“Some

say there is nothing finer on this dark earth than an army of horses,

or an army of men, or an army of ships. But I say that your lover is

the most beautiful sight of all.”

— Sappho

###

After announcing a few weeks back, with the confidence born of writing nearly 500 of these weekly rants (this is #499), that the Greek poet Sappho wasn’t gay, I had my doubts and delved deeper. Well okay, it isn’t like we know she didn’t have a thing for the sistahs back on the island of Lesbos some 2600 years ago. In the only complete poem we have of hers, Ode to Aphrodite, she writes of her galpal who’s about to marry a man “equal to a god.” Sappho is already missing “the sweetness of your speech … if I gaze, my voice does not obey … sweat trickles, I tremble and shake and I am pale, paler than grass. I feel as though death is near.”

My heart beats a little faster just reading this! Sappho’s reputation as a poet was well established in ancient Greece; when the Alexandrians assembled their list of the top Nine Lyric Poets she was included, while her name was added to the Nine Greek Muses of antiquity, becoming the Tenth Muse. Just as Homer was sometimes simply referred to as The Poet, Sappho was given the sobriquet The Poetess.

Incidentally, while others described her as “violet-hair, pure and honey-smiling,” she says of herself that she was short, dark and unattractive. (Sounds like false modesty.)

Sappho, shown holding an early lyre, c. 470 BC. ArchaiOptix, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.

There’s another female poet of old whom I’ve been reading up on lately, dubbed “the Shakespeare of Sumerian literature.” Enheduanna, who lived about 1700 years before Sappho, was the daughter of King Sargon of Akkad. She has the singular distinction of being the first author to sign their text. She also — perhaps for the first time — described her process of writing: “The moon goddess comes at night and inspires my creativity,” she said. Archeologists only “discovered” Enheduanna — or at least linked 37 previously-found baked-clay tablets with an inscribed “Disk of Enheduanna” and several seals — in the last few decades. Since then, she’s become a model for feminism, although there’s some evidence that, in her role as high priestess, she was used by her father, who was in the process of creating a great empire by unifying south and central Mesopotamia. We have three hymns by Enheduanna, all dedicated to the goddess Inanna.

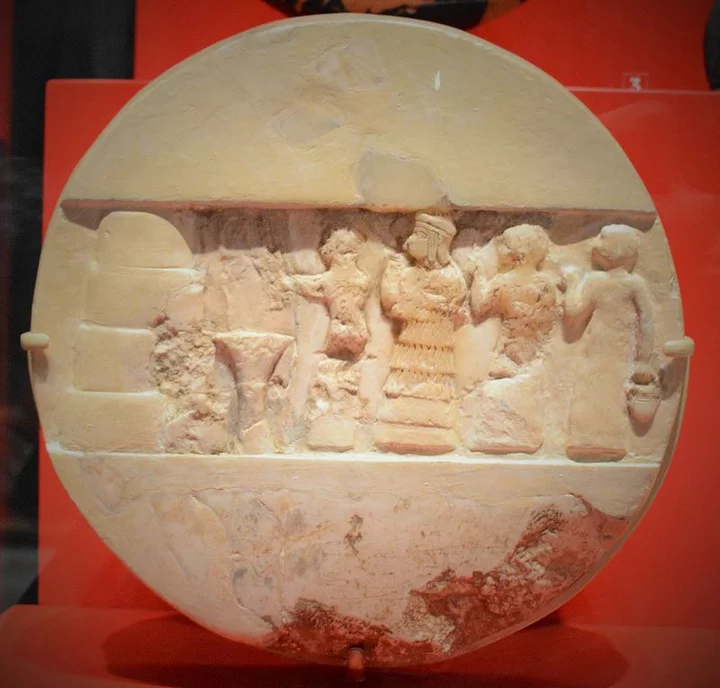

“The Disk of Enheduanna” showing the high priestess standing in worship. Mefman00, via Wikimedia. Creative Commons license.

Other ancient woman writers include Korinna of Boeotia, notorious for beating the Greek poet Pindar in poetry competitions five times; Nossis of Locri (just 12 of her epigrams survive); Theophila, compared to Sappho, but nothing of hers survives. And barely a handful more, unfortunately, a paltry collection compared to the surviving works of male authors. Whether there were other great female poets of old, but whose work disappeared or was destroyed, at this point it’s fair to say that we’ll never know.

CLICK TO MANAGE