(VIDEO) New Documentary ‘Guardians of a Forgotten Warship’ Spotlights Humboldt Veterans Working to Restore a WWII-Era Vessel Beached in Samoa

Isabella Vanderheiden / Monday, Nov. 11, 2024 @ 8:53 a.m. / Our Culture

###

“Guardians of a Forgotten Warship,” a Cal Poly Humboldt student documentary highlighting a group of local veterans, has been selected to screen at the 2024 Veterans Film Festival in Los Angeles.

The five-minute documentary, directed and produced by Ray Olson of Humboldt Outdoors, tells the story of six dedicated veterans who have taken on the tremendous task of restoring the USS LCI(L)-1091 – affectionately known as Ten-Ninety-One – a World War II-era warship beached on the Samoa Peninsula.

Before it arrived here in Humboldt County, LCI(L)-1091 took part in the Battle for Okinawa in 1945, witnessed atomic bomb tests at Bikini Atoll and served as a medical lab during the Korean War to help prevent the spread of wartime disease. In 1988, landing craft infantry veteran Ralph Davis bought the historic ship and renamed it Ten-Ninety-One. Davis used the ship as a fishing vessel for 17 years before he donated it to the Humboldt Bay Naval Sea/Air Museum with the hope that it could one day be restored. The ship sat in Humboldt Bay for another decade before it was dragged ashore to its current location behind the Samoa Cookhouse.

Twice weekly, the Ten-Ninety-One crew climbs aboard the historic ship to battle the ever-present threat of rust, tackle leaky areas of the top deck, touch up the paint, weld new deck plates and work on various other repairs.

“It’s definitely a labor of love,” U.S. Airforce veteran Royal McCarthy said in an interview with the documentary crew. “[W]e don’t want to see this thing go away, and we don’t want to see it rust into nothing. We definitely don’t want to see it cut up for scrap, so we’re doing all we can to promote the longevity of the boat and to make sure it’s saved.”

If the crew can’t find a new location for the ship, it will be scrapped to make way for the Humboldt Bay Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal project, which aims to convert the Redwood Marine Terminal I property into a state-of-the-art industrial site for manufacturing, assembling and exporting the massive components needed for offshore wind development on the West Coast.

Relocating the ship would cost an estimated $50,000, which is “far beyond” the crew’s financial resources, according to Olson. The crew’s dream is to replace the bottom of the ship, lug it back into Humboldt Bay and turn it into a museum and a meeting place for veterans. However, doing so would cost another $1 million dollars.

“It’s a long shot – I know it’s a long shot – but that isn’t going to stop us because the mission is to save the ship,” said U.S. Army veteran Ron Matson. “If we don’t, they’re going to cut it up into little pieces, which would be a travesty.”

“Guardians of a Forgotten Warship” was produced by Olson as a class assignment for Cal Poly Humboldt’s film class “Documentary Film Production” with help from Toni Brown, Solomon Winter, Tyler McNally and Jake Stoll.

“‘Guardians of a Forgotten Warship’ embodies everything we hope for in the documentaries our students create,” Dave Janetta, an assistant film professor at Cal Poly Humboldt, wrote in a statement to the Outpost. “We encourage them to tell local stories that resonate widely and bring awareness to issues that need attention. … It’s incredibly rewarding to see our students apply the lessons of the classroom to real-world projects in the community and have the opportunity to share their work with a broader audience.”

The documentary will screen at the Bob Hope Patriotic Hall in Los Angeles on Friday, Nov. 15.

###

BOOKED

Yesterday: 5 felonies, 5 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

Sr96 / Kings Crk (YK office): Car Fire

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Humboldt Ranks Among Highest in State for CARE Court Referrals Despite Funding Gaps

RHBB: California Attorney General Urges U.S. Senate to Reject SAVE America Act

RHBB: Major Roadwork Scheduled Friday, February 20 through Thursday, February 26

The Oregonian: Radical Oregon animal rights initiative moving closer to qualifying for ballot

OBITUARY: Jason ‘J-Bird’ Hunsucker, 1975-2024

LoCO Staff / Monday, Nov. 11, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Jason “J-Bird” Hunsucker

February 28, 1975 – November 4,

2024

Jason “J-Bird” Hunsucker, 49, a devoted family man and cherished member of the Yurok community, passed away on November 4, 2024, in Notchko on the Yurok Reservation.

Born in Crescent City to Gael Stallings and Bruce Hunsucker, Jason lived his entire life on his ancestral homelands in Wautec. Known for his kindness and generosity, Jason was a beloved presence among family and friends. He was the heart of family gatherings, bringing everyone together with his laughter, his big spirit, and his love for a good time.

Jason found joy and peace in the great outdoors. An avid hunter and dirt bike racer, he loved camping and riding motorcycles. He was always ready to give to others, from deer and elk to fish, ensuring his family and community were well cared for. Jason loved being Peech-o-wos. He went above and beyond for his grandchildren and made sure to create as many memories with them as he could. He cherished every moment spent with his children, grandchildren, nieces, and nephews, creating lasting memories playing with them as babies and celebrating their lives as they grew.

Working with the Yurok Tribe, Jason took great pride in his role, thriving in his work and strengthening his deep connection to the community he loved. He was happiest by the river, swimming in its cool waters and reveling in the beauty of the land.

Jason is preceded in death by his paternal great-grandparents, Frances and Stokes Jaynes; paternal grandparents, Patricia (Frye) and Bruce Hunsucker; uncles, Jack George and Bob Hunsucker; and cousin, Fred Scott. On his maternal side, Jason is preceded in death by his great-grandparents, Marian and Urban Stallings, Rachel and Carl Oliver, and his maternal grandparents, Lawrence and Greta Stallings.

