Photo: Tressler.

###

When we moved into our new apartment this summer, it needed an extensive renovation. The workers were there all day for a couple weeks. With typical Turkish hospitality, my mother-in-law would make them lunch and offer tea. One afternoon, we were all sitting in the newly remodeled dining room, having lahmacun, when one of the workers and I, for some odd reason, found ourselves in a debate about Russia and the ongoing war to the north.

In the midst of the argument, the worker insisted adamantly that America was finished, that Russia would win the war against its neighbor Ukraine. I objected, and pointed out the string of losses and setbacks that the Russians had already incurred. Of course, politics can spoil the appetite, and seeing the bewildered looks on everyone else’s faces at the table, we both swallowed our nationalism and went on with the lunch.

Later, the incident stuck with me. Since the war began last winter, Turkey has officially been a neutral mediator in the conflict. Readers may even recall a trip I made last spring to Dolmabahçe Palace here in Istanbul, where Russian and Ukraine delegations met briefly for the first of several failed peace talks. Since then, other meetings were more fruitful: for example, the agreement that allows grain and wheat from Ukraine to be shipped through the Bosphorus, and on the other side, some Russian yachts have reportedly been anchored here, safe from seizure. The Turkish government has also publicly denounced the recent annexations of Ukraine provinces by the the Russians in controversial referendums.

Yet as my run-in with the construction worker seemed to indicate, one cannot always regulate the feelings of the people, to paraphrase a scene from “Casablanca.” Surely, that worker was not alone in his opinion. Are some Turks rooting for a Russian victory? I guess the answer is, it’s complicated.

###

From the 19th Century Crimean War, which pitted the Russian Empire against the Ottomans (with the British and French), through to the present-day war, Turkey and its giant neighbor to the north have had a complicated relationship, at times at odds, other times benevolent, generally mixed. The same could be said of its relationship with its Nato allies, I suppose. And why not? Both the East and West see Turkey as a valuable strategic partner, particularly for its access to the Dardenelles and the Mediterranean, and as a power player in the region. Think also about how the U.S relied on Incirlik Air Base during the Afghanistan and Iraq Wars.

Turkey, perhaps because of its location, has always been sought as a partner and ally, pulled back and forth. The West employs diplomatic measures, reminding Turkey of its role as a NATO ally, and the EU for years has frustratingly dangled the possibility of EU membership in exchange for cooperation – this came into play especially during the Syrian Civil War, when a desperate Europe pleaded with Turkey to take ownership of the refugee crisis – to which an annoyed President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan refused, declaring that his country alone would not be the world’s warehouse for refugees. And so on … there are many twists and turns in the story of the East and West and Turkey. Let’s focus on the more immediate.

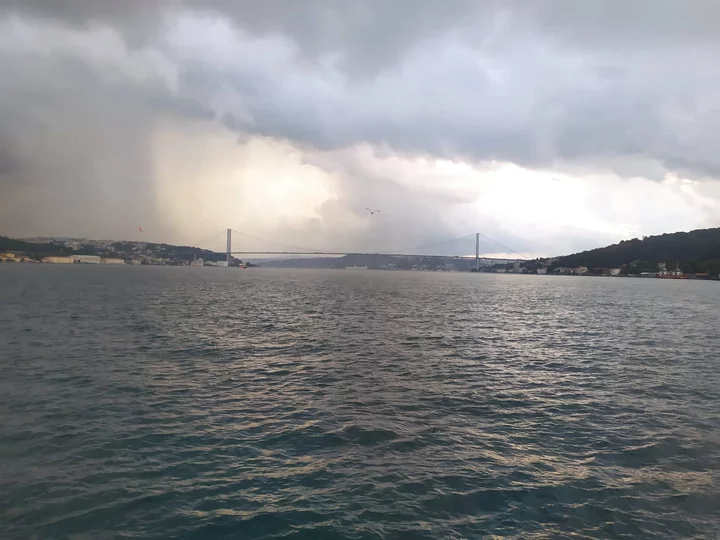

Here in Istanbul, not a day passes that I don’t look out at the Bosphorus and see all the vessels, big and small, bearing names from near and far, passing north and south, a reminder that this slender waterway is one of the world’s busiest, important not only for commerce, but also in that it connects not only people but cultures.

Since the war began last winter, we have read daily news reports about Turkey’s oft-stated role as mediator. Erdoğan met with Ukraine President Zelensky in Lviv in August, and reportedly was set to meet with Russian President Putin in the Kazakhstan capital Astana this past week to discuss, among other things, the importance of economic ties, and he has spoken to both men over the phone on several occasions.

While all of these gestures, and others, give evidence of Turkey’s commitment to a neutral stance, again one has to wonder how much public policy differs from the person on the street. Isn’t that always the case? For most, honor will not feed an empty stomach, nor will it pay the bills. With Turkey’s economic situation, already bad before the war, and not appearing to be improving, you wonder if at some point these pressures will force Turkey to choose with its stomach rather than its head, to put it crudely.

You may have read of the crippling inflation we are facing here in Turkey – 83 percent according to a BBC article just a week ago (To which my Turkish friends and colleagues scoffed, waving their hands dismissively. “It’s a lot higher than that! Much more!”). I can personally attest that even basic necessities like bread and milk cost five times what they cost just a few years ago. One of my teacher friends, an American, related going to a restaurant in his Taksim neighborhood one day to see the prices had gone up, and then going back a few days later, only to find the prices had gone up yet again. The cost of a monthly metro pass, which millions here in the city rely on to commute, went up this year from roughly 200 lira to more than 600 lira.

