Arcata Will Get Some More Bikeshare Stations; Nitrous Oxide Ordinance Passed

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 11:59 a.m. / Arcata

Tandem Mobility bicycles at the bikeshare station on Sunset Avenue in Arcata. By City of Arcata.

More bicycles!

Arcata’s city council voted unanimously last night to sponsor two more bikeshare stations on Cal Poly Humboldt’s campus.

There are currently eight Tandem Mobility stations scattered around Arcata in places that see a lot of foot traffic, each outfitted with a few heavy-duty commuter bikes complete with a basket. Cyclists can rent a bike for $1.50 for every 30 minutes of riding, though there are discounted yearly memberships. Riders can return the bike to any of the stations.

The city currently pays $72,000 a year for the stations. Cal Poly Humboldt provides $18,000 of that, and the remainder is funded through the Affordable Housing and Sustainable Communities (AHSC) grant and Bike and Pedestrian Local Transportation funds from the Humboldt County Association of Governments.

The $22,000 for the two new stations, located at Cal Poly Humboldt’s new Hinarr Hu Moulik dorms, will be paid by CPH. (The city is the party responsible for contracting with Tandem Mobility, so even though CPH is the entity kicking in the funds, the contract had to be updated through city council.)

The bikes were rented over 2,500 times last year by 1,618 riders, and city engineer Netra Khatri predicted an even more widespread adoption as time passes.

These stations won’t be the last. Khatri said there are plans to build three more: one in Sunny Brea, one by the Arcata Marsh, and one at the end of 11th Street near Greenview Market. He’s also trying to convince Eureka to build some within their city limits after the Bay Trail is complete, funded by the same AHSC grant — all part of a grand plan to enable people to cycle between the two cities and drop the bikes off as need be.

“It would be really nice to connect with Eureka too once that trail is open,” councilmember Sarah Schaefer said. “I’m really looking forward to that.”

Nitrous ban official

At the last city council meeting two weeks ago, a motion to adopt an ordinance to ban the sale of nitrous oxide passed 5-0, meaning it was on last night’s consent calendar. There was no conversation from the city council or from the public about the ordinance. The city council passed the consent calendar, so it’s official; including today, there are 30 days left until it’ll be illegal to sell nitrous oxide in Arcata, except for medical purposes or if it’s in a food product.

BOOKED

Today: 4 felonies, 9 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

1700 Mm96 E Hum 17.00 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

9943 Mm101 N Hum 99.40 (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

2080 Mm271 N Men 20.80 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 N / Sr299 W Us101 N Con (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

Us101 N (HM office): Trfc Collision-Unkn Inj

0 Sr299 (HM office): Road/Weather Conditions

Mm199 N Dn 33.40 (HM office): Road/Weather Conditions

ELSEWHERE

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 17th, 2026 – Frank Nelson

Governor’s Office: Governor, First Partner statement on passing of Reverend Jesse Jackson

County of Humboldt Meetings: Humboldt County Behavioral Health Board Meeting - Feb. 26, 2026

County of Humboldt Meetings: Humboldt County Behavioral Health Board Meeting - Feb. 26, 2026

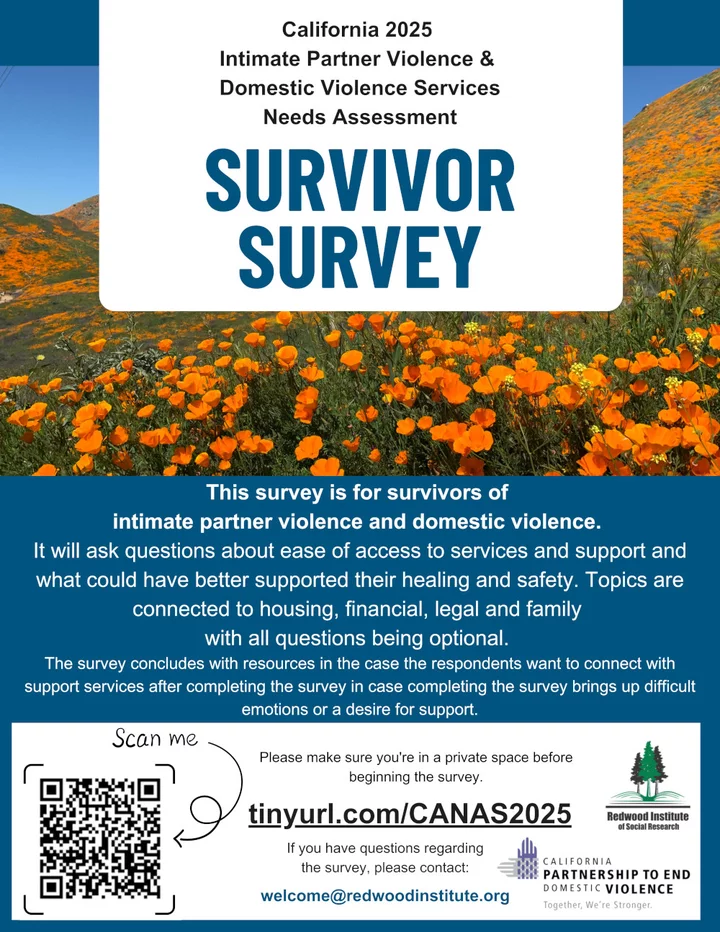

Are You a Victim of Domestic Violence? A Social Services Provider? Please Share Your Story With Researchers Who Are Hoping to Improve the Support System For People in That Situation

LoCO Staff / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 11:55 a.m. / Health Care

Press release from the Redwood Institute of Social Research:

Help Strengthen Domestic Violence Services Across California—Your Voice Matters

Redwood Institute of Social Research (RISR) is reaching out to ask for your support in an important statewide project. We are seeking input from advocates, service providers, and people with lived experience of domestic violence/ intimate partner violence. Your voice is essential in helping to identify current needs, challenges, and opportunities to improve domestic violence services across California.

Our team is conducting the California 2025 Intimate Partner Violence and Domestic Violence Services Needs Assessment for the California Partnership to End Domestic Violence (the Partnership). Your participation will have a direct impact on the training, resources, and support made available to advocates and service providers working to address intimate partner violence across the state. How can you help?

If you are a social service provider, please complete the Provider Survey (approximately 20 minutes) and/or share it with your colleagues

If you have lived experience with domestic violence, please complete the Survivor Survey (approximately 20 minutes), or share with survivors that you know and/or work with

Promote the project through social media and/or pass along to other organizations

Share your organization’s data. RISR is collecting information from organizations throughout California to gather current trends and demographics. This could include data from program evaluations and surveys you have completed in your own organization. If you have data to share please fill out this form and RISR will be in contact with you.

You can access resources to assist with outreach and communication efforts by visiting our online resource folder. Thank you for supporting this important initiative!

(PHOTOS) Largest-Ever Land Back Deal in California Returns 73 Square Miles on Lower Klamath to Yurok Tribe

LoCO Staff / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 11:02 a.m. / Nature , Tribes

The Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary. | Photo by Cindy Diaz.