Jason is survived by his loving mother, Gael Stallings, and his father, Bruce Hunsucker. He leaves behind his cherished children, Julie Howerton (Darren), Louisa Hunsucker (Nicholas), and Tuekwe Hunsucker. He was a proud grandfather to Dani, Harlee, and Darren Howerton, and Mason Ferris.

He is also survived by his siblings: Benjamin Hunsucker, Antionette Hunsucker, Brandon Scott, Lewis Scott, Sonia Hunsucker, Klinton Hunsucker, Andrew Hunsucker, Andrea Hunsucker, Alyssa Hunsucker, and Peter Hunsucker, along with numerous extended family members and friends who will carry his spirit forward.

Jason’s warmth, humor, and unwavering devotion to his family and community touched the lives of many. His love and commitment to those he held dear will be remembered and cherished forever. He will be deeply missed by all who knew him.

Jason’s Wake will be held on Monday evening, November 11, 2024, at the Tulley Creek Community Center, and funeral services will be on Tuesday, November 12, 2024, at 11 a.m at the Wautec Shaker Church. Eats will follow directly after. Family and friends are welcome to celebrate his life and share in the memories that made him so deeply loved.

“Jason’s love for life and family lives on in our hearts forever.”

Pall bears are Tuekwe Hunsucker, Ben Hunsucker, Brandon Scott, Lewis Scott, Andrew Hunsucker, Sonia Hunsucker, Pergish Carlson, Cawtep Sylvia, and Charlie “Cheese” McCovey.

Honorary pall bears are Tuekwe George, Nickwich Carlson, Bobby Hunsucker, Peter Hunsucker, Klinton Hunsucker Darren Howerton, Lorenzo Manuel, Nicholas Rabah, Mark Scott, Cooper Scott, Andrew Hunsucker Jr., Poy’-we-son Hunsucker, Bodhi Scott, Jade Scott, Woodsie Hunsucker, Kilagyah Hunsucker, Benjamin “Big Guy” Hunsucker, Bronson Lewis Jr., Louie Meyers, Anthony Carlson, Ralphie Logan, Buck Logan, Virgil “Boogsie” Green, Daryl Mabry, Daniel Whitehurst, Micheal Gabriel, Rick Sanderson Sr., Lloyd Owens Jr., Vito Cosce, Louie Cosce, Axel Erickson, and Willie Lamebear.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jason Hunsucker’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Janet T. Bessette, 1931-2024

LoCO Staff / Monday, Nov. 11, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It is with great sadness that we announce the passing of our beloved mother, Janet T. Bessette, on November 1, 2024 — appropriately on All Saints Day, a day of fitting remembrance. Janet Theresa {Lemieux) Bessette was born on March 26, 1931, in Whitefield, New Hampshire, to Antonio Lemieux and Marion (Drouin) Lemieux. She grew up in Littleton, New Hampshire, where she completed her education, before moving to Pittsfield, Massachusetts, to work for General Electric.

Janet was a woman ahead of her time. As a young woman, she lived independently - renting her own apartment, buying her own clothes, and walking each morning to the corner cafe’ for a bowl of oatmeal before heading to work. She often shared fond stories of this chapter in her life with her daughter.

Janet met her future husband, Leo, babysitting for his sister and brother in law . The four of them became very close friends and soon after, she became very much a part of his family. Janet dearly loved her sister laws children. Janet and Leo married in July 1952 in Littleton, New Hampshire. Soon after they flew to California when Leo was called to serve in the Korean War. Janet stayed on in California and worked on the Naval Ordinance Test Station base in China Lake, until his return.

Upon their attempted return to the East Coast, they decided to drive up the West Coast to visit our Uncle and Aunt who lived in Eureka, our dad’s brother and his wife. Mom had severe “car sickness” that didn’t seem to go away. Our dad mentioned this to his brother with great concern and our Uncle John, advised our dad that mom might be pregnant! This story got a lot of big laughs throughout our lives, because it had never even crossed their minds. They ended up spending the rest of their lives here in Humboldt County. They went on to have 6 children in all.

Janet was a dedicated wife, mother, Memei (grandmother) and volunteer. While raising her five children with her husband she worked multiple jobs, including a long tenure as a bookkeeper for a local title company. She was a dedicated volunteer to St. Joseph Hospital as well. She devoted 50 years of service, where she became the longest-serving volunteer in its history thus far. But, one of her most enjoyable job experiences, was when her dear friend, Vivian Gill, asked her to help at their little grocery store for just a couple months. Happily this endeavor lasted for 3 years and the two of them had a ball. They had remained life long best friends.

Janet is survived by her remaining four children, Tom (Nancy) Bessette, Dan (Moira) Bessette, daughter in law, Roxanne Bessette, Paul (Vicky) Bessette and daughter, Joy Bessette. She leaves behind her grandchildren that she deeply loved. Leo Bessette, Matthew Bessette, Tyler Bessette, Casey Lund, Jared Lund, Natalie Bessette and Nick Bessette. She also leaves behind many great grandchildren that she was so fortunate to enjoy.

Janet is preceded in death by her husband of 55 years, Leopold Bessette; her son, Rick Bessette; and her infant son Michael; her parents; two brothers and a sister. Also she is preceded in death by her grandsons Lucas, Michael and Anthony.

In accordance with Mom’s wishes there will be no formal funeral service. However, a Mass will be held in her memory at a later date, to be announced.

I would like to thank her many friends our mom made at The Meadows Apartments, here in Eureka, where she lived the last 10 years. They offered greatly appreciated friendships, dropped off meals, stopped by with a little wine and a cheese plate or to play some high stakes card games.

