Dr. Emmett Chase (left) and Dr. Eva Smith both started working at the K’ima:w Medical Center in 1997. | Photos via UCLA’s Fielding School of Public Health.

###

Last month, the Medical Board of California accused Dr. Eva Smith, a primary care physician and longtime medical director at Hoopa’s K’ima:w Medical Center, of unprofessional conduct.

In a 13-page filing, the Medical Board’s interim executive director, Reji Varghese, says Smith is guilty of negligence and/or incompetence for prescribing “dangerous drugs” such as morphine, oxycodone and diazepam in “extremely high amounts” without documenting patient history, physical exams, treatment plans, toxicology testing or her rationale for handing out such high doses. He is asking the Attorney General’s Office to revoke her physician’s and surgeon’s certificate.

The allegations against Dr. Smith come less than two years after her husband, former K’ima:w CEO and fellow primary care physician Dr. Emmett Chase, faced similar accusations from the state medical board. Specifically, he was charged with prescribing “dangerous drugs” such as fentanyl, Norco and Dilaudid in “extremely high amounts” without meaningful patient assessments, documentation or rationale.

Chase is not currently practicing at K’ima:w. Last year he entered into a settlement agreement with the state, which took effect this past March. Per the terms of a disciplinary order, Chase was placed on a three-year probation during which he’s prohibited from prescribing, dispensing or possessing any controlled substances besides buprenorphine, which is used to treat opioid use disorder.

He was also ordered to enroll in an educational course in proper prescribing practices and one in medical record keeping, and he must reimburse the state $19,226.25 for the cost of its investigation and enforcement.

Smith, meanwhile, remains employed at K’ima:w while she’s being investigated. She has stepped away from her role as medical director but remains a practicing primary care physician with full prescribing privileges. Numerous attempts to reach Smith and Chase for comment on this story, both by phone and email, went unreturned.

Other people had plenty to say. One person we interviewed for this story was Marcellene Norton, an 83-year-old retiree and former member of the K’ima:w Medical Center’s governing board who has been concerned for years about the proliferation of opioids coming from K’ima:w. Four others were former employees of the clinic, including licensed nurses, a physician assistant and a doctor. In a series of interviews, they told the Outpost that the state’s allegations against Chase and Smith barely scratch the surface of the unethical conduct they have witnessed.

Each characterized the clinic as a full blown pill mill where, for more than two decades, Dr. Chase and Dr. Smith doled out breathtaking amounts of prescription opioids, indirectly supplying a thriving black market in diverted pills while contributing to widespread and devastating addiction across the Hoopa Valley and beyond.

They also said that Dr. Smith, in particular, failed to keep up with her paperwork, regularly getting so far behind on patient records that residents routinely ran out of their medications, missed much-needed referrals to specialists or went without care altogether.

On the surface, these allegations may sound incongruous or unlikely given the credentials and accolades that have been accumulated by Chase and Smith.

Chase, a graduate of Stanford Medical School and UCLA School of Public Health, grew up in the Hoopa Valley and is a member of the tribe. Formerly the medical director for the American Indian Free Clinic, he served as president of the Association of American Indian Physicians and as director of the AIDS Program of the Indian Health Service. In 2014, he was inducted into the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health’s Hall of Fame.

Smith, a member of the Shinnecock Indian Nation in what’s now New York, received the California Medical Association’s 2013 Frederick K.M. Plessner Memorial Award, which honors the member who “best exemplifies the practice and ethics of a rural practitioner.” She is certified in addiction medicine through the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and she, too, has been inducted into the UCLA Fielding School of Public Health’s Hall of Fame.

And yet the former board member and medical professionals we interviewed say this married duo has used their positions of authority irresponsibly. And three of the four former employees we interviewed said they were let go from the clinic based on trumped up allegations after they tried to blow the whistle on unethical things they’d seen.

The K’ima:w Medical Center in Hoopa. | File photo.

###

The former clinic employees we interviewed each asked for anonymity to protect themselves from personal and professional repercussions. We’ll refer to them by aliases, indicated with an asterisk on first reference.

Sharon*, a licensed nurse, said the rampant overprescribing at K’ima:w was enabled in part through the clinic’s organizational structure, which she said was rife with conflicts of interest.

Formerly known as Hoopa Health Association, the clinic is the tribe’s official health care entity, and it has been in operation since 1974. It’s financed by Indian Health Services (IHS), along with state funding and various grants, and is supervised by the K’ima:w governing board, whose members are selected and overseen by the tribal council.

