This Recent Stretch of Nice Weather Has Been a Lie

Hank Sims / Monday, March 10, 2025 @ 2:20 p.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather

(Source)

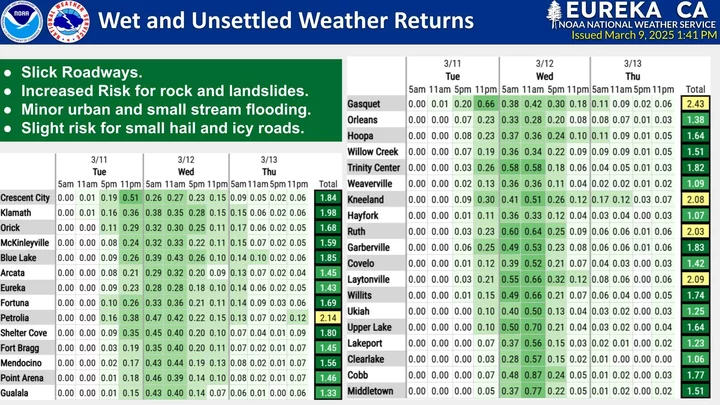

Our friends and yours at the National Weather Service’s Woodley Island HQ, which still exists, are sending out the warning! Rain is coming! Don’t believe in this nice sunny stretch! Winter weather is not done with you yet!

Kinda crazy, since a peek at our homepage and the LoCO Weather Report — which is actually National Weather Service’s work, as is all weather-related services on the Outpost and indeed everywhere else you get weather information — shows that we’re nearly 10 inches of precipitation ahead of the average or “normal” water year.

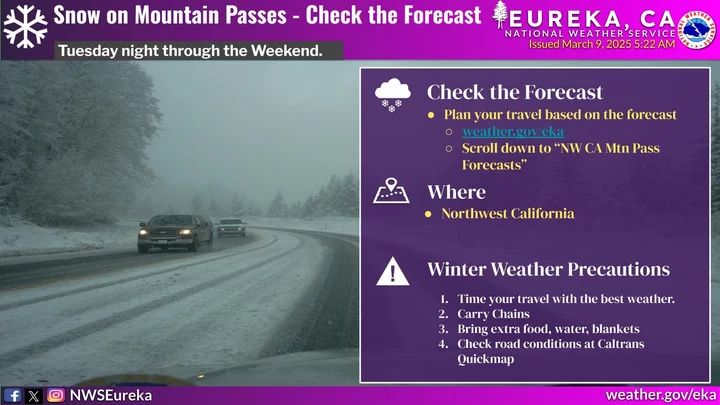

Also: Snow! Looks like there will be plenty of snow sticking in the mountains, very possibly including on highways heading east from the coast. Stay vigilant, motorists!

(Source)

BOOKED

Today: 6 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Us101 S / Fields Landing Ofr (HM office): Provide Traffic Control

Tompkins Hill Rd / Hookton Rd (HM office): Trfc Collision-Unkn Inj

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Two-Vehicle Crash Blocks Lanes at G Street and Samoa Boulevard in Arcata

RHBB: Harbor Lanes Temporarily Shut Down by Health Officials, Reopens After Fixes

RHBB: Highway 1 Buried by Landslide South of Elk; Road Fully Closed with No Reopen Time

RHBB: Eel River at Fernbridge Crests at Highest Level in Five Years; Moderate Flooding Reported in Delta

Bipartisanship Is Rare in the California Legislature. Here Are the Bills Breaking the Divide

Ryan Sabalow / Monday, March 10, 2025 @ 7:30 a.m. / Sacramento

Lawmakers gather during the first Assembly floor session of the year at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Jan. 6, 2025. Less than 1% of bills introduced so far have bipartisan authorship. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters

###

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

In these hyper-partisan times, Democrats and Republicans can’t seem to agree on much. That includes the members of the California Legislature.

Of the 2,278 bills lawmakers submitted by the deadline last week, only 11 had Republicans and Democrats as joint lead authors, according to a CalMatters analysis of the Digital Democracy database.

Another 41 bills had bipartisan “co-authors” and “principal co-authors,” designations that are more symbolic since a bill’s lead authors and their staffs are expected to marshal the legislation through to the governor’s desk.

Authors and co-authors can still be added to bills later in the year. But taken together, these early bipartisan bills represent less than 1% of all the legislation filed so far this session. The figure perhaps isn’t surprising, given ever-rising partisan acrimony and Democrats having a supermajority in the California Legislature.“You know, at the end of the day, we as Democrats also represent a significant portion of Republicans, as well as no party preference, as well as independents and much more,” said Sen. Aisha Wahab, a progressive Democrat from Fremont who co-authored a bill this year with Republican Sen. Kelly Seyarto of Murrieta.

Wahab’s Bay Area district is only 15% Republican and she said she and Seyarto don’t agree on many other issues. But she liked his bill, a version of which failed last year, to help police recruitment efforts by giving officers more time to finish new mandatory college requirements.

California’s early bipartisan bills

So what other other issues do California Republicans and Democrats agree on enough this year to work together?

At least four of the bills with bipartisan joint lead authors were “spot bills,” placeholder legislation that allowed the lawmakers to get their bill in at the filing deadline. The details of those measures on tax penalties, waste management, government ethics and local courthouse funding will be added in coming weeks.

Other bipartisan measures include a health care proposal, Senate Bill 246 by Sens. Anna Caballero, a Democrat, and Shannon Grove, a Republican. The bill would expand Medi-Cal funding for training programs to help address physician shortages including in the San Joaquin Valley, which the two senators represent.