My deepest gratitude also goes to Larona Farnum and the incredible staff at Timber Ridge, where mom spent her final two months. She and her staff were exceptional and always so cheerful, reliable and accommodating. We can’t begin to thank them enough.

We are deeply grateful to Hospice of Humboldt for their compassionate care, unwavering support and kindness during moms final days, which brought comfort to both her and her daughter.

Donations may be made in her honor to Hospice of Humboldt 3327 Timber Falls Ct. Eureka, CA 95503 or www.hospiceofhumboldt.org.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Janet Bessette’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

LETTER FROM ANKARA: New City, Old Friends

James Tressler / Sunday, Nov. 10, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Letter From Ankara

The Mausoleum of Ataturk. Photo: Kee Yip, via Flickr. License: CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

The Charlie I remembered was a college boy, a partier. Later he became quite successful in the financial district of New York. The Charlie I knew was an adventurer, an avid rock climber who’d conquered many precarious peaks.

When my wife Ozge and I passed through New York in 2015 following our wedding, it was good old Charlie who left us a spare key for his rent-controlled apartment in Midtown (he attending a hot tub party in Puerto Rico, but he did manage to arrive in time for us to enjoy an evening of panatas at a nearby Argentinian restaurant). A few years later, he visited Turkiye, he texted that he wished adamantly to avoid city life as much as possible. Climbing in the Turquoise Mountains was his chief priority, but to his credit, he did manage to join us in Istanbul for an evening of drinks at the Zurich pub in Kadıköy.

And now Charlie – “that” Charlie – was in town. I was both excited and anxious. A lot had happened since the last time we’d seen each other. Along with the pandemic and other global events, Charlie had found time to get married (we’d meet her at last), given up his job and (alas!) the prized rent-controlled Midtown apartment. At present they were in the midst of a year-long trip around the world. Prior to their arrival in Ankara, they’d been in Georgia, Armenia, Azerbeijan, Cyprus and the south Turkish coast.

We had a lot to catch up on. We’d changed jobs, we’d changed cities, we’d changed circumstances. But had we changed? This is always the worry when reuniting with old friends, so I looked forward to his visit with excitement and some trepidation.

###

Roaring Friday. I jumped aboard the crowded metro, full of heavy tired scents and breaths of an expired workweek, and began to anxiously anticipate seeing Charlie. They were staying at a hotel near the Kizilay metro station in the city center. With my phone on the last of its battery, I found the hotel, just a five- minute walk from the broad, busy plaza.

At reception, I called up and was gratified to hear the sound of my old friend’s voice. “Be right down!” he said. I sat in the lobby, savoring the dark interior, the soft chair, as well as the feeling of Friday and the weekend of nostalgia and excitement that lay ahead. Charlie came down the stairs, and we embraced heartily. “Man, you look exactly the same!” he said. “So do you!” I could feel the years of rock climbing in his hug, dense solid muscle. “Thanks!” he said, grinning his old youthful USC grin. “Yeah, still at it when I have time. Got this too though.” He pointed down to his stomach, which had the beginnings of a paunch. “All the food and drink from our travels. Anyway, Deanna will be down later. Still resting from the trip. So should we grab a beer?”

“Sure. Where?”

“Dude, I’m following you!”

We stepped out into the street, walking side by side. One of Charlie’s most endearing traits is it always feels like you just saw him, even if it’s been years as it tends to be in our case. Indeed, as we walked along in search of a pub, it might have been Müstek in Prague in 2004, if not Ankara in the present day. That reunion anxiety that always weighs, the fear of disappointment, even disillusionment, evaporated in that cool autumn air.

With some embarrassment, I confessed that I wasn’t sure where a pub could be found in the vicinity. Even after a year in Ankara, I still scarcely knew my way around. We live on the Bilkent University campus, on the city’s outskirts, and my wife and I are so busy with work and with raising our son that we hardly ever venture into the city proper. Most of my drinking nowadays is confined to the balcony at our lojman on Friday nights.

“Gotcha,” Charlie said. “Well, let’s just see what’s nearby,” he tapped mobile screen. “It says there’s one this way. Bira Park.” Bira means “beer” in Turkish.

“Beer Park – sounds good!” “Yep, that’ll do!”

Bira Park was on a quiet, narrow street. The bar itself sat beneath a pleasant canopy of leaves, some still green even in the heavy autumn. The interior was calm, with only a handful of serious-looking, mustashioed Turkish men contemplating pints of Efes. Charlie and I sat at a table of four in a corner that looked out at the quiet, leafy street. “Let me get these,” Charlie insisted, rising and heading to the cash register. “Efes?” he asked, turning. “Bomonti,” I suggested, preferring its smooth, ice-cold flavor. “Two Bomontis,” my friend said. The barman brought the bottles over, and we raised a toast. “Şerefe,” Charlie said, testing his recently acquired Turkish. “Şerefe!” I said. It felt good to clink bottles, as if the order of the universe were restored.

An hour passed swiftly, joyfully. The evening air was like late summer rather than autumn, and it felt as if we were sitting in a locale on the coast rather than the plains of central Anatolia. The talk traversed time, distance. As Charlie talked, I recalled the fresh-faced youth he was when he (and his mother, something we still tease him about) arrived at the flat in Prague all those years ago. Now, he was older than I was then, when I was considered the elder statesman at 33. The cheeks were ruddier, the once-gold, handsomely parted hair was now even thinner than my own, yet the same bright smile and keen blue eyes, the same boyish energy that I recalled him displaying at all those red light district night spots we used to haunt in the Golden City … Nebe, Le Clan, Studio … the names and faces flickering in long ago wan blue light.

