California Families Battling Addiction Fight for Their Lives After Insurance Denials

Jocelyn Wiener / Monday, Oct. 28, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

A memorial for Ryan Matlock, Christine Dougherty’s son, at her home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Christine Dougherty heard the panic in her son’s voice.

“Mom, they’re going to release me soon,” Ryan Matlock told his mother over the phone from his addiction treatment center. She remembered him sounding like he was crying. “I’m not strong enough to do this. I need help.”

At 23 years old, Matlock had already overdosed at least once on fentanyl. In this quiet Southern California community dotted with soccer fields and American flags, little blue pills laced with the highly addictive drug were easy enough to obtain.

Desperate to save himself, Matlock had begged his health insurance plan to place him in a Palm Desert residential treatment facility that knew how to handle fentanyl addiction.

But three days after he arrived at Pacifica Recovery, Matlock’s counselor relayed devastating news. Over the entreaties of his doctor and mother, a psychiatrist reviewing his case on behalf of his health plan had decided Matlock didn’t need to stay there any longer, health records show.

No one at Optum ever spoke with Matlock himself, his mother said.

On the evening of Saturday March 20, 2021, Matlock’s older sister, Haley, said she picked him up and drove him home.

That Tuesday morning, she knocked on his bedroom door.

By the time paramedics arrived 14 minutes later, the 911 operator had already instructed Haley to stop doing chest compressions.

How big is the problem?

Did a health plan’s refusal to authorize further treatment help cause Ryan Matlock’s death?

That question is at the heart of a wrongful death lawsuit brought by Matlock’s mother against U.S. Behavioral Health Plan of California, which does business with the public as OptumHealth Behavioral Solutions of California. Dougherty alleges her health plan disregarded her son’s safety; representatives of the plan insist it always adheres to clinical guidelines and follows the law.

California passed landmark mental health coverage legislation in 2020, requiring plans to provide their enrollees with all medically necessary mental health and addiction treatment. But to people enduring the darkest moments of their lives, the separation between what that law requires and what health plans provide often feels like a gaping chasm. In recent years, a variety of potential fixes that would require more accountability from plans have come before state lawmakers; most have failed.

In the meantime, the system for appealing mental health denials effectively remains broken, a CalMatters investigation found:

- Research shows most people who receive treatment authorization denials don’t appeal to their health plans; advocates say the fraction who do so often end up being denied yet again by reviewers who are not formally trained in using the decisionmaking criteria required under state law.

- Generally speaking, a few doctors, working on behalf of health plans, appear to deny almost every appeal for behavioral health treatment they review, according to data from one medical billing company about treatment facilities around the country.

- Regulators don’t have data to track these reviewers’ decisions. Neither the state’s Department of Managed Health Care nor the California Department of Insurance is authorized by state statute to routinely require health plans and health insurers to submit information about how often they deny treatment, nor do they have access to the records of the individual doctors making these denials.

- When state regulators do get involved, they overwhelmingly side with patients. For 2023 and the first eight months of 2024, for appeals related to residential treatment denials, the Department of Managed Health Care overturned health plans’ medical necessity decisions a stunning 76% of the time.

Mary Watanabe, the department’s director, called such high overturn rates “concerning.”

“I think it’s an indication that it warrants further research and looking into it,” she said.

Health plan representatives push back against allegations that they are unfairly denying mental health and addiction treatment.

Mary Ellen Grant, spokesperson for the California Association of Health Plans, said in an email that plans “strictly adhere” to the new state mental health parity law.

“Oftentimes claims that are ‘denied’ by a health plan are due to paperwork errors and often patients get the care they need with no financial impact,” she wrote. “Claims can be returned for a number of reasons that ultimately have no impact on a patient’s care or require the patient to pay for a health care service.”

More than 50 patients, family members, clinicians, attorneys and advocates described a different reality to CalMatters.

Several clinicians said they sometimes have to tell patients who they worry are at risk of self-harm that their health plans won’t pay for further treatment. That leaves providers navigating fraught legal and ethical terrain: Staying in a hospital or treatment facility after an insurance denial could burden patients with thousands of dollars of medical debt; leaving could kill them.

“That’s the hardest part, to say to someone ‘Do you want to risk it? How much are you thinking you might kill yourself?” said Dr. Alexis Seegan, inpatient medical director at the UC Irvine Medical Center and immediate past chairperson of the government affairs committee of the California State Association of Psychiatrists.

“What if they end their lives or really hurt themselves? It’s an easy risk for an insurance company, but these are real people. That’s a huge risk for them and their families to take.”

Ryan Matlock’s mother, Christine Dougherty, a first grade teacher in Yucaipa, said she’s paid her insurance bill on time every month for decades so that her health plan will take care of her family.

She said she’s suing Optum — which handles behavioral health services for United Health — because “I don’t feel they did.”

Christine Dougherty, Ryan Matlock’s mother, at her home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Dougherty’s lawsuit, which was filed in May 2022 in San Bernardino County Superior Court, alleges that OptumHealth said Matlock could safely leave the residential facility, against Matlock’s treating doctors’ assessments, “solely to save money and in total disregard of Ryan’s health and safety.”

The health plan has responded that the case belongs in arbitration; an appeals court agreed, and the case is currently set for arbitration next year.

Attorneys from Gibson, Dunn & Crutcher LLP, the firm representing the health plan, did not respond to repeated calls and emails about the case.

OptumHealth declined to answer any questions about the case or its appeals process for what a spokesperson described as “privacy and legal reasons,” although Matlock’s family was prepared to waive privacy protections. The company released a brief statement saying the health plan’s “coverage determinations are made in accordance with the terms of the member’s health plan and federal and state laws, as well as using evidence-based clinical guidelines and peer-to-peer reviews.”

Matlock’s claim file — the collection of internal records that insurance companies keep about their decisions to reject or deny claims — was provided to CalMatters by Dougherty’s attorney, Travis Corby.

Those records show that the fact that Matlock had previously been in another facility and had relapsed was one of several factors in the reviewer’s decision to deny.

Dougherty remembers screaming and crying over the phone with her health plan, begging them to let her son stay in treatment longer.

“He wasn’t a person,” she said. “He was just a number.”

Who defines what is medically necessary?

As they seek to balance competing priorities, health plans must answer a key question: Is treatment medically necessary?

California’s 2020 mental health coverage law, known as parity, requires that state-regulated plans make such “medical necessity” determinations using specific criteria outlined by nonprofit organizations that specialize in behavioral health. If the criteria indicates that a treatment is medically necessary, the health plan or insurer is then required to cover it. The concept of “parity” refers to requiring health insurers to provide equivalent treatment for mental and physical health conditions.

No one argues that health plans should never bump patients to a lower level of care. Residential facilities can cost as much as thousands of dollars a day — and not everyone needs to be in 24-hour care. Those sizable sums have also at times made the residential care industry ripe for fraud and abuse.

