(UPDATING) 101 CLOSED: Broadway Street in Eureka is Closed Between 14th and Wabash Following Fatal Collision

Hank Sims / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 4:47 p.m. / Traffic

Photo: Ryan Burns.

UPDATE, 5:25 p.m.: Commander Wayne Rabang of the Eureka Police department tells the Outpost that his team is still investigating the incident. There is no indication that DUI is a factor, Rabang said.

Rabang confirmed that the decedent owned a black dog, and that they’re not certain where the dog is now. He didn’t have a better description of the dog yet.

The vehicle involved in the crash was a motor home, which is now parked in the Patriot gas station. Police have been looking it over.

###

UPDATE, 5:01 p.m.: Eureka Police Department spokesperson Laura Montagna confirms that this was a vehicle v. pedestrian collision, and that the pedestrian is deceased.

###

ORIGINAL POST:

Caltrans is noting that Highway 101 is closed between Wabash and 14th just ahead of the evening commmute. Avoid the area.

Several people have told the Outpost that there was a vehicle v. pedestrian collision at the site. The Outpost’s Ryan Burns is en route, and we will update.

Until then: If there’s a stop sign in the map below at the moment you’re reading this, the road is still closed.

BOOKED

Today: 4 felonies, 9 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

0 Sr299 (RD office): Traffic Hazard

1656 Union St (HM office): Road/Weather Conditions

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Pickup Crashes Through Fence Into Yard on West Sonoma Street in Eureka

RHBB: Afternoon Crashes Add to Day of Hail-Related Collisions Across Eureka Area

RHBB: Reckless-Driver Reports Preceded Major Broadway Crash That Seriously Injured One Woman

A (Growing) Number of Runners Are Planning to Run 62 Miles Between All Five Murphy’s Next Month

Dezmond Remington / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 3:06 p.m. / LoCO Sports!

Pete Ciotti outside the Jogg’n Shoppe. Photo by Dezmond Remington.

What’s 62 miles? Truly, how long could 62 miles be? Well, conveniently, if you split the distance up just right, distribute it around a bit, put some here, some there, it’s pretty much precisely the distance between all five of the Murphy’s grocery stores in Humboldt County.

Wait, you’re thinking. This feels kind of like an article I’ve read before, in this same esteemed publication. Has the erstwhile dependable Lost Coast Outpost made a mistake?!

No. That does not happen. That article you’re thinking of was about cyclists, and it ran last year. The particular breed of endurance freaks traveling all 62 miles between the Murphy’s this time are doing it on foot.

Runners will tackle the Murphy’s 100k on March 14. (See, that’s how you know this is a footrace: a cyclist would call it a metric century.) From the Trinidad Murphy’s, they’ll run down Scenic Drive to Clam Beach onto the Hammond Coast Trail to the Arcata Westwood Murphy’s, then out to Glendale, back to Arcata, down the Bay Trail to Cutten, and then come right back to Sunny Brae for a cool 62.

Organized by Pete Ciotti, the unflaggingly enthusiastic ultrarunner who also organized last month’s sufferfest, the race is also a fundraising effort for the businesses and residents affected by the Jan. 2 fire. There’s not a registration fee, although he does ask that runners interested in completing the run donate to them through the GoFundMe links supported by Humboldt Made on the Arcata Chamber of Commerce‘s website. Murphy’s is also planning to contribute by asking customers to round up to the nearest dollar when checking out for the week prior to the race; the sum of the differences will go through the chamber.

Ciotti told the Outpost that he was inspired by his two-wheeled predecessors, but the idea had several parents. He said Murphy’s was a good local business worth supporting; he wanted to run a 100k this year, but also wanted to avoid registering for too many races; he’s been focusing on organizing his own local events; and he’s been trying to help the fire’s victims however he can.

Ciotti said Murphy’s was “stoked” about the idea and will support the runners as well. Employees will set out aid stations for the runners at every location.

About 15 people have signed up to run since Ciotti put the word out yesterday. One group is planning to run a relay from one store to the next.

Although running 62 miles in a day is no easy feat, Ciotti said it’ll be a great opportunity to get some fresh air, help those in need, and perhaps make some new friends.

“It’s a great way to get everyone moving and see all the cool spots around the area,” Ciotti said, listing off the Bay Trail, Trinidad, Clam Beach, and a few other places the course winds through. “I encourage everybody to check out the local run clubs around town…Everybody out there promoting running and being healthy and doing good stuff. In these dark times, it’s good to have people like that who are doing positive things.”

Interested in joining? Email Pete Ciotti at PeteLovesRunning@gmail.com.

Amazon Confirms Plans for a Distribution Warehouse in McKinleyville

Ryan Burns / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 1:01 p.m. / Business