“You know, thinking now about the book you wrote,” Charlie said. “It really was a magical time.” So it was. That autumn I’d left my newspaper job in Eureka, just as Charlie had decided to take a break from his studies, and in the town of Rathmullan in Ireland, a then-21 year-old Martin had opted to cape the pub he was working in to try his luck in Bohemia. And somehow the three of us found ourselves in Prague, for different reasons perhaps, but united in trying to survive that first, long cold winter — mostly with the aid of the city’s famous beer and nightlife. The three of us in the mornings were a sight – spun-out vampires ghoulishly boarding the metro homebound, while Praguers set about their normal routines.

We talked about Martin, whom we’d both gone to see in Dublin, where he and his wife and son reside. We laughed, recalling how back then Martin was our ringleader, the king of Prague nightlife. How ironic it was that of all of us, he appeared now to be the most settled, with a high-paying job in the tech sector, a fine house in the suburbs and a healthy routine that even included waking up early and lifting weights.

In our Prague days, Martin had been the hub, the star, Charlie and I his brilliant satellites, I the elder one and Charlie the college boy rookie. When Martin left Prague, Charlie and I had been at a loss. On our own we didn’t know what to do, and it was in that state that Charlie sadly (but sensibly) decided it was time for he too to go home and complete his studies at USC, which he did, and moving to New York after graduation. That left me on my own in Prague, where I stayed a few more years before moving on to Istanbul, where I met my wife.

###

“Who’da thought?” we enjoined, shaking our heads in mutual disbelief. Most of these things were just subtext as we sat there in the bar, lifting our bottles, our faces glowing with the memories. Who’da thought that 20 years later we’d still be in touch? That we’d all be so “responsible?” That Charlie and I would have established our own fine friendship? That we’d be sitting here, right now in Ankara having drinks and reminiscing? Even Martin, third member of the original triumvirate, seemed to be there in spirit (in fact, we later texted him and he responded warmly).

We kept in touch on social media, so we already had some idea of what the everyone had been up to. Charlie wanted to meet my little boy, and I was curious to meet Mrs. Charlie. Now, as the second bottles gave way eagerly to their reinforcements, we filled each other in on the details. Charlie was interested in hearing about my job teaching at the university, the benefits such as discounts for our son at the school, the mundane but “fun” aspects of raising a kid. “So is Leo bilingual?” Yes, I was proud to report. “Lucky boy!”

I already knew that Charlie and his new bride had quit their Manhattan jobs, as well as the city itself. From what I gathered, Deanna was a bit of a hippy at heart, like her husband. The two had bought a van and lived in it for a year, traveling around the country and happily (“Well, it can be a lot of work!”) roughing it. Charlie, who’d had a thing for Puerto Rico ever since his hot tub party days, introduced Deanna to the charms of that Caribbean island. Eventually the two of them invested in property, buying, renovating and renting apartments on AirBNB.

“It has been rough here and there,” Charlie explained. “I mean, the first place … we were living in the place while we were renovating it. So during rain storms we’d have all these buckets all over the place, and during the night we’d have to get up from our sleeping bags and empty the buckets, move them around to catch fresh leaks!”

A manager is looking after their properties while they are away on their magical mystery tour.

“By the way, where are you headed after here?” I asked.

“Istanbul for a few days. By the way, you’ll have to give us some recs!”

“And then?”

“Then? India. For six months.”

“Six months!” I exclaimed, my wonder mixed with a trace of envy. “Really?”

“You know Goa?” I’d heard of it, a resort popular with Brits. “Yeah, we’re going for the yoga, meditation, techno dance parties …” I confessed my travel envy. With a contract-bound teaching job, a kid in school and other responsibilities, I felt wistful of the days when one could zip off to another continent at a whim’s notice.

“Well, yeah,” Charlie said, nodding. “But truth be told, we’ve basically been homeless for a while now, all this traveling around. We do miss it sometimes, having a place to call home.”

“So I guess we both feel a like something is missing …”

“Hey, the grass is always greener, eh? Şerefe!”

“Always.”

About the time we were arriving at this existential truth, a bright voice shouting “Hey!” came all but sailing into the bar. Deanna arrived, bringing the arrival of dark with her. She looked a bit like Charlie, with her gold complexion, bright smile and outdoor energy. We greeted each other as old friends (“I’ve heard so much about you!” “Yeah, I feel like I know you already!”). By then, Charlie and I had already covered most of the years, people and places, but as the garson, obviously charmed by the lady’s arrival, brought more beer and as Deanna took off her coat and sat down, we filled her in. Clearly, she had already heard many of these tales, but didn’t mind hearing them again.

We arrived at the present, and Ankara. We talked of my wife, who I wished were there. She was at the family house with Leo, tired from a long day at work. We talked of how Charlie and Deanna had met. We talked about life in Puerto Rico and life in Turkiye, of the ups and downs of being a foreigner in general. You felt as though you could sit forever in that cozy bar, with the quiet night street outside and the autumn leaves drifting along the pavement, with the past and present flowing with the Bomonti.

We talked about why they had left New York.

“I was working 60-hour-plus weeks,” Charlie recalled, his wife listening and looking to me in agreement. “And I mean, I was earning a ton of money and yet I didn’t have anything to show for it! I couldn’t afford to buy an apartment, for example.” Deanna worked as a physical therapist, and also earned good money.

We talked about why we’d left Istanbul: the February 2023 earthquake in Turkiye, which had devastated the interior of the country, leaving 50,000 people dead. While we in Istanbul were not directly affected, it was the last straw for my wife. We’d settled in Ankara because it is reported to be the safest area of the country, seismically speaking. But it was more than that, in hindsight.