In Matlock’s case, criteria to determine medical necessity was laid out under the nonprofit American Society of Addiction Medicine. Since passing the parity law in 2020, the state has required plans to use this criteria to identify what kind of treatment a patient needs. It guides reviewers in evaluating everything from withdrawal symptoms to likelihood of relapse to support at home.

Similar medical necessity criteria exist for eating disorders and other serious mental illnesses.

Patients who are denied treatment authorization generally can first appeal to their health plans; this can involve a review of available records as well as a peer-to-peer review that includes a phone conversation between the patient’s clinician and a reviewer working on behalf of the health plan.

But patient advocates and treating physicians say that health plan reviewers don’t always have adequate training in how to use the nonprofit criteria, nor do they spend enough time to fairly evaluate cases.

In the absence of comprehensive public data, information provided to CalMatters by one medical billing company provides a valuable, if limited, window into an industry that can often feel like a black box to consumers.

The billing company — which asked not to be named — shared four years of data capturing more than 2,000 appeals by patients requesting mental health treatment around the country.

Per the data, health plan reviewers working with various companies denied the majority of those appeals. But that overall rate masks some acute disparities. While certain reviewers approved the majority of patient appeals they received, others said “no” to every single case they reviewed.

Of 40 identifiable doctors in the data set who conducted the most reviews, CalMatters identified 10 doctors who denied more than 70% of patient appeals; of those, four refused to pay for treatment more than 90% of the time.

Corey Waller, editor-in-chief of the fourth edition of The ASAM Criteria, says health plan reviewers ideally should have a minimum of 16 hours of training in using the criteria. Currently, he says, there’s a disconnect between how reviewers interpret the criteria, “and the reality of what it means to apply it to a real person.” He also says some of the responsibility for bad decisions lies with treatment providers, who often don’t provide health plans with enough documentation to make it easy to make the right decision.

In theory, he says, ASAM criteria could offer the two sides “a common language” to reach a conclusion about medical necessity. In practice, he said, “I think it’s really fuzzy.”

“Right now it’s causing huge amounts of risk for patients who don’t get access to care, risk of overdose, risk of relapse, families falling apart, people losing their jobs. Like, just get them into care, man, we’ll figure it out later,” he said.

Grant, the spokesperson for the California Association of Health Plans, said in an emailed statement that it is impossible to ensure a perfect match in terms of experience for the medical experts reviewing each case on behalf of the plans.

“If an exact peer match was required, the workforce shortfalls alone would create major delays in the appeals process,” she said.

Ryan Matlock’s search for help

Nestled in the foothills of the San Bernardino Mountains, Yucaipa is a sleepy bedroom community less than an hour’s drive from Riverside’s suburban sprawl to the west, Palm Springs’ tourist resorts to the east and the designer cabins abutting sparkling Lake Arrowhead to the north.

Christine Dougherty lives here with her daughter, Haley, in a 2-story home where they moved after Ryan died. In the front room, she displays a set of meticulously organized scrapbooks full of photos of her children’s birthday parties, Halloween costumes and soccer games, their frequent road trips to Disneyland and the beach.

Ryan and Haley’s father separated from Dougherty when Ryan was in middle school. After that, the children lived full-time with their mother, although Christine and Haley say the family still spent a lot of time all together.

Ryan Matlock was tall and lanky, with thick brown hair, intense blue eyes and an infectious giggle, “so happy he could talk to a brick wall and make the brick wall smile,” his friend Tyler Braden remembers. Even as a little boy, Matlock hated to see anyone sad, his mother said. At the park, he always sought out children playing alone.

Haley Matlock, left, Ryan Matlock’s sister, and Christine Dougherty, Ryan’s mother, hold a photo of Ryan at their home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photos by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Christine Dougherty and Haley Matlock have tattoos made with ink containing Ryan’s ashes. They also have a set of stones made with his ashes. Photos by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Braden first met him at the beginning of third grade at Calimesa Elementary, where Dougherty taught for 29 years. Braden, brand-new to the school, felt nervous until Matlock introduced himself. The two boys became inseparable, playing Call of Duty or Halo after school, hanging out at the skate park or jumping BMX bikes on weekends.

In their teens, they began to experiment, Braden said. A bottle of vodka. A little weed. Later, someone close to Braden gave him pills to blunt pain caused by bulging discs, he said. Matlock wanted to try them. Eventually, Braden realized they were a problem for his friend, he said, and cut Matlock off.

By then, another drug had begun growing in popularity in San Bernardino County, where Yucaipa is located. Fentanyl was a cheap, synthetic opioid that illicit drug makers were increasingly cutting into other drugs — including illegal pain pills.

Fentanyl was far more addictive than heroin, “rewiring brains,” said Stuart Cullum, a detective on the county’s overdose response team. It was also far more lethal. Some kids died the first time they tried it.

According to recollections of Matlock’s mother and sister, he initially bought pain pills laced with fentanyl unwittingly. His medical records show he first used fentanyl in his late teens or early 20s; and that eventually he was smoking or snorting up to 15 pills a day.

As time went by, Christine Dougherty noticed her already slim son getting thinner. He didn’t seem quite as happy-go-lucky; he wasn’t going out with friends. Something seemed off.

Finally, he told her the truth: “Mom,” she remembered him saying, “I need help.”

Dougherty and her children were insured by UnitedHealthcare and received behavioral health benefits from its subsidiary, Optum.

Matlock’s health and insurance records and a mediation brief submitted in court by his mother show a young man struggling in his initial attempts to address his addiction:

In August 2020, Dougherty contacted her health plan and received approval to get Matlock into treatment.

Later that month, Matlock entered a residential facility in Riverside for the first time.

Convinced he could manage his addiction himself, he left after just 13 days. Five days later, he relapsed.

Later that fall, he returned to the same facility. This time he made it 30 days, followed by almost three weeks of outpatient treatment.

As soon as the program ended, he relapsed again.

He would later complain to his mother that the facility was treating him for heroin addiction, when he was actually addicted to fentanyl, according to a statement from Dougherty attached to the mediation brief.

In that statement, she described the weeks her son spent searching for a facility that specialized in fentanyl addiction and could also treat depression and other mental health issues.

Haley Matlock, left, Ryan Matlock’s sister, and Christine Dougherty, Ryan’s mother, hold a photo of Ryan at their home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Insurance records show Matlock called his health plan repeatedly, reporting a large collection of symptoms. One insurance company log, from January 2021, described a call in which Matlock complained of: “Loss of appetite, hot and cold flashes, restlessness, runny nose, cravings, insomnia, constipation, anxiety, goosebumps, joint pain, muscle pain, tremors, chills, depressed mood, irritability, mood swings, impulsivity, fatigue, heart palpitations, tension, difficulty concentrating, headaches, sensitivity to light, paranoid ideations expressing free floating fear of unknown and lack of directions. Sweats, worry and hypervigilant.”

