“…astronomers, physicists and engineers…are simply unaware of the fact that the success of any SETI [Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence] effort is not a matter of physical laws and engineering capabilities but essentially a matter of biological and sociological factors.”

— Ernst Mayer, evolutionary biologist

###

Some while back, I noticed a tendency for different groups of scientists to have wildly differing views on the likelihood of the existence of intelligent extraterrestrial life. In a nutshell, it seemed that biologists and their ilk were pretty pessimistic about there being intelligent aliens out there—at least in our own galaxy, beyond which it’s just too far to worry about. (Having a conversation when there are millions of years between sending and receiving messages seems kinda moot.) Meanwhile, physicists and engineers tend to be optimistic.

The biology argument goes: To get from amino acids (which we know are out there) to a living cell requires an insane number of improbable steps, then to go from a cell to intelligence needs a zillion more fluky mutations. Here on Earth it took nearly four billion years, and our planet is particularly favorable in which life can emerge and evolve, with our benign orbit, a single moon, and a remarkably stable sun.

OTOH, say the physics types, look at the numbers! There are maybe 400 billion stars in the Milky Way, with about as many planets, according to data from the Kepler Space Telescope. Chance alone means there are some on which intelligent life has arisen, amirite?

Stars and more stars! M11, aka “Wild Duck Cluster” from Big Lagoon recently. Light left there about the time the wheel was invented, 4200 BC. (Barry Evans)

###

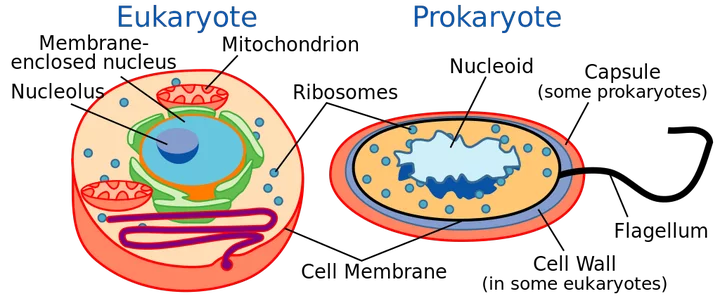

I’m not, of course, the first to notice this dichotomy, which was articulated in a 1995 debate between astrophysicist Carl Sagan and evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayer in 1995, about two years after NASA canceled its $100 million funding of the SETI organization by congressional mandate. Mayer opened the “debate” (which actually took place in back-to-back issues of the Planetary Society’s Bioastronomy News) complaining that physicists assumed that evolution was deterministic: Once life got started, it will naturally evolve towards intelligence. Countering this teleological view, Mayer insisted that “evolution never moves on a straight line towards an objective,” but is much more complex process. Backing this view, he pointed out that nearly half the time in which Earth supported life, that life consisted of simple prokaryotes; and that just one of Earth’s 50 billion or so species had achieved high intelligence. (Dolphins and chimps are intelligent, but they don’t build radio telescopes.) Conclusion: Intelligence such as ours is highly arbitrary. (Note that Mayer, like Sagan, had no problem with simple life, in the form of blue-green algae or something similar, existing all over our galaxy in suitable environments.)

Sagan replied in the next issue, that life doesn’t have to follow the same evolutionary pathway as the one that produced us. “There may be many different evolutionary pathways, each unlikely, but the sum of the number of pathways to intelligence may nevertheless be quite substantial,” he wrote. From the Copernican Principle (i.e. we’re average), “…it would be odd to exclude the possibility of intelligent life on the possible planets of the 400 billion stars in the Milky Way.” Given our ignorance, Sagan concluded, we should “try and actually find out the answer.”

For about half the time there’s been life on Earth, it was in the form of prokayotes, single-celled organisms that lack nuclei. This suggests that evolution is a very hit-and-miss, undirected, process. It took the appearance of eukaryote cells with nuclei, some two billion years ago, that life as we know it really took off. (National Institutes for Health, public domain

What neither of them addressed head-on was the likelihood, in my mind, that any technologically advanced civilization will inevitably invent the means to destroy itself. In our case, we have many possibilities for the suicide of our species: nuclear weapons, global warming, overpopulation, diminishing sperm count, ocean acidification, lethal viruses…The idea that we’ll be around in hundreds of years, enough time to connect with any extraterrestrials (who may well face similar perils) seems pretty remote. For what it’s worth, skeptic Michael Shermer came up with an average of 420 years for the lifetime of a civilization here on Earth, based on 60 historic societies. That’s a pretty small window of opportunity in the grand scheme of things.

My money’s on Mayer. We’re probably alone. I wish it were otherwise.

CLICK TO MANAGE