Another public safety measure, Senate Bill 264, by Democratic Sen. Sasha Renée Pérez of Glendale and Republican Sen. Suzette Martinez Valladares of Lancaster would allow prosecutors to charge people with felonies if they impersonate police or firefighters in order to gain access to disaster areas. Currently, the maximum penalty is a misdemeanor. The bill comes after several people were arrested for allegedly impersonating firefighters following the Los Angeles County wildfires.

At least two other bills seek to resurrect legislation that stalled in previous sessions.One was Senate Bill 458 by Sacramento County Republican Sen. Roger Niello and Democratic Sen. Tom Umberg of Santa Ana that would require the Legislative Analyst’s Office to write ballot initiative titles and summaries instead of the partisan Attorney General’s Office.

Various efforts over the years to make the change have fizzled out.

First: State Sen. Thomas Umberg during a Senate floor session at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Feb. 20, 2025. Photo by Fred Greaves for CalMatters Last: State Sen. Roger Niello during a floor session at the state Capitol in Sacramento on Aug. 29, 2024. Photo by Florence Middleton, CalMatters.

The issue took on new life last year after Republicans, including Donald Trump, sought to portray Kamala Harris as a soft-on-crime liberal who supported 2014’s Proposition 47, an initiative that reduced sentences for some offenses (and that voters partially overturned with Proposition 36 in November). Harris was attorney general in 2014 when her office wrote the summary that appears in the state’s Official Voter Information Guide, but she stayed neutral and didn’t officially endorse the measure.

Niello carried a similar bill in 2023 without any Democratic coauthors. He said he was thrilled when the bill passed the Senate Elections Committee with unanimous support, but he was disappointed when it died without another hearing.

“It was most certainly a leadership move, but the fact is, I got it out of the election committee with a unanimous vote, so I thought, ‘Hey, I’m making progress here,’ ” he said.

He said he approached Umberg to join him as lead author of this year’s measure in the hopes the bipartisanship would help move it to Gov. Gavin Newsom’s desk.

For his part, Umberg said he knows Niello well and trusts and respects him. Plus, he said the proposed change is “good public policy.”

Can bipartisanship reform ADA “shakedown” suits?

A pro-business measure, Senate Bill 84, is another example of how Niello’s relationships with his Democratic colleagues led to bipartisan legislation that seeks to resurrect a dead bill.

For decades, California businesses have complained that they’ve been shaken down by aggressive law firms that demand payment when they identify violations of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). Such violations could be a mirror, countertop or handrail being a fraction of an inch too low or too high.

Niello last year carried a bill to give businesses with fewer than 50 employees 120 days to comply with ADA rules before they have to pay the law firms that identify the problems.Niello’s previous bill made it through the Senate, but it died in the Assembly. This year, he hopes having two Democratic senators, Caballero and Angelique Ashby of Sacramento, as lead authors from the beginning will help to persuade their colleagues.“This has been affecting a lot of businesses in disadvantaged areas in Democrats’ districts,” Niello said.Like Umberg, Ashby said that when it came to working with Niello, it didn’t take much convincing.

State Senators Angelique Ashby and Aisha Wahab during a press conference in support of Senate Bill 1043 at the Capitol Annex Swing Space on April 15, 2024. Paris Hilton spoke in support of SB 1043, which would require more transparency for children’s treatment facilities that are licensed in California. Hilton spoke of her traumatic experience during her teenage years at similar facilities in California and Utah. Photo by Miguel Gutierrez Jr., CalMatters

For one thing, she said she’s had “microbusinesses” including a popular burger joint in her district struggle over ADA-compliance claims.Ashby said she also knows Niello personally from her time as a member of the Sacramento City Council. Niello is a former Sacramento County supervisor and a former chamber of commerce leader whose family owns a number of car dealerships in their districts.

“He’s a wonderful human,” Ashby said. “We don’t have to agree on every policy issue to like each other, and we do.”

Two moderate former Democratic lawmakers who left office last year say those sorts of relationships can be critical to advance tough bills. Plus, they argue that when Republicans support Democratic proposals, it can add credibility in the eyes of the public.

“It can make your proposed policy change stronger and more enduring,” said Steve Glazer, a former Democratic state senator from Orinda who didn’t seek reelection last year.

Steven Bradford, a Democratic state senator from Inglewood who termed out last year, recounted how he needed Republican support on a bill that expanded powers for the police that patrol Los Angeles airports since he didn’t have enough Democratic votes.

“Had I not had the relationships with those guys, that bill would have died,” he said.

###

Digital Democracy’s data analysis intern, Luke Fanguna, contributed to this story.

TO YOUR WEALTH: How Emotional Investing Can Cost You Money (And 5 Ways to Minimize It)

Brandon Stockman / Sunday, March 9, 2025 @ 7 a.m. / Money

We used to live in a culture that suppressed emotions. Think John Wayne.

Now we live in a culture that expresses emotions. Think crying videos on TikTok.

This goes for the economy too.

Svend Brinkmann, a Danish philosopher and psychologist, leaning on the work of sociologist Eva Illouz who coined the term emotional capitalism, defines it as: “a culture of emotions, in which feelings play a significant part in personal transactions between individuals.”¹

This may be the case in corporate America and in our service economy, but feelings can be problematic if they lead an investor’s decisions about investing.

Expressing your authentic self about the stock market can be the worst thing you can do.

