for several decades, and ultimately evacuated. A smart real estate operator picked up the property and making use of a lot of surplus war material purchased for almost nothing, he rebuilt the place into a more or less modem apartment house. The apartments were all the same, two rooms, a bath and a kitchenette. There were four to a floor and the five floors of the building were served by an automatic, self-service elevator. The facade of the building had been refinished and it looked respectable.

Rents went up from $25 a month to $70 and the new landlord had no difficulty at all in filling the place, what with the critical housing shortage. In spite of his improvements, however, the building remained pretty much of a fire trap and it also remained, to all intents and purposes, a tenement house.

Marvin Unger was one of the first to move into the structure.

Getting off the train from Long Island, Unger looked up at the clock over the information booth and saw that it was shortly before six. He decided against going directly to his apartment, and went over and bought an evening paper with the final stock market quotations and race results. Folding the paper and carrying it under his arm, he left the station and walked north until he came to a cafeteria. He entered and took a tray. Minutes later he found a deserted table toward the rear. He put his food down, carefully placed his hat on the chair next to himself and opened up the newspaper. He didn’t bother to look at the race reports. He turned to the market page and began to check certain stock figures as he started to have his dinner.

At a time when almost every amateur speculator was making money on a rising market, Unger had somehow managed to lose money. A frugal man who lived by himself and had no expensive habits, he had saved his money religiously over the years. He invested the slender savings in stocks, but unfortunately, he never had the courage to hang on to a stock once he had bought it. As a result he was constantly buying and selling and, with each flurry of the market, he changed stocks and took losses on his brokerage fees. He also had an almost uncanny ability to select the very few stocks which went down soon after he bought them. Of the several thousand dollars he had managed to scrimp and put away from his small salary over the years, he had almost nothing left.

He finished his dinner and went back to the counter for a cup of coffee.

A few minutes later he started to walk across town in the direction of his apartment. He passed a delicatessen on his way and stopped in. He ordered two ham and cheese sandwiches and a bottle of milk. For a moment he hesitated as he considered adding a piece of cake, but then he shook his head. What he had would be enough. There was no reason to pamper the man. God knows, this thing was costing him enough, both in time and in money, as it was.

The street door to the apartment house was unlocked, as it usually was until ten o’clock at night. He passed the row of mailboxes without stopping at his own. He never received mail at his residence and in fact, almost no one knew where he lived. He had not bothered to change the records down at the office giving his latest address the last time he had moved. He had an almost psychological tendency toward secrecy; even in things where it was completely unimportant.

He took the self-service elevator to the fourth floor and got out. A moment later he knocked gently on his own door.

Johnny Clay had a half filled glass in his hand when he opened the door.

Unger entered the dingy, sparsely furnished apartment and the first thing he noticed was the partly emptied bottle of Scotch sitting on the table in the small, square living room. He looked up at the other man sourly.

“Where’d you get the bottle?” he asked. At the same time he walked over and picked it up, reading the label.

Johnny frowned. The faint dislike he had felt for the other man from the very first was rapidly developing into a near hatred.

He resented the very fact that he was forced to stay in Unger’s dismal, uncomfortable place; he hated his dependence on him. But at once he reflected that an out-and-out argument was one thing which must be avoided at all costs. He couldn’t afford to fight.

“Don’t worry,” he said, avoiding a direct answer, “I don’t get drunk. I just got tired of sitting around with nothing to do. Why the hell don’t you get a television set in this place. There isn’t even a book around to read.”

Unger set the bottle back on the table.

“Was Sing Sing any pleasanter?” he asked, his voice nasty. “I asked where you got the bottle.”

“God damn it, I went down to the corner and bought it,” Johnny said. “Why—do you object?”

“It isn’t a case of objecting,” Unger said. “It’s just that it was a risky thing to do. The reason we decided you’d stay here is because it’s safe. But it’s only safe if you stay inside. Don’t forget—you’re on parole, and right now you’re disobeying the terms of the parole. The minute you moved and quit that job, you left yourself wide open to being picked up.”

Johnny started to answer him, to call him on it, but then, a moment later, thought better of it.

“Look, Unger,” he said, “let’s you and me not get into any hassle. We got too much at stake. You’re right, I shouldn’t show myself. On the other hand, a guy can go nuts just hanging around. Anyway, I’m hungry and there’s nothing around the place. You bring me anything?”

Unger handed him the bottle of milk and the sandwiches.

“Care for a drink?” Johnny asked.

Unger shook his head.

Going to wash up,” he said. He started for the bathroom.

Johnny took the brown paper bag containing the food into the kitchen. His eyes quickly went around to make sure that he had left no signs of Fay’s having been in the place. He didn’t want to have to explain Fay to anyone.

In fairness he had to admit that Unger was right. If the man believed that he had been out of the place, he had a right to squawk. But at the same time, he resented the other man and his attitude. Christ, if Unger wasn’t so damned tight, he’d make it a little more attractive for Johnny to stay put.

Marvin Unger rolled up his sleeves and turned on the cold water faucet in the washbasin. He started to lean down to wash his face and abruptly stopped halfway. The bobby pin was lying next to the cake of soap where he couldn’t possibly have missed it. His face was red with anger as he picked it up and looked at it for a long moment.

“The fool”“ he said. “The stupid fool.”

He put the bobby pin in his pocket and decided to say nothing about it. He, as well as Johnny, realized that they could not afford to have an open rupture.

