California’s Controversial New Fuel Rules Rejected by State Legal Office

Alejandro Lazo / Friday, Feb. 21, 2025 @ 10:43 a.m. / Sacramento

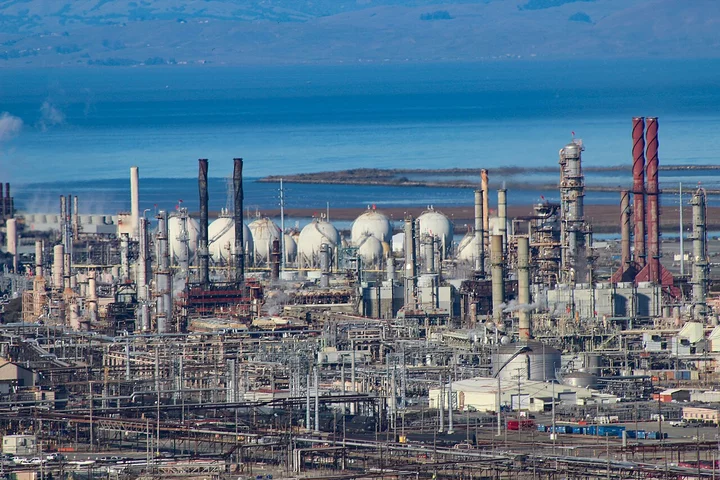

By Bastique - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0,

In a surprising twist, California’s controversial new fuel standard — a key part of its effort to replace fossil fuels — has been rejected by the state agency that reviews the legality of state regulations.

The fuel standard enacted by the Air Resources Board last year was the subject of a rancorous debate, largely because it will potentially increase the price of gasoline and diesel fuels by an unknown amount.

The rules were rejected by the state Office of Administrative Law, a state agency whose mandate is to ensure “regulations are clear, necessary, legally valid, and available to the public.” The law office informed the air board that the rule does not conform with a provision in state code that requires “clarity” in rulemaking “so that the meaning of regulations will be easily understood by those persons directly affected by them.”

The air board said it would review the order and then resubmit the rules, which would be required within 120 days. Any substantial changes, however, would require a delay, including a public comment period.

The low carbon fuels program, which offers financial incentives to companies to produce cleaner transportation fuels, aims to help transition the state away from fossil fuels that contribute to smog and other air pollution and greenhouse gases that warm the planet.

The program, which has existed since 2011, is a $2-billion credit trading system that requires fuels sold in California to become progressively cleaner, while giving companies financial incentives to produce less-polluting fuels, such as biofuels made from soybeans or cow manure.

In an initial assessment released in 2023, the air board projected that the new rules could potentially raise the price of diesel by 59 cents per gallon and gasoline by 47 cents. But air board officials later disavowed that estimate, saying that the analysis “should not be misconstrued as a prediction of the future credit price nor as a direct impact on prices at the pump.”

A report by the University of Pennsylvania’s Kleinman Center for Energy Policy predicted that the fuel standard changes could increase the cost of gas by 85 cents a gallon through 2030.

Republican legislators, who protested the rule and introduced a bill to repeal it, applauded the law office’s decision to reject them.

“Families in this state are already grappling with soaring living costs, and a gas price hike of 65 cents or more will only deepen their financial strain,” Sen. Rosilicie Ochoa Bogh, a Republican from Redlands, said in a statement. “It’s deeply frustrating that the governor’s administration ignored calls for reconsideration from the start.”

Supporters say the new rules are necessary to keep California on track for its ambitious climate goals, including net-zero emissions by 2045. But critics have warned that the new standards could push gas prices even higher in a state where drivers already pay some of the highest fuel costs in the nation.

The air board last month was forced to abandon other climate and air pollution rules that would have cleaned up truck and train emissions because the Trump administration would reject granting them waivers.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

BOOKED

Today: 8 felonies, 17 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 6

CHP REPORTS

Us101 N / Newton B Drury Scenic Pkwy Ofr (HM office): Traffic Hazard

4593 Mm299 E Tri 45.90 (RD office): Report of Fire

ELSEWHERE

100% Humboldt, with Scott Hammond: #107. Jan Friedrichsen: Veteran Rescuer Explains How Search Dogs Track, Find, And Bring People Home

RHBB: Crash Blocks Lane on Northbound U.S. 101 at Humboldt Hill Onramp

RHBB: Crash off 101 into Trees North of Willits

Study Finds: When Moths Freeze: How LED Streetlights Are Silencing the Night

OBITUARY: Imogene ‘Genie’ Cancellier, 1929-2025

LoCO Staff / Friday, Feb. 21, 2025 @ 7:34 a.m. / Obits

Imogene “Genie” Cancellier passed away peacefully to be with her Lord on January 14 at St. Joseph’s Hospital at the age of 95.