###

The following press release was issued jointly by the Yurok Tribe, Western Rivers Conservancy and the California Wildlife Conservation Board:

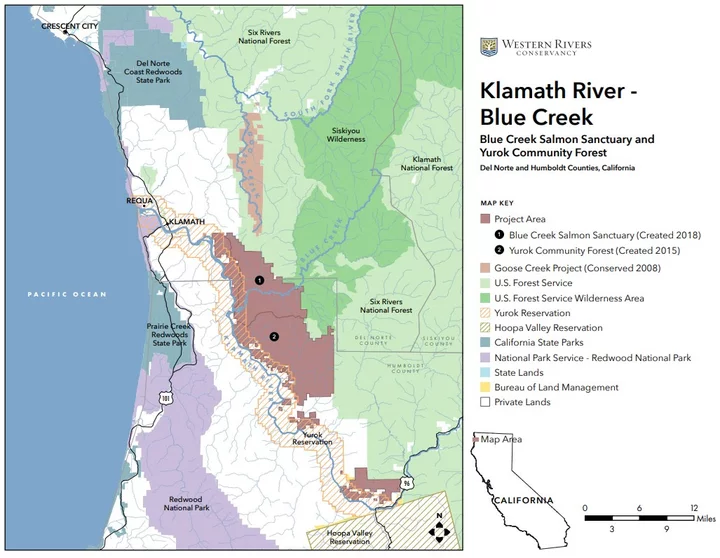

Today, Western Rivers Conservancy (WRC), the Yurok Tribe, the California Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB) and the California State Coastal Conservancy (CSCC) announce completion of the largest single “land back” deal in California history, marking a milestone achievement for conservation and Tribal sovereignty. The 73 square miles of land along the eastern side of the lower Klamath River are now owned and managed by the Yurok Tribe as the Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary and Yurok Tribal Community Forest. (See map below.) Establishing Tribal ownership safeguards the long-term health of this critical ecosystem and culturally significant sites along the Klamath, which is home to one of the most important fall Chinook salmon runs on the West Coast. The conveyance of these lands to the Tribe has more than doubled the Tribe’s land holdings; both California state agencies provided crucial funding to enable this transfer of ownership.

“On behalf of the Yurok people, I want to sincerely thank Western Rivers Conservancy for their longtime partnership and commitment to return a major part of our homeland. The impact of this project is enormous,” said Joseph L. James, the chairman of the Yurok Tribe. “In working together for over two decades establishing the Community Forest and Salmon Sanctuary, we are forging a sustainable future for the fish, forests and our people that honors both ecological integrity and our cultural heritage.”

The 47,097 acres of ancestral lands, located in the lower Klamath River watershed, play a crucial role in improving the health of Blue Creek, which carries great spiritual significance for the Yurok Tribe and is a crucial cold-water lifeline to the fish of the Klamath River. The forests, river lands and prairies they contain provide habitat for numerous imperiledspecies, including coho and Chinook salmon, marbled murrelet, northern spotted owl and Humboldt marten. Blue Creek serves as a vital cold-water refuge for salmon, steelhead and other fish in an era of climate change.

Nelson Mathews, president of Western Rivers Conservancy, emphasized the broader environmental benefits of this achievement: “This project exemplifies the power of partnership, showcasing how conservation efforts and the land back movement can come together to benefit the rivers, fish, wildlife and people of an entire landscape. After more than 20 years of close collaboration with the Yurok Tribe, we have together achieved this magnificent conservation success while ensuring these lands and waters are in the hands of those most deeply committed to their future health and sustainable use. Blue Creek and its watershed are critical to the health of the entire Klamath fishery. The Yurok Tribe has the resources and the deep cultural connections that sustained this land for millennia, and now they can continue to do so.”

About the Blue Creek Project

Today’s announcement marks the completion of Western Rivers Conservancy’s 23-year effort to convey 47,097 acres of critical lands along the Klamath River and encompassing the lower Blue Creek watershed, including their confluence, to the Yurok Tribe. From 2009 through 2017, WRC acquired or facilitated transfer of the lands from Green Diamond Resource Company in multiple phases; conveyance of the lands from WRC to the Yurok has happened in multiple phases as well. The conveyance of the final 14,968 acres from WRC to the Yurok Tribe closed on May 30, 2025.

The historic 47,097-acre land transfer, at a purchase price of $56 million, encompasses the entire lower half of the Blue Creek watershed, 25 miles of the eastern bank of the Klamath River and dozens of miles of smaller salmon-bearing tributary streams, including Blue Creek, Bear Creek, Pecwan Creek and Ke’Pel Creek. The lands were owned and managed as commercial timberland by Green Diamond and its predecessor Simpson Logging Company for nearly 100 years. These lands are the ancestral homelands of the Yurok Tribe, who have lived along the Klamath River and depended on its salmon since time immemorial. This collaboration between a nonprofit conservation organization and a Native American Tribe reflects the growing intersectional movement between land back and environmental stewardship in the United States.

To pay for the project, WRC pieced together an innovative funding strategy that brought together $56 million in private capital, low interest loans, tax credits and carbon credit sales. Of that, only $8 million was through direct public grants. The private funding included traditional sources, such as gifts from private foundations, corporations and philanthropic individuals, as well as nontraditional sources like the sale of carbon credits, which will continue to support the project, and capital generated through the New Markets Tax Credit program of the U.S. Department of the Treasury.

In addition to raising the funds to purchase the land, WRC will also transfer $3.3 million generated through the sale of carbon credits to the Yurok Tribe to be used for future stewardship of the property. When project costs are included, the full value of the Blue Creek conveyance is over $70 million.

Photo by Peter Marbach.

A New Salmon Sanctuary and Tribal Community Forest

Conveyance of the final lands from WRC to the Yurok Tribe completes the Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary, a 14,790-acre cold-water refuge surrounded by forest lands that will now be managed for forest complexity and old-growth health for the benefit of the Klamath River’s fish and wildlife. The entirety of Blue Creek is now permanently protected, from its headwaters and upper reaches in the Siskiyou Wilderness to its confluence with the Klamath River.

Located 16 miles upstream from the mouth of the Klamath, Blue Creek provides the first cold-water refuge in the river for migrating salmon and steelhead, allowing summer and fall-run fish to lower their body temperatures enough to survive their long journey to upstream spawning grounds. Blue Creek is thus an essential component of the overall health of the Klamath River and the entirety of its salmon runs, especially as the removal of all the Klamath dams has reopened vast spawning habitat in the upper river.

The other 32,307 acres of redwood and mixed conifer forest outside the Salmon Sanctuary now constitute the Yurok Tribal Community Forest. Already more than a decade in the making, the forest is being allowed to recover from nearly a century of industrial logging that left both the forest and the streams in need of extensive restoration. The Tribe’s sustainable forestry practices are focused on putting the Yurok Community Forest on a path to become more diverse and mature by increasing the time between harvests. The Community Forest provides jobs for Tribal members in forestry and restoration, helping build the future for the Yurok people. It also helps mitigate the effects of climate change. Recent research has demonstrated that redwood forests can store more carbon per acre than any other type of forest and that second-growth (previously logged) redwood forests have the greatest potential to accumulate carbon even faster than old-growth trees.

From 2013 until present, WRC worked in a formal co-management agreement with the Yurok Tribe to conduct the necessary planning and implementation for forest restoration and management, aquatic restoration, logging road removal and preparations for the final conveyance of land. This agreement served to build capacity and expertise for both WRC and the Yurok, as they collaborated to meet grant requirements, finalize the management plan and initiate on-the-ground restoration projects and chart the future of both the Salmon Sanctuary and the Community Forest.

Photo by Thomas Dunklin.

Western Rivers Conservancy and the Yurok Tribe’s Shared Vision for Blue Creek

WRC and the Yurok Tribe’s shared vision has been to create a sustainable and inclusive model of land management that prioritizes Blue Creek and the Klamath River and honors both ecological integrity and cultural heritage. The project’s outcomes benefit both land conservation and cultural repatriation.

