OBITUARY: John Dennis Wentworth, 1950-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, April 29, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

John

Dennis Wentworth passed away peacefully at home on April 7, 2025.

Dennis was born on May 3, 1950, in Willits. He and his brother Robert

were fraternal twins and shared many childhood memories. His parents

were John and Bernadette Wentworth.

After his family moved to Eureka, Dennis graduated from Eureka High School, class of 1969. He made many lifelong friends during his high school years. After high school, Dennis joined the Navy and was trained as a cook. He was assigned to submarine duty and spent time in the Pacific and off the coast of Vietnam.

After returning home, Dennis sharpened his cooking skills working at Angelo’s Pizza, where he was the manager. Looking to increase his income, Dennis then began working for various car dealerships in Eureka. His outgoing personality suited him well in this profession. Looking for more independence, he started his own business, “Mow and Blow Lawn and Tree Service,” which he worked at until his health started to fail. In his younger years he had a passion for surfing with his buddies Mike Niekrasz and Mike Coropassi. Sometimes his lawn business was put on hold as he and his friends snuck off to surf.

Later in life Dennis took up sailing. He became very competitive racing in Humboldt Bay, Whiskeytown, Lakeport and Big Lagoon. He was a member of the Humboldt Bay Yacht Club and served as the Commodore.

Dennis leaves behind the mother of his two boys, Sally Schick, his wife of 24 years, Dorothy Wentworth, sons Tyler (Amber), Jason (Brittany), his foster daughter Reanna, his stepsons Jeff and Nick Comer, as well as 18 grandchildren.

He was predeceased by his brothers Robert and Larry Wentworth as well as his parents John and Bernadette Wentworth. The family would like to extend a special thank you to Hospice of Humboldt who provided wonderful care and support in his final days. A thank you also goes out to his care provider, Eslys Salazar, and the local veterans network, who provided support.

There will be a memorial service at the Elks Lodge on Herrick Ave. June 8, 2025, from 1 to 3 p.m.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of John Wentworth’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

BOOKED

Today: 9 felonies, 10 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Yesterday

CHP REPORTS

Elk River Rd / Westgate Dr (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Amazon Warehouse Seen as Potential Revenue Lifeline in Tight County Budget

RHBB: This Valentine’s Day, Keep the Love Flowing — Not the Outages, says PG&E

OBITUARY: Jim Byford Jr., 1964-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, April 29, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Jim Byford Jr. was born to Cecelia (Fraley) and Jim Byford in Fortuna. He

grew up in Fortuna and was the youngest of three siblings.

While growing up in Fortuna he connected with many people, making lifelong friends. They made many memories together on Perras Court.

After he graduated highschool he moved to Yreka to help his mom take care of his Grandma Mary. He was always ready to lend a hand. While he lived there he had two children with Theresa (Pannell) Howard. His oldest was Jim Byford III (Sonny) and the youngest was Emma (Byford) Bal.

He touched many lives in Siskiyou County. He was a bus driver, an ice truck driver, and also worked at Nor-Cal. He had a twisted sense of humor and always said what was on his mind. You knew he was in the room by his boisterous laugh.

Later on he moved back to Fortuna. He was able to reconnect with many of his old childhood friends as well meeting many new people.

He was a hard worker right up until his death. In his spare time he would ride motorcycles with his many friends and family. He also enjoyed taking walks with his dogs at the old airport. His dog “Bean” went everywhere with him.

He is preceded in death by his mother, Cecelia (Fraley) Johnson, his father Jim Byford, his sister Nancy Byford, his grandchildren Kyle, Leeann and Trianna. He is survived by Jim Byford III (Sonny), his wife Danielle, their children Emilee, Kaylah and Jaxson, Emma Bal, her husband Sam and their children Xyla, Willow, Nancy and River, his sister Elizabeth Pitek, her Husband Mike and her children.

His celebration of life will be held on May 4, 2025 at the Fortuna Veterans Memorial building from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jim Byford’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: David Wayne Smith, 1943-2025

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, April 29, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

David

Wayne

Smith,

age 81, passed away on April 17, 2025, in Ferndale.

He was born on August 12, 1943, in Albany, New York, to Albert A. Smith and Martha V. Welter, and was preceded in death by his parents and his sister, Carrol E. Smith (Earl).

David was formerly married to Deb Oliver. He had no children, but is survived by his nephew, Scotty Smith Jenkins.

David had a remarkable and diverse career. He was a NASA engineer and was involved in the Apollo program. Beyond his work with NASA, David also had a significant impact in the music industry as an audio engineer, collaborating with numerous iconic artists such as Billy Joel, Black Oak Arkansas, Lionel Richie, B.B. King, Ray Charles, Journey and so many more.