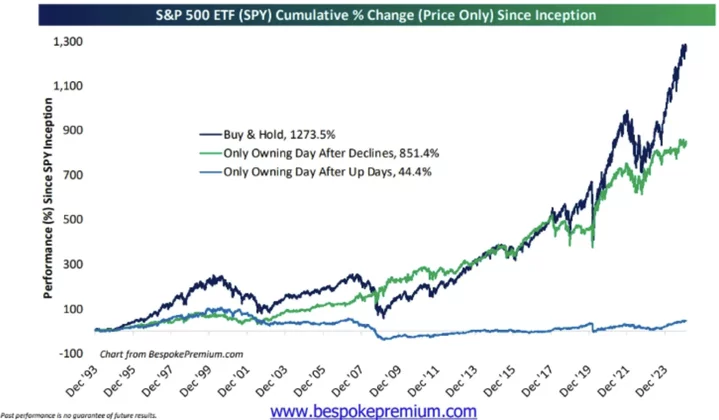

Bespoke research shows that since the 1990s only buying after down days has been far more profitable than only buying after up days.²

The reward of feeling bad after a down day and buying anyway, compared to the cost of only buying after an up day when you felt better, is stark.

Like by hundreds of percentage points.

This validates Warren Buffett’s famous line about trying to time the market in his 2004 letter to shareholders: “…if they insist on trying to time their participation in equities, they should try to be fearful when others are greedy and greedy only when others are fearful.”³

The thing is, when everyone else is fearful, it’s easy to be fearful, and when everyone else is greedy, it’s easy to be greedy. We all experience FOMO and loss aversion.

And we humans love a crowd.

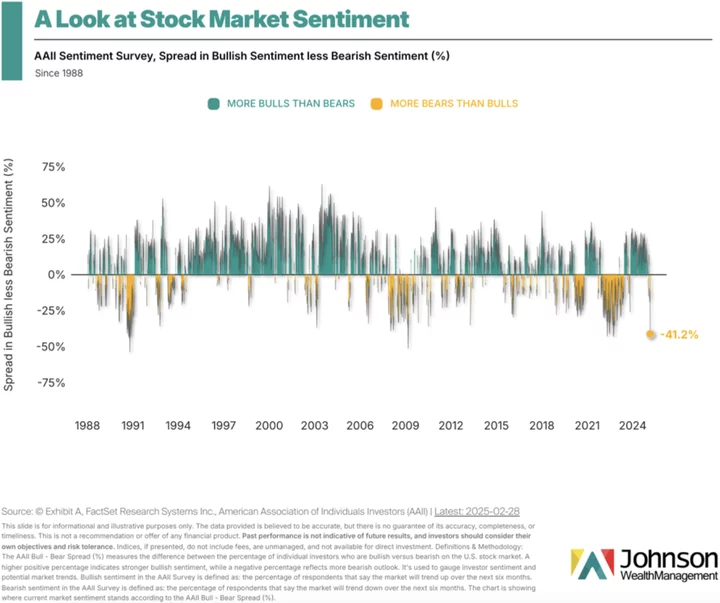

Recently, the crowd has mostly negative feelings about the stock market. Between concerns about tariffs and a drastic drop in potential first quarter GDP estimates over at the Atlanta Fed⁴, some market participants are spooked. This is captured in one popular survey from the American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) that shows the spread in Bullish sentiment (the stock market will go up!) less Bearish sentiment (the stock market will go down!).

Translation: there are a lot more bears than bulls right now.

Does that mean the stock market will drop significantly? Maybe.

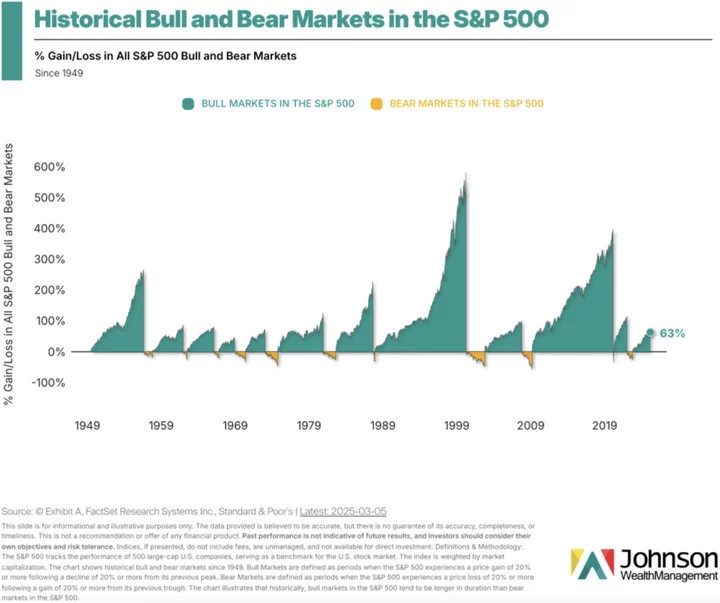

It should surprise no one when stocks go into a bear market (20% or more drawdown), as those have occurred over the past 150 years an average of every six years.⁵ If you only go back to the year that preceded the Great Depression, it’s an average of every four years.⁶

Therefore, if you don’t have an investment portfolio that can handle a bear market, you likely do not have the right portfolio.

Write that down. Put it on a sticky note next to your monthly statement or plaster it on your wallpaper on your computer.

The good news is that bear markets are often much shorter than bull markets.

Bearish sentiment can also be contrarian. Emotions can have an inverse relationship to stock market returns.

Sometimes when there are a ton of people negative about the stock market, the forward returns for the stock market can be quite good. For example, there are around 60% bears in that sentiment reading, which is quite high historically, and when that occurs, investment returns a year later can be quite good: up a median of 17.8% since 1990.⁷

How do you guard against the very human tendency to live by your emotions as an investor?