Sharon and several of the other people we spoke with said that addiction became so commonplace in the Hoopa Valley that members of both the K’ima:w governing board and the tribal council got hooked on pills supplied by the clinic’s own pharmacy, which made them disinclined to crack down on prescribing practices.

Beyond that, Sharon said there were conflicts within the chain of command of the clinic’s medical staff. Not only were the CEO and medical director married to each other, with a man named Dr. Stephen Stake serving as chief operating officer, but according to Sharon, Smith also had compromised supervisory responsibilities with Dr. Dagim Taddesse, who was hired as the clinic’s pharmacy director in 2017.

Generally speaking, pharmacy directors are supposed to act as a check on the power of prescribing physicians. They have the authority to refuse to fill a prescription if they believe it’s too strong or otherwise unwarranted. (Most medical clinics don’t have their own in-house pharmacy, but K’ima:w is an exception.)

While working as pharmacy director, Dr. Taddesse was pursuing his advanced practice license, which would give him prescribing privileges of his own while making him more valuable and employable. (He has since acquired that license.) In order to obtain the certification, Taddesse needed to log a certain number of clinic hours under the supervision of a prescribing physician, and Dr. Smith agreed to fill that role. In Sharon’s view, this turned the clinic’s chain of command into a circle.

“It was [a case of] ‘You scratch my back, I’ll scratch your back,’” she said. “There is no accountability in this circle, and that all goes back up to K’ima:w’s board, who just turned a blind [eye] to this whole thing.”

Dr. Kevin Lang*, a physician who worked at the clinic for several years, agreed that the dynamic was improper.

“It set up a situation, to me, where there was a huge conflict of interest,” he said. “[Taddesse] was supposed to be monitoring [Chase and Smith’s] opioid prescribing practices, but he was also dependent on them — one, for his salary but, two, for his ability to get this advanced pharmacist license.”

‘Way too many opioids’

As a physician’s assistant, Sarah* saw many of Dr. Smith’s patients, and when Smith went on vacation, Sarah was responsible for filling their prescriptions. Smith only took vacations about once a year, but after a couple of years of filling in, Sarah began to grasp the scale of her boss’s prescribing practices and grew very concerned.

“The recommendation is that people are on a certain number of morphine equivalents, like 90 morphine equivalents,” Sarah said. (CDC guidelines used to say that doctors should “avoid increasing dosage” to 90 morphine milligram equivalents or more per day or to “carefully justify” such a decision. Updated guidelines say “clinicians should prescribe the lowest effective dosage.”) Smith regularly went way beyond that mark, Sarah said. “The majority of people there were on 120 up to over 200 morphine equivalents [per day],” she said.

“Dr. Chase was even worse,” Sarah added, “because he would put people [who were] super young [on opioids].”

Sarah kept seeing patients who were on “way too many opioids,” she said. “It just keeps happening. … I think the last straw was the pregnant mom who was coming for a refill for Tramadol [a synthetic opioid with high risk for addiction and dependence]. She was 37. It was for back pain. She was started on it for the first time during her pregnancy.”

The pregnant woman complained that her fetus wasn’t gaining weight, Sarah said, “and I’m thinking, ‘Well, of course not! He’s sleeping all day because you’re on Tramadol!’ And why would you put a pregnant person on that? You just never would. You just wouldn’t. You wouldn’t give a pregnant mom a narcotic that might affect the pregnancy.”

Sarah said the woman came in after the baby was born. She was still nursing the infant and wanted a refill. Sarah said she refused, though she found that such refusals can lead to ugly confrontations.

“I had a patient corner me in a room [and say], ‘I’m not leaving here until I get my pills,” Sarah recalled.

According to Dr. Lang, a fundamental problem was the lack of oversight at virtually every level. He told the Outpost that the K’ima:w governing board knew about the overprescribing problem.

“In fact, I presented to the board some numbers that I had gotten from the CURES database,” he said, referring to the Controlled Substance Utilization Review and Evaluation System, a database maintained by the State of California for tracking controlled substance prescriptions across the state.

“And they really didn’t seem concerned,” he said. “Or they they were concerned but didn’t do anything about it, and it just seemed like they were all in on it and knew about it but for whatever reason didn’t want to do anything about it.”

