Extradition Arrest Warrant Issued for Out-of-State Asshole Who Keeps Threatening Local Schools

Isabella Vanderheiden / Friday, March 21, 2025 @ 3:57 p.m. / Crime

PREVIOUSLY:

- Multiple Humboldt County Schools Placed on Lockdown Due to Threats

- LOCKDOWNS UPDATE: Out-of-State Man Identified as Suspect Believed to Have Made Threatening Calls to Multiple Humboldt Schools and Businesses

###

An extradition warrant has been issued for the out-of-state individual who is believed to be responsible for a string of threatening phone calls to Humboldt County schools. The threats, which have been deemed non-credible by local law enforcement officials, have prompted lockdowns at several local schools. Just today, Arcata High School, Coastal Grove Charter School, Pacific Union Middle School and Jacoby Creek School were put under a brief lockdown.

“We are in contact with Arcata Police [Department], who do not think the threat is credible,” Arcata High School Principal Kristin Ferderber wrote in a statement issued to parents early this afternoon. The school directed students and staff to “shelter in place” while APD investigated the threat. The lockdown has since been lifted.

In a press release issued Wednesday afternoon, local law enforcement said they were able to track down an out-of-state adult male suspect who’s believed to have phoned in threats to “over 20 schools and businesses” since January.

Reached for additional information this afternoon, Arcata Police Chief Bart Silvers confirmed that the threats made today appear to be from the same suspect. “A local full extradition arrest warrant has been issued and sent to the out-of-state agency for service,” Silvers wrote in an email to the Outpost. “We are currently working with them to locate and apprehend the suspect.”

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 17 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 6

CHP REPORTS

Us101 N / Humboldt Hill Rd Ofr (HM office): Roadway Flooding

5859 MM101 N MEN 58.60 (HM office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Crash Blocks Lane on Northbound U.S. 101 at Humboldt Hill Onramp

RHBB: Crash off 101 into Trees North of Willits

Study Finds: When Moths Freeze: How LED Streetlights Are Silencing the Night

High Country News: Trump’s call for deep-sea mining off Alaska raises Indigenous concerns

Cockroaches Have Set Up Shop in Arcata’s Fourth Street Market, Humboldt County Division of Environmental Health Alleges

Hank Sims / Friday, March 21, 2025 @ 2:43 p.m. / Health

Photo: Google Street View.

A health inspector descended upon Arcata’s Fourth Street Market today. This health inspector did not care for what they found.

Their inspection report states:

Observed cockroach droppings, dead cockroach bodies and two (2) live adult German cockroaches in deli cabinet. Increase cleaning, vermin-proofing and professional pest control efforts to exclude insects from the facility.

…

Due to active cockroach infestation, this facility is closed and permit suspended by this office.

Food preparation at the market is off, for the time being. No poor boy sandwiches for you.

Fourth Street has the ability to appeal the inspector’s ruling. The entire health inspection report can be found at this link.

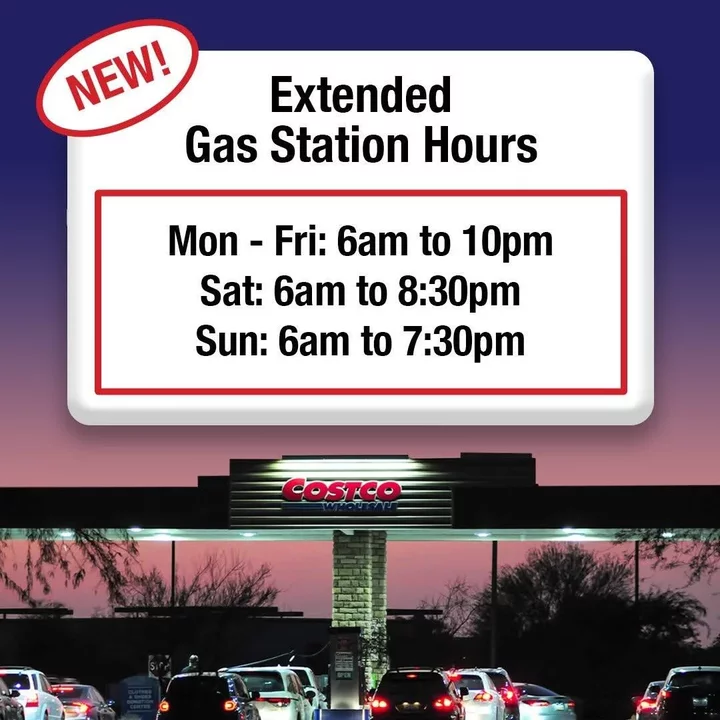

The Costco Gas Station in Eureka is Now Open Longer Every Day

Ryan Burns / Friday, March 21, 2025 @ 2:12 p.m. / Business

Eureka’s Costco gas station, at 1006 West Wabash Avenue, is now available for self-pumping both earlier and later. | Google Street View.

