Eureka City Schools District office. | All photos contributed by district staff.

###

Eureka City Schools is doing away with traditional grading in favor of a new educational system that will allow students to advance at their own pace.

Over the next four years, administrators aim to improve student success by replacing the district’s traditional, one-size-fits-all learning model with a “competency-based framework” that empowers students to take ownership of their education.

However, some educators worry that the new system will overwhelm teachers. In an interview with the Outpost, a representative of the Eureka Teachers Association said many of their questions about the new system have gone unanswered.

In a personalized, competency-based learning (PCBL) system — similar to student-centered or performance-based education — students are referred to as “learners” while teachers serve as “learning guides” or “learning facilitators” to encourage collaboration over traditional directive teaching. The goal is to help students develop a deeper knowledge of a subject through real-world, hands-on projects.

“In PCBL, relevance and purpose are much clearer to the learner and to the teacher,” Nanette Voss, a teacher on special assignment for Eureka City Schools, told the Outpost. “Teachers can plan projects around standards that demonstrate skills, course knowledge, and are relevant to students and their interests. In a traditional system, the ‘why’ of learning is often lost in the details, in the memorizing, in the repetition, in the foundational skills needed to actually do the higher-order thinking.”

Often, Voss said, students are too bogged down by “busy work” and other low-order thinking tasks (basic recall and comprehension, like memorizing facts or defining terms) to achieve high-order thinking skills that require deeper analysis and critical thinking.

“For example, a science teacher might have students read and take notes on vocabulary and processes, [take] a quiz on vocabulary and processes, and then they just repeat that same formula of teaching and learning with the next chapter,” Voss explained. “In PCBL … the recall activities would be complete when the learner demonstrates an understanding of those concepts, and then they would get to apply it to a bigger, more challenging task, like a lab or an experiment.”

“Students will feel more accomplished and confident with their learning, and like they actually did something, rather than just regurgitate facts and vocabulary,” she added.

There are no letter grades or percentage points in PCLB. Instead of report cards, student success is measured through “learning progressions” and ranked on a four-point scoring scale. A score of 1-2 indicates that the student can understand basic knowledge of a subject, but they have not yet mastered the content. A score of 3 indicates proficiency, and a 4 demonstrates learning “above and beyond” proficiency.

Students “pass” when they meet a specific standard or learning target, and move on to the next content level, regardless of their age or grade level.

“They need to demonstrate mastery in a standard before moving on to the next one in that learning progression,” Voss said. “Knowledge is building one standard at a time. In a grade book, instead of keeping track of percentages of a task that a student has completed, they either meet the target or they don’t. … Teachers are still the final ‘judge’ of whether a target is met or not, but the student knows exactly what they need to do to get there.”

If a student doesn’t meet their target, they’re given more time and support to apply the standard. This allows the student to be “more connected to their own learning” and “assess themselves along their journey.”

District staff conducting a “learner listening session” at Zane Middle School.

Garett Montana, a Eureka High School teacher on special assignment leading the district’s “learner agency” development, emphasized the importance of shifting the student perspective from “time and the art of getting grades” to learning.

“When a unit of study is over, students are tested, and the class moves on,” Montana told the Outpost. “Students [who] learned the material to 60 percent or better pass. Inevitably, our learners have to answer for the holes in their learning, and for many, their progress comes to a point where they are struggling and lose confidence and interest in their schooling. [PCBL] is about meeting each learner where they are, giving them voice and choice, making the classroom relevant to their lives, and inspiring them to own their own learning.”

Under the current system, grades are often “blurred” by other factors (participation points, extra credit, etc.) that have nothing to do with the subject being studied. “The key idea is that a grade must reflect learning and learning only,” Montana said. “Students can earn ‘good’ grades without necessarily demonstrating true understanding. [PCBL] realigns grading to measure what matters most — actual learning and mastery.”

Still, Voss acknowledged that the shift away from a traditional report card is one of the “scariest” aspects of the transition for parents and caregivers.

“Even the teachers are worried,” Voss said. “The report card is way different, and many schools choose to keep the report cards PCBL 1-4 based, and once students hit graduation, they calculate their cumulative scores into a traditional GPA. Thankfully, other schools have taken this journey and have many tips and tricks on how to make the ‘report card’ transition smoother.”