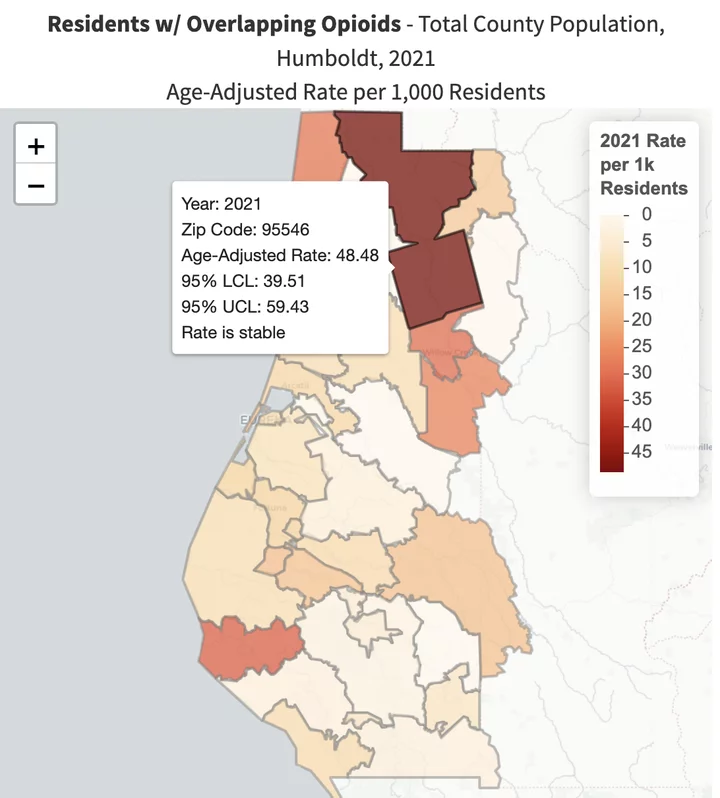

The CURES data tells quite a story. The 95546 area code, which encompasses the Hoopa Valley Reservation and remote communities such as Weitchpec and Martins Ferry, has a population of less than 3,500 people and just one pharmacy: the one at K’ima:w.

Throughout the 2010s, the 95546 area code had more than four times the statewide rate of residents on super-high doses of opioids (90 or more milligram morphine equivalents, or MMEs, per day).

After peaking in 2011, use of prescription opioids in the United States has declined by 64 percent due to a variety of factors, including prescriber and physician education, changes to prescribing guidelines and quotas imposed on drug makers by the Drug Enforcement Administration.

That trend has held true in the Hoopa Valley, as well, but as of 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, the rate of residents on 90 MMEs or more per day remains nearly triple the statewide rate. See the graph below.

Another set of data reveals the scope of opioid inundation in the Hoopa Valley. From 2010 through 2018, residents in the 95546 area code had more than six times the statewide rate for MMEs per person per year, peaking in 2015 at an age-adjusted rate of 4,317 MMEs, which was 7.4 times the state average.

As you can see in the graph below (as with the one above), the volume of opioids being prescribed has declined dramatically in recent years, especially in the Hoopa Valley, though the rate in that zip code remains nearly four times the state’s.

Marilyn Powell, a Hoopa Tribal member and public health nurse who formerly served on the Ki’ma:w Medical Center’s governing board, told the Outpost that she, for one, is reluctant to place too much blame on Chase and Smith because prescribers and physicians across the country were misled by pharmaceutical reps.

“I worked in hospitals, and we were told that giving morphine and [other opioids] to people with acute surgery, they’d be fine,” she said. “Come to find out, we were misinformed — I [was] along with all the providers. Wool was pulled over our eyes by all the pharmaceuticals. … There are so many reasons and avenues why we’re in the boat we’re in. It’s a multifaceted problem.”

In 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, the 95546 area code had the county’s highest rate of overlapping opioid and benzodiazepine prescriptions, which nearly doubles the risk of overdose. | Source: CDPH.

###

Dr. Dagim Taddesse, K’ima:w’s pharmacy director and the only person currently employed at the clinic who we managed to get a hold of, said the clinic has discontinued a lot of medications and reduced the number of pills being prescribed by more than two-thirds during the six years he’s been employed there.

“We were able to decrease more than half a million pills of narcotics,” he said in a phone interview Wednesday. “So that was a huge decrease.”

Taddesse said that after he was hired, he presented updated CDC prescribing guidelines to the community, the K’ima:w board and providers. He declined to speak about the allegations pending against Dr. Smith, and he did not respond to a follow-up email asking about the alleged conflict of interest between the two of them during his pursuit of an advanced pharmacist license.

Poor record-keeping and diversion

Marcelline Norton, the retired board member, said both Chase and Smith were chronically late in filling out patient charts and notes from visits.