“Everyone has a vested interest in seeing the Klamath salmon runs survive and thrive,” said WRC President Emerita and co-founder Sue Doroff, who launched the Blue Creek project and oversaw it until her retirement in June 2024. “Millions of dollars and immeasurable human energy are being invested in the Klamath River right now. There are two things that are key to the success of this massive effort to save this river and its salmon: Blue Creek and the Yurok people. I am honored beyond words to have worked together with the Yurok to ensure the Klamath and its fish and wildlife will have a salmon sanctuary and cold water refuge where they need it most.”

The Klamath River is in prolonged recovery from more than a century of logging, dams, gold mining and other human activities. In August 2024, the last three of four dams were removed from the upper Klamath River. Initiated by Klamath Basin tribes, the removal of these dams reopened more than 400 miles of salmon habitat in the upper river for the first time in over a century.

“The dams were the single biggest impediment to salmon production on the Klamath because they had such a negative influence on the river ecosystem. Through dam removal, protection and restoration of critical tributaries like Blue Creek and proper water management, we will restore the fish runs that sustained us and this entire region,” said Barry McCovey, director of the Yurok Fisheries Department, which employs nearly 100 scientists and technicians.

Western Rivers Conservancy – A Leader in Land Back

For more than 30 years, WRC has taken the lead in marrying conservation and tribal land-return outcomes, working with tribal nations to permanently protect rivers and the lands that sustain them. WRC and its many tribal partners, who are the original stewards of riverlands across the West, make natural conservation partners given that tribal nations often possess the resources, foresight, expertise and commitment to restore and conserve these vital places in perpetuity. Most recently, WRC conveyed 327 acres of the Little Sur River and surrounding ancestral redwood forest to the Esselen Tribe of Monterey County along California’s central coast. A complete list and history of WRC’s Tribal Nations partnerships are available here.

Project Funding

State funding and support for the Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary and Yurok Tribal Community Forest was provided by the California Wildlife Conservation Board (WCB), California State Coastal Conservancy (CSCC), California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the California Environmental Enhancement and Mitigation Program.

“Returning these lands to the Yurok Tribe is an unprecedented step forward for the Klamath River, and it comes at a critical moment following the removal of the Klamath River dams. Returning ancestral lands to Native American tribes is an essential step in restoring ecological balance and health,” said Jennifer Norris, executive director of the California Wildlife Conservation Board. “WCB is proud to be part of this truly historic achievement, both for the Yurok people and as part of the broader effort to guarantee the long-term survival of the Klamath’s salmon and the wildlife of Northern California.”“Thanks to this incredible group of partners, the Blue Creek Salmon Sanctuary and Yurok Tribal Community Forest have become one of California’s great conservation successes—one that will nurture tribal resilience for the Yurok people, improve conditions for the Klamath River’s salmon and wildlife and carry forward the Coastal Conservancy’s mission of improving climate resilience on the California Coast,” said Amy Hutzel, executive officer of the California State Coastal Conservancy.

Additional support came from Compton Foundation, Lisa and Douglas Goldman Fund, George F. Jewett Foundation, The Kendeda Fund, Giles W. and Elise G. Mead Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation/Acres for America and Walmart Stores, Inc., Natural Resources Conservation Service, David and Lucile Packard Foundation, the Land-Sea Connection program of Resources Legacy Fund made possible by the Keith Campbell Foundation for the Environment, U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities, Inc., U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, Weeden Foundation and The Wyss Foundation.

Please visit the Klamath River/Blue Creek project web page for additional information on this historic achievement, including a complete list of project funders and funding details.

Photo by Dave Jensen.

Humboldt County Animal Shelter Offering Free Adoptions During ‘Adopt-a-Pet Day’ This Saturday

LoCO Staff / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 10:24 a.m. / Animals

A few of the currently adoptable pets at the Humboldt County Animal Shelter. | Images via Facebook.

###

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On Saturday, June 7, the Humboldt County Animal Shelter will offer free adoptions as part of the second annual California Adopt-a-Pet Day, a statewide event aiming to get 5,000 animals into loving homes— in just one day.

The shelter will be open from 10:00 a.m. to 4:00 p.m., with adoption fees completely waived for all available pets. Costs are covered in part by the ASPCA and event organizers.

Important info for adopters:

- An approved application is required before meeting any animals.

- To view adoptable pets and apply online ahead of time, visit: humboldtgov.org/Animal-Shelter

- If you’re adopting a dog and already have dogs at home (or on the property), bring them along to meet your potential new pet.

- Renters: Applying in advance is especially important so staff can contact your landlord.

Why adopt now?

- Every animal adopted makes space for another in need. When you adopt from our shelter, your new pet comes spayed/neutered, vaccinated, and microchipped—ready to head home with you.

- Last year, this event helped over 3,600 animals get adopted in one day. This year, the goal is even bigger.

Join us. Bring a friend. Go home with a new one!

California Is Failing to Provide a Vital Safeguard Against Wrongful Convictions

Anat Rubin / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 7:55 a.m. / Sacramento

A courtroom in San Diego on Oct. 8, 2023. Photo by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

A CalMatters investigation has found that poor people accused of crimes, who account for at least 80% of criminal defendants, are routinely convicted in California without anyone investigating the charges against them.

Close to half of California’s 58 counties do not employ any full-time public defense investigators. Among the remaining counties, defendants’ access to investigators fluctuates wildly, but it’s almost always inadequate.

The cost of this failure is steep, for individual defendants and for the integrity of California’s criminal justice system.

Defense investigators interview witnesses, visit crime scenes, review police reports and retrieve video surveillance footage that might prove the defendant was on the other side of town when a crime was committed, or that an assault was an act of self-defense. They do work that most lawyers are not trained to do. Without them, police and prosecutorial misconduct — among the most common causes of wrongful convictions — remain unchecked, significantly increasing the likelihood that people will go to prison for crimes they did not commit.

In our new investigation, we examine the consequences of this pervasive issue through a reopened kidnapping and murder case in Northern California’s Siskiyou County.

Here are the takeaways:

1. Of the 10 California counties with the highest prison incarceration rates, eight have no defense investigators on staff.

The lack of investigators affects counties throughout the state, from poor, rural areas like Siskiyou to the state’s largest and most well-funded public defense offices.

Los Angeles employed just 1 investigator for every 10 public defenders — one of the state’s worst ratios, according to 2023 data from the California Department of Justice. Only seven California counties met the widely accepted minimum standard of 1 investigator for every 3 attorneys.

2. The situation is most alarming in the 25 California counties that don’t have dedicated public defender offices and pay private attorneys.

Most of these private attorneys receive a flat fee for their services, and the cost of an investigator would eat away at their profits. Some counties allow contracted attorneys to ask the court for additional funds for investigations, but court records show the attorneys rarely make those requests.

In Kings County, which has one of the highest prison incarceration rates in California, contracted attorneys asked the court for permission to hire an investigator in 7% of criminal cases from 2018 to 2022. In Lake County, attorneys made those requests in just 2% of criminal cases over a three-year period; in Mono County, it was less than 1%. To earn a living from meager county contracts, research shows, private attorneys and firms must persuade defendants to accept plea deals as quickly as possible. An investigation is an expensive delay.

3. Prosecutors have an overwhelming advantage when it comes to investigator staffing.

In Riverside, the district attorney has 30% more lawyers than the public defender but 500% more investigators, state data shows, in addition to the support of the county sheriff and various municipal police departments.

This pattern repeats throughout the state. In what is supposed to be an adversarial legal system, indigent defendants and their attorneys are often on their own, facing an army of investigators who are working to secure a conviction.

4. Hidden in the data is the greatest tragedy of failing to investigate cases: wrongful convictions.

The National Registry of Exonerations is filled with cases in which convictions were overturned when someone finally looked into the prisoner’s claims, years or even decades after they were imprisoned.