###

Good news, frugal motorists! Costco has expanded the hours of operation for its company gas stations across North America, including the pumps here in Eureka.

The new open hours are 6 a.m. to 10 p.m. Monday through Friday; 6 a.m. to 8:30 p.m. on Saturdays; and 6 a.m. to 7:30 p.m. on Sundays. That gives drivers an extra 25 hours per week to gas up, compared to the station’s previous hours.

Will the lines be any shorter with all this extra time to refuel? Let’s hope so! Costco still routinely has the cheapest prices per gallon in the county, excluding a couple of tribe-owned stations. It’s currently the only station in Eureka selling regular unleaded for less than five dollars per gallon (by one tenth of a penny, but still).

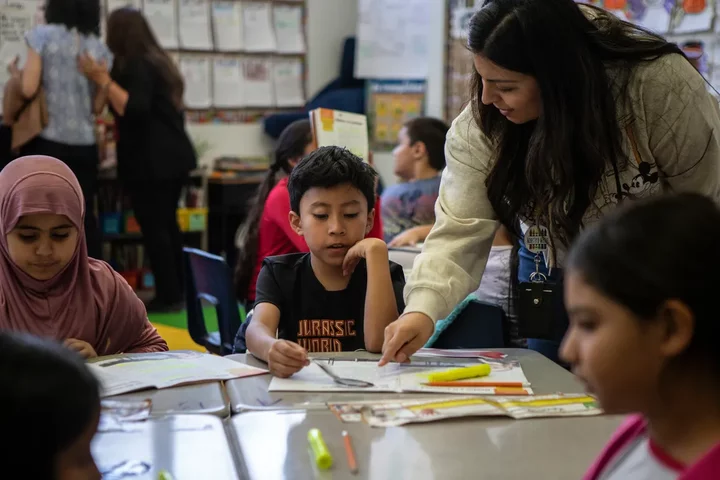

Parents Can’t Figure Out How California Schools Are Doing. Newsom’s Plan to Fix That Stalls

Adam Echelman / Friday, March 21, 2025 @ 8:56 a.m. / Sacramento

Students at Washington Elementary School in Madera on Oct. 29, 2024. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters/CatchLight Local

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

In his first year as governor, Gavin Newsom made the creation of a comprehensive, statewide education data system one of his top priorities, but its debut is behind schedule.

In 2019, he launched the Cradle-to-Career Data System, a multi-year initiative to collate data from preschools, K-12 districts, colleges and job training programs, culminating in a series of public dashboards that track students’ progress. A few years later, during his 2022 re-election campaign, “cradle to career” was the tagline of his education platform.

“This was a signature initiative by the governor,” said Alex Barrios, the president of the Educational Results Partnership, an education data nonprofit. “You’d think taxpayers would be asking: “Where is this thing?’”

The Cradle-to-Career team initially said the public would have access to some of the data by the spring of 2024, mostly through a website that would show the progress of specific school district students through college and their first few years of employment. Later, the Cradle-to-Career team updated the timeline to say that the data would be publicly available in the fall of 2024. Now, Angelique Palomar, a spokesperson for the data project, said the first data dashboard will be publicly available “this spring,” though she did not specify a date.

Palomar said the first stage of the project is nearly ready for release and that the delays stem from an abundance of caution regarding students’ privacy. For example, she pointed to certain populations, such as students in rural areas or certain racial/ethnic groups, which are so small that it’s easy to figure out someone’s identity. Federal law prohibits schools from sharing students’ personal data.

“We are prioritizing securing the data system, ensuring privacy protections, and providing linked information that is accurate and reliable before we can make our tools publicly available,” she said.

The state’s Department of Technology, which periodically reviews IT projects, says the Cradle-to-Career Data System needs “immediate corrective action” because of its delayed schedule.