She was born in Erwin, Tennessee, August 17,1929, the youngest of four to Rex and June McKinney. She graduated from Unicoi County High School in 1946 where she enjoyed playing on the Blue Devils girls basketball team while being every bit of 5‘2” tall. She and Russell C. Cumbie married August 29, 1946, her fresh out of High School and he just back from serving in the Navy on a destroyer in the Pacific during WWII. Russell and Genie moved to Klamath in 1950, welcoming their only child Michael in 1953 and where they resided until the 1955 floods in the town of Klamath and the Klamath Glen. It was at this time she started a long career of civic engagement by volunteering in the Red Cross during the flood, later moving to Eureka with Russell and their son Michael, where she lived the rest of her life.

Working at the old Lincoln’s art, books and gift store in downtown Eureka she developed friendships with many local artists and supported the arts in Eureka. She continued working in the community as a Den Mother for Cub Scouts, the PTA, Eureka Women’s Club, and Eastern Star. She loved her Scottish heritage and proudly sported her Clan MacKenzie tartan. Frequently working as a volunteer for Hobart Brown’s Kinetic Sculpture Races, she enjoyed the spectacle of it all.

Her great love though was for Coast Guard Humboldt Bay and the Navy League where she started as a local member, working through to being a state and then national director. Known as “The Coast Guard Mom” she worked to provide support and encouragement to service members and their families. She found great joy in organizing events for families through the holidays and never took no for an answer when she asked for donations for those celebrations. She made no distinction between Admiral or Seaman and was there for them. She was justifiably proud of being able to have Eureka designated one of the first two Coast Guard Cities in the United States. She was also a strong voice in support for the Humboldt Bay Maritime Museum and Leroy Zerlang and the historic vessel “Madaket.”

In her personal life she enjoyed decorating her home for the holidays, hosting parties and dressing to the nines. When she threw a party she threw a party. She was small in stature, but larger than life. She was direct and never left any doubt where she was coming from. Caring, she could be counted on to come through for both those she loved and those she just met. She will be missed by all who knew her. To her friends and caregivers who worked compassionately so Genie could stay in her home which was her desire and wish, Blessings to you all. It was Genie’s desire that no memorial services be observed and she was interred at Sunset Memorial Park between her husbands, who preceded her in death, Captain Norman J. Hubbenette and Michael “Ren” Cancellier. Genie’s family asks that she be remembered for the joy she brought to others in life, not the sadness of her passing.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Genie Cancillier’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Melanie Jean Lorenzetti Stearns, 1970-2025

LoCO Staff / Friday, Feb. 21, 2025 @ 7:25 a.m. / Obits

Melanie Jean Lorenzetti Stearns, born on April 12, 1970, was a beloved daughter, sister, wife, mother, grandmother, and friend. As the youngest of four siblings, she grew up in the close-knit community of Fortuna, where her childhood was filled with love, laughter, and adventure. From a young age, Melanie’s warm heart and her spirited vibrant personality shone brightly, qualities that remained at the core of who she was throughout her life. For Melanie, family was the essence of her being, the heart and soul fueling her every action.

Melanie attended Fortuna Elementary School and Fortuna High School, where she cultivated a passion for learning. She went on to earn dual degrees from Humboldt State University, demonstrating her commitment and determination to succeed in all aspects of her life.

During her high school years, Melanie met her high school sweetheart, Brad Stearns. Together, over the next 38 years, they built a beautiful life filled with love, joy, and cherished memories. Their bond, forged through the trials and triumphs of life, became a beacon of enduring love, inspiring all who witnessed it. Their union was blessed with three wonderful children: Ryan, Sara, and Kayla, who were the light of Melanie’s life. Her unwavering love, protection, support, and kindness formed her family’s foundation.