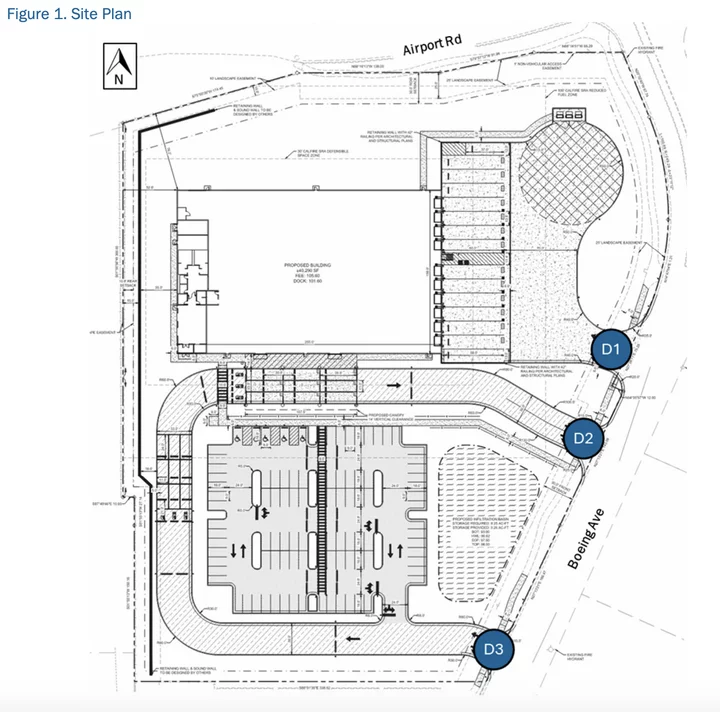

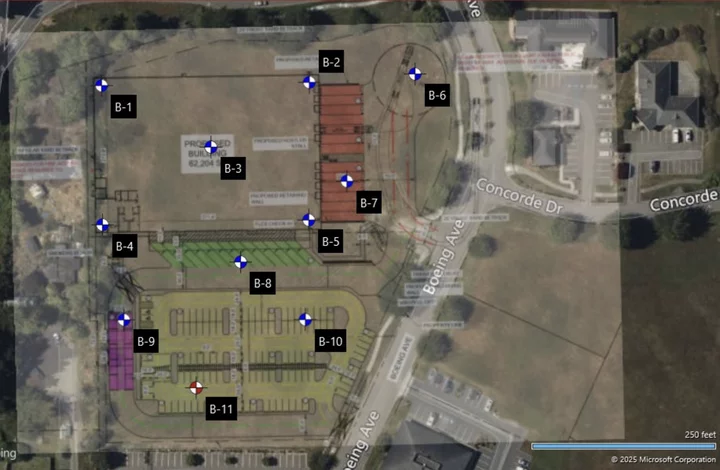

Schematic illustration shows the outline of an Amazon warehouse and two parking lots just off the freeway by the airport in McKinleyville. | Images via Humboldt County.

###

Amazon, the world’s largest online retailer, plans to build a “last-mile” distribution warehouse near the Humboldt County Airport in McKinleyville, a company spokesperson confirmed to the Outpost on Thursday.

This thing will actually be fairly small, by Amazon standards. Planning documents describe a single-story commercial warehouse of 40,290 square feet, which might sound impressive until you consider that the company’s large fulfillment centers average around 20 times that size (800,000 square feet) and some mega-sites exceed 4 million square feet. (An acre is 43,560 square feet.)

Even Amazon’s other rural-focused delivery stations are typically larger. One being built in Redmond, Ore., for example, will be 83,559 square feet. Amazon considers 150,000 square feet to be “medium-sized” while “small facilities” are 60,000 square feet or less.

Here’s the sum total of what the mega-retailer was willing to say publicly in response to a list of questions:

“Amazon [plans] to open a delivery station in Humboldt County to better serve customers in the region,” company spokesperson Natalie Banke wrote in a prepared statement. “We’re early in the process and will share more details as plans progress.”

Fortunately, more details are already available in planning documents and emails, some of which were first reported by Lisa Music of Redheaded Blackbelt. (Like her, the Outpost obtained the documents via a Public Records Act request to Humboldt County.)

The warehouse and a parking lot will be located at 3110 Boeing Avenue, adjacent to the 101 offramp to Airport Road. Plans indicate a separate lot for fleet vans and employee parking located just south of the federal courthouse.

Here’s a map of the location, with the upper perimeter (outlined in red) showing the location of the warehouse and northern parking lot while the lower perimeter shows the location of the southern parking lot:

And there’s more! Below is a site plan for the warehouse and northern lot. Loading docks are slated for the southern edge of the building. A pair of new stormwater ponds, each approximately 0.2-acres big, will be constructed east and southeast of the warehouse, and a third pond (about 0.3 acres) will be built near the southern parking lot.

Engineering plans for an Amazon delivery warehouse and northern parking lot. | Plans by Nv5 Global, Inc., obtained via County of Humboldt.

###

In all, there are six parcels incorporated into these plans, with a total project size of about 9.4 acres. Line-haul delivery trucks will access the warehouse via a driveway on Boeing Avenue, according to a project description prepared by the development company Panattoni.

“Delivery stations like this one power the ‘last mile’ of [Amazon’s] order process and help speed up deliveries,” Panattoni Senior Development Manager Sonya Kinz explains in a project description prepared for the county. “Packages are shipped to a delivery station from [Amazon’s] nearby fulfillment and sortation centers, loaded into delivery vehicles and delivered to customers.”

How many jobs will be created by this project? According to this project description, 115 employees are expected to be onsite daily during off-peak periods with up to 172 during seasonal spikes.

Site operations will occur 24 hours a day, with the bulk of employee vehicle trips taking place between 7-9:30 a.m. and 7-8:30 p.m. Line-haul truck trips will mainly occur overnight, between 9:30 p.m.-5:30 a.m., according to the project description.

But it won’t just be Amazon-employed delivery drivers going in and out. The company has a program called Amazon Flex, which works a lot like Uber and Lyft, with delivery “partners” using their own vehicles to deliver packages while maintaining control over when, where and how often they work. That’s the pitch, anyway.

“Delivery stations offer entrepreneurs the opportunity to build their own business delivering [Amazon’s] packages, as well as independent contractors the flexibility to be their own boss and create their own schedule delivering,” the project description reads.

There’s expected to be 112 “flex” drivers each day between 10:30 a.m. and 1 p.m., increasing to 172 drivers during peak seasonal periods. The distribution center will generate a total of 542 daily trips (in/out), increasing to 828 daily trips during peak seasonal periods, the plans say.

