GUEST OPINION: As a Person Who Participated in the Demonstration Last Weekend, I Want to Thank the Eureka Police Department

Elle Penner / Wednesday, April 9, 2025 @ 10:35 a.m. / Guest Opinion

Photo: Andrew Goff.

To Chief of Police Brian Stephens and his fellow officers present at the Hands Off Protest:

I am reaching out to you to extend my personal thanks and heartfelt appreciation for your de-escalation efforts at the Hands Off protest on April 5, 2025 in front of the Humboldt County Superior Courthouse in Eureka.

At the time of the incident when your team’s intervention was required, I was still on site, though positioned on the steps close to the courthouse doors, filming the band that was playing there. As I turned away from the band and looked down on the street, it was clear that there was a commotion affecting traffic, with civilians in the street and a truck stopped with the driver having exited his vehicle, prompting you and your fellow officers to respond to a developing disturbance.

As someone who studied domestic and international social movements in my undergraduate years, I felt keenly aware of the risk of quick escalation of physical conflict in an amassed crowd setting. I grabbed my younger sister and got us away from the area as quickly and safely as possible. But in reviewing footage and published local articles concerning the play-out and outcome of that incident the next day, I felt relieved to learn how you and your team managed to separate parties, redirected folks not in vehicles off of the street, and got traffic moving again.

The actions of yourself and your team, I personally interpret to be actions that valued our community’s safety while also safeguarding citizens’ rights to assemble and to exercise free speech.

As a mother of a six-year-old daughter, I feel obligated to take my physical safety seriously — more so than before I had a child who needs to grow up with her mother there for her. However, as a social worker, I feel a responsibility to use my right to free speech to express solidarity for marginalized folks’ rights, whether they are children and families I serve, my neighbors, or mine and my daughter’s for that matter. For that reason, I was at that protest along with the two previous protests in Eureka. I hope to continue to safely protest at more in the future.

How you and your team handled things on April 5th encouraged me to feel affirmed to pursue my values and exercise my rights while still having good odds of coming home to my little girl.

Thank you for your service to our community last Saturday.

Kind regards,

Elle Penner

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 5 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Silkwood St / Hiller Rd (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Us101 S / Redcrest Ofr (HM office): Live or Dead Animal

1850 MM101 N DN 18.50 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Klamath-Trinity Joint Unified School District to Reopen Tomorrow

RHBB: Hoopa Valley Police Believe Suspects No Longer in the Area

RHBB: Suspicious Device Prompts Road Closure in Rosewood Neighborhood

Mad River Union: Plaza Grill restaurant reopening April 8

All Simulated Hell Will Break Out Around St. Bernard’s Today

Hank Sims / Wednesday, April 9, 2025 @ 9:07 a.m. / Non-Emergencies

The Eureka Police Department, via its Facebook, is promising lights, sirens, ambulances, people scurrying here and there and even helicopters sometime today, as the St. Bernard’s student body gets one of those dramatic scared-straight lessons about the dangers of drunk driving.

It’s gonna be one of those deals where everyone simulates a gory car crash right out in front of the school. One student will pretend to be decapitated and all the others will come by and gawk at paramedics as they struggle to sew her head back on. Cops will run this way and that, there’ll be some street closures probably, a grieving mother will wail to the heavens so that kids might be edified about the pain they inflict upon their families when they choose to drink and drive.

Don’t be alarmed. Let the kids have their fun.