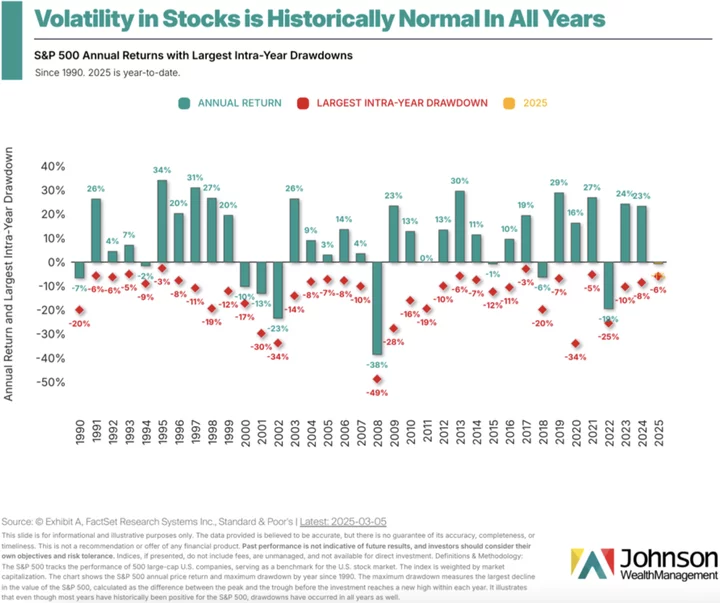

First, discipline yourself to remember that the market is volatile. This is easy to remember when stocks are falling, and not so easy when stocks are up. Don’t forget: volatility itself is the subscription price you pay in the stock market for investment returns.

Second, curate your media consumption. Don’t let the algorithm of your social networking or your favorite news channel dictate your investment decisions. Our willpower is often weak, and if your diet is constant fear, clickbait, and political bias, your portfolio may experience heartache.

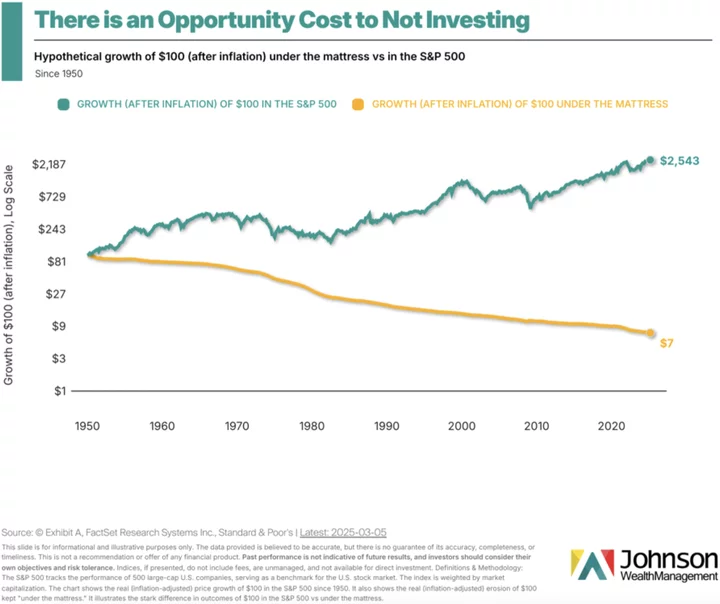

Third, invest according to your time horizon. If you need money quickly, the stock market can be a very dangerous place. If you are looking to beat inflation over the long term and don’t need it for many years, it has been one of the best places for investors’ money.

Fourth, consider automatic investing and dollar cost averaging in your financial plan. If it’s automatic, you will buy whether you feel like it or not and capture the dips, highs, and all the spots in between of the market over time.

Fifth, partner with a financial advisor that you trust. Those last three words are far more important than just hiring any financial advisor. Talk to people you trust about who they use. Look up the wealth advisor’s background through brokercheck.finra.org or adviserinfo.sec.gov. Ask a bunch of questions when you meet with the professional. Sometimes the best way to manage your emotions for you and your family’s financial journey is having someone help.

Emotions aren’t bad.

They are a gift.

But allowing them to govern your investment decisions can be financially disastrous.

###

Sources:

- “Stand Firm” (Polity Press, 2017), p. 64.

- Chart from Sam Ro’s column “It’s OK to have emotions—just don’t let them near your stock portfolio 📉” published March 2, 2025. Accessed online: https://www.tker.co/p/stock-market-performance-after-down-days

- Accessed online: https://www.berkshirehathaway.com/letters/2004ltr.pdf

- Accessed online: https://www.atlantafed.org/cqer/research/gdpnow

- “What Bear Markets Mean for You and Your Money”, published by Fidelity Smart Money on August 14, 2024. Accessed online: https://www.fidelity.com/learning-center/smart-money/bear-market

- “How Often Do Bear Markets Occur?”, published by Ben Carlson on February 11, 2024. Accessed online: https://awealthofcommonsense.com/2024/02/how-often-do-bear-markets-occur/

- Published 2/27 on X by Ryan Detrick. Accessed online: https://x.com/RyanDetrick/status/1895107530931474799/photo/1

###

Brandon Stockman has been a Wealth Advisor licensed with the Series 7 and 66 since the Great Financial Crisis of 2008. He has the privilege of helping manage accounts throughout the United States and works in the Fortuna office of Johnson Wealth Management. You can sign up for his weekly newsletter on investing and financial education or subscribe to his YouTube channel. Securities and advisory services offered through Prospera Financial Services, Inc. | Member FINRA, SIPC. This should not be considered tax, legal, or investment advice. Past performance is no guarantee of future results.

OBITUARY: Raven Dushay, 1960-2025

LoCO Staff / Sunday, March 9, 2025 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Raven

Dushay

February

5, 1960 — February 15, 2025

Just before midnight on February 15, 2025 our dearest Raven gained her wings and took flight to the spirit world.