Melanie embraced the role of “Mimi” to her twin granddaughters, Sienna, and Deslynn DeGraff. Watching them grow, play sports, and attend to their many other activities, brought her immeasurable joy and pride, and they became a source of endless love in her life. Melanie’s dedication to her family was unparalleled and a testament to her boundless love and compassion.

Beyond her family, Melanie’s dedication to others extended far and wide. For nearly two decades, she worked in the medical field, offering compassionate care to countless individuals in her community. Her warm gentle smile could light up even the darkest of days, offering hope and encouragement to those around her.

Melanie’s legacy is a woman of remarkable strength, always ready to lend a hand, offer support and encouragement, or share a laugh. Melanie’s laughter was infectious, her stories captivating, and her presence both comforting and inspiring. The warmth of her spirit resonated with everyone she met, touching the lives of numerous friends and loved ones. Her influence lies in the kindness and warmth she selflessly shared with those around her. Melanie made everyone feel appreciated and cherished, leaving an indelible mark on all who were fortunate enough to know her. Her love was a gift that transcended her immediate family, creating a ripple effect that impacted many lives.

Melanie’s life was a beautiful testament to the power of love, kindness, and resilience. She faced challenges with unwavering strength and grace, often putting the needs of others before her own. Her ability to find joy in the simple pleasures of life and her persistent optimism endeared her to everyone she met.

Melanie’s influence is one of love and compassion, and her memory will be forever a guiding light for those who were fortunate to have known her, inspiring those who knew her to live with the same dedication and generosity that defined her life.

Melanie was preceded in death by her beloved mother Jean Lorenzetti; her sister, Valerie Pasdera; father-in-law, Norman Stearns; cousin, David Harper; uncle, Delmar Lorenzetti; and uncle, Tom Harper. She is survived by her husband, Brad Stearns; son, Ryan Stearns; daughters, Kayla Stearns, her fiancé Ely Schoenfield, and Sara Stearn; grandchildren Deslynn DeGraff, Sienna DeGraff, Roger Lorenzetti; Mother-in-Law Rita Stearns, Greg Lorenzetti (wife Christine), Brad (wife Heidi) Nephew Josh, Niece Jessica, Brother-in-Law Rick Pasdera, Niece Nicole Pasdera; Cousin Bruce Harper (daughters Brenna and Brooke); Aunt Linda, Aunt Diane, and Dr. John. Moriarty; cousins Kevin Moriarty and Joanne Moriarty; Aunt Sharon Lorenzetti, ousins Angela Sanborn, Tara Johnson, Michelle Wigginton, Lori Bravo; Aunt Carolyn, Cousins Jennifer and Rochelle, and many more extended relatives and friends who she was devoted, dedicated, and loved so dearly.

To honor Melanie, a celebration of life will be held March 1 from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m. at the Eureka Elks Lodge.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Melanie Stearns’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Arcata Emergency Services Handled a Lot More Incidents in 2024 Than in 2023

Dezmond Remington / Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 @ 2:56 p.m. / Crime , Fire