Hundreds of those cases are in California. In one exoneration out of Fresno, Innocence Project investigators found nine witnesses who corroborated their client’s alibi: He was more than 25 miles away at a birthday party at the time of the crime. In a recent case out of Los Angeles, investigators found evidence of their client’s innocence in a police detective’s handwritten notes, material that had been included in a file turned over to the defense before trial. If their cases had been investigated on the front end, these men might have been spared a combined 30 years in prison.

Maurice Possley, the exoneration registry’s senior researcher, said that a failure to investigate is at the heart of most of the registry’s 3,681 cases.

When he looks at the evidence that overturned these convictions, he’s astounded the defense didn’t find it when the case was being prosecuted.

“If someone had just made the effort,” he said. “This was all sitting there.”

5. California, once a leader in public defense, has fallen far behind.

The nation’s first public defender office opened in Los Angeles in 1913. By the time the U.S. Supreme Court established in 1963 that defendants have the right to an attorney in state criminal proceedings, more than a dozen California counties were already providing free representation to poor people accused of crimes.

As the nation caught up, California slipped behind. The state kept its defender system entirely in the hands of its counties. Today, it is one of just two states — alongside Arizona — that don’t contribute any funding to trial-level public defense, according to the Sixth Amendment Center. The state does not monitor or evaluate the counties’ systems. There are no minimum standards and, for many defendants, no investigations — even in the most serious cases.

Investigations affect every part of the criminal justice process. They’re not just about figuring out whether a client is innocent. Even if a case is moving toward a plea deal, an investigation can turn up information that forces a prosecutor to reduce the charge or compels a judge to grant bond or shorten a prison sentence.

Lawyers are discouraged from interviewing witnesses on their own. If a witness later changed their story or disappeared before trial, the attorney could have to testify on their client’s behalf and recuse themself from the case.

6. This is a national problem.

In 2007, the Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted a census of the nation’s public defender offices. It found that 40% had no investigators on staff and that 93% failed to meet the National Association for Public Defense’s industry standard of at least 1 investigator for every 3 attorneys.

The study made it clear that, across the country, investigators were seen as a luxury, not a necessity. CalMatters interviews with top public defenders in several states, along with recent reports examining indigent defense systems, suggest that’s still the case.

In Mississippi, only eight of the state’s 82 counties have public defender offices. The rest rely on private attorneys who are paid a flat fee — one that rarely covers the cost of an investigator. A 2018 report found that, in many Mississippi counties, with the exception of murder cases, the attorneys “never hire investigators and have no time to investigate cases themselves.” Appointed attorneys told researchers they would “get laughed out of court” for requesting additional funds for an investigator.

Public defender systems that are funded and controlled by state legislatures also have severe investigator shortages. The head public defender in Arkansas, Greg Parrish, said he has only 12 staff investigators, responsible for assisting in felony cases, including capital cases, in all of the state’s 75 counties. Minnesota’s top public defender, William Ward, said he is trying to maintain a ratio of at least 1 investigator for every 7 public defenders but knows that’s not enough. “I would rather have a great investigator and an average lawyer than an average investigator and a great lawyer,” he said. “Investigators make all the difference on a case.”

7. New York stands as a model of how to reform the system.

New York was once very similar to California. Its counties managed their own public defender systems, without much input or funding from the state, until a class-action lawsuit, settled in 2015, led to statewide changes.

New York created an office tasked with improving public defense, eventually giving it some $250 million to dole out each year. Counties that take the money must prioritize certain aspects of public defense, including investigations. In a recent report to the agency overseeing the effort, these counties consistently said the ability to investigate cases was among the most profound impacts of the new funding. Some described specific cases that ended in acquittal or significantly reduced charges as a result.

California was also sued over claims it failed to provide competent defense. To settle the lawsuit, filed in Fresno County, Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2020 expanded the scope of the Office of the State Public Defender, which had previously handled death penalty appeals, to include support and training for county-based public defender systems.

But the governor committed only $10 million in one-time grants to the effort, and that money has since run out.

The Man Who Unsolved a Murder: If You’re Accused of a Crime, Will Someone Investigate Your Side of the Story? In California, There’s No Guarantee.

Anat Rubin / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 7:39 a.m. / Sacramento

A view down 2nd Avenue in Happy Camp on Dec. 13, 2024. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

On Aug. 28, 1976, sometime between 7:30 and 8 p.m., a 6-year-old boy named Willie Cook disappeared from the bed of his father’s pickup in Happy Camp, a secluded logging community in Northern California’s Klamath National Forest. Willie’s father, Bill Cook, had been working on his lawn mower at a repair shop in the center of town. When he was done, he told Willie to wait in the truck with the family dog while he ducked into the bar across the street. He was gone less than 20 minutes. The sun had set behind the mountains, but there was still light in the sky.

Cook searched the area on foot, then drove in the direction of the family home. After he circled town a couple more times, he called law enforcement to report that his son was missing. He gave the local deputy a description: Willie was 42 inches tall and weighed 45 pounds. He was wearing a black baseball jersey, jeans and white tennis shoes. His right eye was blue, and his left eye was a mix of blue and brown. He was, Cook said, “a very good boy, and had never wandered off in the past.”

By midnight, 150 people were searching for Willie, combing the dense woods surrounding the town. But Cook did not believe his son was lost in the forest. From the moment he had walked out of that bar, he was certain that someone had taken him. “I felt it,” he said. “I felt it all over.”

Willie’s body was discovered six months later in a small cardboard barrel at a campground along the Klamath River, more than 50 miles from Happy Camp. The Siskiyou County sheriff’s office launched a murder investigation but never solved the case.

After 32 years, sheriff’s deputies got their first big break when a man came forward to say he had witnessed the kidnapping. Steve Marshall was only 10 years old in 1976, but his memory of that August day was vivid: He was sitting alone in his mother’s blue station wagon, parked outside the Headway Market, within view of the repair shop and the old bar. He was eating a vanilla ice cream cone. His brother was inside the market with their mother. They would be having spaghetti for dinner that night — his favorite.

The Headway Market in Happy Camp. Photo via the Class of 1975 Happy Camp High School Yearbook

Marshall seemed to remember what happened next as though it were unfolding in slow motion: The sound of a logging truck as it roared past. Willie’s Labrador wagging his tail. And a young man in blue jeans and a vest, his long hair in two braids, standing on the opposite side of the street, staring at the boy and his dog.

Marshall recognized him. His name was Gregory Nelson. And Marshall said he had a clear view of him as he crossed the street, grabbed Willie, shoved him into a VW bus and drove off, disappearing down the one-lane highway that cut through town. Marshall had tried to tell his mother what he’d seen, but she’d brushed him off. For the next few decades, he mostly kept it to himself. But the memory, he said, had haunted him.

The Siskiyou sheriff arrested Nelson, then 51, and brought him in for questioning. He had a couple grams of methamphetamine and several syringes in his pocket. After two days of interrogation, he confessed. The following day, the sheriff told a local reporter that a cold case is like a puzzle. “After 32 years, we’re finally getting the pieces put together.”

Nelson was charged with kidnapping and murder. Siskiyou’s chief public defender, Lael Kayfetz, thought there was little chance of overcoming a signed confession and an eyewitness account. Then the prosecutors turned over the recordings of Nelson’s interrogation. When Kayfetz watched the footage, she said, “my eyeballs fell out of my head.”

She realized she needed to test the claims against her client, but she couldn’t do it on her own. “I’m an expert on the law,” Kayfetz said. “I’m not an expert on getting the facts.” She needed an investigator.