On Feb. 26, 2021, United Health approved his request to detox in Pacifica Recovery, a six-bed facility in Palm Desert.

The health plan’s initial reviewer noted that Matlock had “spiraled out of control with substance ues (sic)” and that he was “fearful of killing self if he does not get help.”

Upon his arrival, Pacifica recommended that Matlock stay at the facility for 90 days, according to the mediation brief. A doctor at the facility started him on a taper with buprenorphine to limit withdrawals. Matlock’s symptoms responded immediately.

But three days after he was admitted to Pacifica, his counselor, Marc Stern, approached Matlock with bad news: the health plan had refused further coverage.

Stern, a longtime counselor who has been sober for more than 30 years, said he saw potential in Matlock, who struck him as bright, inquisitive and kind.

Matlock seemed to intuitively know when other clients were struggling, Stern remembered — he would stop by the counselor’s office to alert him.

Despite the health plan’s decision, the counselor knew this kid wasn’t ready for the outside world.

“Fuck them,” Stern recalls saying. “He’s staying here.”

Insurance appeals and denials

Ryan Matlock appealed that initial denial.

Most people don’t even do that.

According to a 2023 study by KFF (formerly Kaiser Family Foundation) of people insured by Affordable Care Act plans, less than two-tenths of 1% of people who were denied treatment filed an appeal with their health plans.

In part, that’s because people don’t understand the appeals process or know their rights, said Kaye Pestaina, director of the KFF’s program on patient and consumer protections. The requisite paperwork can be difficult to complete, she said, and often requires a health provider’s assistance.

Facilities also have to be willing to invest significant time and resources to convince health plans to keep covering patients’ stays. Shawna Morris, chief executive of Casa Pacifica, said her Central Coast-based organization hired a full-time licensed clinician whose entire job is to work with insurance companies to advocate for patients to stay longer.

“A whole industry has been built around regulating and denying care and that makes me nauseous,” she said. “And then we build our own industry around fighting for and trying to get authorization for care.”

The doctor who reviewed Matlock’s case for Optum was Dr. Svetlana Libus, a psychiatrist who identified herself in the denial letter she sent Matlock as a behavioral medical director for the plan.

Dr. Libus did not respond to several emails and phone calls requesting an interview.

According to Matlock’s insurance records, the mediation brief and her denial letter, Dr. Libus decided he did not meet the criteria to remain at Pacifica for a variety of reasons. Among them: He was no longer experiencing withdrawal, he was medically stable, he wasn’t reporting unsafe thoughts, and he was participating in treatment and taking his medication as prescribed. She also noted that Matlock had already been in residential treatment, and had relapsed.

In her notes from the file, the doctor appears to have questioned his motives for seeking treatment again.

“I expressed concern that the (patient) comes to detox and relapses despite of all treatment attempts,” Dr. Libus wrote, at one point misidentifying Matlock as a woman. “This could be indicative of pt using detox for reducing amount of substances she needed to get high . (Another reviewer) shared that same concern. I also express concerns that offering pt the same interventions all over again are becoming part of the enabling system.”

She concluded that Matlock could “safely and effectively be treated” in an outpatient setting, according to the health records.

Dougherty said she begged the health plan to get on the phone with her son.

“Have you talked to him this time? Because it’s different,’” she remembers imploring them. “‘Have you talked to him about what his goals are? Have you seen the change? Have you talked to him?’”

“And they said, ‘No, we don’t need to.’”

If a patient’s request for further treatment is denied, facilities have to make a tough decision – do they keep a patient on and continue to appeal, potentially absorbing the cost if the health plan won’t pay?

Christine Dougherty, Ryan Matlock’s mother, flips through her son’s notebook in her home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

In Matlock’s case, his counselor, Stern, followed through on his promise: According to Stern’s declaration in the family’s lawsuit, Pacifica kept Matlock for two and a half more weeks while continuing to appeal to the health plan to reverse its decision. They charged only for food, Dougherty said.

During that time, Matlock seemed to his family and Stern to be making strides. For the first time in years, Dougherty noticed the light was back in her son’s blue eyes.

He started talking to them about his future, outlining the steps to get recertified as an emergency medical technician. He planned to pursue his dream of becoming a wildland firefighter.

He joined Narcotics Anonymous and met every day with a sponsor, they said. He connected with three other young men at Pacifica who made a pact to stay sober together. Stern got them all matching buttons.

In one impassioned journal entry, Matlock wrote a goodbye letter to his addiction:

“You’ve almost taken my life from me twice. I’ll be damned if I let that happen.”

Can California better regulate mental health coverage?

Could California regulators have intervened to help Matlock?

Maybe if they had known about his case.

After his health plan denied his appeal, Matlock had the right to appeal yet again: this time to the state Department of Managed Health Care.

Both the Department of Managed Health Care and the Department of Insurance allow people to request independent medical reviews, in which outside experts review cases for the state and determine whether a health plan rightfully denied treatment.

Matlock might have had a decent chance at success. According to the Department of Managed Health Care annual reports, of 186 independent medical reviews of Optum decisions during the past decade, 60% were either overturned by the state or reversed by the health plan.

But Matlock’s mother, Dougherty, said she and her son didn’t know about this level of appeal. Most people don’t.

Grant, of the California Association of Health Plans, also pointed to the fact that less than a tenth of a percent of full service health plan enrollees submit an appeal to the state.

But in her email, she interpreted the lack of appeals in a positive way:

“This is not to diminish the fact that each and every enrollee matters, but just to put into perspective that 99.99% of enrollees are getting the care they need,” she said.

Hearing her explanation, Sen. Scott Wiener, the parity law’s author and chair of the Senate Select Committee on Mental Health and Addiction, had a quick response: “I just don’t buy that.”

Advocates and some legislators have long expressed frustration that the state has not taken a more proactive role in holding health plans to account for refusing to pay for behavioral health care. Waiting for people in crisis to figure out how to navigate a complicated system is simply too passive, they say.

In California, that confusion is exacerbated by the fact that the Department of Managed Health Care and the Department of Insurance each regulates a different subset of health plans and insurers. Some aren’t regulated by the state at all, but instead are regulated by the U.S. Department of Labor.

The relatively few people who do file for independent medical reviews with the state can find themselves waiting a long time: last year, it took the Department of Managed Health Care 35 days on average to complete reviews for mental health cases related to medical necessity.

“Aggressive monitoring and oversight by the regulators should really address this troubling trend,” said Meiram Bendat, a Santa Barbara-based attorney and psychotherapist who helped author California’s 2020 mental health coverage law. “It seems to me yet again another example of lack of regulatory oversight.”

Lawmakers tried this year to legislate stricter state oversight.