“That’s crucial,” she said. “We have a policy of 72 hours to complete the chart notes. But Dr. Smith at one point was over 1,000 patient charts behind. How can a person remember the diagnosis with each patient?”

Norton said this had an impact on both patient care and the clinic’s bottom line.

”There were patients who probably needed to be referred to specialists and some who maybe needed prescriptions renewed. And K’ima:w was losing money because if charts aren’t completed, they can’t bill for money,” Norton said.

Sharon said the missing paperwork had serious impacts on patient health.

“The patients were being neglected because they weren’t able to get their routine medications, even people that had cardiac issues or blood pressure issues — they were being denied their medications,” she said. “That’s pretty much a slow death. If you have renal issues or heart issues and you go without your meds for a month, you’re basically slowly killing yourself.”

She and Anna*, another licensed nurse who used to work at K’ima:w, remember the crowds of patients who would show up to the clinic regularly asking to have their expired prescriptions renewed, mostly opioid prescriptions.

“A lot of these patients have been out of their medications for days,” Sharon said. “Our biggest concern: that [delay] just put that individual into withdrawal.”

Local residents showed up daily, with as many as 50 or more people filling the lobby at closing time most Fridays, Sharon said.

“And they absolutely would not leave the building until they got [their refills]. They’d be there until, like, 7:30, 8 o’clock … and Dr. Smith would be in the back, frantically writing these scripts. These people had run out and were in withdrawal. Almost every single day.”

Anna said that not everyone getting pills was actually taking them. More than a third of residents in Hoopa live below the poverty line, and for some, opioid pills offered a lucrative source of income.

“Some of these narcotics are just synthetic heroin,” Anna said. “So [Smith] would write the scripts, and Partnership [HealthPlan] or Medi-Cal would pay for it. So here’s people getting, you know, 280 [or] 360 pain pills a month, and they sell it.”

Some of the stronger opioids, such as Percocet, Vicodin and Norco, sell for a dollar per milligram, Anna said, and they were often prescribed in pills of 50 or 100 milligrams apiece.

“That’s a hundred dollars per pill … ,” Anna said. “I can name three families — I will not name them to you — but I mean, I personally know three families that lived off their prescriptions. They would sell them for $10 a pill. One [family] had six children. And it was all profit”

Dr. Lang said diversion of pills happened “all the time” in Hoopa, and not all the diverted pills were sold. Some just got stashed away for later use, by the patient or any family member in any sort of pain.

“I think the prescribing practices of Smith and Chase just made opioids so common that that no one even thought twice about giving it to a kid for whatever pain they had … ,” Lang said. “They were prescribing opioids to patients without an appropriate diagnosis or physical exam to support it,” he added, referencing the state medical board’s accusations. “So it doesn’t surprise me that anybody could get opioids for whatever condition.”

When we noted that this sounds like the classic definition of a pill mill, Dr. Lang replied, “Oh, absolutely. Absolutely.”

Sarah agreed. “Everybody gets it for any kind of pain,” she said. “Everybody has it around at home.”

Predictably, as opioid use increased, so, too, did addiction and overdose deaths, and the community has taken steps to address the problem, calling in former Humboldt County Health Officer Dr. Donald Baird for community meetings, for example.

Norton remembers seeing a dramatic increase in opioid-related overdose deaths in the Hoopa Valley in the last seven or eight years.

”I think that was the beginning of when fentanyl was coming in,” she said, adding that when patients could no longer get their prescriptions filled, they sometimes turned to heroin. “Now, I understand, fentanyl is the choice of street drug.”

Asked if the community is still seeing a lot of overdose deaths, Norton said yes. “I talked with the ambulance director a couple months ago. He has given a report to the tribal council [showing] that we’re seeing more and more calls for young people overdosing.”

A call to the chair of the K’ima:w Medical Center Governing Board Chair Angela Jarnaghan would not go through. (We got a Verizon message saying the number “has calling restrictions that have prevented the completion of your call.” Texts would likewise not go through.)

Hoopa Tribal Chair Joe Davis declined to comment for this story.

Reporting and retaliation

Anna said that after she took a stand against some of what she’d seen, she was subjected to retaliation in the workplace.

“They would sabotage my computer, steal my mouse, take my lunch and throw it in the trash.”

Who was the “they”?

“The MAs [medical assistants], the nurses, Dr. Smith. It’s a pack mentality,” she said.

Anna and Sharon said they ran afoul of three influential MAs in other ways — namely, by refusing to sign off on forms granting them authority to distribute narcotic medications to patients.