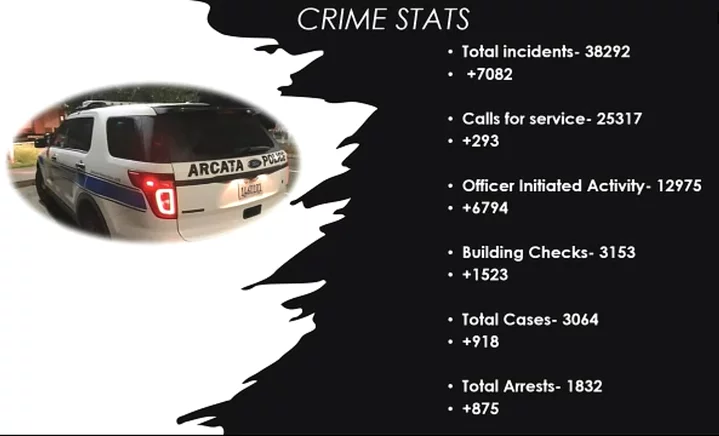

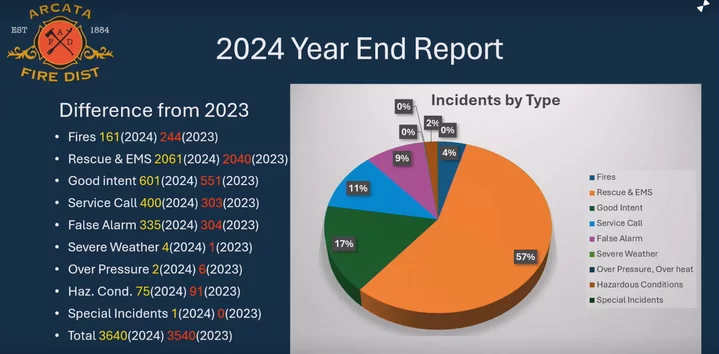

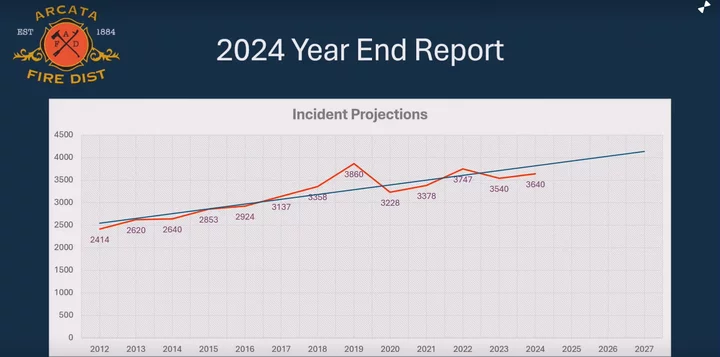

Staff presentations delivered last night at Arcata’s City Council meeting from police investigations commander Todd Dokweiler and fire chief Chris Emmons show Arcata’s emergency services are fielding more calls for service than ever.

Dokweiler and Emmons gave 2024 year-end reports that included total statistics for calls over the entire year, as well as things like APD’s arrests and Arcata Fire Department’s fires.

APD’s statistics were up across the board. There were about 38,000 total incidents in 2024, an increase of over 7,000 from 2023. Much of that came from an increase of around 6,700 officer-initiated incidents, a category that includes things like traffic stops and wellness checks. APD received over 25,000 calls for service in 2024, a few hundred more than in 2023.

Don’t stress too much about the data — there’s not a massive crime wave currently sweeping through Arcata. Dokweiler attributed the large uptick to hiring nine additional officers in 2024.

Overall, APD made 1,832 arrests in 2024, up from 957 in 2023.

There were 3,650 incidents for AFD in 2024, up 100 from 2023. There were 83 fewer fires in 2024. There were approximately 2000 calls for medical services, which is about the same as in 2023.

AFD is handling far more calls now than even in the recent past. In 2014, AFD was called only 2,640 times, and even that was a large bump from years past.

“When I started in 1992, we were running somewhere in the neighborhood of 800-1000 calls, and now we’re running 3,600,” Emmons said. “We’ve increased tremendously.”

Members of Service Workers Union Protest Republican Budget Resolution That Would Slash Medicaid Funding

Ryan Burns / Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 @ 2:45 p.m. / Activism , Government

Members of SEIU Local 2015 protest outside of Rep. Jared Huffman’s district office in Eureka. | Photo by Ryan Burns.

###

Local home health care workers gathered outside of Rep. Jared Huffman’s Eureka district office this afternoon to demonstrate against a Congressional Republican budget proposal that would slash billions of dollars in spending on Medicaid, threatening health care coverage for some of the 80 million U.S. adults and children enrolled in the safety net program, according to the Associated Press and other news outlets.

Clad in their custom-issue purple t-shirts, the assembled union members are employed through California’s In-Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program, which provides assistance to seniors and disabled individuals while allowing recipients to remain in their homes.

Jonathan Peña, an organizer with SEIU Local 2015, said the GOP budget proposal, which aims to reduce federal spending by $880 billion over the next decade, would create an existential threat to the IHSS program. Roughly $15.3 billion of the program’s $25 billion annual budget currently comes via federal funding.

“So if this passes, it’s either going to get rid of the IHSS program or it’s going to defund it by a large amount, which means people are not going to have care,” Peña said. “People are going to be homeless, and the economy is going to get even worse.”

Neither Huffman nor any members of his staff were present at the demonstration, and while the North Coast’s Congressional representative has voiced support for in-home caregivers, the demonstrators said they hoped to reinforce that stance and encourage him to convince his Republican colleagues to oppose the spending bill.

[CORRECTION/UPDATE: Local District Representative John Driscoll met with the demonstrators shortly after the Outpost interviewed them.]

Some of the workers described what the loss of the program would mean to them personally.