After more than a decade working at the national palace, commuting each day on the over-packed metro or squeezed onto a minibus, my wife decided she’d had enough of the Great City.

“Hey, I was done with New York, to be honest,” Charlie concluded, listening.

“So you don’t think you’ll move back?”

“No,” they both said.

We had that hazy glow that comes with the alcohol and nostalgia and soft light coming from the street lights and dim lamps in the bar. Absorbing all the stories, the years, our diverging paths, I felt I were sitting at the table in “My Dinner With Andre,” only replacing the name with Charlie.

I told my friends about how we sold our first apartment in Istanbul, how wife had used that money to leverage the purchase of a bigger apartment in the city not far from the Ataturk Memorial, and boasted somewhat about my wife’s keen real estate acumen. My wife. She was like an invisible fourth guest at the moment, probably at the moment giving Leo his supper. Talking with her mother about what they could prepare for the special vegetarian dinner we were planning to serve my guests when they visited the following evening.

“Speaking of food,” said Deanna. “Should we go and get something?”

“Absolutely!” said Charlie. They were both starved after the long train ride from the south coast. Now as we rose, they insisted on paying the bar tab, not just as old friends but also a sympathetic nod to inflation and the dollar-lira exchange rate.

Out in the streets, Friday night was starting to pick up along the broad plaza that is Kizilay. Department stores and shops were all brightly lit, and cars zoomed past tiredly and gayly. People crossed the busy streets in search of restaurants and cafes and bars. As we crossed, with me leading the way to a back street I had seen once or twice and that was thronged with a multitude of eateries (there had to be at least one place that served vegetarian, I reasoned aloud), I reflected how little time I’d taken to really get to know Ankara. I confessed as much to my visiting friends, who laughed.

“No worries!” Deanna said, with that bright, easygoing way she shared with her husband. “After all, sometimes it’s nice to see things together, with a new set of eyes, right?”

Right the lady was. As a matter of fact, we did manage to find a restaurant that served a veritable feast, Turkish style, with the staff showing all the classic hospitality, bringing one plate after another, to the amazement of my guests. (“It’s a feast!” “The way they keep bringing you more and more food – oh!”) We left an hour later, stuffed and with a surprisingly reasonable bill. “I’ll definitely have to bring Ozge and Leo here,” I said, making a mental note of the place.

###

The following day got off to a much slower start. I slept at the lojman in order to check on the cat. When I awoke, tired and slightly hungover, I figured I’d give my guests a few hours to themselves. Around lunchtime, Charlie messaged. They’d had a nice meal at the same restaurant we’d been the night before. We agreed to meet in the late afternoon near the Ataturk Memorial.

My friends were impressed by the memorial, with its stately design atop a hill surrounded by groves of trees, the leaves all turning red, brown and gold. The golden hour arrived just in time for us to pose for pictures. A taxi later took us to the old city, where we hiked up a winding, cobbled road past rows of medieval shops (battle axes and crescent-shaped cleavers were on sale alongside the rugs and coffee pots) to the site of Ankara castle. At sunset, we had a panoramic view of the city, the skyscrapers and monuments and stadiums; its 6 million residents all out there in the fading light, and the vast distances and hills beyond the city.

It was time for the dinner. We arrived at the townhouse, just a few blocks from the Ataturk memorial. In the kitchen my wife’s mother and sister, both looking a little tired, said everything was ready: a homemade Turkish dinner – vegetarian. My friends were already well aware of Turkiye’s famous meat culture, so they could appreciate the effort that had been made on their behalf. They showed this appreciation with warm handshakes and smiles, which my family welcomed and returned in the typical Turkish style. They were off to spend the evening with relatives in the city, leaving my wife and I to handle the rest of the evening.

So we had the place to ourselves. As Charlie and Deanna made themselves comfortable in the living room, my son Leo, surprised and delighted to hear English being spoken, played hide and seek and engaged in a run-and-slide game of his own invention, while my friends smiled and introduced themselves.

As you might expect, the dinner was something of a masterpiece, with smoked eggplant, bulgar, beans, a special traditional soup, the flat bread called gözleme, as well as homemade yogurt that is ever present, an assortment of salads and fresh fruits, and a dessert of chilled pumpkin and walnuts served with tahin, the peanut-tasting syrup. Again, my friends were in rapture, both at the savoriness of the dishes, but also by their sheer number of variety.

We went through several bottles of wine, and I was happy to see everyone at the table, my wife catching up with Charlie and getting acquainted with Deanna, while Leo sat on the sofa watching episodes of “Sesame Street.” In our bright, warm little townhouse, with the dark autumn night outside, it felt good to be in Ankara, in the company of family and friends.

“James hates Ankara,” my wife had said earlier, reminding me of things I’d said over the past year. “He never wanted to leave Istanbul!”

Yes, I had said those things, and many more. But now things felt different, both new and familiar – like being among old friends who you haven’t seen in a long time.

“Maybe I’m getting used to it,” I said.

A little later, the wine gone and sleepiness creeping in on our reminiscing, my friends rose to leave. They had to pack for an early train to Istanbul in the morning. With hearty hugs all around, they bid us farewell and set off into the night and walk back to their hotel.

My wife and I sat out on the balcony, having cigarettes, both of us a little quiet.

“India,” we said. “Six months. Must be nice.”

“Are you jealous?”

“Not really.”