Here’s another rendering of the warehouse and northern parking lot:

Rendering from a geotechnical engineering report by Terracon.

And here’s the southern lot:

The land is already zoned as a business park, which means it won’t need to be changed. The parcels are currently owned by Stephen Moser and Dan and Debra Woods, according to the documents we’ve reviewed.

What does the property look like currently? Here’s the northern parcel:

And here’s the southern:

Of the 18 county-protected trees onsite, the project would remove three and while preserving the other 15.

So, what will the place look like once it’s built? Well, good news and bad news on that front. The good news? Panattoni did create visual renderings of the warehouse. The bad news? Those renderings have the building almost completely obscured by surrounding landscaping.

Here’s the view from the northeast corner of the property:

And here’s the view from the northwest:

Construction is expected to be completed by late 2028, according to the Panattoni description. Email communications from county planners to the development company indicate that there’s still some work to be done before construction begins. In November, county planners noted that additional field studies for bees and rare plants are required.

The California Department of Fish and Wildlife, meanwhile, recommended incorporating native landscaping species rather than the initially planned Afghan pine and Chinese hackberry. The California Coastal Commission has expressed some concerns about the mitigation approach for impacts to Environmentally Sensitive Habitat Areas (ESHA). And county staff said in an email last year that it was still awaiting comments from other agencies.

There’s bound to be plenty more to report on as the project progresses. We reached out to the county in hopes of speaking with one of the planners working on this project but have not yet heard back. Stay tuned!

‘CARE Court is a Godsend’: Why Does Humboldt’s Alternative Justice System for the Mentally Ill Succeed Where So Many Others Have Failed?

Isabella Vanderheiden / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 12:50 p.m. / Courts , Homelessness , Mental Health

Several members of the CARE Court team. From left to right: Judge Timothy Canning, Jordan Lampi, Heather Durand, Luke Brownfield and Meg Swanson. | Photo: Heather Durand.

###

Note: The Outpost has changed the names of the CARE Court participants in this story to protect their identities.

###

Eight months ago, 41-year-old John Anderson was living in a makeshift shelter in the forest, struggling to cope with untreated schizoaffective disorder. Now, he has his own apartment in Eureka and the mental health support needed to rebuild his life.

“It’s teeny-tiny, but it’s so nice to have a place of my own,” he proudly told Humboldt County Superior Court Judge Kelly Neel at a recent hearing. “And it’s all thanks to CARE Court.”

Anderson is a passionate advocate for CARE Court, a voluntary court-based treatment program for adults with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and other psychotic disorders. Enacted through the state’s Community Assistance, Recovery, and Empowerment (CARE) Act, the program is specifically designed for people who have lost their housing or become incarcerated due to untreated mental illness and either aren’t willing or lack the decision-making capacity to seek treatment on their own.

In CARE Court, county attorneys and behavioral health staff work with each participant to create a CARE agreement, a voluntary treatment plan that includes behavioral health care, medications, a housing plan and other supportive services. In rare cases, the court can order a CARE plan, an involuntary agreement that can lead to court-ordered conservatorship. Each case is initiated by a petition, which can be filed by family members, first responders, mental health clinicians or the individual seeking assistance. The court’s role is to oversee the case, monitor progress and provide accountability.

“A lot of people don’t know that they have the ability to do better until they’re forced into a situation where they actually see themselves begin to make accomplishments.”

— A CARE Court participant

When Gov. Gavin Newsom first announced the new policy in 2022, he described CARE Court as a “paradigm shift” in state’s homeless strategy that would bring people with serious mental illness off the streets and into supportive housing. However, the program has failed to live up to expectations in most California counties, with less than 4,000 total petitions submitted since the first phase of the program launched in October 2023, according to data from the state Judicial Branch.

Interestingly, Humboldt County has one of the highest referral rates per capita, with 55 petitions filed and one graduation recorded since the second phase of the program rolled out in December 2024. It’s not clear how many of those petitions were for unhoused people. There are 33 local cases still moving through the system.

“It’s just an amazing program,” Humboldt County Superior Court Judge Timothy Canning said in a recent interview. “We’ve certainly had some folks come through the program [who] didn’t do so well, but we’ve had a number of other people who have done extraordinarily well and really gotten their lives back on track. … I think a lot of its success is owed to the behavioral health department here in Humboldt. The way they’ve implemented the program [has resulted in] just amazing outcomes.”

Given his success with the program thus far, Anderson has become a sort of poster child for Humboldt’s CARE Court. After he graduates, he wants to sign on as a peer coach to help support other people going through the program.

“I’m really great at working with others [and] building them up,” he told the Outpost in a recent interview. “Now that those doors have been open to me and I know how to apply, I want to help other people who are going through similar struggles.”

Anderson started CARE Court in September 2025, just a few months after he was arrested on felony charges for threatening an elderly couple walking through the forest. He was living in the woods at the time, the result of losing both his job and his apartment. As Anderson recalls, he was deep in psychosis and “screaming at the world” when he was overheard by the couple, who took his shouting as a threat and called the police. He described his arrest as “a blessing in disguise.”

“I didn’t want to deal with life for a year. I was just trying to remove myself from everybody and everything … but there ended up being more people around than I was used to, and they thought I was yelling at them,” he explained. “The court deemed me incompetent [to stand trial because] I wasn’t in the mental state to speak straight or aware of everything that was happening. I was placed in a state psychological ward for people with disabilities … where I was properly medicated and brought out of psychosis.”

