Eric Matilton of Hoopa poses with his nieces in September of 2022. | Photo submitted by his parents.

###

UPDATE, DEC. 1:

###

Clyde and Jeanine Matilton stood outside the entrance to St. Joseph Hospital in Eureka today, having just left the bedside of their son, 38-year-old Eric Matilton, who is on life support in the Intensive Care Unit.

His injuries have been declared non-survivable, they said. He will likely die within days or even hours, and they say their only hope now — the only thing that might bring them some peace of mind in the midst of tragedy — is if some of his organs can be salvaged from his body to save the lives of others.

They were in the Bay Area on the afternoon of Saturday, Nov. 18, when they got a call from a sheriff’s deputy saying he had bad news: Their son Eric had been found unresponsive, hanging from his neck in his cell the previous day.

Eric Matilton is a registered organ donor, and personnel from Donor Network West, a nonprofit organ procurement and tissue recovery organization, have flown into Humboldt County to help arrange and facilitate multiple donations.

However, over the past 11 days, while Matilton lay unconscious, his condition slowly deteriorating in the ICU, Humboldt County Sheriff-Coroner William Honsal has denied all requests to allow the donations to proceed. In emails and other written communication to employees of Donor Network West — as well as the chairman of the Hoopa Valley Tribe, of which the Matiltons are members — Honsal has said that because Eric Matilton suffered his fatal injuries while in law enforcement custody, departmental protocol mandates that a full criminal investigation be completed, including an autopsy, and therefore organ donation is not an option.

Clyde and Jeanine Matilton have tried numerous times to get Honsal to explain this policy, to meet them in person or even on the phone and help them understand why their son’s wishes would be denied, but he has declined, saying there’s nothing to discuss. Protocol is protocol.

“Eric wanted to donate his organs,” Clyde said. “We want to honor that, and we still do. But we’re running out of time here and we’re just being stonewalled. The sheriff has absolutely refused to talk about it.”

Robynn Van Patten, chief legal and administrative officer and executive vice president of Donor Network West, said her organization has also been struggling to get Honsal to communicate. She believes his office policy is both unjust and contrary to accepted protocols across the state and beyond.

“Organ donation and autopsy are not mutually exclusive,” Van Patten said when reached by phone this afternoon. “We routinely work with medical examiners and sheriffs because we’re in many counties. And what we do is we cooperate.”

If a criminal investigation needs to be conducted, it can co-exist with organ donation. “We can preserve evidence, take samples, do biopsies. We do that anyway to determine if the organs can be transplanted into a human … ,” Van Patten said. “The issue is that this sheriff is relying on a protocol … that says anytime someone passes away in custody they have to do a full autopsy. But he has not had any discussion with us about the fact that both can occur.”

That fact is even spelled out in state law. California Health & Safety Code 7151.20 says that a county coroner can allow organ donations from people who died “under circumstances requiring an inquest by the coroner.” If the coroner wants to withhold one or more organs from donation for any reason, they (or their designee) must show up to the autopsy. And if they deny organ removal, they can explain their reasoning in an investigative report or explain it to “the qualified organ procurement organization,” which, in this case, would be Donor Network West.

“The sheriff or coroner can cooperate with us,” Van Patten said. “We have mutual objectives: to preserve the integrity of forensic investigation while saving these lives.”

Like Eric Matilton’s parents, she’s been frustrated by the lack of communication from Honsal. “He has not had any discussion with us,” she said. “His belief is just, ‘Hey, that’s our protocol.’ I think it’s a mistaken belief. If he’d have a real conversation — he won’t — there’s a good chance he’d change his mind and have his pathologist say, ‘We can do the donation.’ Instead he just says [conversation is] not necessary. ‘We have a protocol.’ It’s crazy.”

The Outpost emailed Honsal earlier today but did not receive a reply before publication time. The department lost its public information officer weeks ago, and Honsal himself has not responded to Outpost emails for months.

Eric Matilton had multiple run-ins with the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office over the years, including a 2016 standoff in which he allegedly fired a weapon in the direction of deputies, one of whom shot back. His most recent arrest was on Nov. 3.