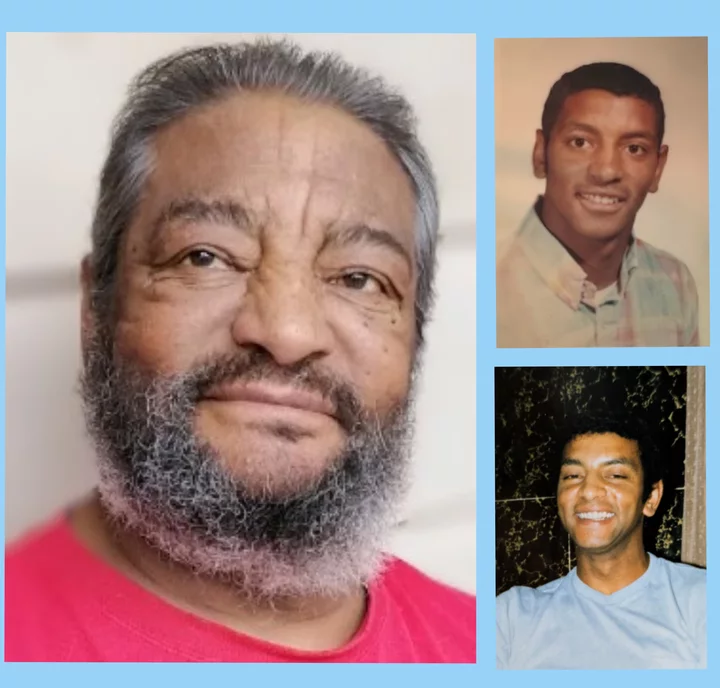

OBITUARY: Lawrence Carlton Landry, 1950-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, April 9, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Lawrence

passed away unexpectedly at home in Eureka on March 30, 2025, with

his partner Tina by his side. Over the past few years, he has had

many health challenges that he faced with bravery.

Lawrence “Larry” Landry aka “Pops” aka “Lar-Bear” was born in Lake Charles, Lousiana to Carlton and Victoria (Declues) Landry. His family heritage is Creole – a mixture of French, Black, and Native American.

In 1952, the family moved from Louisiana to Eureka. Larry attended local schools, graduating from St. Bernard’s High School in 1969. He was one of just a few black students integrating local schools in the 1950s and 1960s, and only the second black student to attend St. Bernard’s. He was an athlete, competing in wrestling (beating many of the best local wrestlers by his junior year), track and field, football and basketball. While at St. Bernard’s, he set the shot-put record that stood until 1997. When it was finally broken, Larry made a point to meet the young man who broke his record and shake his hand.

In his senior year at St. Bernard’s, he was in a production of Up With People – a musical entertainment group promoting multiculturalism, racial equality, and positive thinking through song and dance. In the early 1970s he played football at College of the Redwoods and boxed with the Eagles Athletic Club. Larry enjoyed riding motorcycles in his younger days and played city league basketball for a number of years.

He had a great love of music. Just a few days before his passing he was sitting in the sun on the porch, grooving to Percy Sledge.

Larry never met a stranger. Always friendly, always willing to lend a hand. He loved to laugh, especially with his family.

Larry worked at a variety of jobs over his lifetime – Hilfiker Pipe, Construction, Crestwood Manor, Commercial Fishing (on the Linda Ellen and the Gary Lee), Noel’s TV and Appliance, plus a bit of Humboldt County-style gardening 😊.

He helped Benny Gill with remodeling the Whaler’s Inn (now La Patria) in Fields Landing many years ago. His name, along with many others, is burned into the beam above the bar.

He was the first black commercial fisherman in Eureka. It was dangerous, tough work but he loved it. When he worked at Crestwood Manor, his caring and ability to work with psychiatric patients was legendary. When a staff member needed assistance, they didn’t just page for help, they paged for Larry.

Larry loved animals and had quite a collection over the years – birds, snakes, an alligator, rabbits, guinea pigs, chickens, ducks, geese, cats, fish, and many beloved dogs. He also loved rocks of all kinds. He enjoyed excursions to collect rocks and trips to Champman’s Gem and Mineral Shop. Chapman’s was a special source of joy for him in recent months. He enjoyed getting out in the community on his scooter with family. He took many scoot/walks all over Eureka with his son Lonyx.

Larry married twice – first to Donna (Borden) Landry-Rehling. That marriage blessed him with his son Lonyx Landry. Later he married Rosemary (Bulger) Landry. His beloved daughter Derixa Landry came from that marriage. He met Tina Moulton in late 1978. That union added three more very welcome children – Lenoxx, Victoria, and Lexus Landry. When Lexus was born, he was a stay-at-home dad for a while and made the comment “This is so fun, I want another one!” Tina quickly disabused him of that notion.