For the first time he began to regret that he’d gotten mixed up in the thing in the first place. If anything went wrong, he said to himself bitterly, it would only serve him right. Serve him right for getting mixed up with an ex-convict and his crazy plans.

Thinking of those plans, he began to visualize his share of the profits if the deal turned out successful. It would be a fabulous sum. A sum he would never be able to make working as a court stenographer.

He shrugged his shoulders then, almost philosophically. If he was going to make crooked money the least he could expect was to be mixed up with crooks. Anyway, it would be over and done with soon. Once he had his cut, he’d make a clean break. The hell with the rest of them; he didn’t care what happened to them.

Where he’d be none of them would ever reach him. And it wouldn’t matter too much if the cops got onto them and they were picked up and talked. By that time Marvin Unger would have found a safe haven and a new identity. By that time he would be set for the rest of his life.

He turned back to the living room, determined to make the best of things until it was over and done with.

Johnny was munching the last of a sandwich as Unger went over to the hard leather couch and sat down.

“Everything went all right,” he said. “Got the message to both of them.”

Johnny nodded.

“Good.”

“To tell you the truth,” Unger said, “I wasn’t much impressed with the bartender. He looked soft. The other one, the cashier, didn’t seem quite the type either.”

“I didn’t pick them because they’re tough,” Johnny said. “I picked them because they hold strategic jobs. This kind of a deal, you don’t need strong arm mugs. You need brains.”

“If they have brains what are they doing…”

“They’re doing the same thing you are.” Johnny said, foreseeing the question. “Earning peanuts.”

Unger blushed.

“Well, I hope you’re sure of them,” he said.

“Look,” Johnny said, “I know ‘em both—well. Mike—that’s the bartender, is completely reliable. He’s been around for a long time. No record and a good reputation. But he wants money and he wants it bad. He’s like you and me—he no longer cares where it comes from, just so he gets it. He can be counted on.

“The other one, Peatty, is a different proposition. Frankly, I wouldn’t have picked him for this deal except for one thing. He happens to be a cashier at the track and he knows the routine. He knows how the dough is picked up after each race, where it is taken and what’s done with it. We had to have a guy on the inside. George has no criminal record either—or he wouldn’t be working at the track. He used to be pretty wild when he was a kid, but he never got into any serious trouble. He may be a little weak, but hell, that doesn’t matter. After all, we already agreed on one thing. The big trick is to actually get away with the money. Once we’re clear, once we have the dough, then it’s every man for himself.”

Unger nodded.

“Yes,” he said, “every man for himself. How about the other one—the cop?”

“Randy Kennan? Randy’s one guy we don’t have to worry about at all. He’s not too smart, but you can count on him. He’s a horse player and a skirt chaser, he puts away plenty of liquor, but he’s no lush. His record in the department is all right. But he needs money to keep up his vices. I’ve known Randy for a long time. We were brought up together. In spite of the rap I took, we’re still friends. No, Randy’s O.K. You won’t have to give him a second thought.”

Unger looked thoughtful.

“But a cop,” he said. “Jesus Christ. You’re sure there’s no chance he’s just playing along with some idea of turning rat and getting himself a nice promotion?”

Not a chance in the world,” Johnny said. “I know him too well…” He thought for a moment, then added, “It’s possible, of course, the same as it’s possible you could do the same thing. But it doesn’t make sense. You wouldn’t throw over a few hundred grand to get a four hundred dollar a year raise, would you?”

Unger didn’t say anything.

“One thing,” Johnny said, “I learned in prison is this. There isn’t a professional criminal who isn’t a rat. They all are. They’d turn in their best friend for a pack of butts—if they needed a cigarette. Get mixed up with real criminals and you’re bound to mess up a deal. That’s the main reason I think this caper has a good chance of working. Everybody involved, with the exception of myself, is a working stiff without a record and a fairly good rep. On this kind of a heist, the first thing the cops are going to look for is a gang of professionals. The only one with a record is myself. And I’m in it because it was my idea.”

He looked over at the other man, his eyes cynical. “There is another thing, too,” he added, “that I’ll say about myself. I never hung out crooks; never got mixed up with them. I’ve never been tied in with a job anything like this one. I’d be the last guy on the books the law would think of after this thing is pulled.”

“I hope so,” Unger said. “I certainly hope so.”

“You want to remember also,” Johnny said. “Anyone of us crosses us up, he’s in just as deep as the rest of us. It won’t be a case of the testimony of a bunch of criminals which will involve him; it’ll be the testimony of honest working stiffs. You can rest easy about the boys—the only chances we take in the whole thing is the actual execution of the job itself.”

Marvin Unger nodded, his eyes thoughtful. He took a cigar out of his breast pocket and neatly clipped off the end and put it between his thin lips. He was striking the match when the knock came on the door.

Instinctively both men looked over at the alarm clock. The hands pointed to eight exactly.

# # #

Tune in next week for the next chapter of Clean Break!

Stark House Sunday Serial is brought to you by the Lost Coast Outpost and Stark House Press.

Based in Eureka, California since 1999, Stark House Press brings you reprints of some of the best in fantasy, supernatural fiction, mystery and suspense in attractive trade paperback editions. Most have new introductions, complete bibliographies and two or more books in one volume!

More info at StarkHousePress.com.

CLICK TO MANAGE