“It’s

less work, it’s

less effort, it’s

less painful,

to

reject reality than to reject a belief you’re

emotionally invested in.”

— Franklin Veaux on Quora, h/t Dave Fitzgerald

###

I see where our last ex-president says that, next news conference, he’ll provide irrefutable proof that he was cheated out of a second term. Again. The proof is always just around the corner, any day now, yet somehow it never quite materializes. So how his followers take this? Do they say, “Hey, the guy’s obviously lying, I’ll never vote for him again”? Nope, quite the opposite: they double down. According to CBS last week, “Trump far and away leads the GOP field among voters who place top importance on a candidate being ‘honest and trustworthy.’” So: why do people, something approaching 80 million Americans, believe him? It’s called cognitive dissonance.

The phrase seems to have originated in a 1956 book, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World, by Leon Festinger and others. They studied a small religious group in Chicago, “The Seekers,” whose guru, housewife and automatic writing practitioner Dorothy Martin, predicted a huge flood for the night of December 21, 1954, which would wipe out much of North America. (She based her knowledge on messages received from the planet Clarion.) When nothing happened, many of the group members dug in, coming up with (implausible) rationales for the non-event. Somehow they were able to keep two contradictory events in their minds simultaneously, that (a) the flood was definitely coming and (b) it didn’t come.

Festinger wrote later, in an article for Scientific American, “…cognitive dissonance…centers around the idea that if a person knows various things that are not psychologically consistent with one another, he will, in a variety of ways, try to make them more consistent.” Wikipedia’s entry on cognitive dissonance sums up Festinger’s idea: “Coping with the nuances of contradictory ideas or experiences is mentally stressful. It requires energy and effort to sit with those seemingly opposite things that all seem true. Festinger argued that some people would inevitably resolve the dissonance by blindly believing whatever they wanted to believe.”

Trump’s true believers have plenty of predecessors, going way beyond that small Chicago group. Today’s Seventh Day Adventists and Jehovah’s Witnesses have roots in the “Millerites” of the 1840s. William Miller, a Baptist lay preacher, predicted Jesus’ Second Coming would occur “sometime between March 21, 1843 and March 21, 1844.” (He based his prophecy on the Book of Daniel.) Following the latter date, he announced Jesus’ return would take place, definitely, on October 22, 1844. When that date came and went, the majority of Millerites — we’re talking tens of thousands of believers all across the United States, and in the U.K. and Australia, many of whom had sold their property in anticipation of The End — stuck to their guns! New dates for the Second Coming were proposed, or perhaps Jesus had returned, but was keeping quiet about it, or it’s going to happen any second now. Miller himself wrote, “The time, as I have calculated it, is now filled up; and I expect every moment to see the Savior descend from heaven. I have now nothing to look for but this glorious hope.” (Seventh Day Adventists claim that October 22, 1844 was only the start of the process of atonement/cleansing, which is ongoing.)

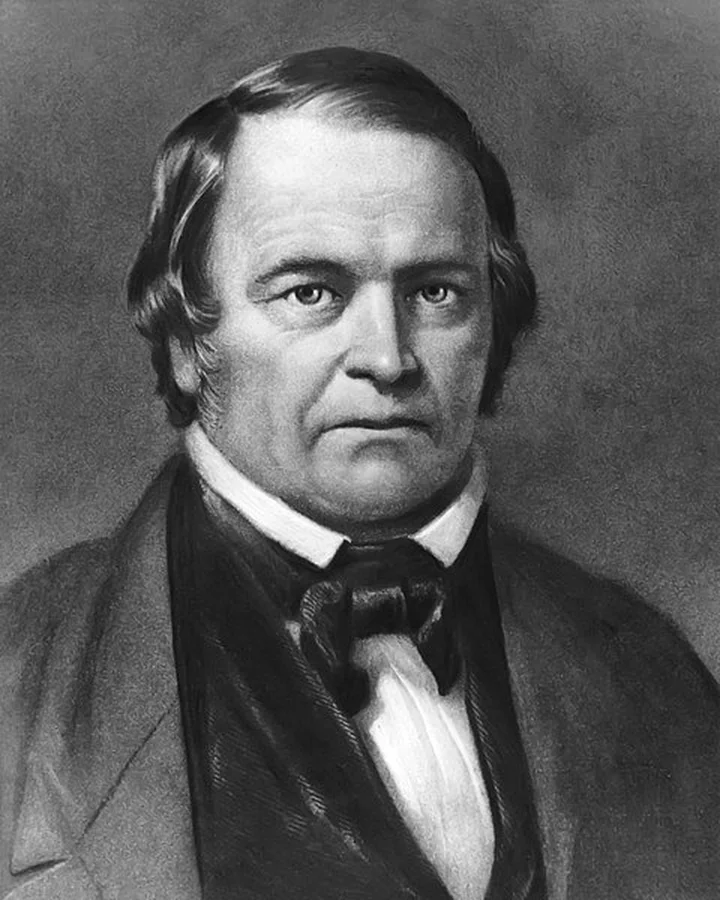

William Miller, 1982-1849. (Unknown artist, Wikimedia, public domain)

For Millerites, Seekers and Trumpists, it’s easier and less stressful to continue to believe what part of you knows to be false than to face reality: cognitive dissonance in action. They can take heart from Charlie Brown. Okay, so when Charlie went to kick the football, Lucy snatched it away, every time. But next time, it’ll be different. Only believe.

CLICK TO MANAGE