Once Anderson was medicated and stabilized, a psychiatrist went over the details of his diagnosis — schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type — when it finally clicked. He had been medicated for short, sporadic intervals before his arrest, but had stopped taking medication “because the side effects became worse than the disability.” It wasn’t until his stint at the state hospital that he actually understood his diagnosis.

“With somebody like me, the disability isn’t constant,” Anderson explained. “Half the time I’m normal — I don’t appear to have a disability at all, mentally or emotionally — but when the emotional dystrophies start to affect the psyche … the chemicals of the brain chemistry [become] unstable… and then the brain functions erratically and incorrectly. I wasn’t aware of any of these details about my diagnosis until after I got into the system, and they put me into this state mental health hospital.”

“A lot of people don’t know that they have the ability to do better until they’re forced into a situation where they actually see themselves begin to make accomplishments,” he added. “This approach is only effective if the individual has the motivation for their future and their self-stability.”

The state hospital submitted Anderson’s CARE Court petition on July 14, and his agreement was finalized two months later. In his case, the program is being used as mental health diversion under Penal Code 1001.36 to resolve his criminal charges. He’s set to graduate from CARE Court in September 2026.

‘CARE Court is a Godsend’

I was invited to observe a few CARE Court hearings last month to learn more about the dynamic between participants and the county staff who lead the program. (CARE Court participants and their family members agreed to be involved in this story on the condition of anonymity.) That’s where I met Anderson and Jason Johnson, a 40-year-old man from Southern Humboldt who’s just two months into the program.

Johnson’s parents filed a petition in October, and the court entered his CARE agreement in December. Judge Neel and the county attorneys representing Johnson didn’t get into the details of his case, but said he’s using CARE Court as an avenue to resolve criminal charges. His diversion plan is slated for approval next month.

“We’re here today to check in and encourage him to stick to his treatment plan,” Deputy County Counsel Heather Durand told the court during Johnson’s progress review hearing.

At one point in proceedings, Humboldt County Public Defender Luke Brownfield leaned over to his client and asked if he needed help with anything. Johnson quietly explained that he recently lost his job and had been pretty lonely living by himself. “I’m OK,” he shrugged.

His father, who was the only person other than me seated in the gallery, stood up and explained to the court that he and his wife were hoping to move their son to Eureka, but said they were having a hard time finding a renter or buyer for their house in Southern Humboldt. He noted that his son had been ostracized from his small community after his “break with reality” and hoped he could make a fresh start in Eureka, where he’d be closer to mental health resources.

“We can use all the help we can get,” he said.

Without missing a beat, Durand said the county could help him find housing. Looking up at Judge Neel, she asked if the court would add housing to Johnson’s priority list and provide an update at his hearing next month.

CARE Court Clinician Jordan Lampi asked if it would be possible to relocate Johnson down to Sonoma County, where his parents live, if he’s approved for diversion. Judge Neel said that could probably be arranged, but his father seemed hesitant.

“He’s just doing so well here,” he said.

Speaking to me directly, his father explained how difficult it can be for parents to advocate for their adult children when they’re experiencing a mental health crisis and navigating the judicial system. “We couldn’t even talk to his lawyer,” he said. “CARE Court is a godsend.”

He urged me to call him if the state ever threatened to dismantle the program.

The final hearing of the day was for 55-year-old Mark Thomas, whose CARE agreement was being submitted to the court for consideration. After a criminal arrest late last year, Thomas was committed to a state hospital after being deemed incompetent to stand trial. The state hospital had submitted the petition on his behalf. At the time of his hearing last month, he had not been approved for diversion and was still in custody.

Thomas’ wife and elderly mother sat in the gallery as Brownfield went over the next steps for his treatment plan. “We just want what’s best for him,” his mother said, adding that she and his wife want to stay informed of his treatment plan but don’t want to serve as his primary support. “We want a trained person [in that role] because we don’t think he’ll listen to us.”

The court agreed and also assigned Thomas a medical case manager to oversee his medications. His next hearing was scheduled for two weeks later.

‘We’re Going to Use This to Help People’

Sitting in a conference room on the second floor of the courthouse, I asked the CARE Court team — Brownfield, Durand, Lampi and Meghan Sheeran, a behavioral health clinician with the county’s Comprehensive Community Treatment (CCT) program — to try to explain why Humboldt’s program has been such a success and how it differs from other California counties.

“I gotta admit … I didn’t even want to do CARE Court,” Durand said. “I had a really negative attitude about the legislation because I didn’t think it was going to work. … I remember in, like, October 2024, telling Luke [Brownfield], ‘This is dumb, this is never going to work.’ And he looked at me, and he said, ‘We’re going to use this to help people, right?’ And I said, ‘Yeah, I’m going to try.’ We just didn’t know what to expect.”

In the weeks leading up to CARE Court’s statewide launch in December 2024, counties that hadn’t implemented the program braced for thousands of petitions to flood their systems. The local team had already been hard at work identifying people in need, many of whom had been in and out of jail or living on the streets for years.

“I think all the counties were preparing, but we already had a list of names assembled prior to implementation,” Durand said. “When December hit, we started filing petitions right away. And, from what I understand, other counties were waiting for the floodgates to open … but that didn’t happen. We had heard in the press and from the governor’s office that there were going to be thousands of cases statewide, but that just didn’t happen. … I guess we had a different mindset for whatever reason, and we just hit the ground running.”

Durand and Brownfield attributed their success, at least in part, to their ability to work well together, despite the fact that they’re generally on opposing sides of the courtroom.

“We both want people to get help,” Durand said. “And I want to point out that we’re not giving people a pass. We’re talking about people who … are just going to reoffend because they have not been set up to succeed. … We’re trying to stop that. It’s going to save the taxpayers a ton of money and it’s going to protect the public because these people actually get treatment instead of just being thrown out on the street.”