Larry’s children were everything to him. He was so grateful that all his children stayed close by, and he got to see them often. His children rose to the challenge as Larry’s health declined and we will be forever grateful for that. He was looking forward to his 75th birthday party in April.

Larry was predeceased by his parents Carlton and Victoria Landry, his brother Joseph Landry, his sister Gertie Mae (Landry) Bryson, his two infant brothers David and Anthony Landry, his great nephew Marcus Bryson, and his great niece Shyelynn Landry.

He is survived by his partner Tina Moulton, his ex-wives Donna Landry-Rehling (Bryan) and Rosemary Landry, his children Lonyx Landry (Kathy), Derixa Landry (Brad) Lenoxx Landry, Victoria Landry-Chesbro (Alan), and Lexus Landry. Also survived by his brother Alvin Landry (Raelene) and sister-in-law Vertie Landry, grandson Lyndin Landry, granddaughters Savannah “Bo” Risling, Lina Landry, and Nyexa Landry Brambani, nephews Garrick Bryson (Cecilia), Danny Landry, Michael Landry, Christopher Landry (Julia), nieces Cynthia (Bryson) Shelton (Mark), Cathy Landry and Crystal Landry, plus many many great nieces and nephews. Also missing him are his two Italian Greyhounds Madonna and Riot, and his grand-dogs Bisous, Bobbi Dazzler and Stuart Little.

The family wishes to thank everyone who helped care for him: Angela Smith NP, Kidney Care Services of Humboldt, Open Door Community Health, Providence St. Joseph both inpatient and outpatient services – Med Surg 2 you are all amazing; Fresenius Dialysis Center, Humboldt Medi-Trans, Humboldt County IHSS, Humboldt Bay Fire, City Ambulance, EPD and Ayers Family Cremation.

A special thank you to St. Joseph Providence Pet Therapy Program teams Allan Wiegman/Kiya and Jeanne Sapunor/Otis for therapy dog visits while Larry was in the hospital – you brightened his day. His one complaint about the hospital was that there weren’t any dogs!

A Celebration of Life will be held at Eureka Woman’s Club, 1531 J Street, Eureka on Saturday May 3, 2025. beginning at 3 p.m. For questions, please reach out to one of Larry’s children.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Larry Landry’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Carmelo Flory Gamaza, 1949-2025

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, April 9, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Carmelo Flory Gamaza (“Venezuela”)

January 22, 1949 - April 1, 2025

Carmelo Gamaza, known to most of his friends as “Venezuela,” passed away suddenly in his Arcata home on April 1st in the company of his dear friend and caretaker, Arleeth Torres.

Carmelo was born in Caracas, Venezuela and as a young man traveled the world, throughout South America and Europe. He emigrated to the United States when he was in his 20s, and established a home in Los Angeles where he managed properties. He moved to Humboldt County in 2001 and helped manage the Arcata Night Shelter.

He leaves behind his son Benjamin and daughter Triana, both of Los Angeles.

Venezuela had a fun-loving and positive attitude about life, and was a loyal friend to many. He had an intense interest in spirituality and meditation, he loved learning and music, and he especially loved the ladies.

He will be sorely missed by all.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Carmelo Gamaza’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

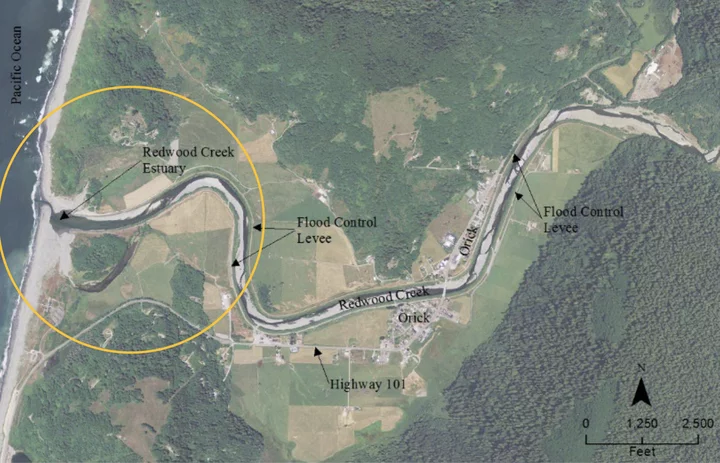

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Local Officials to Discuss Next Steps for Redwood Creek Estuary Restoration at Tomorrow’s Community Meeting