“I have a daughter who’s 13 and has severe autism, and I am her mom and her caregiver,” said a care worker named Danielle. She said it’s already difficult to find backup help. “Nobody wants to do this work. I can’t get respite care; I can’t get any help. So if this [spending proposal] goes through, I’ll have to get another job and find somebody to take care of my daughter, which is already impossible.”

With a vote on the spending bill scheduled for early next week, Peña said he and his fellow demonstrators hoped to drop off letters for Huffman in which IHSS caregivers tell their stories and describe how they’d be affected if IHSS ceases to exist.

“The elderly are going to be left to die in their homes,” said Heidi Chandler, another union member at today’s gathering. “The person I take care of doesn’t have transportation. I do his shopping and his medicines, everything. I’m the only contact he has.”

Danielle wondered how the budget might impact The Glen Paul School, which serves severely disabled students at its Eureka main campus and in classrooms across the county.

“The Area 1 on Aging also is going to be affected by this, and they provide meals on wheels,” Chandler said. “I mean, it’s going to devastate Humboldt County if this happens.”

SEIU Local 2015 members plan to demonstrate again outside the Humboldt County Courthouse on Monday.

Eureka City Council Tables Discussion on Increased Fees for Sewer Lateral Repairs Due to Pushback From Local Realtors, Homeowners

Isabella Vanderheiden / Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 @ 11:50 a.m. / Infrastructure , Local Government

Screenshot of Tuesday’s Eureka Council meeting.

###

After hearing from more than a dozen local realtors and homeowners at Tuesday’s meeting, the Eureka City Council unanimously voted to table its decision on a proposed update to the 2024-25 fee schedule that would increase the cost of sewer lateral replacement for property owners with especially deep or problematic plumbing. The city council will revisit the item at its next meeting.

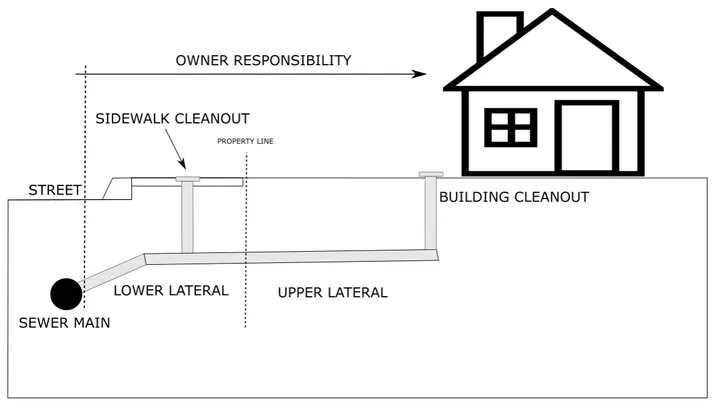

The proposed fee schedule would, if approved, create three “fee in lieu” categories for repairing lower laterals — the section of sewer pipe that runs from the property line of a building to the public sewer main under the street — as required by the city’s Private Sewer Lateral Ordinance. Under the ordinance, homeowners are responsible for blockages occurring anywhere in the lateral. If an inspection determines the lower lateral determined to be defective — or if it’s made of clay — it must be replaced.

Graphic: City of Eureka

The “fee in lieu” system was introduced after the ordinance was adopted in 2019 to address ongoing issues with follow-through. Instead of hiring their own contractor, property owners can pay a set fee to the city — currently set at $8,000, payable upon the sale of a building — that allows staff to take care of repairs on their behalf.

However, over the years, staff have encountered lower lateral installations that exceed the average cost due to the depth and/or complexity of the sewer lines. The updated fee schedule would impose additional fees for lower laterals that are more than five feet underground. The proposal, if passed, would increase the “fee in lieu” for deep lower laterals to $12,600. Fees for “non-standard installation” would be determined by the city engineer.

Speaking at Tuesday’s meeting, Eureka City Manager Miles Slattery emphasized that people who have already gone through the city’s loan process or are “in the queue” would not be affected by the fee increase. “What this does is it prevents the overall cost [from] going up because these lower laterals are costing people more money.”

“The rate was established at $8,000 for those lower laterals … but what we’re seeing now are there certain properties that skew that average.” Slattery explained. “The reason for the deeper lateral costs is because the contractor having to comply with OSHA. Once you get to five feet [below the surface], you have to provide shoring, [which] increases the cost to do those lower laterals. Staff thought it was more equitable … to separate that out.”

