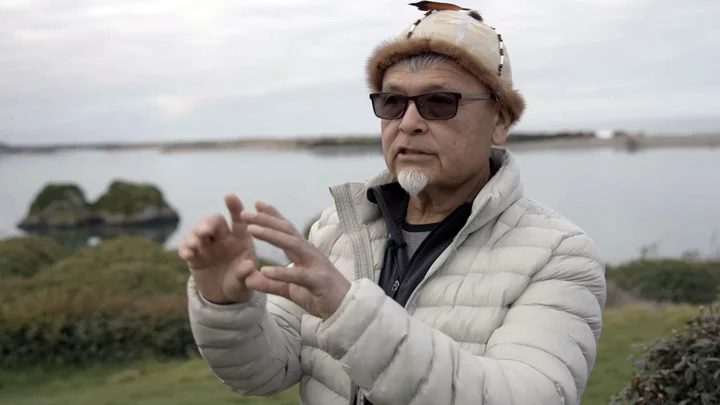

Loren Bommelyn is a Tolowa language keeper who spearheaded its transition from an “oral tradition” to a “written tradition.” | Photo courtesy of Cal Poly Humboldt and the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation.

Each language has a worldview a way of interpreting reality, Loren Me’-lash-ne Bommelyn says. For more than a century, society considered his uncivilized.

Bommelyn grew up in a “mixed language dynamic.” His mother, aunts and uncles were part of a generation who largely responded to their Tolowa-speaking elders in English. Those elders had survived religious proselytization and boarding school. Their parents and grandparents lived through massacres and forced relocation to reservations.

Some protected their children by deliberately not teaching them Tolowa, Bommelyn said, while others decided “I am the way I am and I talk the way I talk.”

“I remember seeing a movie — I don’t remember the name of it now. It was a Western and the characters were just out on the prairie shooting Indians,” Bommelyn told the Wild Rivers Outpost on Wednesday. “He gets shot and the dust flies. I go, ‘Yay!’ Dad goes, ‘What are you doing? Did you know that guy? That’s your uncle.’ I said, ‘What?’ He said, ‘What are you?’ I go, I’m an Indian.’ He said, ‘Who was he?’ And I go, ‘He was an Indian.’ A light came on in my head. I realized I’m a member of the bad guy population and it completely re-wrote my script.”

Bommelyn, who has spearheaded the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation’s efforts to save its language from extinction, is one of 10 language keepers featured in the documentary ‘A’-t’i Xwee-ghayt-nish: Still, We Live On. The film was created in partnership with the tribe and Cal Poly Humboldt.

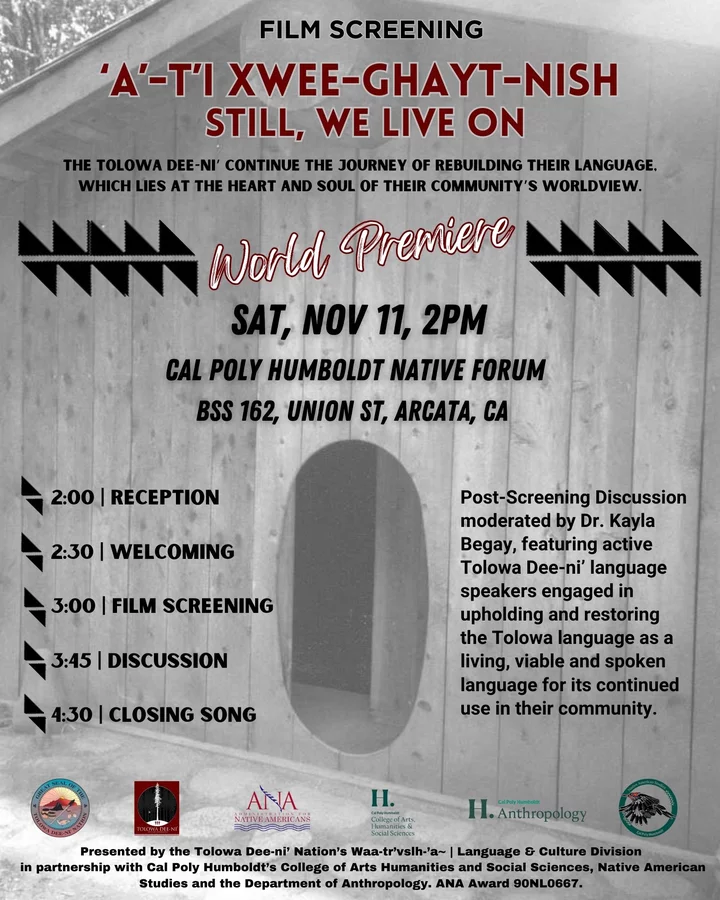

Film professor Dave Jannetta is the director. The producers are Cal Poly Film Lecturer Nicola Waugh and Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation Language and Culture Division Manager Marva Sii~xuutesna Jones.