Later in life, he also shared his love of music as a radio DJ, audio engineer, and program manager for KMUD in Humboldt County. David was also a natural inventor, always exploring new ideas. In his leisure time, David enjoyed soaking up the California sunshine and loved getting a good tan and cruising in his convertible.

David will be remembered for his brilliant mind, his passion for music and innovation, and his kindness towards others. Though a private man, he was always supportive and shared his knowledge generously with those around him. There will be no formal services held.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of David Smith’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

A Major Cascadia Zone Earthquake Could Cause Much of Coastal Humboldt to Rapidly Drop Into the Sea, New Study Finds

Ryan Burns / Monday, April 28, 2025 @ 4:29 p.m. / Environment , Science

Humboldt and Arcata Bay during a 2021 king tide. | File photo by Tim Hanan.

###

Those of us who live in earthquake country tend to have two primary anxieties about the unsettling events: the shaking itself (collapsed roofs, crumbling buildings, etc.) and a tsunami (giant wall of water, ‘nuf said). However, a newly published study invites us to adopt an altogether new earthquake-related fear: rapidly sinking land.

The study, published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), found that a major earthquake along the Cascadia subduction zone will likely cause between 1.6 and 6.5 feet of sudden subsidence long the Washington, Oregon and northern California coasts.

This abrupt land sinkage would dramatically raise the relative sea level of coastal communities in a matter of seconds. In the worst-case scenario, the subsidence would more than double the flooding exposure of coastal residents, structures and roads. And those risks would remain long after the shaking settles.

“This lesser talked about hazard is going to persist for decades or centuries after the earthquake,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Tina Dura, told NBC News. “The tsunami will come in and wash away and it’s going to have big impacts, don’t get me wrong, but the lasting change of the frequency of flooding … that’s going to have to be dealt with.”

Such damaging events have already happened elsewhere on the globe. Earthquake-driven coastal subsidence followed recent earthquakes in Chile, Alaska, Southeast Asia and Japan, resulting in such severe consequences as permanent land loss, widespread infrastructure damage and forced relocation.

These risks are exacerbated by climate-driven 21st century sea-level rise. In some communities along the coastal Washington, Oregon and northern California, the effects of sea-level rise are somewhat moderated by gradual coastal uplift. In fact, coastal uplift rates exceed the current rate of sea-level rise in such places as Astoria, Ore., Port Orford, Ore., and our neighbor to the north, Crescent City.

Humboldt Bay residents aren’t so lucky. Here, the study’s authors note, “complex regional tectonics are causing gradual subsidence, resulting in the highest recorded Pacific-coast RSLR [relative sea-level rise] rate of 4.7 [millimeters per year].” In other words, the ground beneath our feet is slowly dropping as the water rises.

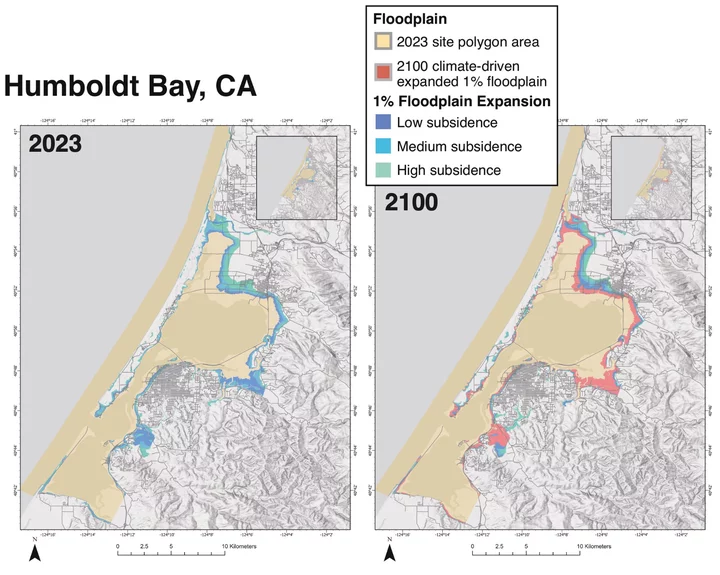

Floodplain map and bar graph depicting the expansion of the 1% floodplain (an area with a 1-in-100 chance of flooding each year) after earthquake-driven subsidence today (2023) and in 2100 when the earthquake-driven subsidence is amplified by climate-driven sea-level rise for Humboldt Bay. The bar graph shows the amount of land area, number of residents, structures, roads, and different land-use types in the 1% floodplain following earthquake-driven subsidence today (2023) and in 2100, when the effects of earthquake-driven subsidence are amplified by climate-driven sea-level rise. | Creative Commons license CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0.