State Sen. Dave Cortese, a Campbell Democrat, introduced Senate Bill 999, which would have required health plans to use mental health and addiction experts to review claims for treatment.

Sen. Wiener introduced Senate Bill 294, which would have required an automatic review when commercial health plans denied children and young people mental health treatment.

“The fact that we even have to consider that bill is an indictment of the system,” he said.

Both bills died in the Senate Appropriations Committee, with advocates and lawmakers raising concerns that the Newsom administration had intentionally inflated cost estimates in order to kill them.

Sherry Daley, a longtime lobbyist with the California Consortium of Addiction Programs and Professionals, said her organization is now looking into modeling legislation after a New Jersey law that prevents health plans from reviewing whether a patient should be allowed to stay in substance use treatment for at least 28 days after their doctor has decided they belong there. Similar laws exist in New York and Pennsylvania, she said.

Several advocates and lawmakers also said they were concerned by the lack of publicly available data about how often health insurers deny authorization for mental health treatment, including the rates of denial by individual reviewers.

Watanabe, of the Department of Managed Health Care, told CalMatters the plans aren’t required to submit that specific information to her department.

“We’re always happy to accept information from anybody who wants to share something with us for us to look into,” she said.

Remembering Ryan

The coroner’s inspector who arrived at Ryan Matlock’s bedroom on the morning of March 23, 2021 described the scene in cold detail:

Two clear plastic baggies with round light blue pills labeled M30 on the bed.

A Tilly’s credit card with white powdered residue on the dresser.

A tattoo of a rose on Matlock’s left abdomen.

A tag, number 01764, on his right big toe.

For Christine Dougherty, that day remains a nightmarish blur. She remembers the terror in her daughter’s voice on the phone that morning, speaking words Dougherty could hear but couldn’t make herself understand.

Until she and Haley moved this year, Dougherty left her son’s clothes hanging in his closet, his 27 pairs of shoes — how he loved shoes! — laid out on the floor just as he had left them.

A memorial for Ryan Matlock, Christine Dougherty’s son, at her home in Yucaipa on June 12, 2024. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

On the anniversary of Matlock’s death, she and Haley got tattoos of hearts on their wrists with his ashes inked into them. On his birthday, they and many of his friends hit up his beloved In-N-Out to order his favorite meal: a Double-Double burger with Animal-Style fries and a blue Mountain Dew.

After Matlock died, Dougherty’s attorney, Travis Corby, commissioned a review of his case from Dr. Mario Bartolome, a Roseville physician board certified in addiction medicine. Bartolome pushed back against many of the reasons Optum gave for denying Matlock coverage, including that Matlock had been in treatment in the past and relapsed.

“People who have been in treatment and failed that level of care need higher levels of service, not lower,” he wrote.

OptumHealth Behavioral Solutions of California, Dr. Bartolome wrote, “inappropriately denied continuation of coverage” to Matlock, which “significantly contributed to his ultimate death by drug overdose soon after leaving treatment.”

The year Ryan died, 317 people in San Bernardino County died of drug overdoses.

In California, that year, fentanyl alone claimed 5,961 lives. The next year, the toll climbed to 6,473. Last year, it hit 6,850.

Dougherty knows her son made the decision to buy the pills that killed him.

She also knows he wanted to live.

Data methodology

In the absence of comprehensive public data, CalMatters sought data directly from companies who work with behavioral health treatment services. A version of that data was originally shown to our reporters by Joan Borsten, the former executive director of Summit Estate Recovery Center. Data from one billing company, which asked not to be named, provides a limited window into the appeals process.

The company provided internal records of appeals to a variety of health plans for higher level behavioral health care, with the patient and site of treatment anonymized. The data comprises more than 2,000 appeals from 2021 to 2024 for patients at treatment centers across the country, including in California. Each record includes a field for the name of the doctor working for the health plan who reviewed the appeal. However, many records are incomplete and doctor names show up inconsistently. In conversation with people who work with the data at the company paired with external research, CalMatters standardized the data and was able to group most appeal cases by the doctor who reviewed the case outcome. For the 40 identifiable doctors who show up the most frequently – each with at least 10 cases with complete information – the denial rates in the dataset range from 7% to 100%. Partial approvals, such as approving 3 out of 5 requested days of additional residential treatment, are counted as approvals not denials.

###

CalMatters data reporter Erica Yee contributed to this story.

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 8 felonies, 13 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Yesterday

CHP REPORTS

V St / Sr255 (HM office): Animal Hazard

Patricks Point Dr / Shadow Ln (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

Times-Standard : Civic calendar | Blue Lake to discuss water, sewer rate increases

RHBB: Juan Heredia Assists in Ongoing Eel River Search for Missing Covelo Woman

RHBB: Cal Poly Humboldt Responds After Yesterday’s Occupation of Siemens Hall by Protestors

RHBB: California Reports Continuing Decline in Sexually Transmitted Infections

In Nationwide First, California Plans to Rev Up Sales of Electric Motorcycles

Alejandra Reyes-Velarde / Monday, Oct. 28, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

A LiveWire electric motorcycle in front of Bartels’ Harley-Davidson in Marina del Rey. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

At New Century Motorcycles in Alhambra, a handful of electric motorcycles are relegated to the back of the store, tucked behind the dirt bikes. The store sells one a month, at most, a salesperson said.

Motorcyclists have long loved their noisy, gas-powered machines that allow them to ride long distances on highways and remote roads with few fueling stops.

Now, in a nationwide first, California is planning new rules that ramp up sales of zero-emission motorcycles in its quest to clean the air and battle climate-warming gasses.

The regulations would impose a credit system for manufacturers so that 10% of motorcycles sold in California would be zero-emissions in 2028 and 50% in 2035, according to the state Air Resources Board. At the same time, a tighter standard for new gas-powered motorcycles would ratchet down their emissions for the first time in more than 25 years.

Under the proposed rules, more than 280,000 new electric or hydrogen motorcycles would be sold in California by 2045 — about eight times more than the total on its roads now. Electric motorcycles make up only 1% of current motorcycle sales.

The state Air Resources Board will vote on the proposed rules on Nov. 7 after a public hearing.

Motorcycles are more often used for recreation than for daily commutes, and they collectively emit far less pollution than gasoline-powered cars and diesel trucks. But a mile driven in a gas-powered motorcycle emits far more pollutants than a mile in a new gas-powered car — for the reactive gases that form smog, it’s a whopping 20 times more per mile, according to the air board.

In a state with the worst smog in the nation and unsafe levels of dangerous fine particles, air-quality officials say no source can be left unregulated: All vehicles powered by fossil fuels need to be cleaned up and transitioned to zero-emissions.

Several gas-powered motorcycles are parked in a motorcycle-only area in Venice. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

State officials hope more motorcyclists will be interested in the benefits that battery-powered motorcycles have to offer: low fueling costs and less maintenance.