One of the districts Eureka City Schools is looking to for guidance is the Lindsay Unified School District, a 4,200-student K-12 public school district nestled among the orange groves of Tulare County.

Eureka City Schools staff toured the Lindsay Unified School District in March 2025.

Lindsay Unified began its transition to a “learner-centered, performance-based” system in 2007 and fully implemented the program in 2013. The district has thrived under the performance-based system, hosting dozens of school tours each year and helping numerous districts across the country implement similar programs.

Last year, the Eureka City Schools Board of Trustees approved a three-year $245,000 contract for consultation services from Lindsay Educational Foundation for Learning to help the district develop its own PCBL program. More than 80 staff members have visited and toured Lindsay Unified’s eight schools to date, with more trips planned next year.

“The team returned energized and inspired by what they saw,” said Eureka City Schools Superintendent Gary Storts. “At the 30,000-foot level, our work is about intentionally redesigning an entire system so that every learner has the opportunity to thrive in a rapidly changing world. To guide this vision, [the district] has partnered with Lindsay Leads … to learn not only from their successes but also from the challenges they faced during their systematic redesign.”

How Lindsay Unified Created a ‘Brand-Smacking New’ Learning System

Twenty years ago, Lindsay Unified was plagued with “dismal” attendance, a 67 percent graduation rate, rampant drug use, gang culture, teen pregnancy and a “tremendous” amount of staff turnover, according to Barry Sommer, the district’s director of advancement.

“No one wanted to work at Lindsay,” Sommer told the Outpost during a recent phone interview. “I don’t think anyone wanted to learn at Lindsay either.”

After attending a conference hosted by educational researcher Robert Marzano in 2006, district leaders began meeting with staff, parents, unions and other community stakeholders to discuss the possibility of shifting to a performance-based learning system.

“As a cooperative, we decided that we were going to … eliminate [the current] model and develop something brand-smacking new,” Sommer said. “In that first year, we gathered lots of information about five different things: why we existed, how we can work together, what our guiding principles would look like, what the future would bring to education and what a graduate from Lindsay High School should be like. When we put it all together at the end of the year, and it became the Lindsay Unified Strategic Design.”

However, not everyone was on board. During the first five years of its transition to performance-based learning, the district lost nearly 20 percent of its staff.

“We were losing them anyway,” Sommer said. “They wanted to work in traditional systems, so it was a better fit for them to go work somewhere else. Nowadays, learning facilitators who come to work at Lindsay are coming because of the model … and we have very, very low staff turnover. … We’ve moved from being the laughing stock to being the model of competency-based education and personalized learning.”

The district has dozens of videos on its YouTube channel to give outsiders a peek into the average day of a Lindsay Unified student. The kids featured in the videos can be seen working one-on-one with a teacher or in small groups with other students, diligently typing away on an iPad.

“These are much more active learning environments,” Sommer said. “There is direct instruction when introducing a new concept or a new learning target. … Everybody has a device and it’s connected everywhere — at school and at home, at no cost to parents — so there is 24-hour learning going on. You can demonstrate your mastery of a learning target on Saturday, Sunday, or in the evening, if that’s your preference.”

Similar to the learning model Eureka City Schools is implementing, Lindsay’s students are assessed on a four-point rubric system. Asked whether the numbered system has made applying to college more difficult for graduates, Sommer said the numbers are easily translated into letter grades, with 4 being equivalent to an A, 3 to a B, etc.

“It was challenging at first, but now a lot of schools are doing it, so it’s not challenging at all,” he said. “We have the equivalent of a cheat sheet that goes along with our high school records that helps universities and colleges understand the equivalency of a 1-2-3-4 rubric. Three is basically equivalent to a B grade, and everyone basically has to have a B or better [to advance].”

Overall, the program has proven to be “incredibly successful,” Sommer said. The district’s graduation rate is now at 98 percent, and students are getting accepted into colleges and universities at a higher rate.