The Comprehensive Community Treatment (CCT) team, a division of county government’s Behavioral Health Services program. From left to right: Aegean Ebbay, Peter Lomely, James Rockwell (seated), Laura McArdle, Noah West-Pape and Meghan Sheeran. | Photo: Meghan Sheeran.

As a behavioral health clinician, Sheeran says CARE Court has given service providers the ability to reach a segment of the population that was previously inaccessible.

To illustrate her point, Durand drew three squares on a sheet of paper — “assisted outpatient treatment” on the left, “CARE” in the center and “LPS conservatorship” on the right. She explained that CARE Court provides another option for people who need more support than an AOT outpatient treatment program can offer, but don’t qualify for conservatorship because they aren’t considered gravely disabled, meaning they can still meet their basic needs for food, clothing and shelter.

(Note: The definition of “gravely disabled” was recently expanded to include “personal safety and medical care” as basic needs. “Gravely disabled” is also defined as “a result of a mental health disorder, impairment by chronic alcoholism, severe substance use disorder, or a co-occurring mental health disorder and severe substance use disorder.”)

“For shelter, if you got a tent and a sleeping bag and you’re camped out somewhere — that’s considered a shelter under the law,” Durand said. “What we’re talking about [in terms of grave disability] is someone who’s lying on the sidewalk without anything, and it’s 34 degrees and raining outside. … Those are the people who end up on LPS conservatorship.”

AOT Outpatient treatment, on the other hand, applies to people who are “capable enough to schedule appointments and take medication with assistance,” Durand continued. “There is help with managing medication, but they’re able to manage on an outpatient basis. In my opinion, CARE targets this in-between population: the people who aren’t sick enough to end up [in a conservatorship] but who aren’t well enough to take care of themselves.”

The problem is, CARE agreements are almost always voluntary, unless they’re tied to a court-ordered diversion agreement or a person is determined to be gravely disabled. A petition can be filed on someone’s behalf, but that doesn’t mean they have to stick with the program.

“Many of these people have had behavioral health staff try to help before, but it’s the same thing over and over again,” Sheeran said. “I can’t say ‘You must do this [program].’ I can say, ‘If you don’t, your long-term outcome is not good. Please, let us help you.’ An not every individual we’re working with is getting that picture … but we just have to keep coming back, right?”

“Every year we lose people on the streets, and anything we can do to prevent that, I would love to do,” she added. “They all deserve a whole group of people out there trying to turn things around and give them their best life.”

Durand acknowledged the public sentiment that the county isn’t doing enough to help people living on the streets. The 2024 Point-In-Time County identified 1,573 unhoused people county. Some of those folks qualify for CARE Court, but many others don’t.

“I think [there’s] a community perception of ‘Why do you have all these people out here walking around on the street and sleeping in the alcoves? They’re clearly mentally ill — why aren’t you helping them?’ They have a right to live their life the way they want to,” she said, emphasizing again that the county can’t force people into treatment unless they are gravely disabled. “I really do think [CARE] is a really valuable tool.”

It’s still a relatively new program, and the CARE Court team hopes it will become more successful as time goes on and more funding becomes available to support staff. In the meantime, they’ll continue to help who they can, like Anderson.

“Before CARE Court, I didn’t have the opportunities I have now, and they opened up all the doors to the different outlets in the community that I needed for aid,” he said. “We need to focus more on the success rates and realize how big a deal it is, even though the statistics are small.”

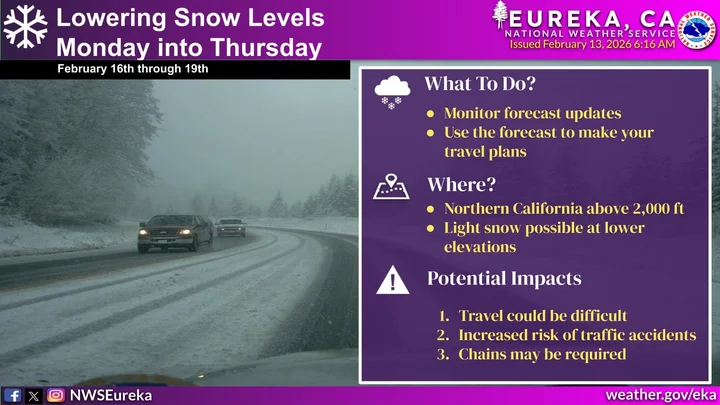

WEATHER WATCH! Rain, Rain, Rain Incoming for the Next Week, and Lots of Snow in the Hills

Hank Sims / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 12:02 p.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather

Graphic: NWS.

Well, Humboldt County’s First False Spring of the season has come to an end, looks like. It was fun while it lasted, and it’ll be fun again when Second and Third and Fourth False Springs come around.

The next six days, though? Rain likely, rain, rain, showers, rain and rain, according to the National Weather Service’s forecast for Eureka.

Up in the hils: Snow! The NWS just issued a Winter Storm Watch that warns of snow — possibly heavy snow — down to 2,000 feet between Monday and Wednesday. The big dump will likely occur Monday night, says the NWS, so be prepared for chaos on the highways Tuesday.

Though not immediately fun, we are duty-bound to remind you that precipitation is a Good Thing, particularly in winters such as this one, when we’re trailing a bit on the rainfall scale. We’re currently two inches behind the average rainfall year, and it seems like the coming flurry will get us up to par.