But many motorcyclists point out California’s inadequate network of public charging stations and the limited range of electric models that are unsuitable for long-distance rides. They worry that the rule will limit the bikes they can choose in the future. Others say it could fill an untapped market for urban motorcyclists interested in fast bikes for short commutes.

“There is no infrastructure for electric vehicles,” Michael DiPiero of the American Brotherhood Aimed Towards Education of California, which represents motorcyclists, said in written comments to the air board. “We cannot support the needs we currently have for electricity as it is.”

Rob Smith, a motorcyclist from Santa Monica, owns an electric car and considers himself an environmentalist. But he’s not ready to switch to electric motorcycles — and he doesn’t think most motorcyclists are, either. They’re expensive, silent and have top ranges of about 100 miles.

“I do think it’s the future, I just don’t know about that timeline,” Smith said of the Air Resources Board’s proposal. “This is going to just hit a niche. Can you get to 50% with just that niche?”

Rob Smith, who rides a gas-powered Ducati motorcycle, said he owns an electric car but won’t buy an electric motorcycle yet because of their limited range. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Harley Davidson and the Motorcycle Industry Council, a group that represents manufacturers, didn’t respond to a request for comment about the proposed rules.

State officials said the regulation strikes a balance by moving toward electrification of motorcycles and catching up with European standards for gas-powered motorcycles yet still allowing California consumers to have a range of choices.

“We realized we couldn’t push to 100% because there will probably be some circumstances where zero-emission motorcycles won’t have access to infrastructure to plug up their bikes,” said Annette Hèbert, the air board’s deputy executive officer who oversees mobile source rules at its Southern California office.

Motorcycles make up less than half of 1% all vehicle miles traveled in California. But even though they’re a “very small part of the state’s overall transportation sector,” they contribute an “outsized portion of smog-forming pollutants,” air board officials said.

“Motorcycles (emissions) may look small when taken by themselves, but when you consider the additive effect to all those other small sources together, you can see why we’ve got to hit every little piece,” Hèbert said.

If California is to finally have healthy air as well as make progress in combating climate change, “we need to have this paradigm shift, because that’s the only way we’re going to get there,” she said.

Tons of air pollution would be eliminated

Californians breathe some of the nation’s unhealthiest air and vehicles account for the majority of that pollution. The Los Angeles basin has for decades topped the list of cities with the worst ozone, a key ingredient of smog, according to the American Lung Association. Ozone and particle pollution can trigger asthma and heart attacks, as well as other diseases.

The motorcycle regulation would lead to an estimated $649 million in savings from reduced mortality and avoided hospitalizations and illnesses associated with motorcycle emissions, according to the Air Resources Board.

By 2045, the rules are expected to eliminate about 20,000 tons of reactive gases and nitrogen oxides that form smog, and 33 tons of fine particulate matter. That would be about half of the emissions from all California motorcycles.

“I do think it’s the future, I just don’t know about that timeline. This is going to just hit a niche. Can you get to 50% with just that niche?”

— Rob Smith, motorcyclist from Santa Monica

California is proposing a tiered credit system for manufacturers. Companies that produce high speed, freeway-capable motorcycles with large battery capacities — those that typically produce the most emissions — will get the most credits. Low-speed bikes with low range will get the least.

Companies comply with the rule by producing zero-emission motorcycles for credits or trading their credits with other companies. A manufacturer, for instance, could comply with its 50% target by making and selling 25% electric motorcycles and then purchasing credits for the remaining 25% from an all-electric motorcycle company. Manufacturers would also get bonus credits for producing and selling zero-emission bikes before 2029.

Additionally, starting with 2029 models, the regulation will require new gas-powered motorcycles to follow more stringent European Union standards for exhaust emissions and use better on-board engine diagnostic equipment to detect faults in their emissions systems.

First: A LiveWire electric motorcycle. Last: The charging port of a LiveWire electric motorcycle in the showroom of Bartels’ Harley-Davidson in Marina del Rey. Photos by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Several manufacturers, including Harley Davison, Ducati and Kawasaki, already make electric bikes, and some companies, like Zero and Verge, build exclusively electric bikes. Energica, an electric bike startup, recently filed for bankruptcy due to increased costs and supply issues.

An electric motorcycle purchased in 2020 cost on average $5,365 more than a gas-powered one. State officials estimated an electric bike would save $215 annually in fuel and maintenance costs.

State officials said electric motorcycles may also appeal to low income motorcyclists who live in apartments and find charging an electric car near their residence more difficult. Less expensive electric motorcycles may be small enough to take inside apartments to charge or come with removable batteries that can be charged overnight.

But officials stressed that the regulation’s intent isn’t to convert car drivers to motorcyclists. Instead, it’s an added option for motorcyclists looking for a more cost effective mode of transportation.

Are electric motorcycles ready for prime time?

At a Harley Davidson dealer in Marina Del Rey, Live Wire brand electric motorcycles are visible as soon as customers enter the showroom. The dealer sells two or three electric Live Wire motorcycles monthly, said Justin Fraiser, a sales representative at the dealer.

“There are a lot of people in the Harley world stuck on combustion engines,” Fraiser said. But he’s not one of them. “It’s the evolution of things. Eventually, it’s gonna happen.”

Smith, the motorcyclist from Santa Monica, said he thinks electric motorcycles are the future, but they’re not quite ready for “prime time.”

Smith said California has been a leader in climate solutions “for good reason.” He said he cares about reducing emissions and protecting the environment. He is a partner in a venture capital firm that invests in startups that make electric bikes.

But he prefers his “loud and obnoxious” Ducati motorcycle for its better range (up to 200 miles) and for safety reasons — car drivers can hear him coming behind them.

Smith said the state should focus on cutting emissions from new motorcycles with internal combustion engines and was pleased to hear that was part of the regulation.

Karen Butterfield, a motorcyclist from San Diego, agreed that, for her, an electric motorcycle won’t work.

She’s a member of the Southern California Motorcycling Association, which gathers for long-distance trips, from Mexico to Canada and throughout the U.S. They ride for hundreds of miles without stopping, something that an electric one couldn’t do with existing charging network problems.

But she said there’s a massive untapped market in young riders because she thinks electric motorcycles are generally easier to use.

“I think it’s a good thing for motorcycling in the sense that a smaller electric bike would help people get into motorcycling,” she said. “The generations that are coming seem to be more environmentally conscious too, which is a good thing. I think there’s a market there, they just need to find it.”

The charging port of a LiveWire electric motorcycle in a showroom in Marina del Rey. Photo by Jules Hotz for CalMatters

Adrian Martinez, an attorney for climate advocate Earthjustice, said the organization supports the proposal, but called it conservative. The group was pushing for 100% electric motorcycles in a similar timeline.

“California has such dramatic air pollution problems that we’ve realized that we aren’t in a position to pick and choose,” Martinez said. “We basically need to get to zero emissions everywhere feasible.”