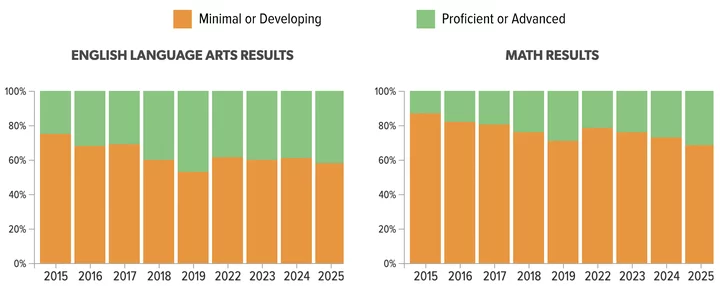

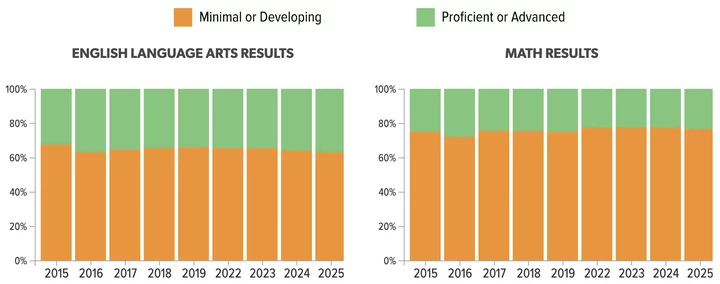

However, Lindsay Unified is still below the state standard for English and mathematics, according to the most recent California Assessment of Student Performance and Progress (CAASPP) scores. In 2025, 41.8 percent of the district’s students met or exceeded the state standard for English, and 31.74 percent met or exceeded state standards for math.

Lindsay Unified School District’s CAASPP scores for 2015-2025. | Graphic: EdSource

To put those numbers in perspective, the Eureka City School District’s CAASPP results for the same time period show 37.2 percent of students met or exceeded the state standard for English, and 23.7 percent of students met or exceeded standards for math.

Eureka City Schools CAASPP Scores for 2015-2025. | Graphic: EdSource

Asked whether state metrics provide an accurate representation of student achievement, Sommer emphasized that the CAASPP scores are grade-based and “not representative of the growth learners are achieving.”

“If you use comparative data for districts with demographics like ours, we are exceeding expectations,” he wrote in a follow-up email. “Even state standard testing has shown Lindsay making steady progress since the inception of the performance-based system. … Everyone who leaves Lindsay High School has demonstrated their competency in math, English, social science, history and in the pathway that they choose that’s best matched to their future preferences for employment.”

Above all, the district’s goal is to promote lifelong learning and instill values that transcend academics.

“We expect our graduates to be the kind of people you want as your neighbors or to marry your children,” Sommer said. “That means that they’re well-balanced, caring, compassionate people who are civic-minded and responsible global citizens and quality producers.”

‘In Theory, It Sounds Good’

If all goes according to plan, Eureka City Schools expects to have its PCBL system fully implemented at all eight of its schools by the start of the 2029-30 school year. Superintendent Storts offered assurance that the rollout will be carried out carefully, step by step.

“It needs to be incremental,” he said. “Much like a competency-based system inside the classroom, we can’t move on to the next phase until we’ve mastered the first phase. We have a group of teachers who are putting the playbook in place right now … and we will go from that to a pilot [project]. From there, we will reflect and adjust as needed. … We’re going to go slow to go fast. We’re going to commit to making sure that we get the prerequisite steps right, so that we don’t trip and fall.”

However, some teachers fear administrators are biting off more than they can chew. Matt Muldoon, a Eureka High School math teacher and bargaining chair of the Eureka Teachers Association (ETA), said he’s “hopeful that this is going to be a good thing,” but said a lot of his questions remain unanswered.

“I don’t think a lot of the questions of why we are doing this have really been answered — we’re just doing it,” Muldoon told the Outpost. “As the bargaining chair, I’m cautious about the changes in working conditions for the teachers because, from everything we’ve heard, it’s going to take a lot of work, a lot of planning and a lot of adjustments. And I have yet to see a plan from the district [explaining] how they’re going to provide the time for teachers to do the work to make the transition.”

For example, what will a PCBL classroom actually look like? How will instruction be affected under the new system? How will grading be affected? How much extra work will be put upon teachers under the new system? How will teachers manage a classroom of 30 kids who are moving through the material at different rates?