###

The study defines a “major earthquake” as a magnitude 7.7 to 9.2, and while that may sound unlikely (knock wood), scientists were able to discover how often they occur by radiocarbon-dating plant fragments preserved within pre-earthquake peat or overlying mud. The results? There have been 11 such “great earthquakes” along Cascadia’s coasts over the past 6,000-7,000 years. They hit roughly every 200 to 800 years.

The most recent “great earthquake” along the Cascadia subduction zone struck in 1700 — more than 300 years ago. The CSZ is a major offshore fault line running from Northern California to British Columbia.

The authors of the new study warns that coastal flood hazard analysis often overlooks the risk of sudden earthquake-triggered land subsidence.

“This study underscores the need to consider combined earthquake and climate impacts in planning for coastal resilience at the Cascadia subduction zone and globally,” it says.

The combined effects of earthquake subsidence and climate-driven sea-level rise could more than triple the flood exposure of residents, structures and roads in the next 75 years, the study found. The coastal areas at risk are home to airports, major highways, wastewater treatment facilities, businesses and homes.

County leaders recently completed a Sea-Level Rise Adaptation Plan for Humboldt Bay/Eureka Slough Area. It advocates “an incremental approach” to planning, using various “shorter-term actions” to reduce immediate risk and buy time for more ambitious “longer-term actions” to address future conditions. It does not appear to contemplate the possibility of long-term projections becoming a reality all at once.

Tsunamis along the Cascadia Subduction Zone can be triggered in a mega earthquake when the Juan de Fuca plate is rapidly pushed underneath the North American plate, displacing massive amounts of water. That same movement can cause coastal land to suddenly drop, according to Dura, an assistant professor in geosciences at Virginia Tech.

If that happens, she recently told the San Francisco Chronicle, “All the sea-level rise you expected by 2300 is going to happen in minutes.”

You can download the study and read it for yourself via the link below. The study was funded by the Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Center, part of the National Science Foundation.

###

###

NOTE: This post was updated on April 29 to add the maps and bar graphs.

Does Your Dog Need Her Rabies Shot? You Can Get it For Her on the Cheap at One of These Upcoming Clinics

LoCO Staff / Monday, April 28, 2025 @ 3:19 p.m. / Animals

Photos via Pexels.

Press release from the Humboldt-Del Norte Veterinary Medical Association

The Humboldt-Del Norte Veterinary Medical Association is sponsoring a county-wide low-cost canine rabies vaccination clinic. The Humboldt-Del Norte Veterinary Medical Association offers these low-cost canine rabies clinics as a public service.

It is important that all dogs and cats be vaccinated, as we have had several cases of rabies in wildlife and pets in Humboldt County as recently as the last few months. Foxes, skunks, and bats are a few examples of rabies carriers. We will be vaccinating dogs at the cost of $10.00 per rabies vaccination.

Other canine and feline vaccinations will be available. The costs of these vaccines will vary with the clinic.

If you have any questions, please contact the animal hospital you would be interested in taking your pet(s) to.

Clinic Schedule:

- Thursday, May 1, 8 a.m.-5 p.m.: Sunny Brae Animal Clinic Saturday

- Saturday, June 7, 8 a.m.-1 p.m.: Myrtle Ave Veterinary Clinic

- Thursday, July 17, 8 a.m.-noon: Arcata Animal Hospital

Additional clinics are available in Trinity County. Please call for dates and times.

Sincerely,

Julie Lisignoli, RVT

The Celebrity Guests for This Year’s Forest Moon Festival Have Been Announced, And You’ll Never Guess Who’s Coming to Town!

LoCO Staff / Monday, April 28, 2025 @ 12:39 p.m. / Our Culture

You know these guys. From left: a Rebel Force Radio host, the other Rebel Force Radio host and Kyle Newman. Photo courtesy the Humboldt Del-Norte Film Commission.

Press release from the Humboldt-Del Norte Film Commission:

The 3rd Annual Forest Moon Festival returns this May 30th–June 1st, 2025, hosted by the Humboldt-Del Norte Film Commission. Taking place across the iconic redwoods of Northern California — the very filming location for the Forest Moon of Endor — this immersive, multi-day celebration will span both Humboldt and Del Norte counties with events for fans of all ages.