I wasn’t – not the way I would have been at one time. It was nice sitting on the balcony of our little townhouse in the city, looking out at the quiet, pleasant street. It wasn’t India, but it was home. Our home in the new city. Maybe I had my old friends to thank for helping me see things that way.

###

James Tressler, a former reporter and Lost Coast resident, is a long-time LoCo contributor. He now resides in Ankara.

PASTOR BETHANY: What Does it Mean to Be a Good Human Today?

Bethany Cseh / Sunday, Nov. 10, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Faith-y

Everyone has blind spots. There are perspectives we just can’t see. Even when we’re told and shown that they’re there, it can still be really hard to see them. We have to work at seeing what isn’t obvious to us. We have to work at believing other people when they tell us what they can see, even if it’s never been our experience.

Knowing we have blind spots keeps us humble. They invite us to ask ourselves, “What does it mean to be a good human today?” However, our blind spots can also shut down conversation if we continue forth in ignorance. Instead of the previous question, we might pad our blind spots with protective religious platitudes, keeping others at a safe and comfortable distance: “Everything happens for a reason,” “Trust God,” and the one I’ve heard many times before, “God used the womanizer, King David, and he wrote the Psalms!” What a perfect way to shut down conversation and stop hearing grief.

I guess that’s what I want to ask of us, regardless of who we voted for. Listen to the grief of those closest to the pain and fear. Really listen. Don’t gaslight their grief. Don’t receive their grief, wrap it with some positive bow, and hand it back shiny with that silver lining you graciously added. And please don’t say,“It’s not all Christians,” like that’s supposed to make those grieving feel better. That phrase isn’t helpful. We all know “It’s not all Christians / Muslims / liberals / conservatives / straight / queer / white / BIPOC / disabled/ ambulatory…” who do this or that or think this way or that way. Deflecting blame sure keeps us inactive and comfortable, and it’s a damn privilege to feel comfortable.

A president won’t save us. They won’t fix everything or make everything comfortable for everyone, even though half of us seem to get hoodwinked every four years. We can only save each other. And the more we surround ourselves with those who think, look, vote and behave like us, those are who we keep saving. And this cycle can continue for me, insulated with pale skin and straight teeth revealing pedigree like currency—protected and encased, with the benefits of comfortable privilege.

It takes effort to unzip and step out of this encased space. It takes effort to listen to those closest to the grief. It takes intentionality to recognize our blind spots every day. When I think about Jesus, he could have lived a comfortable life surrounded by popular religious and powerful thinkers who interpreted Torah with pomp and circumstance, protected and revered. But he lived on the fringe, surrounding himself with outcasts and hurting people often overlooked by the powerful. He said those who are grieving are blessed, because God is closest to them. Those who are poor, who are merciful, who make peace, are blessed. Jesus listened to the hurt and was near to those in pain without saying God’s ways were higher than their ways. He was present, and I hope I can be present too. Because I cannot see my own blind spots without you telling me what you see.

What’s done is done, but it’s never really done, is it? Tuesday doesn’t define today or tomorrow and every day after Tuesday is more important with how we behave and live, love and give ourselves for that common good. You might be cheering. You might be grieving. You might feel paralyzed and question everything you ever believed in. Be kind to yourself and others. Drink enough water. Pet your cat. Text a funny GIF. Do five push-ups. Pray The Lord’s Prayer at breakfast, lunch and dinner. Send a card to some kids at The Raven Project. Because the hope of tomorrow is greater than the grief and fears of today.

Obama wasn’t our savior. Reagan wasn’t our savior. Harris wouldn’t have been our savior. And Trump won’t be our savior. To place one’s faith in a politician is an endless folly you’d think we’d have learned from by now.

Really, though, I am not without hope. I am not under the covers in despair because my faith is in Jesus, and in you. I believe in goodness, and even though the people have spoken I believe we will still show up with a casserole for our sick neighbor and a cup of coffee for the old guy in the red MAGA hat and a hug for the trans kid, because “In the end, ‘politics’ means ‘how I treat my neighbor.’”

The work of LOVE continues forth, regardless of who is in the Oval. May we see what you see and may we humbly keep our eyes open.

###

Bethany Cseh is a pastor at Arcata United Methodist Church and Catalyst Church.

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Election Recap — It Wasn’t All Bad!

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, Nov. 9, 2024 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Image: Stable Diffusion.

Elections have consequences. What does four more years of Trump mean for our environment? (Hint: It’s baaaaaaaaaad.) But local elections were a lot better.

In Eureka: Measure F failed spectacularly, firmly clarifying that Eureka voters want more housing and approve of the city’s parking lots-to-apartments plan. The rejection of Measure F also hints that while money matters in politics, it only can get you so far. City Councilmembers Scott Bauer and Kati Moulton were re-elected too, which the EcoNews sees as an endorsement of the direction of the city and a rejection of the Take Back Eureka crowd (again).

In Arcata: Incumbents Stacy Atkins-Salazar, Sarah Schaefer and Alex Stillman appear to have won. (Political newcomer Genevieve Serna may still be within striking distance of Stillman.) What unites these candidates? All four of the top vote getters are firmly pro-housing and were supportive of the Gateway Area Plan. Two of the candidates most critical of Arcata’s housing ambitions failed to eclipse 8% of the vote. The EcoNews sees this as an endorsement of the pro-housing direction of the current council.

Zooming out to the state: Voters appear to have approved Proposition 4, the California climate bond, which will invest $10 billion into fighting the climate crisis. This money may be particularly important given likely disinvestment in climate action from a unified Republican Congress and White House.

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: Three Generations of Freshwater’s Pioneering Coeur Family — Grocers, Athletes and Soldiers

Jeremiah R. Scott Jr. / Saturday, Nov. 9, 2024 @ 7:30 a.m. / History

The old Freshwater Store. Photos courtesy Gerald Coeur, via the Humboldt Historian.