Once it’s released, the Cradle-to-Career data system could reshape parents’ and students’ decisions and lead to significant policy changes. With this data, parents would be able to see the long-term college and employment results of their child’s local elementary school district. School and college counselors could provide more precise advice to students about their futures, and state programs, such as the under-utilized savings program CalKIDS, could use the data to pinpoint potential beneficiaries.

Lacking an adequate data system

Before the launch of Cradle-to-Career, California was “one of only a handful of states without a student data system that can answer important questions about the educational pipeline and the impact of education on work and earnings,” a report by the Public Policy Institute of California stated in 2018.

Kentucky’s data system already allows for that kind of analysis and is the “canonical” example of good education data, said Iwunze Ugo, a researcher with the institute. He acknowledged California’s progress since the 2018 report. “The Cradle-to-Career system in California is particularly notable for how ambitious it is.”

Since 2019, the state has allocated more than $24 million for the project. The Cradle-to-Career Data System became an official state entity, with a 25-person team, 21 board members, and two, 16-member advisory boards. Ugo pointed out that unlike other states, California has made “community engagement” a centerpiece of the data tool: The state embarked on a multi-year campaign, surveying communities in both Spanish and English across the state about potential uses and concerns with its data and the way it will be presented.

Cradle-to-Career has signed data-sharing agreements with 16 other state agencies, such as the California Department of Education and the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency, and processed over a billion data points about students’ education and workforce outcomes.

At a February board meeting, the Cradle-to-Career staff shared a progress report, outlining over 20 accomplishments, each with a check next to it. The only blank box in the checklist was the last one: officially launching the first data dashboard.

In his opening remarks, Cradle-to-Career Board Chairperson Gavin Payne didn’t acknowledge the delay — none of the board members did, overtly.

Mary Ann Bates, executive director of the Cradle-to-Career Data System, referred to the delay briefly in her remarks to the board, saying that her office is committed to releasing the first tranche of data and “looking at all options to hold the contractor accountable” for “some delays and lost time.” Asked by CalMatters to clarify the comments, Palomar, the spokesperson for Cradle-to-Career, said Deloitte is the contractor, but she refused to specify why it may be responsible for these delays.

Could the data be ‘used against’ school districts?

Although unprecedented in scope for California, many of the features of the Cradle-to-Career Data System aren’t new. The data already exists, albeit in some hard-to-find places, and some groups have already started working together to analyze shared trends.

Barrios’ nonprofit, the Educational Results Partnership, has received over $13 million since 2012 to help create and operate Cal-PASS Plus, which allows users to see how students from specific California high school districts perform at the college level. But Cal-PASS Plus is only available to researchers as well as school and college administrators, and most K-12 districts are not required to participate. Still, in any given year, Cal-PASS Plus has records from more than 70% of high school students in the state, Barrios said.

A mandatory data-sharing system, such as Cradle-to-Career, is harder to implement, he said. “School districts don’t want the data used against them.” For example, he said one fear is that residents and policymakers might blame a high school for a low college matriculation rate instead of working to improve it. Palomar said the current delays are not tied to any reluctance by school districts since the data already exists and is shared widely.

Barrios said his organization stopped operating Cal-PASS Plus a few years ago, in part because he assumed it would soon be obsolete.

“We walked away from all these things thinking the state was going to do it,” he said. “But that obviously hasn’t happened.”

OBITUARY: Brad Thorton, 1949-2025

LoCO Staff / Friday, March 21, 2025 @ 7:11 a.m. / Obits

Brad Thorton passed on to the great bar stool in the sky on St. Patrick’s Day, March 17, 2025. According to the legends, Brad was born in Quebec, Canada on November 17, 1949, which would have made him 75 at the time of his passing. He was a “regular” at the World-Famous Logger Bar and that is where I met him, when I bought the bar in 2022. He came with it. The fourth bar stool from the left when you entered the bar was Brad’s. Two pints of PBR and a bag of Cheetos was his go to. He was loved and treasured in the community.

Brad’s past has a mist and a mystery about it. As his friend Paddy said, “Brad never let the truth get in the way of a great story”. Or as his roommate (and the person who tried to save his life) Zach, said, “I’m not even sure that Brad was his real name”.