This year, the Forest is especially strong with the guest lineup, including Kyle Newman, director of Fanboys and a beloved voice in the Star Wars community, and the team behind Rebel Force Radio, one of the largest and internationally popular Star Wars podcasts, Jason Swank and Jimmy “Mac” McInerney. Their presence promises a weekend filled with galactic insights, unforgettable conversations, and deep dives into the franchise and fandom. Attendees can catch them at exclusive appearances throughout both Humboldt and Del Norte Counties, making this a truly unforgettable Forest Moon Festival.

From costumed appearances by Lucasfilm-approved fan groups, to rebel training courses, a scavenger hunt with epic prizes, and late-night afterparties, the weekend will be packed with interactive and family-friendly experiences. Free movie screenings will also take place in Fortuna, Eureka, and Crescent City.

The full schedule goes live this week, with new events being added in the weeks leading up to the festival. Be sure to check back often! Fans are encouraged to attend in costume and show off their galactic best — just visit the website for guidance on costume policy and safety tips.

Starting May 3rd, the Forest Moon Exhibit at the Redwood Coast Museum of Cinema in Eureka (235 F Street) will be showcasing the region’s part in Star Wars history. The exhibit also features original memorabilia and insights into becoming a certified Lucasfilm costumer.

For all details, maps, and up-to-the-minute updates, visit www.forestmoonfestival.org and download the Redwood Coast Film Experience App on iOS or Android as well as follow on social media at @forestmoonfestival.

The Forest Moon Festival is made possible through support from the Humboldt Lodging Alliance, Measure J, County of Humboldt, and County of Del Norte, with special thanks to the cities of Fortuna, Eureka, and Crescent City for co-hosting events.

This guy seems to show up for every Forest Moon Festival. Last year proved that he’s not such a bad dude by posing for selfies at the Arcata Farmer’s Market. Awww! Photo: Mark McKenna.

In Gargantuan-Number-to-One Odds, This Husband and Wife Both Served on the Same Eureka Jury This Month

Dezmond Remington / Monday, April 28, 2025 @ 7:21 a.m. / Community

David and Tori Wilmington.

There are about 136,000 people living in Humboldt County, according to the 2020 census, and about 106,000 of those people are adults. A few hundred of them will get a little white and red card in the mail during any given year telling them it’s time to sacrifice a little time out of their lives and serve on a jury, and many will have some kind of excuse and get out of it. Quite a few others will simply ignore the summons. Many of those that do show up will be excused.

When the process is concluded, 12 people (about 0.00009% of Humboldt’s population) will be chosen for jury duty, statistically a tiny slice out of a county that’s larger than Rhode Island and Delaware combined — so it’s incredible that this month, a husband and a wife from Eureka served together on the same jury.

“The judge asked me ‘Do you know anyone else here in the courtroom?’” said Tori Wilmington, 47. “And I was like, ‘Well, yes,’ and he said, ‘OK, who do you know?’ and I said, ‘My husband, the juror in the back!’ And he was like ‘That’s never happened to me before,’ and the lawyers are looking at him too. ‘It’s never happened to us either!’”

It’s a pretty extraordinary coincidence that she, and her husband of 15 years David Wilmington, 53, both served on a drunk-driving trial. Both David and Tori wanted to make it on the jury, but for Tori it was especially exciting because she had always wanted to serve on a jury. She had been impressed on the importance of community service since a young age by her grandmother, and it left a mark on her.

She was thrilled to be summoned when she was 28, but she had recently given birth and missed the selection. This time around, she was happy to be there and the experience lived up to her expectations.

“I know [most people want to avoid jury duty],” Tori said. “But I look at it like this: if I were ever to need to have a jury of my peers, I would want to know that not everybody sitting there hated every second of theirs; that they were actually going to pay attention, and that they were going to be interested in what was going on and be able to give me a fair shot.”

David, who had served on a few juries before this, wasn’t as psyched, but he enjoyed the experience of working together with his wife.

“Being with her means I don’t always snap so quickly to stand my ground, per se,” David said. “You’re gonna have disagreements. We always do, because we view things through different lights, and you have to learn to, frankly, shut up for a few minutes to absorb what information you’ve just got, rather than just let the emotional response happen.”

Both he and Tori would love to get a chance to repeat the experience, even if the chances of that happening are millions to one.

“You know, out of all the things that we’ve gotten to share over the years, this was just a really cool thing to be able to do together,” Tori said. “We’ve done other community service things together, so in a way, it didn’t totally shock me. We’ve always given blood together. We were Cub Scout leaders together. Serving our community together is not something new for us. This was just a different way for us to serve our community together. It was just a little surprising.”