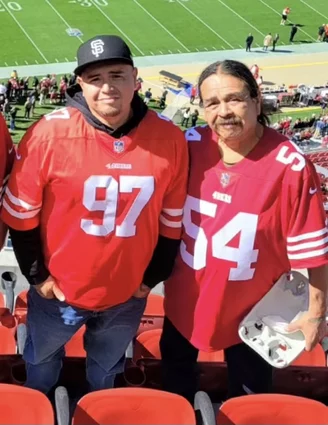

Eric Matilton (left) with his father, Clyde Matilton, at a San Francisco 49ers game last October. | Submitted.

But his parents say their son was a lot more than his criminal record might suggest.

“I want people to know about my son,” said his mom, Jeanine, outside the hospital this morning. Choking up, she continued. “I mean, he was a dad, he was an uncle, he was a brother, he was a husband. He was a person. I don’t want to take that away from him.”

A member of the Hoopa Valley Tribe born and raised on the reservation, Eric Matilton has three children, ages 7, 14 and 18, and a fiancee who may as well be his wife, since they’d been together for so long, Jeanine said.

Jeanine and Clyde don’t suspect any foul play in their son’s pending death. They understand that he hanged himself in jail. But they want to honor his wishes, and they want his body to save the lives of others.

“He was the one who wanted to donate,” Jeanine said.

Clyde doesn’t understand why they’ve gotten the runaround. Hoopa Valley Tribal Chairman Joe Davis reached out to Sheriff Honsal on their behalf, he said, but Honsal again said that protocol precludes organ donation in this case, and further conversation would be pointless.

The Matiltons’ requests to at least speak with him have been denied “over and over and over again,” Clyde said. “Then they [deputies] cite, ‘Oh, we had a shooting, we’re short staffed. It was the holidays.’ But now we’re into Wednesday and it’s still just ‘No.’” Clyde shook his head. “That’s a pretty hard ‘no’ because there are four people that are waiting for his organs that could die.”

Van Patten said Eric Matilton’s body parts could save the lives of as many as seven other people. Donor Network West has identified four potential recipients who are matches for his blood type, and with his two kidneys, heart, liver, corneas and skin tissues possibly available for donation, more organ recipients are possible.

The Matiltons said they can’t say where all of his organs would end up, though they’ve been told that his heart would be sent to someone in Los Angeles.

“In this case, here’s the deal,” Van Patten said. “This is a relatively young and healthy man who had, certainly, a tragedy befall him. I don’t know that the family thinks there’s foul play. They just want to know why. They just want the sheriff to talk to them. For our part, look, we’ve expended a lot of resources on this. This would bring a lot of peace to the family. It’s a healing opportunity that they want and that [Eric] himself wanted.”

Van Patten said it’s possible that Sheriff Honsal or one of his designees could find a valid reason to deny the organ donation request. If the office sent someone with medical knowledge into the operating room and identified an organ or two that they needed to withhold for an investigation, that would be within their rights. But to make that determination from afar strikes her as unjust, and possibly tragic.

While Honsal has been “very unresponsive,” Van Patten said she and her staff have managed to get hold of deputies lower on the chain of command for brief discussions. “But at no point have any of them provided a copy of that [department] policy or explained which part is incompatible for donation. It’s like there’s a foregone conclusion that [the organ donation request] will be denied because it’s their policy.”

Donor Network West is considering filing for injunctive relief or an order to show cause, but timing is an issue. There’s not much of it left before the case becomes moot. Throughout the course of her career, she said, only one other coroner — also from a rural county — denied her organization’s request for an organ donation. But in that case, the coroner at least sent someone to the operating room who denied the request onsite.

“Many, many counties are able to do both an autopsy and provide evidence — and do organ donation,” Van Patten said.

Outside the hospital, Clyde said he understands that his son’s fate is now sealed, but others aren’t.

“I believe in the [donor] system, especially now,” he said. “It’s so hard to lose a son. It is. And we’ve got the ability to help some other family that won’t have to go through this. … That’s about the only good that’s gonna come out of it for me, you know. My son’s dead.”

Van Patten made virtually the same point.

“We can’t get away from the human impact of this,” she said. “This one family would have some peace and healing from a tragic thing that occurred, but also this [situation] is important globally because if that’s the [Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office] policy — or if that’s how it’s being interpreted — think about all the lives that will be lost over time.”

The Humboldt County Correctional Facility. | Photo by Andrew Goff.

CLICK TO MANAGE