Isabella Vanderheiden / Tuesday, April 8, 2025 @ 3:39 p.m. / Environment , Infrastructure

Looking north from the Redwood Creek Estuary. | Photo: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

###

###

After more than ten years of meticulous planning and collaboration among local landowners, government officials, tribes and environmental scientists, the Redwood Creek Esturary Restoration Project is finally gaining momentum.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and Humboldt County officials will host a public meeting at the Orick Community Hall at 4 p.m. on Wednesday to discuss next steps for the estuary restoration project, which aims to revitalize critical habitat for threatened and endangered salmonid species in Redwood Creek.

“This week’s community meeting intends to introduce the Redwood Creek Estuary restoration study to members of the public that are not involved in the study through the Redwood Creek Estuary Collaborative,” Joél Flannery, senior project planner for the Army Corps of Engineers San Francisco District, wrote in an email to the Outpost. “We also hope to gain valuable insights and engage in conversation about the estuary, drainage impacts and restoration visions.”

The restoration project would undo decades of ecological degradation caused by the earthen levee system that runs through the heart of Orick. Originally designed to control flooding along the lower 3.4 miles of Redwood Creek, the levees have “reduced the size, complexity, and ecological function of the estuary,” according to the project’s description.

Over the years, Redwood Creek has become overgrown with vegetation and impaired by large sediment deposits, dramatically reducing flood capacity.

Looking at an aerial view of the estuary, as seen below, you can see where the levee system cut off a large meander on the south side of Redwood Creek. This not only altered the natural flow of the estuary but also impaired its ecological function.

Image: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

“The levee impacts to the estuary were identified many decades ago,” Flannery said. “Discussions about how to leverage [the] Corps’ authority to address the levees’ impacts to the estuary have been ongoing since at least the early 2000s.”

When the Redwood Creek Flood Control Project was constructed in the mid-1960s, the Army Corps of Engineers didn’t know the channel would rapidly accumulate sediment because the project’s designers didn’t sufficiently evaluate environmental impacts downstream. The levees were built just a few years before the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) — the nation’s first major environmental law that required federal agencies to consider the environmental impact of their actions — was enacted in 1970. As such, the project was not subject to the rigorous environmental review required by today’s standards.

The County of Humboldt periodically removes sediment and vegetation from Redwood Creek, but it’s been about a decade since any substantial maintenance occurred.

While restoration would exclude the portion of the levee system that runs through Orick, the project could alleviate flood risk upstream by enhancing floodplain connectivity at the estuary.

At the end of last year, the Army Corps of Engineers and the county, in partnership with the Redwood Creek Estuary Collaborative, initiated a feasibility study for estuary restoration. Once that process is complete in the next two and a half years, the collaborative will finalize the design selected through the NEPA process and apply for the permits needed to move forward with estuary restoration.

“Given the complexity of the study, coupled with planning and design requirements, the earliest we can expect construction would be the summer of 2029,” Flannery said. “The length of construction time is currently unknown.”

###

The Redwood Creek Estuary Restoration Project public meeting will take place at 4 p.m. on Wednesday at the Orick Community Center — 101 Swan Road in Orick. Check back later this week for coverage of the meeting.

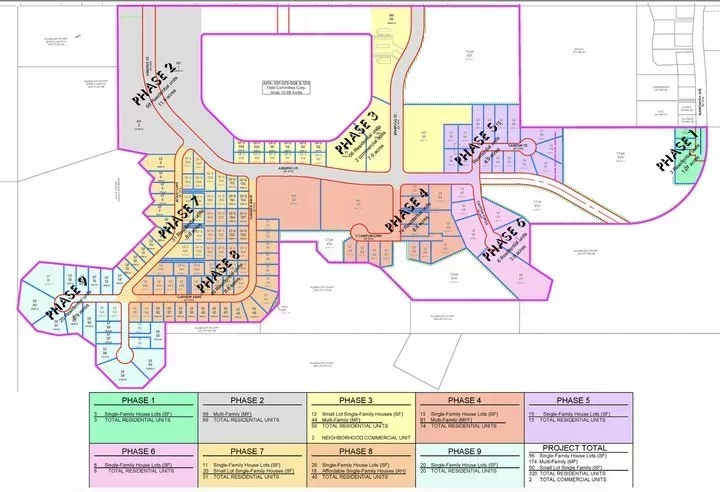

The Fate of Humboldt County’s Largest Private Housing Development in Decades Could Be Decided Tonight