Raven was a deeply compassionate and caring soul with a remarkable life.

She started her life as Winnie Laure Weinshank in the City of Lost Angels.

She had a rough family life with a dad who was a gambler, two brothers, and a mom who was kind and compassionate.

The family moved frequently and Raven found her friends and solace in the trees in the backyards. She also found strength in her jiu-jitsu class and at the age of 12 she left home to make her own way. By then she was a black belt known as “Baby Black Belt.” She lived on the streets and met many interesting characters.

At a young age she gathered her only belongings: overalls, boots, a backpack, and a flute. A German shepherd named Freedom adopted her and they hitchhiked around California. Like the Joni Mitchell song, “and we’ve got to get ourselves back to the garden,” she set her goal on getting out of the city and moving to the country to create a self-sufficient lifestyle. She joined the seasonal workers moving from community to community picking apples, and planting and trimming trees. On her way to a Rainbow Gathering she ended up in Garberville, where she met Paul Zucchini under a bridge. He told her about a community called Whale Gulch on the rugged Lost Coast of Mendocino County. At the age of 18 she finally made her way to a trade fair in Whale Gulch where she joined the group of women dancing in the meadow and they became lifelong friends.

For her 19th birthday she was gifted an EMT course by Nancy Peregrine. This started her on the path to nursing school and a long career in nursing where she touched the lives of many. She worked in the emergency department at St. Joseph Hospital, Redwood Memorial Hospital, and Mad River Hospital. She also provided post anesthesia care, and even completed medical missions to Haiti. With a special ability to connect with people on a deep level, Raven was never afraid to help the most vulnerable and down and out. She was a survivor of abuse and was a fierce advocate for those who were suffering and in need of a helping hand. Her twinkling eyes and effervescent smile would light up the darkest corners of our world.

Raven would teach you self defense, buy you your first vibrator, deliver your baby, tend to your wounds, rescue you, teach you CPR, and be by your side in life and death.

A great adventurer, a mischief maker, an inspiration starter. A mother, a friend and sister to many, a yenta, a musician, an artist, and a bright light. Her love ripples far and wide. Raven leaves behind a large community of friends and family. We will hold her in our hearts forever.

How Raven got her name:

”I was laying down next to the Eel River and there were these Ravens dancing in the sky. I just felt like I was flying with them and was inside their bodies looking down at the river through their eyes. Later that week I was volunteering for an environmental protection group that was protecting the whales in Port Townsend. I walked onto the boat and a gorgeous woman captain says “Raven?” I said, yes. She goes, yeah, I thought so. You look like a fair Raven spirit to me.“

Raven’s Celebration of Life — All are welcome

Sunday,

June 8, 2025

3

p.m. - evening

Dinner main course provided (Mexican food). Please bring a side dish, salad, or dessert to share.

Bring your own beverage of choice (alcohol is allowed). Water, coffee and tea provided.

Please bring an instrument if you wish.

Location:

River

Lodge

1800

Riverwalk Dr, Fortuna, CA 95540

Please R.S.V.P. and let us know if you would like to volunteer to help with the event. R.S.V.P. here.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Raven Dushay’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Hundreds Show Out to Protest at the County Courthouse

LoCO Staff / Saturday, March 8, 2025 @ 12:57 p.m. / Activism

Hundreds of Humboldt County people are spending their some of their International Women’s Day at the courthouse this afternoon, lining both sides of Fifth Street to protest actions taken by the Trump Administration. The above video gives you some sense of the scale of the gathering.

There are signs supporting federal workers, women’s rights, social security benefits and general human decency, among other things.

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Trump Has Gutted NEPA. What Does That Mean?

LoCO Staff / Saturday, March 8, 2025 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Image: Stable Diffusion.

The Trump Administration has taken a large whack at the National Environmental Policy Act (often better known by its acronym, NEPA). NEPA is the federal environmental law that requires that the federal government understand and acknowledge the environmental impacts of its actions and provide an opportunity for public engagement on projects.

While a bedrock federal environmental law, the law itself is vaguely worded. Thus, implementing regulations (issued by the Council on Environmental Quality in 1978) have been important to its application. Through these regulations, we have NEPA as we know it — “major federal projects” and “cumulative impact analysis” and so on. All that changed on January 20th. Through Executive Order, Trump revoked the authority of the Council on Environmental Quality to issue regulations and the agency has withdrawn the long-standing rules. Now we are in a legal limbo: NEPA still exists (Trump can’t veto a law that has already been approved) but the rules implementing NEPA are gone. What are we to do?

Jan Hasselman of Earthjustice and Melodie Meyer of EPIC join the program to discuss this major turning point in federal environmental law.

###

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: The ‘Sporting Girls’ of Old Town in the Golden Days of Eureka’s Prostitution Industry

Glen Nash / Saturday, March 8, 2025 @ 7:30 a.m. / History

Before I get into the story of “night life in early Eureka,” I want to describe as best I can the way Eureka looked from its beginning to the 1930s.

In the early 1850s, the City of Eureka was started in a small clearing in the redwood forest that grew right down to the bay. The first settlers lived in tents and small shacks. This land was not very level; it sloped back up inland and was crisscrossed with many deep gulches and sloughs (most are no longer in existence in that they have been filled in and built over with streets and homes).

The town was built along the bay with wharves built for ships to tie up. The only method of transportation to the bay was by ship and, likewise, everything was brought to the area by ships.

The streets were laid out north and south, east and west. First Street ran east/west along the bay; Second Street was next; then Third. The streets running north and south started with A Street and continued with B, C and so on.