Councilmember Renee Contreras-DeLoach seemed to support staff’s approach, noting that she would be “completely uncomfortable” with spreading the cost to other property owners or imposing additional fees on ratepayers. “That would be unjust, I think,” she said.

During the public comment portion of last night’s meeting, several local realtors raised concerns about the increased costs, especially the new category for “non-standard installation.” Jill MacDonald, a realtor with Coldwell Banker Cutten Realty, said she would be willing to accept the fee increase for deeper laterals but felt the unspecified fee for “non-standard installation” was a step too far. She gave an example of a “non-standard” situation where a house sold for $247,000 and the estimated cost for lateral replacement was a jaw-dropping $30,000.

“That’s why we’re outraged,” she said. “There has to be a cap, it can’t just be an open-ended number. And we can’t have our sellers go into escrow and not know what they’re committing to.”

About a dozen other real estate agents, mortgage brokers and property owners echoed MacDonald’s concerns, several of whom accused the city of using the fee structure as a way to generate additional income.

“Due to many decades of not keeping their side of the street maintained, the City of Eureka is looking to generate income for repairs to its sewer mains and lower laterals by taking of homeowners’ equity, and now they want even more money during a real estate transaction,” said Victoria Copeland, a realtor with the Key Real Estate Group. “There are many other ways that money for this maintenance could be generated. The city did not have to institute this ordinance — they chose this route.”

Following public comment, Slattery said the lateral installation that was projected to cost $30,000 was put on hold “because it was so cost prohibitive,” noting that it is a unique situation that is typically exclusive to commercial properties or housing developments with “interties” — trunk-style sewage lines that service several units.

“We’re not here to gouge people but at the same time, we’re not here to get sued by EcoRights again,” Slattery added. “So we need to demonstrate that we’re trying to get to a point there will be something coming back to council to address these issues of interties that happen in the city. … The frequency isn’t as high as what you’re hearing [tonight], but it does definitely happen.”

Councilmember Scott Bauer and Councilmember Leslie Castellano floated the idea of imposing a cap on fees for “non-standard installations” but City Attorney Autumn Luna urged the council to stick to the proposed update to the fee schedule.

After a bit of discussion Luna and the council agreed to revisit the issue with City Engineer Jesse Willor present. Councilmember G. Mario Fernandez made a motion to postpone the discussion

Before closing out the discussion, Castellano reiterated Contreras-DeLoach’s previous point that the fees should not be passed onto ratepayers. She also said “it’s not fair” that property owners are tasked with fixing inherited sewer issues.

“There’s a million things that we’ve inherited now in 2025 that aren’t fair,” Castellano said. “I would love to go back and have a stern talking to folks in, like, 1950, but I can’t do that. … We have to address a lot of inequity right now … and I commend staff for doing their best to try to make it as fair as possible, given the current situation. … We don’t want to increase those rates and cause that harm to people who are residents in our communities.”

The voted 5-0 to continue the discussion at its next meeting on Tuesday, March 4.

###

What else happened at Tuesday’s meeting, you ask?

- Eureka Police Chief Brian Stephens presented the department’s annual report for 2024. EPD has made “significant strides in recruitment, filling vacancies, and increasing staffing to levels we haven’t seen in years,” Stephens said. “While our patrol division and dispatch remain short by three officers and three dispatchers, respectively, the rest of the department is fully staffed,” he said, adding that EPD has seen a surge in applications for all positions.

- During the non-agenda public comment portion of the meeting, about a dozen people called on the city officials to do more to address Eureka’s homelessness crisis. Some speakers criticized the city for failing to provide adequate shelter during extreme weather events, while others took aim at the city council’s recent decision to consolidate the city’s Camping Ordinance and the Sitting or Lying on Sidewalks Ordinance into a single, simplified ordinance with “more teeth.” Elsewhere in the meeting, councilmembers DeLoach and Fernandez volunteered to meet with staff monthly to discuss emergency shelter opportunities and guidelines.

- The city council also received a report on tsunami and disaster preparedness from Ryan Derby, the county’s director of emergency services. The presentation focused on the tsunami warning that was generated by the Dec. 5 7.0 magnitude earthquake and the chaotic response that followed. Derby recommended that local municipalities and participate in a countywide tsunami evacuation drill and bolster access to information about disaster preparedness.