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, April 8, 2025 @ 2:28 p.m. / Government

Plans for the McKay Ranch Subdivision include up to 320 residential units, including up to 172 multi-family units, along with 22,000 square feet of commercial development on a total of about 81 acres in Cutten. | File image via County of Humboldt.

###

PREVIOUSLY

- North McKay Ranch Subdivision Stymied by Inaction on Request to be Annexed Into Humboldt Community Services District

- Developer of McKay Ranch Subdivision, a Proposed 320-Unit Housing Development in Cutten, Seeks Annexation from Humboldt Community Services District

###

Humboldt County’s most significant unbuilt private housing development project could take a major step forward at tonight’s meeting of the Humboldt Community Services District’s (HCSD) Board of Directors, as that body considers a request to annex the project site into its service boundaries.

One of those directors, Heidi Benzonelli, is encouraging residents of the district to attend the meeting and have their voices heard.

“At times like this, when such an important decision is going to be made about the future of our community, that’s when I’d love to hear your personal voices,” Benzonelli said. “I can carry the message so far but there are times that we just need people to show up to meetings to tell us how you feel, and tonight is the night.”

Last time we checked in on the North McKay Ranch Subdivision, the major mixed-use development in Cutten proposed by local developer Kurt Kramer, the project appeared to have reached an impasse.

The plans, which call for up to 320 residential units and 22,000 square feet of commercial space to be built in phases over many years, hinge on getting the underlying parcels annexed into the HCSD. Without annexation, the project won’t have water, wastewater or street lighting services.

But as of a few months ago, that prospect had been stymied by a three-way disagreement over who should bear the infrastructure development costs.

The HCSD, which has already invested tens of millions of dollars of ratepayer money on infrastructure to accommodate population growth that never materialized, doesn’t want to carry the financial burden on its own.

“Given the District’s limited resources, we can only focus on pursuing grants that help reduce the cost of providing services to our existing ratepayers,” General Manager Terrence “TK” Williams said at the time.

So staff and board members tried negotiating with Humboldt County in hopes of reaching a deal to share incremental property tax revenues. But the county wasn’t particularly interested in sharing. A spokesperson told the Outpost in January that counties don’t typically divert tax revenues to community services districts unless the CSD assumes responsibility for some county-supplied services. That’s not the case here.

As shown in the map below, the North McKay Ranch Subdivision site is located just outside of the district’s service boundaries (shown in red) but within its sphere of influence (in yellow). (Zoom in to see the the project site itself, shown in black.)

In total, all phases of construction call for 50 small-lot single family units, 96 standard-lot single family units and 174 multi-family units. Another 34 accessory dwelling units (ADUs) are estimated to be developed at full build-out, according to the HCSD plan for services.

Reached by phone on Monday, Williams said the HCSD is not trying to be obstructionist on this project. Rather, staff and the board just don’t want to saddle current ratepayers with the cost of new development.

“I guarantee nobody’s gonna build over there until somebody builds a [water] tank,” he said. “If a tank is built, that opens capacity for building. It’s a matter of who’s gonna pay for the tank.”

Up in McKinleyville, the community services district is building a new 4.5-million-gallon water storage tank thanks largely to a $5 million FEMA/CalOES Hazard Mitigation Grant. But unlike MCSD, HCSD has sufficient fire-flow capacity to serve its existing ratepayers, so the district wouldn’t qualify for such hazard mitigation grants, Williams said.

With that option out, an ad hoc committee comprising board members Benzonelli and Michael Hansen has been meeting with Kramer in search of a solution.