The prosecutors were working closely with detectives at the sheriff’s office, issuing warrants and building a case. They also employed their own team of five investigators.

That year, Siskiyou County’s public defender didn’t have a single defense investigator on staff.

***

Lawyers have a constitutional obligation to investigate every case. But a CalMatters investigation found that poor people accused of crimes, who account for at least 80% of criminal defendants, are routinely convicted in California without anyone investigating the charges against them. Close to half of California’s 58 counties do not employ any full-time public defense investigators. Among the remaining counties, defendants’ access to investigators fluctuates wildly, but it’s almost always inadequate.

See also:

California Is Failing to Provide a Vital Safeguard Against Wrongful Convictions

The cost of this failure is steep, for individual defendants and for the integrity of California’s criminal justice system. Of the 10 California counties with the highest prison incarceration rates, eight have no defense investigators on staff, according to an analysis of staffing and prison data.

The lack of investigators affects counties throughout the state, from poor, rural areas like Siskiyou to the state’s largest and most well-funded public defense offices. Los Angeles employed just 1 investigator for every 10 public defenders — one of the state’s worst ratios, according to the most recent data from the California Department of Justice. Only seven California counties met the widely accepted minimum standard of 1 investigator for every 3 attorneys.

The situation is most alarming in the 25 California counties that don’t have dedicated public defender offices and pay private attorneys to represent indigent people in criminal court. Most of these attorneys receive a flat fee for their services, and the cost of an investigator would eat away at their profits. Some counties allow contracted attorneys to ask the court for additional funds for investigations, but court records show the attorneys rarely make those requests.

In Kings County, which has one of the highest prison incarceration rates in California, contracted attorneys asked the court for permission to hire an investigator in 7% of criminal cases from 2018 to 2022. In Lake County, attorneys made those requests in just 2% of criminal cases over a three-year period; in Mono County, it was less than 1%. To earn a living from meager county contracts, research shows, private attorneys and firms must persuade defendants to accept plea deals as quickly as possible. An investigation is an expensive delay.

Defense investigators interview witnesses, visit crime scenes, review police reports and retrieve video surveillance footage that might prove the defendant was on the other side of town when a crime was committed, or that an assault was an act of self-defense. They do work that most lawyers are not trained to do. Without them, police and prosecutorial misconduct — among the most common causes of wrongful convictions — remain unchecked, significantly increasing the likelihood that people will go to prison for crimes they did not commit.

“Law is important, but the facts are what influences the law,” said Aditi Goel, executive director of the Sixth Amendment Center, a national nonprofit focused on improving indigent defense. “The heart of a case is what happened.”

***

In 2008, Kayfetz and her four staff attorneys were left to sleuth most cases on their own, and they worried about what they might be missing. Siskiyou County provided them with a small budget to contract with a private investigator, but the Nelson case, which had already spanned three decades, would burn through their entire investigation fund for the year. Still, Kayfetz didn’t feel as though she had a choice. Nelson was facing life in prison, and the sheriff was in the papers talking about closure for the Cook family.

She called Rob Shelton, an investigator who had spent most of the previous two decades in law enforcement — first with the Coast Guard, then as a harbor patrol officer in Ventura, and recently as a probation officer for Siskiyou. He’d crossed over into defense investigations, and this would be his first homicide case for the public defender’s office.

Lael Kayfetz, the Siskiyou County public defender, realized she needed to test the claims against her client, but she couldn’t do it on her own. Photo by Christie Hemm Klok for CalMatters

Nelson’s mug shot had by then been published on the front page of the Siskiyou Daily News. His hair was graying, and his cheeks were deeply sunken. Shelton knew that look. He had seen it on the probationers he had monitored, people whose hard lives were etched into their faces. He had come to view their struggles with the law as a symptom of their poverty and addiction. But he also believed Nelson was guilty. It was hard for him to imagine that the sheriff would pursue a case without concrete evidence, and even harder to believe that the district attorney would push it toward trial.

Kayfetz handed Shelton the records she’d gotten from the prosecutors, and he spent those first few weeks combing through old police reports.

As he made his way through the documents, he found black-and-white copies of photographs the sheriff’s deputies had taken as they searched Happy Camp in the days after Willie’s disappearance: The chain-saw repair shop where the truck had been parked. The old bar across the street. And a building that looked as though it had recently burned down. It was familiar to Shelton, though he couldn’t initially place it.

Then one day, while he was staring at the photo, it clicked. It was the Headway Market, where Marshall said his mother had been shopping when he witnessed the kidnapping.

“There was no store,” Shelton said. “There was just ruins.”

Shelton walked down the street to the Siskiyou County assessor’s office to pull records on the property. The market, he learned, had burned down a few months before Willie Cook was taken.

***

California is the birthplace of public defense. The nation’s first public defender office opened in Los Angeles in 1913. By the time the U.S. Supreme Court established in 1963 that defendants have the right to an attorney in state criminal proceedings, more than a dozen California counties were already providing free representation to poor people accused of crimes.

As the nation caught up, California slipped behind. The state kept its defender system entirely in the hands of its counties. Today, it is one of just two states — alongside Arizona — that don’t contribute any funding to trial-level public defense, according to the Sixth Amendment Center. The state does not monitor or evaluate the counties’ systems. There are no minimum standards, and for many defendants there are no investigations — even in the most serious cases.

Meanwhile, prosecutors have robust, in-house investigative teams. In Riverside, the district attorney has 30% more lawyers than the public defender but 500% more investigators, state data shows, in addition to the support of the county sheriff and various municipal police departments. This pattern repeats throughout the state. In what is supposed to be an adversarial legal system, indigent defendants and their attorneys are often on their own, facing an army of investigators who are working to secure a conviction.

Hidden in that data is the greatest tragedy of failing to investigate cases: wrongful convictions. The National Registry of Exonerations is filled with cases in which convictions were overturned when someone finally looked into the prisoner’s claims, years or even decades after they were imprisoned.

Hundreds of those cases are in California. In one exoneration out of Fresno, Innocence Project investigators found nine witnesses who corroborated their client’s alibi: He was more than 25 miles away at a birthday party at the time of the crime. In a recent case out of Los Angeles, investigators found evidence of their client’s innocence in a police detective’s handwritten notes, material that had been included in a file turned over to the defense before trial. If their cases had been investigated on the front end, these men might have been spared a combined 30 years in prison.

Maurice Possley, the exoneration registry’s senior researcher, said that a failure to investigate is at the heart of most of the registry’s 3,600 cases.

When he looks at the evidence that overturned these convictions, he’s astounded the defense didn’t find it when the case was being prosecuted.

“If someone had just made the effort,” he said. “This was all sitting there.”

***

Shelton was in his early 40s when he got the Nelson case. He had been living in Siskiyou for years, but he hadn’t shed his Southern California accent. He was soft-spoken, smiled often, and had the easy mannerisms of someone who had spent a lot of time at the beach. It didn’t take long for him to build a rapport with Nelson, and he visited him frequently at the Siskiyou County jail. Nelson told him he had no memory of the events that Marshall had recounted for the deputies. Those claims of innocence had sounded hollow to Shelton, but the picture of the burned market changed his thinking about the case. Now he wondered whether anything Marshall had said was true.

As he dug deeper into the case, defense investigator Rob Shelton began to doubt the prosecution’s narrative of the crime. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Detectives with the Siskiyou sheriff’s office had interviewed Marshall several times in October 2008, a month before they arrested Nelson. Kayfetz requested those recordings, and she and Shelton listened to the tapes.

In the first interview, Marshall initially hedged his words. When a detective asked him whether he saw Willie — who was Marshall’s cousin — on the day he was taken, he said that it “seemed like” he did. Then he said that he watched Nelson grab Willie and put him in the van, where another man was crouching in the passenger seat.