“They’re not allowed to do controlled substances, and they’re not allowed to give any drug that has to be mixed,” Anna said. “There’s things that are illegal for them to give, and they wanted me to sign off and say that it was okay, and I wouldn’t do it. That’s my license. … Their thing is, ‘We don’t have to abide by the State of California’s rules because we’re tribal.’ That’s not true. My license doesn’t have anything to do with the tribe. Nobody’s does. It has to do with the state of California, not the tribe.”

“MAs are not allowed under their scope [of practice] to distribute narcotics,” Sharon confirmed. “And MAs were distributing narcs on the daily. …. They were going into the closet and taking them out, and the medical director was allowing them to do it.”

Anna said she was eventually fired, “and they interrupted a doctor-assist procedure to do it,” she said. “They refused to let me chart what I had done. Then I was escorted out of the building by security. They had gathered my things for me.”

The only reasons she was given for her termination were that she was “not a team player” and was “no longer needed,” she said.

Sharon was also fired — by Chase personally, she said — but not before she and Anna tried to blow the whistle on the unethical behaviors they’d witnessed and experienced, including the rampant overprescribing of opioids and the unauthorized distribution of narcotics by medical assistants.

They submitted information to the Office of the Inspector General, the Indian Health Service, the California Department of Consumer Affairs, the California State Board of Pharmacy and the Joint Commission, a nonprofit health care accreditation organization. (Sharon forwarded some of her correspondence with these organizations.)

“Chase fired me while I was on medical leave,” she said, adding that he falsely accused her of verbally harassing coworkers. “He actually fired me because he knew that information had been gathered and submitted.”

Sharon said she never got one reply from any of the organizations she contacted. Someone from the Board of Pharmacy came for a half-day inspection and found discrepancies between K’ima:w’s records and the CURES database but wound up chalking the mismatch up to a computer glitch, she said.

Marcellene Norton, the 83-year-old former board member, believes she was also the victim of retaliation when the tribal council removed from her first term on the board.

“They didn’t give me a reason, but I believe it was because myself and other board members were trying to bring about improvement,” she said. “There were recommendations that a wife should not be overseen by her husband, and we were working on that. We were also working on the [CURES] narcotic report.”

Sarah said that while she was still employed at K’ima:w, she filed a complaint to the Board of Pharmacy, which was discovered by her bosses when the agency sent a receipt for the complaint to an administration email address at K’ima:w.

“And then a month later, all of a sudden [I was told], ‘Oh, we’re having issues with’ — I don’t know what they said — ‘You’re walking away too abruptly from the nurse’s station.’ That’s what they said. ‘It’s making the staff feel uncomfortable.’ … It was all B.S. I knew what they were doing. … They’d write you up so they’d have a paper trail and a cause not to renew your contract.”

Sure enough, when her contract expired a couple of years ago, Sarah was told that it would not be renewed.

Dr. Lang said he noticed this trend, and his fellow doctors were not immune. “A lot of good physicians have left the clinic for different reasons and a common thread was complaints which I thought were often frivolous, made by staff members against certain nurses or physicians,” he said. “And they were eventually let go. And it just so happens that that these were people who either filed complaints or had concerns about the opioid prescribing practices.

“A medical assistant or a nurse would make a complaint about a provider or a nurse and they were let go,” Lang continued. “And I think that’s why they’ve been able to get away with this for so long. They prefer to hire locums, or temporary physicians and providers. When [those providers] figure out what’s going on, they’re let go for whatever reason.”

Lang said he’s really hoping that the investigation into Chase leads to some fundamental changes at the clinic.

“I know that if you look at the numbers, prescriptions of opioids are coming down,” he said. “I think, once the CURES system was put in place, they had a way of tracking individual providers and their prescription practices, and I think they were forced to do that, which is a good thing. But it doesn’t undo the harm that has been done over the past 20 years.”

On Saturday morning, K’ima:w Behavioral Health is hosting a “Walk Against Drugs” in Hoopa, with lunch and guest speakers afterward. A related statement posted to the clinic’s website says Dr. Taddesse and the rest of K’ima:w’s medical team have taken “every step” to decrease opioid prescriptions in the Hoopa Valley. He’s quoted as follows:

“We use every encounter with a patient to educate about the harmful outcomes of long-term use of opioids. It can lead to dependence and, when misused, opioid pain relievers can lead to overdose incidents and deaths.”

###

DOCUMENTS:

CLICK TO MANAGE