But some motorcyclists believe that mandating electric motorcycle technology isn’t necessary for a vehicle that produces relatively small emissions compared to other vehicles. People ride motorcycles as a hobby, to socialize with other motorcyclists and ride in the mountains or other remote areas.

Some people ride motorcycles as their main form of transportation, and electric motorcycles may appeal to those folks, but it’s a small percentage, said Chris Real, president of DPS Technical, a technical services company for motorcyclists.

Real said he thinks the regulation “won’t move the needle at all” in reducing emissions because most motorcyclists don’t put many miles on their bikes.

“Some consumers will adopt it, and some consumers won’t,” he said. “So very regional consumers, urban consumers that only ride you 20 or 30 miles, it won’t impact them at all. But for somebody that has to make a 100 mile commute or something, that’s not going to be viable.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

PASTOR BETHANY: Jonah, Part IV — Or, The Things You Can Find in the Dirt

Bethany Cseh / Sunday, Oct. 27, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Faith-y

Jonah and the Ninevites.

###

###

After spending three days and nights inside a watery, claustrophobic tomb, praying and crying out to the God he still believed in, Jonah was vomited out of that big fish and onto a beach. I can imagine him kissing the earth in gratitude to be alive, raising his arms up high and stretching out his sore back. Stumbling from hunger and seasickness, he looked around, hoping to find a nearby village where he could rest and reorient himself. I imagine him settling into a local inn, hearing that word from God about Nineveh once again: “Go to the great city of Nineveh and proclaim to it the message I give you.”

I wonder if he felt new excitement about his second chance at life, regardless of this old word. And as he began traveling, I bet he was full of praise and hope for those first few days. But as those days of traveling turned into a week, his excitement and fervor probably shifted, as silence and solitude can do. Silence has a way of revealing what’s actually in our hearts, but what we do with that data is up to us. He had the message, but with every silent step he took, he remembered who this message was to go to — the most horrifically violent, undeserving of mercy, people the world had ever known. I imagine him muttering and arguing with God, turning around a dozen times throughout that month of travel, his sandaled feet kicking rocks in protest.

But Jonah had a message and since he was a prophet he would bring the message to the people, because that was his job.

There’s quite a lot of ancient prophetic writings throughout the Hebrew Bible. Their messages from the Lord are long and filled with flowery language. Their prophecies contain specific details, weaving poetry, allegory, and stories together for the people. Some prophets even participated in guerrilla-type theater for dramatic affect, helping people understand the point. But it seems like Jonah spent his entire travels cutting this message down to the bare minimum, strategically sabotaging God’s words. He wondered, “How can I say what needs to be said as quickly and succinctly as possible.”

By the time Jonah arrived, he had perfected this message to five Hebrew words. He walked around the city for a few days and, like a broken record without any dramatic flair or stage presence, he announced, “In forty days Nineveh will be overthrown.”

Jonah didn’t mention God.

He didn’t mention why they would be overthrown.

He didn’t give details about what they should do to NOT get overthrown.

Or who would overthrow them.

But the king of Assyria took this brief message incredibly seriously. He stepped off his throne, away from his authority and hierarchy and power to sit in the dirt. Sitting in the dirt gives a person a whole new perspective. You can see the world differently in the dirt. You can see what matters most in the dirt. This king, covered in dirt and ash, then commanded his people and animals to do the same — to cover themselves with goat hair and stop eating or drinking anything because they were entering a time of mourning and repentance. Repentance means to stop going the direction you are heading and go a different way. It means to turn around. It reveals new perspective. For Nineveh, this story shows they ceased and stopped everything so they could discover this new direction and perspective.

This brief and vague message Jonah gave to the Ninevites was enough for them to stop everything and pay attention. And God’s response towards them was great compassion.

Jonah 3:10 : “When God saw what they did and how they turned from their evil ways, God relented and did not bring on them the destruction God had threatened.”

The word for “relented” is “nacham” which means compassion, pity, and sorrow. God saw how these leaders and people intentionally took off their robes and crowns, put on goat hair fleeces, and sat in the dust in deep mourning. God saw them with love and compassion because they were more than the harm they had caused.

God saw them.

God saw Jonah in his irritated and frustrated state. God saw the Ninevites in their desire to change. And God sees you in your uncertainty and apprehension on the decisions you must make today.

Know that you are seen with all the love and compassion. So come into the silence and be still for a moment. Step down from whatever throne you might be on and travel down to the dirt. It’s here in the dirt you might see that new perspective you need. It’s in the dirt — the same particles and atoms you’re made from — you might know you are seen and loved by Love. Mercy is near.

###

Bethany Cseh is a pastor at Arcata United Methodist Church and Catalyst Church. Follow her on Instagram.

Humboldt Transit Authority Secures $18.7M Grant to Fund the Region’s First 15-Minute Intercity Express Line

Isabella Vanderheiden / Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024 @ 12:35 p.m. / Transportation

Someday soon, a fleet of hydrogen fuel cell electric transit buses just like this will cruise the roadways of Humboldt. | File photo by Ryan Burns.

###

The Humboldt Transit Authority (HTA) is constantly looking for new, innovative ways to improve access to public transportation services here in Humboldt County. Its latest initiative: launching the North Coast’s first 15-minute intercity express line.

The California State Transportation Agency (CalSTA) recently awarded an $18.7 million grant to the HTA to fund the purchase of five fuel cell buses and the infrastructure needed to support “high-frequency” service, with buses arriving at stops every 15 minutes or less during operating hours. The goal is to ensure reliable service throughout the Redwood Transit System, allowing riders to board without checking a schedule.

“To ensure the success of this new service, its launch will be accompanied by the installation of new rebranded bus stop designs equipped with real-time signage and lighting and showcasing local art installations, and aggressive sustained marketing campaigns that build off the marketing work HTA and [the Humboldt County Association of Governments] HCAOG have completed to date,” according to the detailed summary of the project.

The grant, which comes from the state’s Transit and Intercity Rail Capital Program, will also help fund the first phase of the North Coast Zero Emission Operator and Maintenance Training Center, which includes classroom space, training simulators for bus drivers, mechanic training boards and various other zero-emission training tools.

The project is slated for completion in 2029. More information can be found in the press release below.

###

Press release from the Humboldt Transit Authority:

The Humboldt Transit Authority (HTA) has been awarded a $18.7M capital infrastructure grant from the California State Transportation Agency’s Transit and Intercity Rail Capital Program.