“You saw that?” the detective asked.

“That was with my own eyes I saw that,” Marshall said.

Minutes later, in a second accounting, Marshall added an accomplice — the woman who would later become Nelson’s wife slid the van door open and jumped inside before they drove off. Three days later, an additional woman appeared in the story — the wife’s sister — and the man in the passenger seat was gone.

It was remarkable to Shelton that the detectives didn’t challenge Marshall on these discrepancies. Each time he told the story, he added details — the ice cream flavor, the face his brother made at him as he walked into the market.

When a detective asked whether Marshall had said anything to his mother when she came back, he replied that he had tried but that his brother was teasing him. “That’s why I just threw it aside,” he said. “Because my brother, he made me mad.” Marshall eventually told his mother what had happened, he said, but neither of them mentioned it to Cook when they joined the search party later that night.

A newspaper clipping related to the Willie Cook murder case from the Sept. 15, 1976 edition of the Sacramento Bee.

In a separate interview with detectives, Marshall’s mother corroborated his account. “I should have listened to him,” she said. “It was like he was trying to tell all of us that he had seen who took Willie. Is that possible? But nobody would believe him, because he was a little boy.”

In one of the recordings, the detectives alluded to some kind of legal trouble Marshall was facing. “You’re taking care of us, and we’re going to scratch your back in return,” a detective had promised him.

During his fourth and final recorded interview with detectives, Marshall had something new to share: He wasn’t just a witness to Willie’s kidnapping. He was also a witness to his murder. Months after the kidnapping, Marshall said, he took a trip with his father to visit his grandparents on the Hoopa reservation, some 70 miles from Happy Camp. It was there, he said, while hiding behind a tree in the back of Nelson’s house, that he saw Nelson take Willie out of a locked van and heard him say, “This is the last time you’re going to even breathe air.”

“I’m standing right there, and I’m watching him from that tree,” he told a detective. “I’m watching him put his hands around that little boy and strangle him until that little boy was dead.”

The detective conducting the interview initially seemed alarmed by this change in the story. She told Marshall that her sergeant would need to speak with him “about the differences in your statement from the first time that we talked to you.” She left the room but came back alone. “I think you and I pretty much clarified everything,” she said.

In her report, she wrote that Marshall had witnessed the murder “four or five days” after the kidnapping. That was an error — Marshall repeatedly said four or five months had passed between the kidnapping and the murder, according to a transcript of the interview. But that error would find its way into Nelson’s confession.

From Marshall’s testimony, police and prosecutors created their theory of the crime, interview transcripts and court filings show. They proposed Nelson was a pawn in a scheme hatched by his sister-in-law — one of the women Marshall named as an accomplice — who wanted to hurt Cook by taking his son. Maybe she had been jealous of his success. Maybe she wanted to avenge her husband, who had been tried, and later acquitted, for the murder of Cook’s brother.

A newspaper clipping related to the Willie Cook murder case from the Feb. 23, 1977 edition of The Dunsmuir News.

Nelson and his sister-in-law were both Native American. To Kayfetz, law enforcement’s assumption that they would kidnap and kill a child as an act of revenge, or in a fit of jealous rage, played into racial stereotypes and became the “underlying stench” of the case.

The evidence had suggested that Willie was kidnapped by a sexual predator. His body was naked when it was discovered. Now law enforcement posited he was murdered in a family feud.

Even Willie’s father initially had a hard time believing this theory. “I just can’t imagine that,” Cook told a detective in 2008. “Over something that stupid? My gut feeling is no.”

But the deputies were insistent. Eventually, Cook began to come around to the possibility that Nelson was the killer.

Deputies exhumed Willie’s body, but it did not provide any new evidence. Far too much time had passed.

***

When Shelton began working on the case, he was shocked whenever he discovered that law enforcement had made a mistake, or that prosecutors had failed to turn over a key document.

He would burst into Kayfetz’s office, saying, “You’re not gonna believe this!” And Kayfetz would tell him, dryly, “There’s no Santa or Easter Bunny, either.”

He would soon lose that sense of disbelief.

As the investigation progressed, Shelton became convinced that Marshall had invented most of his story. Marshall had given detectives the names of other potential witnesses, but those turned out to be dead ends. Still, Siskiyou’s district attorney, Kirk Andrus, seemed determined to move forward, and Nelson was losing hope.

Then, one day, while he was looking through old police files, Shelton found a list of materials the deputies had entered into evidence in 1976. It included references to interviews they recorded with potential witnesses. Shelton scanned the list and saw Marshall’s name. The prosecution’s star witness had spoken to officers just days after Willie disappeared. If law enforcement still had access to these recordings, they hadn’t shared them with the defense.

When Kayfetz asked the district attorney’s office to turn over the evidence, the prosecutors said they didn’t have it. But Shelton learned the tapes from the case had recently been digitized and enhanced by the Justice Department, at the request of the Siskiyou detectives. Kayfetz filed a second motion to get the recordings. When the judge ordered the prosecutors to explain how the tapes had gone missing, they said that they had found them and that they had been lost on a detective’s desk, according to court documents.

Willie Cook was sitting in the open bed of his father’s pickup truck in front of this building in Happy Camp when he was kidnapped. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Soon Kayfetz and Shelton were listening to Marshall, 10 years old, answering questions about the evening Willie disappeared. There was no ice cream. Marshall’s brother was not in the car, but his older sister was. Their mom didn’t go to the grocery store, but she did stop at a liquor store to buy a TV Guide. When they drove through the center of town, Marshall waved to Willie, who was sitting in his dad’s truck.

“I said, ‘Hi, Willie,’ and he said ‘Hi’ back. And I said, ‘Where’s your dad?’ And he said, ‘He’s in the bar.’” When they drove by again, Willie was gone.

“Am I allowed to go now?” Marshall asked the detective.

In a separate interview that same day, Marshall’s mother corroborated her son’s account. Nobody mentioned Nelson. Nobody said anything about witnessing a kidnapping.

***

Shelton felt as though they were pulling a string and unraveling the district attorney’s case.

He discovered that Marshall had a motive for becoming useful to law enforcement in the fall of 2008. He had violated the terms of his probation for a drunken-driving conviction and was facing prison, but police kept the violation off his record, Shelton said.

Kayfetz was encouraged by the evidence that was mounting in Nelson’s favor, but if the case went to trial, she would have to contend with the fact that he had confessed to the crime.

She sent the footage of his interrogation to Richard Leo, a University of San Francisco law professor and one of the nation’s foremost experts on coerced confessions, and asked him to testify on Nelson’s behalf. She couldn’t afford his fee — she was already pushing the outer limits of her budget. And when she first reached out, Leo told her he didn’t have time to take on another case. But she begged him to watch the footage before he made up his mind.

Even now, almost 17 years later, he remembers how stunned he had been when he first saw it. Among the 2,400 cases he’s consulted on, he said, the Nelson case stands out as one of the most egregious examples of a coerced confession he has ever seen. He called it “a form of psychological torture.”

“There’s a sequence to this — a long interrogation, lie to the suspect about evidence, attack the suspect’s denials, cause him to doubt his memory,” he said. “Sometimes you see this person denying and admitting at the same time: ‘I couldn’t have done this. I have no memory. You’re telling me I did this, maybe I did this.’”

Leo said Nelson was subjected to almost every tactic known to lead to a false admission of guilt. He agreed to do the case for a reduced fee — a “bro deal,” Kayfetz called it — in exchange for permission to include it in a future book.

