9:05 a.m. From the rooftop terrace, you could hear all around the city the horns blasting, even from the ships in the Bosphorus. Down in the streets below, someone was playing “Taps” on a melancholy trumpet. And finally, the stirring, majestic sounds of the Turkish national anthem rippled like wind through proud flags in the cold November morning. Nearby, a few of my Turkish colleagues stood silently, with solemn, reflective faces.

The incessant fervor lasted a several minutes, but seemed longer, the great city – and the nation beyond – pausing as it does every year on this day at exactly this time – to remember the life and work of the founder of the republic, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, or “Father Turk.”

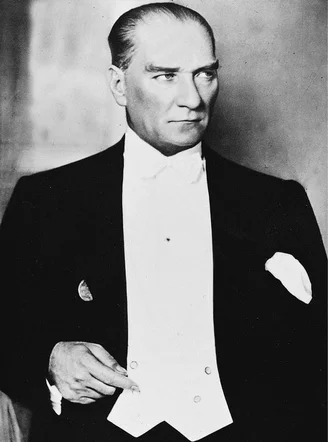

Ataturk! Photo: Public domain, via Wikimedia.

Having lived here for many years, I’ve long grown accustomed to this annual display of mourning and honoring the legacy of Ataturk. It was at this time: 9:05, on 10 November 1938, that the great leader passed on at the untimely age of 58.

As a yabancı, it is always an arresting event, even after so many years, to see and hear the nation stopping to collectively remember the passing of the man who many here feel, to paraphrase one historian, singularly picked up the exhausted Ottoman Turks and all but lifted them into the 20th Century. From the battered remains of a defeated empire, Ataturk envisioned and crafted a leaner, fitter republic, equipped and guided it into the modern age.

I made it a point of learning more about Ataturk upon my arrival in Turkey more than a decade ago. How could you not? More than 80 years after his death, his visage can still be seen everywhere, his portraits hang in nearly every establishment, and some youths even bear his signature or famous quote as tattoos on their arms. “Happy is the one who can say, ‘I am a Turk!’” is one of the most-oft recalled, underscoring the pride that Ataturk innately grasped, instilled and harnessed in his people.

Those who aren’t familiar with the late Mustafa Kemal, and who are interested in modern history, would find the story of his life well worth their time. In the first World War, he was a soldier, and though the Ottomans (who fought with Germany) eventually lost the war, Kemal was the only Ottoman general who never lost a battle. After the war, with the empire in ruins, the Bosphorus under the control of the victorious Allies, the lands of Anatolia themselves in danger of being split apart, it was Ataturk who reassembled the army from the ranks of the people. It was Ataturk who rallied this army to fight yet another war, this time a War of Independence, against the Western-backed Greeks. After winning this war, Ataturk forced the Allies to the negotiating table and re-established Turkish control of the Bosphorus.

By 1923, the empire was gone, as were the sultans and Caliphate that had ruled the country for centuries, and a new republic was born and, like his historical ancestor George Washington, the victorious general became the republic’s first president.

Like Washington, Ataturk in the years of his presidency sought to build and develop his young nation. He negotiated a series of peace agreements with Turkey’s neighbors, a far-reaching policy of “Peace in Turkey, Peace in the World,” that had its intended effect: ıt kept Turkey out of the second World War, which Ataturk had foreseen. Indeed, when one reflects on the current war to the north, Turkey’s role as mediator in the conflict traces its roots at least in part back to the policies of Ataturk.

This admittedly isolationist, but self-preserving policy allowed Turkey to focus on modernizing its industries, public infrastructure as well as its education system. For the first time, women were allowed to attend university, to work outside the home, to pursue careers. Furthermore, desiring to link his country with the West, Ataturk ordered the country to adopt the Latin alphabet, and called upon all citizens to learn this new alphabet in three months. Three months! All newspapers, books, etc, were essentially changed overnight.

The importance of Ataturk’s life and work, especially in terms of the future NATO alliance, was recognized long after his death. In a 25-year commemoration speech, then-President John F. Kennedy called Ataturk “one of the great men of the 20th Century:”

“It is to the credit of Ataturk and the Turkish People that a free Turkey grew out of a collapsing empire and that the new Turkey has proudly proclaimed and maintained its independence ever since. Certainly there is no more successful example of national self reliance then the birth of the Turkish republic and the profound changes initiated since then by Turkey and Ataturk.”

###

To be sure, not all of Ataturk’s reforms have aged well. For instance, his ban on the headscarf for women who wish to attend university or work in public jobs has since been lifted. Women can now choose to wear or not wear the headscarf and still attend university or hold public office.

In fact, one could even say the legacy of Ataturk has become in recent years somewhat divided (what has not become at least “somewhat divided” in this day and age?). The current administration in Turkey has been in power for nearly 20 years, and its leader, President Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan, is seeking yet another term as president. How and why, critics ask, can one party hold power for so long in a so-called democracy?

The answer, some would say, lies in arguably unintended consequences of the reforms undertaken by Ataturk. That for decades, traditional, conservative Muslims felt persecuted, unwanted, sidelined in favor of their more “progressive, modern” colleagues. Imagine being a young Muslim woman and having to take off your headscarf (hide your beliefs) to attend your classes? Or not being offered a position solely based on your beliefs? For his many supporters, especially in the more conservative inlands of Central and Eastern Anatolia, Erdoğan and his AK Party remain popular and valued because they are seen as having restored and safeguarded Muslim traditions, after being treated (in their eyes) as second-class citizens in their own country for so long.

(Others would say that it was not animosity towards religion per se that was at the root of Ataturk’s great reforms, but rather against the Ottomans and their leadership, which he felt was responsible for the decline of the empire and Turkey having fallen behind the West, of having become “the sick man of Europe.”)

I offer the above not as a criticism of Ataturk, but rather as a different perspective, especially for those outside of Turkey and who know little about the country’s modern history and present-day situation. Yes, inflation is above 80 percent – rent and food prices, energy costs, in fact everything – is expensive. The country houses countless refugees, from Syria, Afghanistan, and now Ukraine and Russia. There is a general feeling of uncertainty, of what next?

Which is perhaps what gave such resonance to the chilly morning air this past Thursday morning, when I witnessed and heard so many, a nation so to speak, stopping its routine to pause and reflect, wanting to remember. What were they remembering? Greatness? Or perhaps it was the stability, the reassurance, that remembrance of great events and great people bring.

###

And why did I stop and reflect? Was it some kind of veiled response to the mid-term U.S. elections? Some oblique commentary on the murky, divided state of affairs today, here and in much of the West? A muted word of caution on the rise of fascist forces in the East?

Was it some cry for unity, for clarity in today’s world, a world that some describe as in “permacrisis,” besieged by pandemic, by war, by inflation, by threats both real and perceived? Is there something in the story of Ataturk and his nation that we can all benefit from hearing?

Perhaps I was just moved by the sights and sounds of 9:05 a.m., by the majestic tribute to a remarkable man. After all, my wife is Turkish, and our son is Turkish-American. Would such a union have been possible without the legacy of Ataturk? Do I not also owe a debt of gratitude?

Perhaps it is important for me to remember that much of the best we have in this world, the world we have inherited, is the direct result of remarkable people. The ground we stand on was ploughed, and the grain raised from it, so to speak, by firm, strong and sure hands. We need to remember them. “The biggest battle is the war against ignorance,” as Ataturk himself said.

Thankfully we do still have a world about us, and surely we still possess remarkable people. I hope so: for then, now and always, we need them.

###

James Tressler, a former Lost Coast resident, is a writer and teacher living in Istanbul.

CLICK TO MANAGE