The Alexander Coeur family first came to Humboldt in the 1880s, and started the Freshwater Store in 1894. Harold Coeur, a second-generation son, served in World War I, and third-generation son Gerald served in World War II. All three generations operated the Freshwater Store, from 1894 to 1967. This is a history of the Coeur family, their military service, and their service to the community through the Freshwater Store.

Born in France in 1854, Alexander Coeur later immigrated to Nova Scotia, where he met and married Nellie Harrigan. The newly married couple arrived in Humboldt County in 1880. Alexander Coeur obtained work as a mule train skinner and a horsewagon deliveryman with the Alexander Brizard Company, transporting domestic goods and merchandise from A. Brizard store headquarters in Arcata to the various Brizard stores located to the east in the gold and silver mining communities.

The Alexander Coeur family. Back row, from left: Nellie and Alexander Coeur and daughter Marie. Front row, from left: Ernest, Lena, and Harold (Gerald Coeur’s father). 1908.

The Brizard Company then appointed Alexander Coeur as Brizard store manager at New River (Old Denny) in Trinity County, where Coeur also became postmaster. From 1883 to 1896, Alexander Coeur was general manager at three separate Brizard stores located on the New River: at Francis; at Coeur (named for Alexander Coeur); and White Rock. By the 1890s, Alexander Coeur was ready to go into business for himself, and in 1894 he and Nellie Coeur purchased the Freshwater Store from the McGeorge Family. (Daughter Miss Edith McGeorge was an English teacher and vice principal at Eureka High School for thirty-plus years until 1936.)

The Freshwater Store was located at present day Freshwater, seven miles east of Eureka on the Kneeland/Freshwater Road with Freshwater Creek nearby. The Freshwater Store served a large area surrounded by Excelsior Lumber Company and Pacific Lumber Company timberlands. Travel to the Coeur Freshwater store was by train, mule, and horse and wagon.

According to an 1892 memoir by Hazel Mullin (spouse of Earl Mullin) on file at the Humboldt County Historical Society, the community of Freshwater had seven saloons during these years. She writes: “The white building next door was another saloon; there were seven in town.”

Alexander and Nellie Coeur had four children: daughter Marie (Lambert); son Harold; daughter Lena (Bowers); and son Ernest.

Harold Coeur, born in 1895, served in the U. S. Army during WWI, from 1917-1918, guarding for the allies the port of Vladivostok, an open seaport in Siberia, Russia on the Sea of Japan.

Upon his military discharge in 1919, Harold returned to Humboldt County and married Helen French of Eureka. Helen’s father, William (Bill) French, was a City of Eureka police officer, serving as traffic officer in the 1920s and 30s.

Harold and Helen Coeur took over the operation of Freshwater Store in 1920. Alexander Coeur died the following year.

Harold and Helen French Coeur had two children: Gerald A. Coeur and Virginia Coeur. Daughter Virginia married Francis Cook of Petrolia and settled on the Cook Ranch, where she raised three sons.

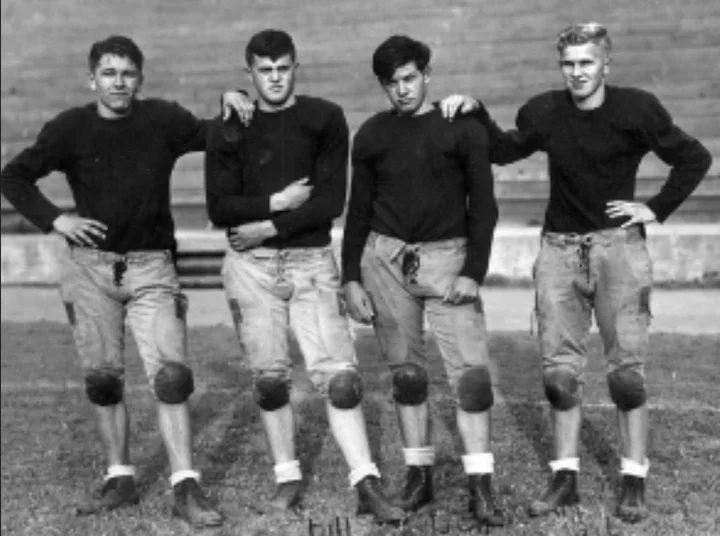

Gerald “Gerry” Coeur, born 1921, attended Garfield Grammar School in Freshwater, and then graduated from Eureka High School in 1940. As a Eureka High Logger Gerry lettered in four sports: football, basketball, baseball and track. In track he was Humboldt County track meet champion in 1939 and ‘40 in the one-quarter-mile run and second in the one- half-mile run. In football, as a sophomore halfback in 1937, he was a reserve behind the great Don Durdan and Len Longholm as the Loggers won the Northern California Championship by defeating San Jose 14-7. He was starting halfback in fall ‘38 and ‘39. In basketball, Gerry was a starting guard for two years. In baseball, he was a pitcher and outfielder for coach Les Mooneyham.

Eureka High football players, 1939. From Left: Gerald Coeur, HB; Bill Prentice, FB; Bill Ingram, HB; Gilbert Matsen, QB.

Gerry entered Humboldt State College in the fall of 1940 as a communications major. His academic goal was to become a radio announcer. In his sophomore year at HSC the events at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 drew America into World War II. In January 1942, Gerry hitchhiked to San Francisco with the intent to become a pilot in the Army Air Corps. At the Ferry Building on Market Street, however, the Army line was long. While waiting in the Army line, Gerry noticed a shorter line with a large sign “Fly Navy.”