More than 12% of the wrongful convictions listed on the National Registry of Exonerations involved false confessions. In a recent case in San Bernardino, police officers pushed a man to admit to killing his father after he called police to report him missing. During a marathon interrogation, officers told the man they had conclusive evidence of his guilt and got him to agree with a gruesome scenario that they had pulled, it seems, from thin air. A few hours after he confessed, police officers located the man’s father. He was alive and well.

***

In 2007, the Bureau of Justice Statistics conducted a census of the nation’s public defender offices. It found that 40% had no investigators on staff and that 93% failed to meet the National Association for Public Defense’s industry standard of at least 1 investigator for every 3 attorneys.

The study made it clear that, across the country, investigators were seen as a luxury, not a necessity. CalMatters interviews with top public defenders in several states, along with recent reports examining indigent defense systems, suggest that’s still the case.

In Mississippi, only eight of the state’s 82 counties have public defender offices. The rest rely on private attorneys who are paid a flat fee — one that rarely covers the cost of an investigator. A 2018 report found that, in many Mississippi counties, with the exception of murder cases, the attorneys “never hire investigators and have no time to investigate cases themselves.” Appointed attorneys told researchers they would “get laughed out of court” for requesting additional funds for an investigator.

Public defender systems that are funded and controlled by state legislatures also have severe investigator shortages. The head public defender in Arkansas, Gregg Parrish, said he has only 12 staff investigators, responsible for assisting in felony cases, including capital cases, in all of the state’s 75 counties. Minnesota’s top public defender, William Ward, said he is trying to maintain a ratio of at least 1 investigator for every 7 public defenders but knows that’s not enough. “I would rather have a great investigator and an average lawyer than an average investigator and a great lawyer,” he said. “Investigators make all the difference on a case.”

Colin Reingold remembers one case in particular from his time as a public defender in Louisiana’s Orleans Parish. His client was accused of breaking into a car, but he insisted he was entering the car to leave a note offering to do yard work.

Reingold sent an investigator to the car owner’s house, but there was no one home. His client had two prior felonies, and a car burglary would qualify him for a life sentence. When the prosecutor offered 10 years in exchange for a guilty plea, Reingold advised him to take the deal. But his client begged him to find the note, he said.

That year, Orleans Parish had 65 public defenders and three investigators. The one assigned to the man’s case refused to give up. She tried for six weeks to find the car’s owner. In the week before the plea hearing, she stopped by his home almost daily. One evening, he answered the door. He said, “Oh yeah, I still have that note!”

Reingold presented the note as evidence, and his client was released from jail.

It was, he said, a rare stroke of luck. “The scary thing is, we don’t know all the other times we’ve missed things like that.”

***

Just weeks before Nelson’s trial was set to begin, the prosecution was still turning over discovery materials.

Shelton began to make his way through the latest batch. Many of the documents were familiar — duplicates of reports and transcripts he had already reviewed. But he stumbled on a few photographs, tucked into the file, that he hadn’t seen before. In the foreground of one of the pictures, leaning up against a trailer home, something caught his eye — a cardboard cylinder, not quite 2 feet tall. It looked just like the barrel in which Willie’s body was found.

“Jesus Christ, man. That’s it right there,” he said to himself. “It was in their hands. They had it all along.”

The trailer belonged to a man who had lived in Happy Camp in the 1970s and whom everyone knew as Sonny. He washed trucks for a local logging company and lived on the owner’s property. Cook told police he had been on that property with Willie the day of the kidnapping, which is probably why the deputies photographed the area.

When Shelton went back to Happy Camp to learn more about Sonny, he discovered he had been arrested less than a year after Willie’s body was found, when a 5-year-old boy told his parents that Sonny had sexually abused him. The boy’s family had owned the logging company, and Sonny had been their employee. Prosecutors didn’t file charges, and Sonny was released.

According to documents Kayfetz filed with the court, the boy, who was in his late 30s when Nelson was arrested, had always wondered about the connection between Willie’s murder and his own abuse. His grandmother once told him she believed the cardboard barrel had come from their family’s property — she said it was a container for the detergent that Sonny used to wash the trucks.

The Happy Camp Big Foot statue on Dec. 13, 2024. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

The Happy Camp Big Foot statue on Dec. 13, 2024. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

First: A view down Washington Street in Happy Camp on Dec. 13, 2024. Last: Buildings on 2nd Avenue in Happy Camp on Dec. 13, 2024. Photos by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

He had recently searched for the Cook case online and was surprised to find that it had been reopened and that Nelson had been charged with the crime. He wondered: Did the police know about Sonny?

The local press had published a phone number for the Siskiyou detective’s bureau, urging people to come forward with relevant information about the crime. He called and left a message, but no one called him back. He called a second time and explained to a receptionist who he was and why he was calling. He was still waiting for a reply.

Sonny did eventually go to prison for sexually abusing a child. A mother reported him to the police when she learned he had been molesting her son for years. She told investigators that after Sonny was sentenced, other boys came forward to say he had abused them as well, according to a statement filed in court. He died in 2001.

To Shelton, these discoveries seemed like “a game changer.” He shared the details with Kayfetz. “I was like, ‘This is done,’” he said.

But the jury would not get to see the photo of the barrel or hear from Sonny’s accusers. The prosecution fought to exclude the evidence, arguing it didn’t prove Sonny had ever met Willie, let alone had kidnapped and killed him. And the judge agreed.

“It never even made it to court,” Shelton said. “Our job was to create reasonable doubt. We never planned to solve this case and figure out who did kidnap Willie. But I think we did, and no one cared.”

The case would radically alter Shelton’s beliefs about the justice system and his perception of how police and prosecutors operate. “I used to be on their team,” he said. “And when I worked for the defense I started to see that, you know, sometimes it’s more about winning than actual justice.”

He began to view his job as “quality control” for law enforcement agencies.

“Some district attorneys are wonderful and they disclose everything,” he said. “They’re not all like that. And so, if you’re a defendant and you draw a dishonest attorney, well, is that it? Is your fate sealed?”

It would be, Shelton said, if you didn’t have anyone to look into your side of the story.

***

Over the past 20 years, California has introduced ambitious legislation aimed at reducing incarceration, earning the state a reputation as a leader in criminal justice reform. But those efforts are routinely undermined by California’s failure to provide defendants with a proper investigation of the charges against them.

“That’s what’s so shocking — that it’s California,” said Goel, of the Sixth Amendment Center. “There’s perception, and then there’s reality. When will the state look in the mirror and see what it really is?”

Investigations affect every part of the criminal justice process. They’re not just about figuring out whether a client is innocent. Even if a case is moving toward a plea deal, an investigation can turn up information that forces a prosecutor to reduce the charge or compels a judge to grant bond or shorten a prison sentence.

Lawyers are discouraged from interviewing witnesses on their own. If a witness later changed their story or disappeared before trial, the attorney might have to testify on their client’s behalf and recuse themself from the case.

California lawmakers are considering a bill that could bolster defense investigations by eliminating flat-fee contracts. But it faces opposition from county officials, who say it would force them to increase their defense budgets without helping them pay for it.

New York was once very similar to California. Its counties managed their own public defender systems, without much input or funding from the state, until a class-action lawsuit, settled in 2015, led to statewide changes.

New York created an office tasked with improving public defense, eventually giving it some $250 million to dole out each year. Counties that take the money must prioritize certain aspects of public defense, including investigations. In a recent report to the agency overseeing the effort, these counties consistently said the ability to investigate cases was among the most profound impacts of the new funding. Some described specific cases that ended in acquittal or significantly reduced charges as a result.