###

California Lawmakers Scramble to Fix ‘Lemon’ Vehicle Law — Again

Ryan Sabalow / Thursday, Feb. 20, 2025 @ 8:24 a.m. / Sacramento

A mechanic works on a vehicle in Fresno in 2022. California’s lawmakers are scrambling to update California’s lemon law that gives car owners the right to demand car companies fix or replace defective vehicles under warranty. Photo by Larry Valenzuela, CalMatters.

For more than half a century, California’s “lemon” law was considered one of the best in the nation at giving consumers the legal right to demand car companies fix or replace defective vehicles still under warranty.

Now, California lawmakers are scrambling to repair recent changes they made to the law to satisfy the very car companies accused of making so many lemon vehicles that their lawsuits have been clogging the state’s courts.

But the “fixes” lawmakers are considering have angered consumer groups, frustrated legislators and seemingly divided the car makers between ones that face a lot of lemon lawsuits and the ones that don’t.

“I think what we have is a messy and frankly — all due respect — illogical resulting situation,” Sen. Roger Niello, a Republican whose family owns several car dealerships in the Sacramento area, said at a hearing last week. “I feel like I’m in Alice in Wonderland, quite frankly. What’s up is down and what’s down is up.”

With hope of granting relief to the courts, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation last year intended to speed up the process, in part, by cutting years off the time consumers can exercise their rights to get their defective vehicles fixed or replaced. The law also puts more responsibilities on car owners to initiate claims instead of on the car companies.

But that law divided car makers because those that face fewer lawsuits wanted more time to prepare their best defense, and they felt it was too friendly to lemon law attorneys. So when he signed the bill, Newsom told lawmakers to act quickly this year to allow car makers to opt out of the new process and continue to work under the old rules.

Now, legislators are racing to pass the changes before the new law takes effect April 1. And they need a two-thirds vote of the Legislature to make the bill effective immediately.

Meanwhile, they’re hearing concerns about a confusing two-tier lemon law with fewer consumer protections that is primarily intended to help the companies facing the most lawsuits. Just four companies are responsible for more than 70% of California’s lemon law cases: GM, Stellantis (formerly Fiat Chrysler), Nissan and Ford, according to consumer groups.

It makes Susan Giesberg furious.

She spent almost a decade working on lemon law issues at the California Department of Justice. Now retired, she says she and her husband had to invoke their rights under the state’s lemon law under the old rules when their Chevy Volt broke down last summer.

“This lemon law has gone through Republican and Democratic (attorneys general) and governors with support over the years,” she said in an interview. “It’s just so shocking that under Democratic leadership that this would have gotten through.”

So how did it?To answer that you have to go back to August, in the final chaotic days of the legislative session.

How lawmakers jammed through new lemon law

As lawmakers were rushing through hundreds of pending bills – most of which had been under discussion for months – two Democrats, Sen. Tom Umberg of Santa Ana and Assemblymember Ash Kalra of San Jose, changed a stalled child-support bill into new, never-vetted legislation that sought to reform how lemon law disputes are resolved. Stripping out stalled legislation, replacing it with a completely different bill and jamming it through at the last minute is disparagingly known in the Capitol as a “gut-and-amend.”

The lawmakers acknowledged that the bill, Assembly 1755, was the product of months of secret negotiations between U.S. car companies – primarily General Motors – consumer attorneys and judges who were frustrated that their courtrooms have become clogged with lemon law cases.

Between 2018 and 2021, GM’s 9,800 lemon law suits accounted for nearly one in three lemon law suits filed in California, according to the most recent stats from consumer groups. A company spokesperson in a written statement to CalMatters defended its record and the new California law.

“General Motors is continuously recognized by top consumer intelligence groups for vehicle reliability, quality, and customer loyalty,” GM spokesperson Colleen Oberc said in an email. She called the legislation “a pro-consumer bill that will help drivers get back on the road sooner, while also helping clear court backlogs, benefitting both customers and the auto industry.”

California defines a “lemon” vehicle as one that has serious warranty defects that the manufacturer can’t fix, even after multiple attempts. The lemon law applies only to disputes involving the manufacturer’s new vehicle warranty.

If the manufacturer or dealer is unable to repair a serious warranty defect in a vehicle after what the law says is a “reasonable” number of attempts, the manufacturer must either replace it or refund its purchase price, whichever the customer prefers, according to the California Department of Consumer Affairs.