The documentary will be screened at 2 p.m. Nov. 11 at Cal Poly Humboldt’s Native American Forum in Arcata. The screening will include a reception featuring traditional Tolowa foods and a panel discussion with Bommelyn and other voices from the film.

Still, We Live On will also be screened at 4:30 p.m. Nov. 18 at Xaa-wan’-k’wvt Hall Community Center, 101 Indian Court Road in Smith River. That event will also include a reception and discussion featuring the Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation’s language keepers.

According to Loren Bommelyn, former Tolowa Dee-ni’ Nation culture department director Pyuwa Bommelyn wrote a grant to document how their language evolved from being a “spoken tradition” to being a “written tradition.”

Loren Bommelyn said his people just began developing Tolowa as a written language in 1968 using a list of about 30 people who were born between 1868 and 1930.

“We worked with those people a lot capturing ethnographic information, village locations, villages that people descended from and just as much vocabulary that I could collect from them,” Bommelyn said. “We were pretty fortunate in that they remained in-situ — (despite) how rough it was and how the genocide occurred and the dysphoria that occurred as well, these folks were a handful who ended up continuing to live in Del Norte County.”

During the 1850s, the Tolowa people endured massacres by white settlers. In his book, An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, Benjamin Madley writes that the 1853 massacre near Yontocket Slough south of Smith River “may rank among the most lethal of all massacres in U.S. history.”

Despite the official tally from white sources estimating that roughly 150 people were massacred, Tolowa sources state that as many as 600 people may have lost their lives at Yontocket, Madley writes.

According to Bommelyn, the people he and others interviewed were “L1 speakers” — Tolowa was their first language.

“The community at that time was somewhat close. People knew each other and a lot of us were interrelated,” he said, adding that in the 1960s a lot of tribes had lost their language because their last-known speaker had died. “We were kind of fortunate. The four tribes in our area who have documented their language starting in the same period, they still had in-situ L1 speakers in their communities.”

Bommelyn said as a kid, his mother would take him to visit one of those elders, Amelia Brown, who lived to be 110 years old.

“I was so inquisitive and I wanted to know these things,” Bommelyn said. “I would come up with scenarios and questions and she would answer them for me.”

Another elder, Sam Lopez Sr., carried the law and protocols for the Tolowa Dee-ni’s ceremonies. Lopez passed that baton to Bommelyn when he died.

According to Bommelyn, Lopez, who had become a Christian, was alive when Congress enacted the American Indian Religious Freedom Act in 1978. As moderator of those ceremonies, Lopez spoke on the Tolowa Dee-ni’s behalf.

“I remember being in Klamath, at the Klamath Salmon Festival when it was young, and he said, ‘Well, sisters and brothers we’re here today to do some ceremony dancing.’ And he said, ‘I have read that Bible from end to end and what I come to know today is the God they talk about in the Bible is the same God of my ancestors.’ And he goes, ‘Let’s Dance!’,” Bommelyn told the Outpost. “We never got to capture all of this stuff in the story, but this is how the language was working in all of that.”

Filmmakers began working on Still, We Live On over the summer of 2022, Waugh said. In addition to screening the film locally, she and Jannetta plan to enter the documentary into film festivals, including those focusing on indigenous causes, across North America.

There’s also plans to show the documentary on PBS following the festival run, Waugh told the Outpost.

“Our entire goal was to make a film for the community,” she said. “But it has broad enough appeal to exist outside of that. If we get a good reception in Del Norte and Humboldt it’ll make the tribe extremely happy.”

Bommelyn said documenting the ongoing revitalization of his language is important because a lot of Tolowa people “can find no economic reason to speak Tolowa,” so they question the importance of learning it.

Then there are others who are ignorant of the language itself. Learning Tolowa is viewing the Tolowa world through its own lens, he said.

Up until now, Bommelyn said, Tolowa religion and spirituality had been seen through an English framework. He said he sometimes gets jealous of those who speak their original language.

“We had to speak a colonizer’s language and wonder about our world,” Bommelyn said. “That’s the ultimate gift to the new generation — to know who you are in a deeper way, a clearer way.”

CLICK TO MANAGE