California was also sued over claims it failed to provide competent defense. To settle the lawsuit, filed in Fresno County, Gov. Gavin Newsom in 2020 expanded the scope of the Office of the State Public Defender, which had previously handled death penalty appeals, to include support and training for county-based public defender systems.

But the governor committed only $10 million in one-time grants to the effort, and that money has since run out.

***

Nelson’s trial began in September 2009. The case hinged on Marshall’s account and Nelson’s confession. Kayfetz built much of the defense on what Shelton had discovered.

The jury deliberated for six days and could not come to a decision. Seven jurors believed Nelson was guilty of murder, and five did not. Six believed he had kidnapped Willie, the other six did not. The judge declared a mistrial. A few weeks later, Andrus, the district attorney, announced he was dismissing the charges against Nelson and his sister-in-law, whose kidnapping case was awaiting trial.

In a press release, Andrus said it was “the most difficult and painful decision I have made in my professional career.” He told a news reporter that his office had a heavy caseload and didn’t have the staff to prosecute the case. Andrus noted that he could always refile the charges if new evidence emerged or a new witness came forward.

Nelson was released, but he didn’t get to go home. He had to answer for the drugs he had on him at the time of his arrest and was sent to a Humboldt County jail.

“I left here just to be interviewed, and 16 months later I got out,” Nelson said from his home in Hoopa. “They got their hook in me, and they kept it in me. There’s nothing you can do when you’re in that situation.”

Gregory Nelson in his home in Hoopa on Dec. 13, 2024. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

Nelson said he’s certain he would be in prison if not for Shelton. “He believed what I told him,” he said. “Without that investigator, you don’t have a chance.”

Marshall and his mother have since died.

Shelton retired from defense investigation last year. He was initially hesitant to talk about the Nelson case and insisted that he had only been doing his job. He said he doesn’t want to be the hero of a story that is still, at its core, a tragedy. “Imagine being Bill Cook,” he said.

Although CalMatters was unable to reach Willie’s parents, a Facebook group dedicated to his memory, which has been inactive since 2016, includes posts from family members who express the belief that Nelson is guilty.

That’s what compounds the tragedy of the case for Kayfetz.

“They took a decades-old bandage off of these people’s hearts and just ripped it off,” she said. “It’s every kind of miscarriage of justice.”

Last year, the Siskiyou public defender’s office finally got its first staff investigator. Kayfetz said she needed to “clone him.” She cobbled together funding from a couple of new grants to hire a second, who started earlier this year. But she said it’s still not enough.

The Nelson case, she said, “rose and fell on the quality of the investigation.”

For his part, Andrus said he doesn’t believe Shelton’s work had much impact on the case. He said the prosecutors and sheriff’s deputies had always known that Marshall was “a compromised witness.”

“There were so many nails in the coffin of Steve Marshall’s credibility that it didn’t need more,” he said. “He was not the kind of person that we would want to rely on in a murder case.”

He said they had a duty to “look into his statement, see if we can corroborate it.” And Nelson had confessed. The other evidence they gathered, he acknowledged, “was not very strong.”

They pushed the case forward anyhow.

How we reported on California’s lack of public defense investigators

To report and write this story, CalMatters reviewed police reports, case files and other materials related to the kidnapping and murder of Willie Cook and the subsequent case against Gregory Nelson. We spoke with more than 45 people and made an effort to interview everyone who is named in the article. Some people have since died, could not be reached or declined our invitation. To quote people we could not speak with directly, including Bill Cook, Steve Marshall and Marshall’s mother, we relied on transcripts from recorded interviews with law enforcement.

CalMatters also analyzed staffing data, incarceration rates and caseloads for California’s 58 counties. We obtained this data from the California Department of Justice, the Judicial Council of California and the Vera Institute of Justice, as well as from court records.

OBITUARY: Rhoda Marilyn (Schactman) Bartels, 1935-2025

LoCO Staff / Thursday, June 5, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Rhoda was born on November 10, 1935, in Newark, New Jersey, to Joseph and Anna (Goldis) Schactman. She and her older brother, Barry, grew up there spending many memorable summers at Bradley Beach. Anna worked in a bakery, while Joseph was a long-distance truck driver. Rhoda attended Weequahic High School and was a passionate baseball fan, frequently taking the long bus ride to watch her beloved Brooklyn Dodgers. At age 14, she became president of the Jackie Robinson Fan Club and proudly collected many photos with her idol. In 1950, when The Jackie Robinson Story premiered, Rhoda had the honor of riding on the parade float next to him. After high school, Rhoda trained as a nurse’s aide, but the emerging beatnik scene in New York City called to her musical and artistic spirit. A devoted jazz lover, she often went out to see and mingle with legends like Miles Davis, Billie Holiday and Charlie Parker.

While working summers in the Catskills, Rhoda met and married Barry Bartels. Together, they had a daughter, Jennifer. In the mid-1960s they divorced, and Rhoda and Jennifer moved to California. She gravitated toward the Haight-Ashbury district of San Francisco, where her beatnik roots blended easily into the rising hippie culture. She encouraged many East Coast friends to join her in Northern California, including her longtime love, Charlie Provino. In 1969, while living at the Red House in Forest Knolls, Rhoda welcomed her second daughter, Rosychan.

Rhoda was a lifelong spiritual seeker and an avid reader. She practiced tai chi in Panhandle Park in the Haight for many years, she studied tarot, astrology, and Transcendental Meditation. In the early 1970s, as part of the back-to-the-land movement, Rhoda and Charlie bought property in rural Humboldt County and became farmers, living off the land in their rustic home in Harris.

Always a traveler at heart, Rhoda — with her youngest daughter in tow — spent much of the late 1970s and 1980s on a series of adventures. Her journeys included several years on The Farm, a commune in Tennessee; two stints living in Ibiza, Spain; and travels through Morocco, Jamaica, Belize, Guatemala, Amsterdam, Portugal, India and countless trips to Mexico. Despite her many travels, Rhoda always considered Humboldt her true home, where she lived a self-sufficient, off-the-grid lifestyle and faced adversity with grit and resilience. She survived CAMP in 1984 — and had the T-shirt to prove it. During the 1990s and 2000s, Rhoda blended her love of music and travel by spending winters in San Blas, Nayarit, Mexico, where she brought her keyboard and guitar to perform in local restaurants. Her sets featured jazz standards, blues, Beatles classics, and favorites by Bob Dylan and Janis Joplin.

At 64, Rhoda took up martial arts, studying with Dragon Heart Tang Soo Do and earning her black belt at 68. She went on to win awards in her age group at competitions in Costa Rica and became a favorite of Grandmaster Shin. While farming remained Rhoda’s passionate vocation, her compassionate heart and healing spirit also led her to study Thai Massage in Thailand, and in 2006, she became a Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA). Rhoda lived life fully — and on her own terms. She was adventurous, brave, generous and blessed with a wickedly sharp sense of humor. Whenever she tossed out a one-liner, there was a twinkle in her eye.

In her later years, Rhoda — affectionately known as Bubbe — was lovingly cared for in Arcata by her youngest daughter, Rosy, and her great-granddaughter, Alia. There, she enjoyed many sweet years filled with music, books, storytelling and laughter. Rhoda passed peacefully with her children by her side on March 3, 2025

Rhoda is survived by her daughters, Jennifer Kurtz and Rosy Provino; her surrogate daughter Melissa (Didi) Hall; her niece, Amy Schactman; her beloved grandchildren, Julian Kurtz, Paulina Agrawal, and Karina Provino; and her great-grandchildren, Alia Provino and Anaya Agrawal.

The family extends heartfelt thanks to Hospice of Humboldt, as well as all the friends and caregivers who lent their support.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Rhoda Bartel’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.