Disputes can be resolved through arbitration or in court if a buyer sues.

The number of lemon law cases in California courts climbed dramatically since 2021. There were nearly 15,000 filings in 2022 and more than 22,000 in 2023. In Los Angeles County, nearly 10% of all civil filings are now lemon law cases.

Kalra and Umberg pitched their legislation last year as a way for auto companies and car buyers to settle their disputes quicker and without needing as much time in court.

But Tesla and several foreign auto companies including Volkswagen and Toyota that aren’t sued nearly as much said they were cut out of negotiations. They opposed the legislation.

Consumer groups, meanwhile, called the legislation a blatant and shameless attempt at weakening the lemon law by the very companies that get sued the most because they sell the most defective vehicles.

There was a lot more in the bill, which was about 4,200 words long (the equivalent of a 16-page double-spaced term paper). What’s more, the bill’s legislative analysis, intended to explain the context and impact of a bill in non-legal language for lawmakers, was more than 10,000 words.

The bill passed easily even though some lawmakers complained they were uncomfortable with having to decide such a complicated, confusing piece of legislation so quickly.

“There wasn’t a single person who represents the people of California who knew about this and was a part of those conversations – for months,” Democratic San Ramon Assemblymember Rebecca Bauer-Kahan told her colleagues on the Assembly Judiciary Committee in the final days of the 2024 legislative session. “They dropped this in our lap, and they expect us to buy an argument related to the urgency that feels, to be honest, not real. And we’re supposed to move this in a week’s time.”

Newsom signed the bill in September, with an accompanying letter to lawmakers demanding they fix the law.

Meanwhile, just a few weeks after Newsom signed the bill, the California Supreme Court weakened California’s lemon law even more. The court ruled that the state’s lemon law doesn’t require manufacturers to honor a car’s warranty when it’s re-sold as a used vehicle.

Before the Supreme Court’s ruling, courts had interpreted the lemon law to require manufacturers to replace or repair a defective used car or truck if the clunker was sold within the window of its original new-vehicle warranty.

Uncomfortable lawmakers pass bill anyway

Fast forward to last week and the Senate Judiciary Committee’s first hearing of the new two-year session. There was one bill on the agenda: Senate Bill 26, the legislation that Newsom requested. The new bill does not address the state Supreme Court ruling.

And again the clock is ticking toward a new deadline.

The bill frustrated Sen. Aisha Wahab, a Democratic senator from Fremont. She told her colleagues she was worried the two-track legal system for different car companies would make an already confusing scenario for desperate car owners more difficult to understand.

“I’m very concerned about those first-time buyers, those immigrant communities, those people that don’t have the privilege to understand half of the stuff that was mentioned here,” she said. “It makes it too hard to begin with.”

Umberg, the bill’s author, suggested that after lawmakers pass this bill to meet the April deadline, they might need to pass other legislation to address lawmakers’ concerns as well as the Supreme Court’s used-vehicle ruling.

That didn’t sit well either.

“It’s unfortunate that protections for the consumers have gotten so complicated that we can’t more easily explain this law or the previous law, and I thought this was a clean-up (bill),” said Sen. María Elena Durazo, a Democrat from Los Angeles. “Now it seems like there may be a clean-up to the clean-up, maybe another clean-up, you know, after that.”

Nonetheless, the bill ended up easily passing the 13-member committee. Wahab declined to vote, and Democratic Sen. Angelique Ashby of Sacramento cast the only “no” vote. Ashby was one of the lawmakers who opposed last summer’s bill as well.

“I still believe that it does not do enough to remove unsafe vehicles from our communities,” she said of this latest bill. “In fact, I argue that this might have more unsafe vehicles in our communities, and I think I would not be alone in that assessment. I don’t think it holds manufacturers accountable.”

Sen. Niello said he had to reluctantly vote for Umberg’s bill since it would help negate – at least for some auto companies – the legislation he also opposed last summer.He said he wished lawmakers would just scrap the bill Newsom signed last year “and bring all of the interested parties together” to re-negotiate reforms to the lemon law, which he said probably could use some after five decades.

Instead, he had to hold his nose and vote for another rushed bill.

“This is a perfect example of why we should not be approving legislation that is a gut and amend at the last minute of the end of session,” Niello said.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.