This project will:

- Install infrastructure needed to support Humboldt’s first 15-minute frequency service to be deployed on the Redwood Transit System;

- Enhance passenger safety and experience through improved bus stop designs that incorporate real-time arrival and departure information, improved lighting, and security enhancements;

- Develop standard bus stop designs that follow current design best practices, and integrate HTA’s new RideHumboldt branding;

- Commission public art installations at bus stops;

- Enhance the planned Eureka Intermodal Transit Center with the addition of state-of-the-art indoor and outdoor real-time arrival and departure information for all transit lines in the County, design and technology features to encourage use of the transit center as a community space, interactive and activating lighting to creatively increase safety, and commissioned public art installations;

- Kick start the first phase of HTA’s planned North Coast Zero Emission Training Center that will procure training equipment to advance HTA’s driver and mechanic training programs, construct a new training classroom, and facilitate collaboration with local high schools, colleges, and workforce development programs in support of regional zero emission vehicle training programs; and

- Procure additional fuel cell electric buses to grow HTA’s zero emission fleet in support of the new 15-minute frequency service.

“This is an incredible opportunity to expand our fleet of lower emissions vehicles, improve information for transit riders, increase frequency of service, and more. I’m thrilled to be part of the Humboldt Transit Authority team, and am so proud of our agency’s work to steadily increase the capacity for transit in Humboldt County!” - Natalie Arroyo, Board Chair, Humboldt Transit Authority.

HTA partnered with the Humboldt County Association of Governments who will provide project management and implementation support. This project is expected to contribute significantly to increasing transit ridership and decreasing vehicle miles traveled, two key targets in the County’s Regional Transportation Plan.

This project builds off HTA’s award in 2022 which kickstarted HTA’s transition to a fuel cell electric fleet. HTA is on track to receive it’s first fuel cell electric bus in spring of next year. This bus will be the first fuel cell transit bus in the nation with enough fuel capacity to drive 400 miles. HTA is currently in the procurement process for temporary hydrogen fueling to support this first bus, and for a permanent liquid hydrogen fueling station to support HTA’s additional buses planned for delivery in the fall of 2026. The liquid hydrogen fueling station will support both bus fueling and passenger car fueling. A fueling dispenser will be available to the public, providing a station that supports the Governor’s target of 200 hydrogen stations by 2026 serving light and medium-duty vehicles. HTA will also offer fueling to other local fleets interested in adopting fuel cell electric cars, delivery vans and other vehicle types.

This project also builds off HTA’s award in 2022 for a new intermodal transit center in downtown Eureka. The new transit center will be integrated with affordable housing and commercial spaces. It will support local and intercity fixed route services, on-demand services, taxis, bike and scooter share, microtransit, paratransit, and regional Amtrak services all centralized in Eureka’s Old Town district.

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Is Humboldt a ‘Climate Refuge?’

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Image: Stable Diffusion.

People often say that Humboldt County is a climate refuge. But what does that mean? And after Hurricanes Helene and Milton slammed the Southeast — including communities like Asheville, North Carolina, which was also described as a climate refuge — what is still safe in the age of climate-driven megastorms?

Luckily, we have Michael Furniss, adjunct professor at CalPoly Humboldt, and Troy Nicolini, Meteorologist-In-Charge at US National Weather Service, Eureka, on the show to discuss what is known about how climate change may affect Humboldt County. The good news: We are fortunate to have a very stable climate, even in the face of climate change, and that’s not likely to change much. The Pacific is likely to continue to act as our natural air conditioning. The bad news: Warmer temperatures elsewhere are going to increase moisture in the air and energy in storm events, bringing larger and more unpredictable weather. (But nothing like Hurricanes Helene or Milton.)

If we are likely to have desirable weather into the future, what does that mean for future development plans? We will save that for a future episode.

Want to learn more? Check these out!

- Troy Nicolini delivers the Humboldt Bay Symposium Keynote Address: Winds of Change, 2024.

- Is the North Coast a Climate Refuge? Michael Furniss at the Eureka Zoo lecture series, 2019.

- Understanding the 1964 Flood with Michael Furniss.

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: Eureka’s Groundbreaking, World-Famous Baby Orchestra

Unknown Author / Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024 @ 7:30 a.m. / History

This was a widely circulated photo of the Baby Orchestra. Front row, left to right, Stanley Widness, Dorothy Wade, James Boyias, Shirley Richardson, Richard Norman, Bill Lima. Second row. Jack Thompson, Gloria Moore, Arne Leskinen, Geneviève Ganson. Jack Lima, Brigitta Leskinen. Third row, June Gassaway, Joyce Haggard, Russell Running, Betty Russell, Violet Marsh, Blossom Fairchild, Norma Halvorsen. Back row, Norma Widness, Karl Moldren, instructor, and June Wade. Norma and June took turns as pianists and directors for the group. Photo via the Humboldt Historian.

###

The Historian has had mention of Eureka’s famed Baby Orchestra in previous issues but the material has been brief and lacking in some interesting details.

Thanks to Arne Leskinen, a former member of the orchestra now retired in Eureka after a career in sales, we have been able to piece together more information on a group that was once the talk of the town.

In gathering data on the orchestra, Arne has had the help of Norma (Widness) Myrland, another member of the group now living in Mesa, Arizona.

The orchestra, 19 tiny musicians, from 2 1/2 to 7 years of age, was organized in 1929 under the direction of Karl Moldrem and was called the Sherman Thompson Baby Orchestra. It promptly gained attention locally when the children played at churches and for various other groups and community functions. Within a year, the orchestra caught national attention through an RKO Pathe newsreel filmed at the Garden Court of Eureka Inn and pictures of the orchestra appeared in newspapers in the United States and Canada.

The Literary Digest, a popular national publication of that time, ran a Humboldt Times feature story on the orchestra complete with a photo. That story follows:

Not content with Yehudi Menuhin and Ruggiero Ricci, two prodigies of the violin, California produces a whole orchestra of infant players.

Some of our readers may have already made acquaintance of these musicians through the Pathe Sound News. They are looked upon as the possible salvation of domestic music, silenced by the radio and the phonograph. Eureka, California, is the well-named home of the organization, and The Humboldt Times, published there, looks to a world-wide imitation.

About twelve months ago, S.H. Thompson and G.W. Thompson of Eureka, with the aid of Karl Moldrem, violinist and teacher, conceived the idea of the formation of a baby orchestra to interest the parents in giving their children a musical education.

Today that group of nineteen tiny instrumentalists, ranging in age from two and a half years up to seven years old, has brought international fame to Eureka. Hundreds of letters from music teachers, schools of music, chambers of commerce in Eastern cities, and nationally known magazines, have made their way to Eureka inquiring about the tiny musicians. They are in demand at afternoon teas, lodge meetings, churches and luncheon clubs.

Recently the Pathe News company made a special trip to Eureka and took a sound-film, which is expected to show in all parts of the world. The picture of the orchestra is appearing daily in papers throughout the United States, Canada, England, and other countries. The enthusiasm created by their performance has become so great that countless cities are contemplating the organization of such groups, and parents are anxious to have their children learn how to play some instrument.