Factory-Built Housing Hasn’t Taken Off in California Yet, but This Year Might Be Different

Ben Christopher / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 7:51 a.m. / Sacramento

Scaffolding adorns the facade of factory-built housing Drake Avenue Apartments at 825 Drake Avenue in Marin City on Feb. 7, 2026. Photo by Jungho Kim for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

As the first home rolled off the factory floor in Kalamazoo, Michigan — “like a boxcar with picture windows,” according to a journalist on the scene — the Secretary of Housing and Urban Development proclaimed it “the coming of a real revolution in housing.”

For decades engineers, architects, futurists, industrialists, investors and politicians have been pining for a better, faster and cheaper way to build homes. Now, amid a national housing shortage, the question felt as pressing as ever: What if construction could harness the speed, efficiency, quality control and cost-savings of the assembly line? What if, rather than building homes on-site from the ground up, they were cranked out of factories, one unit after another, shipped to where they were needed and dropped into place? What if the United States could mass-produce its way out of a housing crisis?

In Kalamazoo, that vision finally seemed a reality. The HUD chief predicted that within a decade two-thirds of all housing construction across the United States “would be industrialized.”

The year was 1971, the HUD Secretary was George Romney (father of future Utah senator, Mitt), and the prediction was wildly off.

Within five years, Operation Breakthrough, the ambitious, but ultimately costly, delay-ridden and politically unpopular federal initiative that had propped up the Kalamazoo factory and eight others like it across the country, ran out of money. The dream of the factory-built house was dead — not for the first time, nor the last.

By some definitions, the first prefabricated house was built, shipped and re-assembled in the 1620s. Factory-built homes made of wood and iron were a mainstay of the colonial enterprises of the 19th Century. Housing and construction-worker shortages during the Second World War prompted a wave of (ultimately unsuccessful) attempts to mass-produce starter homes in the United States. The modern era is full of those predicting that the industrialization of the housing industry is just a few years away, only to be proven wrong.

This year, state legislators in California believe the turning-point might actually be here. With a little state assistance, they want to make 2026 the Year of the Housing Factory. At long last.

California gets ‘modular-curious’

Assemblymember Buffy Wicks, an Oakland Democrat and one of the legislature’s most influential policy makers on housing issues, is leading the charge. Since the beginning of the year, she has organized two select committee hearings under the general banner of “housing construction innovation.” The bulk of the committee’s attention has been on factory-based building — why it might be a fix worth promoting and what the state could do to actually make it work this time.

The hearings are ostensibly intended to gather information, all of which will be summarized in a white paper being written by researchers at the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley. But they’re also meant to build political momentum and legislative buy-in for a coming package of bills. Both the paper and bills are due to be released in the coming weeks.

Wicks has “select committee’d” her way to major policy change before.

In late 2024, she cobbled together a series of state-spanning meetings on “permitting reform.” Those provided the fodder for nearly two dozen bills the following year, all written with the goal of making it easier to build things in California, especially homes. The most significant of the bunch: Legislation exempting most urban apartment buildings from environmental litigation. Gov. Gavin Newsom enthusiastically signed it into law last summer.

Now comes phase two. Last year’s blitz of bills, capping off years of gradual legislative efforts to remove regulatory barriers to building dense housing across California, has, in Wicks’ view, teed up this next big swing.

“Over the last eight to 10 years or so the Legislature and the governor have really taken a bulldozer to a lot of the bureaucratic hurdles when it comes to housing,” said Wicks. “But one of the issues that we haven’t fundamentally tackled is the cost of construction.”

Factory-built housing can arrive on a construction site in varying levels of completeness. There are prefabricated panels (imagine the baked slabs of a gingerbread house) and fully three-dimensional modules (think, Legos). Interest in the use of both for apartment buildings has been steadily growing in California over the last decade. Investors have poured billions of dollars into the nascent sector, albeit with famously mixed results. In California’s major urban areas, but especially in the San Francisco Bay Area, cranes delicately assembling factory-built modules into apartment blocks has become a more familiar feature of the skyline.

Factory-built housing Drake Avenue Apartments sits under construction at 825 Drake Avenue in Marin City on Feb. 7, 2026. Photo by Jungho Kim for CalMatters

Randall Thompson, who runs the prefabrication division of Nibbi Brothers General Contractors, said he’s seen attitudes shift radically just in the last couple of years. Not long ago, pitching a developer on factory-built construction was a tough sell. But a few years ago he noted a growing number of “modular-curious” clients willing to run the numbers. Now many are coming to him committed to the idea from the get-go.

Policymakers are interested too, debating whether public policy and taxpayer money should be used to propel off-site construction from niche application to a regular, if not dominant, feature of the industry. Evidence from abroad is fueling that optimism: In Sweden, where Wicks and a gaggle of other lawmakers visited last fall, nearly half of residential construction takes place in a factory.

The renewed national interest is part of a “back to the drawingboard” energy that has pervaded policy circles at every level of government in the face of a national affordability crisis, said Chad Maisel, a Center for American Progress fellow and a former Biden administration housing policy advisor.

Yes, the country has tried and failed at this before, most notably with Operation Breakthrough. Yes, individual companies have gone bust trying to make off-site happen at scale. “But we haven’t really given it our all,” Maisel said.

Henry Ford, but for housing

If the goal is to bring down building costs, rethinking the basics of the construction process is an obvious place to start.

Over the last century, economic sectors across the United States have seen explosions in labor productivity, with industries using technological innovation, fine-tuned production processes and globe-spanning supply chains to squeeze ever more stuff out of the same number of workers. Construction has been a stagnant outlier. Since the 1970s, labor productivity has actually declined sector-wide, according to official government statistics. In 2023 the average American construction worker added about as much value on a construction site as one in 1948.

Thus the appeal of giving residential construction the Henry Ford assembly line treatment.