The main stores were located along Second Street. The first Pioneer School was built on the southwest corner of Third and G streets. Children were not allowed to walk down to First and Second streets as there were many saloons and “bad elements” down there. The first church (Congregational) was constructed on Fourth and G streets and was right up against the redwood forest.

Eureka grew slowly during the next 60 years. By 1910 there were three manufacturing brickyards in Eureka, and four redwood saw mills and shingle mills. Lumber, along with good gravel and sand bars, and a good water supply made for readily available building materials.

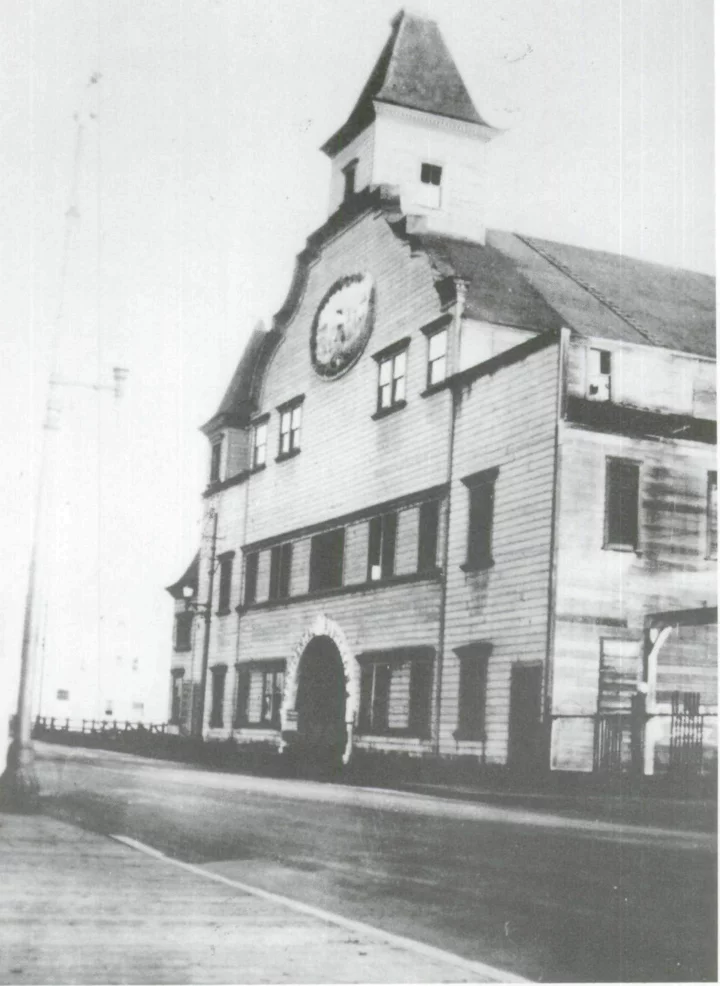

The Occidental Pavilion, located at Second and A streets in Eureka, was torn down during October and November of 1940. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

Eureka had built a beautiful courthouse, a city hall, several large buildings, theatres, banks and business houses. There were eight new large school buildings built throughout the town, along with several large hotels, including The Vance. The Armory Hall, where boxing matches were held, was on the northeast corner of Second and C streets and still stands today. Almost all of these buildings were located between Fourth Street and the bay. The Occidental Pavilion, a very beautiful, large building located at Second and A streets, was for many years used for fairs, carnivals, dances, banquets, plays, rollerskating, boxing matches and other activities.

In 1887 a horse-drawn streetcar system began in Eureka. In 1903 an electrical streetcar system was installed. This street railroad covered the main parts of Eureka until 1940 when it was abandoned in favor of a bus system.

Streets were graded and graveled, and sidewalks were built of redwood planks (there was very little street pavement or cement sidewalks until the 1930s). In 1914 the railroad to the south was completed, which helped development by making it easier and faster to come to Eureka.

Eureka was a seaport and logging town from the very beginning — a real working man’s town. As a result, soon came the “sporting girls.” These women worked in the dance halls, saloons and cabarets — places where the men and their money hung out. Eureka had more than its share of saloons, gambling houses and dance halls. In short, it was a “wide-open” town. In the 1800s, women working in the saloons enticed men to buy drinks. The woman might then invite him up to her room upstairs for a party and, if the man passed out, he would be relieved of his money, then tossed out.

In the 1920s there were several cabarets in Eureka, including the Blue-Bird Cabaret at 100 F St.; the Louvre, upstairs at 240 Second St.; the Woodland, 503 Second St.; Young’s Cabaret, 317 Second St.; the Olympia, First and E Streets; and the Dreamland Dime Dance Hall, upstairs at 325 Second St.; these cabarets employed about 25 women each. This Second Street was where the action was.

Kittie Farris’ Joy Emporium is pictured here on the corner of Second and D streets in Eureka, c. 1882. Photos via the Humboldt Historian. [Ed. note from 2025: The building still stands. Compare its current name to its original one.]

In these cabarets and dance halls there was always someone selling tickets at 10 cents apiece. These tickets were good for one, very short, i.e. two-minute, dance with your favorite girl. She would turn these tickets in at closing time and collect her pay for them. A good dancer and good company could make out pretty good. The woman would always ask you to buy her a drink, however, hers would be soda water even though you paid for an alcohol-loaded drink. The women got credit for the drinks they sold.

Most of these working girls were good looking and good conversationalists; they also dressed well. Just like anyone else, they had to make a living. Some were married and they took this job to supplement their husbands’ meager lumber mill salary.

A good many of these sporting girls had rooms over C.V. Jackson’s Store at Second and E streets, or other rooming houses down in that part of town. Some would make dates, meeting after the dance hall closed for the night. Some might turn a few tricks for a price if a man had the money.