Soon he was in the Navy line, then he was taking physical and mental tests. He passed and was advised: “We will contact you.” He returned to Humboldt and in February 1942 the contact came. Gerry traveled by railroad and bus to Bishop, California for the first of several flight-training programs. He completed ground school with mechanics of flying and transferred to the preflight course at St. Mary’s Moraga Campus for three months (no flying).

At Livermore he underwent eighty hours of primary flight training in a two-seat open cockpit Boeing Stearman. His flight instructor was Lt. James Cady of Humboldt County. Cady’s father had been tender of the Trinidad Lighthouse. Cady was an athlete at HSC and later coached and taught at Arcata High School.

Gerry was sent to Cuddihy Field at Corpus Christi, Texas, for flight school, including night flying and formation flying. At Kingsville, Texas he received advanced training in shooting flying targets, dive- bombing, and navigation. He was commissioned an Ensign U. S. Naval Aviator and was assigned to OpaLocka, Florida Naval Station for Navy fleet training in a Brewster Buffalo. Considerable time was spent on field carrier landings. From Opa-Locka he was sent to Chicago to make his first carrier landings on Lake Michigan. The Navy had two converted ferries, the Sable and the Wolverine. All Navy pilots headed for sea duty would make six carrier landings on one of these vessels.

Gerald Coeur, second from left, with other members of the Sundowners squadron, circa 1943.

After a short leave home to Freshwater,

Gerry was assigned to San Diego Naval Air Station. In

July 1943 he volunteered to go to Alameda to join the

VF II “Sundowners” Fighter Squadron that had just

returned from the Guadalcanal Campaign. Here he

flew the newest and hottest Navy fighter — the Grumman Hellcat. The Grumman Hellcat had six 50-caliber

machine guns in the wings, eight five-inch rockets under the wings, and could carry up to a one-thousand-

pound bomb.

In Alameda, Gerry was close enough to fly home on his days off. “We had a good skipper,” recalls Gerry, “and we could take a plane on a 300-mile radius. At that time our local airport in McKinleyville was a small naval air station under Alameda command, so I could fly home.” On his way to the McKinleyville airfield, Gerry would announce his arrival as he flew over Freshwater by doing a loop and a roll over his hometown. “If the Navy had seen that,” recalls Gerry, “I would have been grounded and put on the end of a paintbrush!”

Gerry’s fighter squadron consisted of forty-five pilots and was joined by thirty-five dive-bomber pilots and thirty torpedo-bombing pilots. The three squadrons shipped to Hawaii and met the newly constructed aircraft carrier USS Hornet (CV-12) at Hollandia, New Guinea. Their ship had been named in honor of the previous Hornet (CV-8), which had been sunk at the Battle of Guadalcanal in the fall of 1942.

The Hornet moved to the Philippine Islands invasion supporting General Douglas MacArthur. Gerry’s fighter pilot squadron supported the invasions of Okinawa, Leyte Gulf, Manila Bay, Luzon, Lingayen Gulf, and Mindanao. They also flew strikes into mainland China and Indo-China.

As a pilot of the Grumman Hellcat, Gerry Coeur recalls that the Grumman plane had better armament and pilot protection than the Japanese Zero, made by Mitsubishi, when engaged in combat. He successfully shot down several Japanese Zeros and supported US ground troops on island invasions.

In January 1945 the USS Hornet, under the command of the third fleet commander, Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, moved to the South China Sea looking for Japanese shipping and hiding along the Indo-China coast. Gerry recalls that he and his air group sank five Japanese oil tankers, one destroyer, and one destroyer escort near Cam Ranh Bay on the Indo-China coast. Gerry Coeur, as a Lieutenant Junior Grade, was discharged from the Navy in December 1945.

Following the war, Gerry returned to Humboldt State College, where he graduated in 1948 with a degree in communications. From 1948-1952 he was a radio announcer and newscaster at KIEM radio, Sixth and E Streets, Eureka.

The Freshwater Store and Coeur family residence, circa 1924.

Then in 1952, Gerry became the third generation Coeur to own and operate the Freshwater Store. Of course, as the son of a family grocer, he had worked in the store before, but not with great success. As Gerry recalls:

When I was high school age I used to work for my Dad some. I was a delivery boy. My dad had a pickup for delivering groceries to ranches around Freshwater. Well, I had trouble with those pickups. I wrecked one, then another one. I was demoted to stocking the shelves. My dad took a pretty dim view of the whole thing.

But those problems were behind him, and Gerry successfully ran the store until 1967, when he sold the Freshwater Store. The longtime Coeur family institution had finally come to an end. The store building, now closed, still stands next to the Garfield School on Freshwater Road.

Gerry became a licensed stockbroker in Eureka in 1965, and retired from Lehman Brothers in 1988. Gerry and wife Dorothy (Rezzonico) had three children: Connie Lee; Jeff; and Marsha Coeur. Dottie died in 1988 after a successful career at College of the Redwoods. Gerry and his second wife, Georgann (Lenz), now live adjacent to the Baywood Golf Course at Bayside, where they enjoy community activities and playing golf.

The Coeur family operated the Freshwater Store for seventy-three years — a small enterprise, but in longevity second only to the famous A. Brizard Company as a “family grocer.” Through the Coeurs’ three-generation service as storekeepers, athletes, and soldiers, they have left a legacy. The Coeur family has earned our salute.

###

Ed. note from 2024: A year after this article was published, Gerry Coeur died at age 93. The Freshwater Store building is still there. It looks to be in pretty nice shape.

###

The story above is from the Spring 2014 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.