“When you go to buy a car, you don’t get 6,000 parts shipped to your house and then someone comes and builds it for you,” said Ryan Cassidy, vice president of real estate development at Mutual Housing California, an affordable housing developer based in Sacramento that committed last year to build its next five projects with factory-built units.

In theory, breaking down the building process into a series of discrete, repeatable tasks can mean fewer highly trained workers are needed per unit. Standardized panels and modules allow factories to buy materials in bulk at discount. The work can be done faster, because it’s centralized, tightly choreographed, closely monitored and possibly automated — but also because multiple things can happen at the same time. Framers don’t have to wait for a foundation to set before getting started on the bedrooms.

Off-site construction reliably cuts construction timelines by 10 to 30 percent, according to an analysis by the Terner Center. Some even rosier estimates have put the figure closer to 50%.

That can translate into real savings. “Factory-built housing has the potential to reduce hard (labor, material and equipment) costs by 10 to 25% — at least under the right conditions,” Terner’s director, Ben Metcalf, said at the select committee’s first hearing in early January.

But historically, it’s been very hard to get those conditions right.

The ghost of Katerra

The main hitch is an obvious one: Factories are hugely expensive to set up and run. Off-site construction companies only stand to make up those costs if they can run continuously and at full capacity. Mass production only pencils out if it massively produces.

That means factory production isn’t especially well-suited to industries that boom and bust, in which surplus production can’t be stockpiled in a warehouse and everything is made to order and where local variations in climate, topography and regulation require bespoke products of varying materials, designs, configurations and sizes.

All of which describes the current real estate sector.

“When you go to buy a car, you don’t get 6,000 parts shipped to your house and then someone comes and builds it for you.”

— Ryan Cassidy, vice president, Mutual Housing California

“In a world in which housing projects are approved one at a time under various local rules and designs and sometimes after years of piecing together financing sources, it’s hard to build out that pipeline for a factory,” said Metcalf at the early January hearing.

The particular financial needs of a factory also upend business as usual for developers and real estate funders.

Industrial construction “costs less overall but costs more in the short term. Everything is frontloaded,” said Jan Lindenthal-Cox, chief investment officer at the San Francisco Housing Accelerator Fund. All design, engineering and material decisions have to be finalized long before the factory gears start turning. Real estate investors and lenders tend to be wary of putting up quite so much money so early in the process.

The Accelerator Fund, a privately-backed non-profit, is hoping to ease some of those concerns by providing short-term, low-cost loans to developers in order to cover those higher-than-usual early costs. The hope is that traditional funders — namely, banks and investors — will eventually feel confident enough to take over that role “once this is a more proven approach,” said Lindenthal-Cox.

Such skittishness pervades every step of the off-site development process, said Apoorva Pasricha, chief operation officer at Cloud Apartments, a San Francisco-based start-up.

Scaffolding sits in front of a weather-resistant barrier on the exterior of factory-built housing, Drake Avenue Apartments, at 825 Drake Avenue in Marin City on Feb. 7, 2026. Photo by Jungho Kim for CalMatters

A subcontractor unfamiliar with modular construction might bid a project higher than they otherwise would to compensate for the uncertainty. Building code officials might be extra cautious or extra slow in approving a project for the same reason.

As the industry grows, “creating familiarity with the process helps drive that risk down,” said Pasricha. “The question is, who is going to be willing to pay the price to learn?”

Some would-be pioneers have paid it. In 2021, the Silicon Valley-based modular start up Katerra went spectacularly bankrupt after spending $2 billion in a hyperambitious gambit to disrupt the building industry. Katerra still hangs over the industry like a specter.

Brian Potter, a former Katerra engineer who now writes the widely-read Construction Physics newsletter, said he too was once wooed by the idea that “‘we’ll just move this into a factory and we will yield enormous improvements.’”

These days, he strenuously avoids terms like “impossible” and “doomed to fail” when asked about the potential of off-site construction. But he does stress that it’s a very hard nut to crack with limited upside.

“Beyond just the regulatory issues, which are real, there are just fundamental nature of the market, nature of the process, things that you have to cope with,” said Potter, whose recent book, The Origins of Efficiency, digs into how and why modern society has succeeded at making certain things much faster and cheaper — and not others.

Certain markets in California could be a good fit for factory-built construction, he added, but not for the reasons that off-site boosters typically lead with.

Construction costs in the Bay Area, specifically, are notoriously expensive. Many of the region’s most productive housing factories are located in Idaho. That arrangement might make financial sense, said Potter, not because of anything inherently cost-saving in the industrialized process, but because wages in the Boise area are just a lot lower.

That raises another potential impediment for state lawmakers hoping to goose the factory-built model: Organized labor. In a familiar political split, while California’s carpenters union has historically been open to the idea of off-site construction, the influential State Building & Construction Trades Council has been hostile.

Will the state step in?

Neither Wicks, nor any other legislator, has released legislative language yet aimed at supporting the industry. But in committee hearings, developers, labor leaders, academics and other off-site construction supporters have repeatedly pitched lawmakers on the same three themes.

Building out the pipeline is one. The state, supporters say, could keep the factories humming either by nudging affordable developers that way when they apply for state subsidies or by out-and-out requiring public entities, like state universities, to at least consider off-site when they build, say, student housing.

Insuring factories against the risk of a developer going bankrupt (and vice versa) is another common proposal. Developers and investors are hesitant to schedule a spot on a factory line if that factory’s bankruptcy will leave them in the lurch. Likewise, factories tend to charge high deposits to make up for the fact that developers go out of business or get hit with months-long delays. One solution could involve the taxpayer playing the role of insurer.