Before you pass judgment, remember there were no food stamps, welfare system. Social Security or unemployment checks in those days; if you did not work, you did not eat. The system apparently worked as there were no homeless women on the streets.

The cabarets were very popular places, not only with the loggers and seamen, but also some of our local, prominent men who patronized these places. They, of course, did not tell their wives.

These dance halls and cabarets had some very good, small bands playing for the dances; many musicians got their start in these places. The performers received a few dollars for each night’s work.

Before Prohibition, whiskey, wine and beer flowed freely in Eureka’s saloons, gambling rooms and cabarets. With the passing of the Volstead Act in 1919, the country was required by law to be dry. But, as we well know, bootlegging whiskey and other spirits ran rampant not only in Eureka but throughout the nation. In all of the alcoholic drinks sold, it was bootleg whiskey, wine or beer that provided the punch.

The local “dry squads” and law enforcement officers were constantly raiding the various saloons and other spots, called blind-pigs or speakeasies, to catch anyone selling bootleg booze. The authorities did not have great success trying to control this activity.

This bootlegging went on for 13 years, up until ratification of the 21st Amendment in December 1933. During Prohibition the entire nation was in trouble with gang warfare over the bootlegging activity. Many murders by rival gangs were reported in the large cities of the country.

Whiskey was made throughout Humboldt County with many stills in the surrounding woods and mountains. Most of this “moonshine” corn whiskey sold by the bootleggers to the blind-pigs below Fourth Street went for $6 or less per gallon, depending upon the quality. Moonshine was sold in five-gallon tin cans. If not properly distilled, it could become poisonous, causing blindness, even death.

During the late summer, many truckloads of grapes from the south were delivered to various establishments along First and Second streets. They surely did not eat all these grapes, rather, they made them into wine to sell. This illegal wine, called “Dago-red,” could be quite good.

Many local people made home-brew beer, some of which was good, some terrible, all of which was against the law.

There were many arrests of bootleggers in Humboldt County, and some skulduggery amongst local county officials over bootleg whiskey. Some even went to prison over this. A portion of the confiscated booze disappeared from the storage room in the Humboldt County Courthouse. There was no shortage of thieves who would hijack the booze from the bootlegger, then sell it.

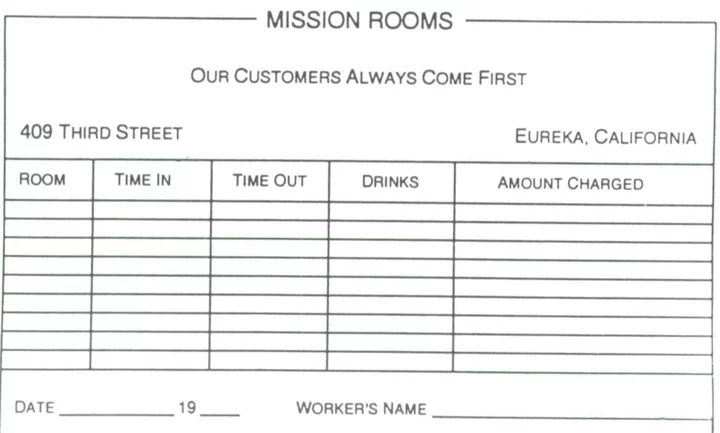

A time card used by the workings girls at Mission Rooms, 409 Third Street.

During this time there were many rooming houses in the area covered by A Street east to J Street and from Fifth Street north to the bay. Almost all of the two-story buildings in this area had “rooms” signs hanging in front. Most of these rooming houses were brothels, occupied by an older woman, called the madam, and her girls. The madam would see that proper decorum was maintained by the customers and working girls living there. She would be in charge of operations, collect a share of the money for the house and keep track of tricks turned by the women. The working girls kept timecards each night showing the number of drinks sold and tricks turned. These were turned in each night to the madam along with her cut of the take. These houses had from two to five women each. These “ladies of the night” would entertain loggers, seamen and many local men by selling drinks and other “services.” These places also doubled as blind-pigs where moonshine booze, whiskey, wine or beer could be bought.

This advertisement appeared in a 1903 brochure. “The Place,” located in the alley between F and G streets, and Second and Third streets, was most certainly a brothel.

These establishments would open for business in late afternoon and close at two or three in the morning. They sometimes stayed open all night, especially on Saturday nights when hundreds of loggers came to town on the logging trains. At other times there were several large freight and passenger ships in the harbor, bringing many sailors who had their pay to spend — and spend it they did.

Most of these houses had a small light hanging over the entrance, often red in color, hence, the name “Red Light District.” The stairs leading up to these rooms usually had one of the steps wired which, when stepped upon, would ring a buzzer in the madam’s room. This alarm enabled the residents to stash the booze in case of a raid by the “Dry Squad.” They knew when someone was coming up the stairs, friend or foe.

The local taxi cab drivers knew the location of all these places in Eureka. They had agreements with the madams for a cut of the take from the customers they would bring to their rooms. Strangers in town always asked the cabbies for directions and the cab drivers would ask a male visitor if he wished to see a woman. If the answer was “yes,” the cabbie would escort the man to one of these places.

Some of the women had boyfriends, called pimps. These fellows were often bartenders or cardsharps playing in local gambling establishments, or involved in doing some other menial task around town. They would inform other players or lonesome men of a place where they might find a woman who would show them a good time. These pimps would collect their share of the money from the women. During the 1920s and 1930s, the going price of a trick was $2. During the Civilian Conservation Corps days, the price paid by these C.C.C. boys was $1.50.