“When you talk about it in theory, it sounds good. When you think about how it’s going to work in a classroom, it sounds like an enormous amount of work,” Muldoon said. “Under our current model, if I give a test on chapter one, and I have 25 people pass and five people fail, we keep going to chapter two. Under [the PCBL] model, you can’t just move on. Am I then supposed to teach chapter two to the 25 kids who passed, and try to find the time to reteach five different kids who all have different holes in their chapter one knowledge?”

Eureka staff visiting Lindsay’s own Washington Elementary School.

Another question: How will the new program be funded?

Superintendent Storts was optimistic that the district would be able to track down grant funding to bring the vision to life. “I think there’s a general rule of thumb in school finance that you can do any one thing you want, but you cannot do everything you want — you’ve got to prioritize,” he said. “I don’t see this as having a much larger economic impact [than traditional learning].”

The Lindsay Educational Foundation for Learning receives funding from several big-shot donors, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, the Bush Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation of New York, among others. However, the website indicates that this funding is earmarked for scholarships and financial assistance for graduates and alumni, not district operations.

Asked how much Lindsay Unified paid to undergo its transition to performance-based learning, Sommer acknowledged that there were some “upfront costs” but said “it doesn’t cost any more money to do the [PCBL] system than it does to do a traditional system.” He directed further questions to Grant Schimelpfening, the district’s assistant superintendent of administrative services.

Reached for additional comment, Schimelpfening told the Outpost that it would be “difficult to assign a single cost figure” since the transition to the new system “occurred over many years and across every level of the organization.” The district received some grant funding from the U.S. Department of Education to “accelerate the transition,” but he did not provide any financial figures.

“While those grants provided important momentum, the work would have continued regardless, driven by the district’s long-term strategic focus on equity, personalization, and mastery-based learning,” he wrote via email. “The most significant investment was in building the capacity of our educators and leaders to operate within this learner-centered framework. … Our journey demonstrates that meaningful transformation comes from clarity of purpose and a mindset shift, not from extraordinary new funding.”

Lindsay Unified has contracted with more than two dozen schools across the country to set up their own performance-based learning systems. However, Schimelpfening declined to provide a cost estimate for Eureka City Schools’ transition, noting that the transition to a PCBL system “varies widely depending on factors such as district size, staffing structures, technology readiness, and the scope of implementation.”

“It’s important to emphasize that there really isn’t a meaningful way to assign a ‘price tag’ to Lindsay Unified’s shift to a performance-based system,” he continued. “In short, there is no single dollar amount that reflects the cost of becoming a performance-based system — because the transformation is about vision, alignment, and sustained focus, not a line-item expenditure.”

‘Change Can Be Uncomfortable’

As Eureka City Schools moves forward with its transition, Muldoon hopes administrators will provide more empirical data that illustrates the success of PCLB systems.

“It’s been very promotional,” he said. “I’m not gonna say it hasn’t been transparent, but it just seems like it’s been incomplete. The focus has been on trying to sell it to everybody without actually letting anybody really look at how it’s going to work in the classroom.”

Voss and Montana, the two teachers on special assignment we heard from earlier, emphasized that administrators are working to improve communication and build trust with district staff and the community.

“The staff is most certainly overwhelmed, and that overwhelm is totally understandable,” Voss said. “However, much of the change is just focusing on best practices of teaching that are pretty common in the world of education. So, as long as we let the teachers know that ‘the teaching is really the same; just use the best practices that you already have in your toolbox,’ they will be fine. The biggest shift instructionally is that teachers will need to shift how they plan from task/assessment-centered to skill/outcome-centered.”

Similarly, Montana acknowledged that “change can be uncomfortable,” but said this transition also presents an opportunity for the district to create a system that serves all students, “not just the ones who fit the mold.”

Speaking to Muldoon’s concerns, Superintendent Storts emphasized that the new learning system “is not a change for the sake of change,” it’s driven by the district’s “genuine desire to do better for our learners.”

“We want learners to take real ownership of their education, to see it as something they shape through their hard work, to be fully prepared for the world beyond graduation,” Storts said. “Change is never easy, but it is necessary, and our commitment to PCBL is about creating a system that has been shown to positively impact learners and give every child the opportunity to succeed.”

The district recently launched a monthly newsletter to keep parents and community members informed about the upcoming transition. You can read this month’s newsletter at this link.

CLICK TO MANAGE