After a stint with the Navy Seals in Greenland, Brad did a brief tour with the Rolling Stones. He is credited with transforming their distinctive sound. He then moved to Washington D.C. where he started a farmers’ market. It was there, selling cabbages, that he met his good friend, V.P. Dick Cheney. He often alluded to some missions he did with Dick for the CIA. They involved golden domes and deserts, though we were never sure if he was in Saudia Arabia or South Bend, where the golden dome belongs to Notre Dame. (Brad played fullback for the Fighting Irish on their national championship team).

Always seeking new vistas, Brad moved into pharmaceuticals. Though he never had a driver’s license (not even sure if he was a citizen), he tooled around the country in his vintage T-Bird pioneering new distribution networks for the emerging pain management, opioid market.

Brad was also missing fingers. We were never quite clear what happened. But it could have involved a drunken bet with a friend over who would cut their fingers off first. Brad won.

Brad lived a full, intense and complicated life. We loved him here. This is a homage to Brad. I imagine him laughing. He had a keen sense of humor. Flights of angels sing thee to thy rest. There is a celebration of life for Brad every day at the Logger from 4 -6 pm - happy hour.

###

The obituary above was submitted by Michael Fields on behalf of the Blue Lake community. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Arcata’s Mobile Home Repair Project is Underway

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, March 20, 2025 @ 3:18 p.m. / Arcata

A picture taken in one of the to-be-repaired mobile homes in Arcata. Photo courtesy of the city of Arcata.

PREVIOUSLY

Arcata’s program to help mobile home owners repair their houses has begun.

The Manufactured Housing Opportunity & Revitalization Program (MORE) pays for mobile home repairs, if the homes are in a mobile home park and owned by someone making less than 80% of Humboldt’s median income. Contractors hired by the city do the work.

The program focuses on repairing violations of health and safety codes, as well as improving ADA accessibility.

Arcata announced the program last year after being given a $3 million grant to fund the project by the California Department of Housing and Community Development.

Arcata’s Director of Community Development David Loya gave an update at the city council meeting last night, highlighting some of the success the program has achieved. According to Loya, mobile homes are an important resource for people who don’t have enough money to buy a home or rent one, and this program is helping alleviate much of the burden on residents.

There were 46 applicants, 23 of which were funded. According to Loya, two of the issues repaired in two different houses were ceilings riddled with holes and a bathroom floor so spongy the occupants never filled the bathtub up out of fear it would collapse under them. There were, of course, plenty of mold-related issues to clean up as well, as well as electrical, plumbing and flooring snafus. Two homes were in rough enough condition that they qualified to be totally replaced.

The program will end in August of 2026, or when the money runs out.

“Thanks to the MORE program, Arcata will be able to repair this aging housing stock, increasing the amount of high-quality housing available in the city,” Loya said.

Nicholas Brichta, one of Arcata’s Community Development Specialists, did much of the legwork for the program. He told the Outpost he was glad that they were starting to fix up the homes that needed it the most.

Brichta also said that the program is still accepting applications, and encouraged people to apply, especially if their house was cited for a code violation.

“It’s been a lot of work making sure everything is set up correctly,” Brichta said. “There’s a lot riding on this program for people. It takes a while, but it’ll be worth it when it’s done.”

(AUDIO) Ike Sperling, Fourth Grade Spelling Bee Champ, Drops By KHUM to Celebrate the Big Win

Isabella Vanderheiden / Thursday, March 20, 2025 @ 12:54 p.m. / :) , On the Air

###

Jacoby Creek Elementary fourth-grader Issac “Ike” Sperling spelled his way to victory at the 40th Annual Paulette Gilliam Humboldt County Spelling Bee last month, beating out the competition with the correct spelling of continuum. In a couple months, Ike will head to the Scripps National Spelling Bee in Maryland where he will compete against 245 spellers from across the country. Let’s give it up for Ike!

The spelling aficionado and his dad, Steven Sperling, celebrated the big win with our very own KHUM DJ Toby this week during his morning segment “KHUM Kids.” In their interview, Ike describes his surprise when he realized competitors wouldn’t be separated into age groups.

“I started panicking,” Ike said, adding that last month’s competition was his first spelling bee. “Later on during the competition, I asked twice if it was going to be 4th through 8th grade just to confirm.”

Asked how he prepared for the spelling bee, Ike offered a no-nonsense response: “It’s simple — two words: I read.”

Click the link below for the full interview!