These “ladies of the night” patronized many of the local stores, paying cash for whatever they purchased. Many of them purchased the best clothes and shoes from Daly Brothers Big Store and other well-known establishments in Eureka. Most of them purchased their cosmetics, perfumes and medications from the Pacific Pharmacy on Second and F streets. The Eureka merchants had nothing but good words for these working girls as they were good paying customers. They never acted smart or sarcastic and never caused trouble, which was remarkable considering they had to deal with a lot of drunken, mean men.

If one of these women met a customer on the street the following day, she would never show any sign of recognition. Therefore, many of Eureka’s married men had nothing to fear in meeting these women on the street.

These sporting girls had examinations every two weeks by a local physician, either Dr. Carl Wallace or Dr. Sam Burre. Consequently, there was no epidemic or venereal disease in Eureka. If a case of venereal disease was brought into town by some out-of-town person, it was very soon detected by these doctors and taken care of.

These women did not need to solicit customers on the streets as they had plenty of walk-ins. Sometime they would beckon from their upstairs window to men passing by, inviting them to “come up and see me sometime.” They would usually sleep in until noon or later.

In 1949 the local Elks Lodge #652 started a drive to help the local Blood Bank. Eureka was divided into sections, with members delegated to sell tickets in each section. Four well-known members had the section from A Street east to J Street and from Fourth Street north to the waterfront. These four men sold more tickets and collected more money from the 35 local brothels in that section than all of the rest of the men collected in the entire city. These women were apparently very willing to help other people.

At Christmas time in Eureka, the Salvation Army could always count on these girls for large donations for the poor people, children and down-and-outers.

The Eureka Volunteer Fire Department would always sell more tickets to the Firemen’s Ball in this area than all the rest of Eureka — yet the girls never attended the party.

Many of these women had stories they could tell that would make the ordinary person’s blood run cold: abused childhoods, rapes, failed marriages, bad company, broken families. There were many reasons for their plight.

This oldest profession in history was very much a part of the history of Eureka and Humboldt County during the early 1930s. A count once made of the number of women following this profession in Eureka claimed over 250. There were well-known houses on the Humboldt Bay beach near the mouth of Elk River, the Old Triangle Road House on Elk River Corners, Johnie Wood’s Hotel at Freshwater Corners, and many such houses at Rio Dell and other places around Humboldt County.

Fire broke out in the Splendid Cafe in 1950. Upstairs were the Mission Rooms, Third and E streets. A small park now stands there, across from the Clarke Memorial Museum.

“The best little whorehouse” in Eureka was upstairs over the Mission Cigar Store on the northeast corner of Third and E streets, across E Street from the Clarke Museum (there is a park there today). A pretty woman called Jackie was the madam.

There was also the Alpine, Atlas, Carlton, Chester, Denver, Eureka, Gordon, Mecca, Royal, Ruby and Star Rooms. Mattie Well’s Hotel, Kitty Ferris’ Joy Emporium, the Model Rooms, Popular Hotel and Rex Rooms comprised some of the 30 or so places in Eureka. Most never had names and were just “rooms.” Some had entrances from the alleys and no numbers. A few are still standing today.

There was an African American house. This house, located on Summer Street between Fifth and Sixth streets, was operated by a black madam. She later opened a barbecued sparerib house at another location. She and her husband also catered banquets and receptions, and did a fine job.

It seems that much of gambling, card rooms, slot machines, punch boards, prostitution, bootlegging, speakeasies and other illegal operations were controlled by certain men in the area during these rough days. Sometimes referred to as the “Mafia,” these men were well known and made their fortunes in this business.

In 1942, during World War II, Eureka Mayor H.R. Simmons received orders from U.S. Army Headquarters to close the houses of prostitution, at least for the duration of the war. The mayor called a special meeting of the Eureka City Council and the city officials decided to follow orders. They tried…but were not very successful. Some of these displaced women obtained jobs at the Chicago Bridge and Iron Dry Dock Plant at the foot of Washington Street where they fared well at their new trade.

In the early 1950s there was a statewide movement outlawing this “social evil” and street-walking throughout the state. The mayors of Eureka, John Langer followed by Robert Madsen, followed this law and closed most of these places — or at least tried. They sent local police to raid these houses and arrested all offenders, both hookers and clients. A good many citizens did not approve of this action.

Many absurd aspects to this story exist: One night, during a raid of one of these houses by police, the officers discovered a prominent local businessman hiding unclothed in a closet, a very embarrassing situation for him. His name was never printed but word got around.

The windowpane broken by a brick which fell through June 6, 1932, during a 6.4 earthquake (a woman was killed by the brick as she lay in bed).

During the violent earthquake of June 6, 1932, when many chimneys were damaged in Eureka, bricks fell off the chimney of the Carson Building at Third and F streets into the alley between Second and Third streets. One brick crashed down through a window in a building on the other side of the alley, killing a woman in bed in this rooming house. The break in the window where the brick went through left a perfect silhouette of a woman’s head; a photograph of this phenomenon appeared in a local newspaper.

During November 1932, this writer was a young carpenter working for a contractor who had a contract to build a new, modern building on the north side of Second Street between C and D streets. This building was designed for a cardroom and “blind-pig” operation, complete with hidden trap doors and sliding panels for hiding booze. The second floor was designed for a brothel with several small bedrooms and, of course, a wired step in the stairway. I remember a very pretty blond lady coming by every few days in order that she might see how her new “house of pleasure” was coming along. She went by the name “Sugar.” It was said she got married and left the profession, but the building is still there.

There are many stories that can and cannot be told of incidents that occurred in these places during these times, so many that a rather colorful book could be written about the early history of the old “Downtown Eureka.”

###

The story above is excerpted from the May-June 1993 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.