Third: Standardizing building code requirements. The state’s Housing and Community Development department already regulates factory-built housing units. But once a module is shipped to a site, local inspectors will often do their own once-over.

Some of these proposed fixes are specific to the industry. But some are regulatory changes that would make it easier to build more generally.

That might suggest that policy should ideally focus on making it easier to build stuff more generally, “not on a specific goal,” said Stephen Smith, director of the Center for Building in North America, which advocates for cost-cutting changes to building codes. For all the emphasis on building entire studio apartments inside factories, he noted that plenty of steps in the construction process have entered the modern era.

“You find walls built in factories, you see elevators, you see escalators,” said Smith. “You need to consider the small victories and think of it as a general process of (regulatory) hygiene.”

Wicks has heard all of the arguments for why emphasizing factory-based construction won’t work.

“I don’t think factory-built housing is going to solve all of our problems. I think it’s a piece of the solution,” she said. “We’re not talking about actually funding the building of factories. We’re talking about creating a streamlined environment for these types of housing units to be built.”

In other words, it can’t hurt to try again.

Trump Scraps a Cornerstone Climate Finding, as California Prepares for Court

Alejandro Lazo / Friday, Feb. 13 @ 7:41 a.m. / Sacramento

A truck driver prepares to leave after receiving a shipping container at Yusen Terminals at the Port of Los Angeles in San Pedro on Feb. 11, 2025. Photo by Joel Angel Juarez for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

The Trump administration formally rescinded the legal foundation of federal climate policy Thursday — setting up a new front in California’s long-running battle with Washington over emissions rules.

“Today, the Trump EPA has finalized the single largest act of deregulation in the history of the United States of America,” EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin said at a White House press conference. “Referred to by some as the holy grail of federal regulatory overreach, the 2009 Obama EPA endangerment finding is now eliminated.”

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the federal government may regulate greenhouse gases if they were found to endanger public health, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency issued a scientific determination that greenhouse gases indeed were a threat. By withdrawing its own so-called “endangerment finding,” the EPA is abandoning its justification for federal tailpipe standards, power plant rules and fuel economy regulations.

California opposed the withdrawal of the endangerment finding when it was proposed last year, and is expected to sue over the decision.

California Air Resources Board executive director Steven Cliff testified at the time that the move ignored settled science.

“Thousands of scientists from around the world are not wrong,” Cliff said in his testimony. “In this proposal, EPA is denying reality and telling every victim of climate-driven fires and floods not to believe what’s right before their eyes.”

Gov. Gavin Newsom said in a statement Thursday that California would take the Trump administration to court over the decision.

“Donald Trump may put corporate greed ahead of communities and families, but California will not stand by,” Newsom said. “We will continue to lead because the lives and livelihoods of our people depend on it.”

Other states and environmental groups have also indicated they could sue. They include Massachusetts, which was part of the coalition of states that sued to force the federal government to curb greenhouse gases nearly two decades ago.

Eliminating the federal basis for regulating planet-warming gases will not halt California’s climate policies, most of which – from California’s market-based approach to cutting carbon pollution to clean energy mandates for utilities — rest on state law.

In fact, the decision may open the door for California to set its own greenhouse gas standards for vehicles, a possibility that lawmakers and regulators are actively weighing.

The reversal in federal policy could also undercut arguments that federal law blocks state lawsuits against oil companies and boosts interest in expanding California’s authority over planet-warming pollution within its borders.

California prepares for a fight

Ann Carlson, a UCLA law professor and former federal transportation official, has argued that aggressive federal action against climate policy “could, ironically, provide states with authority they’ve never had before.”

Writing in the law journal Environmental Forum, Carlson theorized that California could attempt to regulate greenhouse gas emissions from cars and trucks directly under state law.

Federal law has preempted most states from setting local vehicle emission standards; California has, through a series of waivers granted under federal clean air law, obtained permission to set stricter standards than the federal government does.

This could help California’s efforts “in the long run,” Carlson wrote in an email Wednesday, “but of course withdrawing the United States from all efforts to tackle climate change is a terrible move. We should be leading the global effort, not retreating.”

In California, where cars and trucks account for more than a third of the state’s greenhouse gas emissions, California regulators at the air board and lawmakers are weighing in. When asked last year by CalMatters whether the air board would consider writing its own rules, Chair Lauren Sanchez said, “All options are currently on the table.”

“This is definitely a conversation,” Assemblymember Cottie Petrie-Norris, a Democrat from Irvine, said during a Wednesday press conference held by the California Environmental Voters. “So stay tuned.”

Ripple effects in court and Sacramento

If Washington formally exits the field of carbon regulation, states may argue they have broader room to pursue liability claims tied to wildfire costs and other climate impacts, experts said.

California has sued major oil companies as recently as 2023, in an attempt to hold them responsible for climate impacts. Oil companies have frequently cited federal oversight as a reason to dismiss climate-damage lawsuits against them.

“California is struggling with wildfire costs, for example, which are linked strongly to a warming climate,” said Ethan Elkind, a climate law expert at UC Berkeley. “I think that opens up a lot of legal avenues for states like California.”

The federal pullback has prompted lawmakers to consider expanding the Air Resources Board’s powers.

Assemblymember Robert Garcia, a Democrat from Rancho Cucamonga, this week introduced a bill aimed at affirming the state’s power to curb pollution from large facilities that generate heavy truck traffic, such as warehouses and ports, which concentrate diesel exhaust in nearby communities.

“It’s no secret that the federal government and California are not seeing eye to eye — we’re not on the same page,” Garcia said at Wednesday’s news conference. “This is an opportunity for our state, for California to step in.”