Although the idea of teaching mere babies how to play a musical instrument, and organizing a group of them to play together, was rather risky, the Thompsons ordered some tiny violins. They realized that it was highly essential that the baby violins be of the highest quality and material, and found it necessary to have them made in Europe. When the tiny instruments arrived they selected a group of youngsters to begin lessons.

Not a single one of the nineteen was able to read either ‘reading’ or music when they began practicing. The most difficult part of the entire effort was teaching the babies the first seven letters of the alphabet to identify the notes on the musical scale, and the first four numerals enabling them to count, according to Moldrem, their instructor. These fundamentals are necessary before note-reading can begin.

Music critics who have either heard and seen the orchestra play here, or have seen them in the Pathe News, have marveled at their team-work.

The intonation and uniformity of bowing shown by the babies has excited wonder.

While all the babies show remarkable development, three of them have become particularly proficient in their solo work. These are Dorothy Wade, James Boyias, and Shirley Richards. June Wade, nine years old, and Norma Widness, eleven, take turns as pianists and directors of the orchestra, so that the entire program can be presented by children.

Arne Leskinen recalls traveling around Humboldt County with the orchestra. One trip took him to the Town Hall at Crannell and in close proximity to a child that was to be his wife in later years. Mrs. Leskinen, then six-year old Lois Emenegger, was confined to her Crannell house when she would not consent to letting her mother pull a loose tooth as a condition for attending the orchestra program. She remembers shedding tears and hearing the music drift across the river from Town Hall.

Arne noted that the instructor had charisma, especially with the ladies, and was well liked. “Many cried when he left in 1930-31 for Hollywood.” While at Hollywood Studios, he worked on music for children and later left for New York City where he was involved in publishing violin instruction material.

Special pianists for the orchestra were Norma Widness, 11, and June Wade, 9.

Arne has offered the following information on some of the other orchestra members:

Dorothy Wade: Became a musician in the Los Angeles area and a studio violinist.

James Boyias: Took the stage name of Demetrius and became the most noted of the orchestra members. He moved to Berkeley to study in 1932-33 and toured South America on a concert tour at the age of 12. In 1941 he came back to Eureka and gave a benefit concert. Arne saw him in Atlantic City, N.J., in 1942 after he had left the Air Force. He played semi-pro baseball in Montana for awhile and then went to New York to study music for a year. He spent two years on a concert tour of the U.S., earning enough money to pay back his adopted parents for expenses on his behalf.

He returned to Eureka and worked for the Northwestern Pacific Railroad and later the Eureka Police Department before going into car sales. He enlisted again in the Air Force in 1955.

Brigitta and Arne Leskinen: She and Arne were cousins and the two played violin duets. She studied music at San Jose State College and went on to Washington, D.C., and became a concert mistress. She died in 1963. Arne gave concerts at the age of 10 or 12 at the old State Theatre, now occupied by Daly’s store and at Eureka Inn. He played until he was 15 and later made a career in sales. He was born in Berkeley and came to Eureka at the age of 4.

Jack and Bill Lima: Jack is a retired Humboldt State University professor who lives at Trinidad and Bill, the younger brother, is deceased.

Jack Thompson: Entered the insurance and real estate business in Eureka. He died in a car accident on Myrtle Ave. about 10 years ago.

June Gassaway Manfredda: Became an accomplished vocalist and is a resident of Arcata.

Stanley Widness, cousin of Norma Widness, lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

After Moldrem, the orchestra director, left, his assistant, Ralph Owen, took over and directed the orchestra. Arne lists three people from that group as Guy Keith, a businessman in Texas oil; Ted Hash, a Eureka longshoreman, now deceased; and Helen Mattila Barnett, who, with her husband, operated Ducks Market. Owen later organized a baby orchestra in the Dunsmuir area.

Others in the Eureka orchestra included Shirley Richards, Norma Halvorson, Gloria Moore, Geneviève Ganson, Joyce Haggard, Russell Running, Betty Russell, Violet March, Blossom Fairchild, Jack Madden and Millicent Human.

Apparently a need was felt for a second baby orchestra in Eureka and this group was organized under the direction of Professor E.J. Bonner on Oct. 13, 1931. The Bonner orchestra was featured in the January-February 1981, issue of the Historian. Additional baby orchestra data appeared in the March- April 1981, issue of the Historian.

###

Ed. note (from the Outpost): Moldrem went on to found baby orchestras across the land, notably in Los Angeles and New York City, which earned him a write-up in both Time and the New Yorker.

###

The story above is from the May-June 1987 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

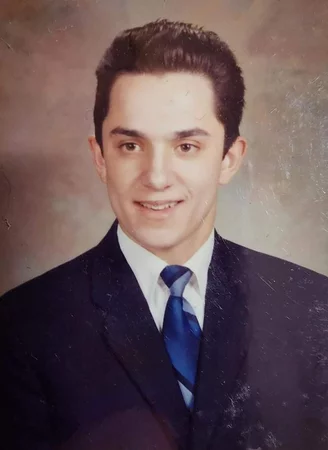

OBITUARY: Leon Freitas, 1953-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Oct. 26, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It

is with a heavy heart that we announce the passing of Leon Freitas on

Oct 16, 2024.

Leon was born June 12, 1953 on the Island of Flores, Azores where he was the eldest son of Pedro and Maria Freitas.

He migrated to America with his family in 1966 but never forgot his Portuguese roots, learning from a young age about hard work, dedication and love of family. He had a lot to overcome being deaf, moving to a new country, learning a new language, all the while working in the fields and dairies helping provide for his family, which he always did without complaint.

In 1970 he and his family moved to Eureka for work and he attended Eureka High school, graduating in 1972. After high school Leon went to work for Arcata Redwood, performing many different jobs within the mill. No matter what job he held you could always count on Leon to put 100% effort into his work. If he had work in front of him he was relentless until it was completed to his satisfaction. After he left employment with the company as a cleanup person it took two individuals to complete the work Leon did by himself, which is a testament to his upbringing, dedication and pride in his work.

In his later years Leon had a lot of various health issues that eventually led to him being placed in the care of the Carol Sund Butler Valley Home and Eureka Rehabilitation and Wellness center. Special thanks go out to the Redwood Coast Regional Center for helping the family throughout this period. The family wants to express their gratitude to everyone who helped Leon with compassionate care they all provided during his stays was very appreciated!

Leon came from a large family. Father Pedro is deceased, Mother Maria, Sisters Maria Owsley, Cecilia Ricci, Fatima Wright, Connie Smeal, Brothers Joe, Pedro, Danny, Tony, Manuel, Frank. Leon had one Son Kenneth Charles Freitas (KC) who currently resides in Washington State. And numerous nephews and nieces.

A celebration of life will be held at the home of Maria Freitas, located at 870 Allard Ave in Eureka on Oct. 26 at 2 p.m.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Leon Freitas’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.