The causes of this hyperinflation trace back to well before the war, when Turkey borrowed billions internationally to fund a series of mega-projects like the Marmaray, the subway that runs beneath the Bosphorus and connects Europe and Asia, as well as a third span bridge, an undersea car tunnel and the new international airport, said to already be the busiest in Europe. Well, of course this money had to be paid back, but when Turkey’s economy stalled in recent years, and its currency sank (it’s now about 18-1 down against the dollar), and its political situation grew unstable with a failed coup attempt in 2016, foreign investors lost some confidence. All of these pre-War factors have, in one way or another, contributed to the soaring rise in costs.

At the start of this year Turkey was emerging from the pandemic and hoping that a return of tourism would put the economy back on course. Then, unhappily, the war came along.

###

Which brings us to the Ukrainians and Russians here. In 2019, some 7 million Russians visited the country, whereas this year the number fell to a little over 2 million so far. Just for comparison, a “record” number of Americans visited Turkey this past year – 477,000, which illustrates that even in a bad year, the Russian tourists far outnumber those coming from the U.S. Of course, distance accounts for some of that. For many Russians, Turkey is an ideal summer destination, with Istanbul and the calming waters of the Med to the south only a few hours’ flight away.

I can attest to that. Every summer my wife and I (and now our son) fly down to the south coast, where her family has a house in Anamur, and on every flight the plane is filled with Russians. Most are bound for Alanya and Antalya, popular coastal towns where even the signs and menus are in Russian as well as Turkish. So for many years, the Turkish tradespeople have welcomed the Russians, as well as Ukrainians, since they are a vital part of the tourism economy.

In the wake of Putin’s recent call for the draft, we have read of many fleeing Russia. According to news reports, more than a few have chosen to flock to the south coast, and are buying up properties, which suggest they are choosing to stay for the long term. At any rate, they appear invested.

Meanwhile, here in Istanbul, merchants and vendors who depend on tourism say the war has negatively affected their businesses. In a September story on Euronews, the owner of a Bosphorus fish restaurant claimed that half of his customers are Russian tourists. With sanctions imposed by the West, many customers find that their credit cards don’t work. Imagine you are a restaurant owner, already dealing with rising costs (rent, utilities) as well as many locals (like my wife and myself) choosing to stay home. How would you feel if your best customers aren’t able to pay?

“I am not happy, and my guests are not happy,” the fish restaurant owner told Euronews, an online news outlet, last month. “For Russian people, it’s difficult.”

One can suppose it’s not much easier for him as well. As I said, locals like my wife and I would love to show our support for these restaurants, but the fact is that with these prices, we simply cannot afford to eat out very often. It has become almost a luxury. A meal that cost 200 lira a couple years ago will run over a thousand now – for the same meal! You just feel ripped off, but you realize that it’s not anyone’s fault, everybody is just trying to get by.

Anyway, if you reflect on the dependence these locals have on Russian tourism, then perhaps it’s easier to understand why some, like my construction worker, get defensive when the subject of the war is brought up, and even more so if it is suggested that Russia may well be losing. After all, maybe they don’t agree with the invasion, but they do feel a vested interest in Russia’s long-term well-being as it is inexorably tied to their own, at least in terms of everyday living. As I said, for some here, perhaps ideals or “the good fight” are luxuries they feel they can ill-afford.

###

A few years ago, I wrote a story about Trotsky’s house on one of the Prince Islands here in Istanbul. The house was up for sale, so that story provided the opportunity for me to explore the 1917 Revolution and its aftermath, of the White Russians who fled to Istanbul. To this day, in some parts of the city, vestiges of the White Russians remain, such as an old Russian Orthodox church in the neighborhood of Karaköy.

Last spring, I visited both the Ukraine and Russian embassies, just to get a glimpse of some of today’s refugees. Some were going to stay in Turkey, while others were anxiously hoping to get travel visas to Europe or the States. Seeing these people standing patiently, some with children, in queues, clasping bags and paperwork, was like déjà vu, reminding me of the numerous Syrian families I’d seen camped out on the streets of my neighborhood at the height of that conflict. Most of them have gone – either enculturated (many opened businesses, their children enrolled in schools), or else continued on to points West). Nowadays, one doesn’t hear much about the Syrians. Does that mean the conflict is over, or that the world’s interest just moved on to the latest crisis du jour? Or to other refugees: At this point, there are a reported 145,000 Ukrainians in Turkey, while the number of Russians who have fled their country since the war began is estimated at 200,000 – although it is difficult to find an official number on how many have come to Turkey.

Personally, I hope that one day, the war and all its attendant misfortunes and tragedies will end soon, and these stories entered into the long book of history on Turk-Russian relations, along with those of their long-vanished ancestors. But whatever happens, Turkey and Russia, as well as Ukraine, will continue to co-exist, to depend on each other economically, well into the future. For that reason, one understands why the country is hoping to keep its neutral role, mediating a hopefully peaceful end soon. Some would suggest that it’s a disingenuous route at best, dangerous at worst, as JFK warned in his inauguration speech at the height of the Cold War, “Those who foolishly sought power by riding the back of the tiger ended up inside.”

But what can you say? Given the situation, perhaps striking the middle ground is the only course the Turks have, and they must make it work, with help from its Western allies. Their livelihood in a sense depends on them resolving this bloody dispute between two very valued neighbors. I, and most others, have always seen Turkey as a bridge between East and West. If that is the case, then it is a bridge that’s strength is being sorely tested. Since we are ending with metaphors, let us hope that it is made of sterner stuff than the Crimea bridge that went up in smoke last week.

###

James Tressler, a former Lost Coast resident, is a writer and teacher living in Istanbul.

CLICK TO MANAGE