“We ironed out some clauses to include [regarding] plans for service,” Williams said. “With that, the ad hoc committee feels pretty confident that the district is protected from continuing to pay for growth in the community.”

Those clauses, included in a staff report for tonight’s meeting, say that funding for a new 250,000-gallon water storage tank — and for upsizing the district’s water main on Walnut Drive, between Holly Street and Cypress Avenue — will be supplied by the developer (Kramer) “or other sources” but definitely not by the district. That will be a condition of approval.

A new sewer lift station will also be needed at the northeastern portion of the project site which. Kramer is planning to do that, as well. The project applicant is technically Fairhaven Cottages, LLC, a subsidiary of Kramer Properties, Inc. Kramer has already paid for an Environmental Impact Report and received project approval from the Humboldt County Planning Commission and Board of Supervisors.

If the HCSD board elects to approve annexation, the move will also require approval from the Humboldt Local Agency Formation Commission (LAFCo).

A call to Kramer for this story was not immediately returned. In previous interviews he has argued that the seemingly unending succession of impediments to this project show that the state and local governments can’t be serious about the supposed need for new housing construction.

Benzonelli said that she takes her responsibility as a representative of the public seriously, and when she’s gone campaigning door-to-door in the district’s various neighborhoods — including Cutten, Ridgewood, Myrtletown, Freshwater and more — she has heard a variety of strongly held opinions about the North McKay Ranch project. But people hardly ever attend the HCSD board meetings.

“At some point we need you to speak in the public forum,” Benzonelli said. She wanted to issue a call to all residents with an opinion on the project, not just its critics and not just its opponents — “just real, true, genuine community ideas and concerns.”

She wants residents to weigh in on the question of what they want their community to be like in a perfect world.

“And this is our opportunity to hear that: tonight, 5 o’clock. “

HCSD meetings can be attended in person at the district offices, 5055 Walnut Drive in Eureka. You can also join via Zoom by clicking here, entering Meeting ID 388 963 6754 and Passcode 202520.

And if you don’t Zoom, you can join via telephone only by calling 1-669-900-9128.

###

DOCUMENT: HCSD meeting agenda and board packet for April 8, 2025

TODAY in SUPES: An Update on Rio Dell Earthquake Recovery; The Ceremonial Recognition of Everything; No Raises For County Workers This Year?

Hank Sims / Tuesday, April 8, 2025 @ 1:20 p.m. / Local Government

How are things going in Rio Dell? A short-handed Humboldt County

Board of Supervisors got a bit of an update today, some two years and

change after a sharp 6.4 magnitude earthquake damaged some 350

buildings in the town, leaving 90 homes at least temporarily

uninhabitable.

By the end of the meeting, there seemed to be a pretty clear consensus: Homes are getting repaired, things are plugging away … but not nearly as quickly as would be ideal.

The board heard from Camille Benner, the director of family services at the Yuba/Sutter office of Habitat for Humanity. Shortly after the earthquake, the Board of Supervisors set aside $1 million for recovery efforts, and part of that went to Habitat and its partners, to help cash-strapped Rio Dellers to repair their homes. The nonprofit received $250,000 up front, with the promise of another $250,000 when its work was complete. (Read the original contract here.)

Today, Benner came to the board, which was missing both Supervisor Steve Madrone and Supervisor Natalie Arroyo, with a presentation on the the work her organization has done so far, and also with a request. All told, she said, Habitat has been part of a coalition, with different organizations and different funding sources, that has repaired 33 Rio Dell homes. It was the lead agency on seven of those cases.

A summary of one Habitat for Humanity-led repair job in Rio Dell.

The request she had

for the board was: Would it be possible to get that additional

$250,000 now, so as to start repair work on four additional homes

immediately? Those projects are pretty much ready to go, and at least

one of them is suffering from rain damage that will only get worse

the longer they delay.

“We are not in a position right now to cover the construction costs and I don’t want to leave contractors waiting to be reimbursed,” Benner said. “So these families are approved, they have all of their paperwork in and they have waited an incredibly long time and they’re very, very excited.”

The decision to release the funds will apparently be relegated to a future meeting, though the board as a whole seemed very receptive. The funds have already been budgeted, so it won’t cost any more money.

But first, as is his habit, Supervisor Rex Bohn wondered why there was so much red tape, and why the hell things are taking so damn long. He reminisced about immediate aftermath of the quake.

“I mean, we got burrito trucks galore down there in two days,” he said. “We had, I mean, there was two houses put up the same weekend. And they put them up that weekend. Two houses, foundations, everything. And you’re right, no permits or anything else. But they got the family back in the houses. Is there a way we could do this quicker?”

He had a receptive audience this time. Supervisor Michelle Bushnell, said that the whole rushed process of providing relief in the immediate aftermath of the quake was “a learning curve.” To that point, Kerry Venegas with Changing Tides Family Services, one of several local organizations working with Habitat for Humanity, told the board that she had created a system to track the work done in Rio Dell and the lessons learned throughout, and that she would be eager to share those conclusions with the county.

“We definitely have some ideas about what worked faster, because there were things that rolled out by April,” Venegas said.

The only vote the board took on the matter was to accept the report from Habitat for Humanity. It passed 3-0.

###

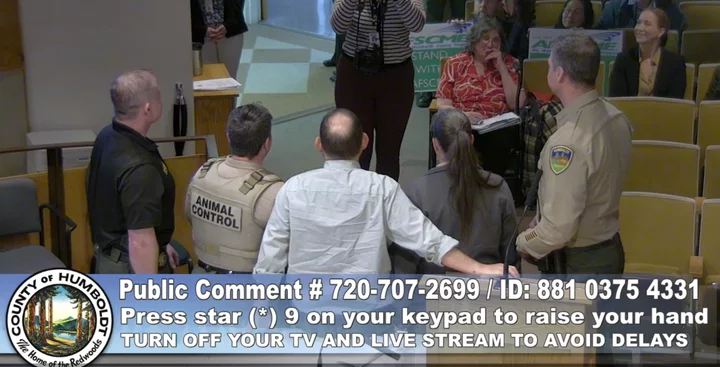

Often times, the ceremony involves the snapping of photographs with the governing member. These may be framed, if the honoree chooses to frame them. Screenshot.

Every meeting of every public agency devotes at least a little bit of time on ceremonial matters. It works like this: A member of the governing body will propose to recognize next month as “The Month of the Young Marine Biology Student,” for example. The member reads a formal proclamation, possibly written by ChatGPT, which contains lots of “whereas” clauses leading up to one climactic “therefore” clause, in which the month is so proclaimed. Then a representative young marine biology student, or possibly several of them, stands up to accept this honor bestowed upon their discipline, and talk a little bit about the importance of their work and what drew them to it.

Possibly because it was such a short meeting, otherwise, the Board of Supervisors packed in a whole enormous load of these things today, taking up a total of an hour and a half to get through what Supervisor Mike Wilson took to calling “Procl-a-thon 2025.”

Here are the things that were honored today:

- The Grange.

- The Child Abuse Services Team.

- Young children.

- Humboldt Sponsors.

- Crime victims’ rights.

- Sexual Assault Awareness Month.

- National Public Health Week.

- Police dispatchers.

- Animal control officers.

Click those links to read florid language in praise of those things.

“Sometimes I have people say, what does Humboldt County government do?” Bushnell mused near the end of the item. “And today we did everything from sheriff’s department to dispatchers to the DA to public health and a lot of proclamations to childcare … And there was a lot of happy things today and not so happy things, but it is what makes us work as a community.”

###

And that was almost all. As Izzy wrote yesterday, a potential settlement agreement concerning Kernan Construction’s controversial Glendale gravel operation, originally scheduled for today, was put off until next week.

But also: Coming out of the board’s closed session, which was largely devoted to ongoing negotiations with the unions representing county employees, Bushnell, the board’s chair, had an announcement.

“So typically the board addresses their compensation and benefits once all bargaining units have been negotiating,” Bushnell said, “That said, I would like to direct staff to return with an item next week to publicly state that the board does not intend to increase their base pay in calendar year 2025.”

Union negotiations have been tense this year, and it looks like they’re about to get more tense yet.