Sumo, One of the Sequoia Park Zoo’s Original Red Pandas, Has Died

Andrew Goff / Wednesday, Aug. 21, 2024 @ 7:12 a.m. / Wildlife

Sequoia Park Zoo release:

Sequoia Park Zoo is deeply saddened to announce the passing of Sumo, our beloved red panda.

Although not entirely unexpected due to his advanced age, it is no less heartbreaking for the staff, volunteers, and guests who loved and cared for him.

At 15 years old, Sumo far exceeded the typical wild lifespan of 8-10 years, and he was considered geriatric for a red panda. In fact, out of over 800 red pandas documented in human care, Sumo was in the top 4% for age - a testament to the exceptional care he received throughout his life at the Zoo.

In recent years, Sumo had been treated for common age-related concerns, including joint pain, dental issues, and loss of muscle tone in his hind legs. Animal care staff worked with Sumo to meet the changing needs of an older animal, which included modifications to the habitat, physical therapy, and medication for pain management. Last week, Sumo suffered a rapid decline in health and, despite the best efforts of his care team, veterinary staff were unable to stabilize him. A standard necropsy procedure will be conducted to determine the cause of death.

Sumo was born at the Denver Zoo in 2009 and arrived at Sequoia Park Zoo with his brother Shifu in 2010 to the delight of our community. As the first red pandas to call the Zoo home, Sumo and Shifu inspired an instant connection to animals and a love of red pandas in everyone who met them.

Red pandas are an endangered species supported by the AZA’s Species Survival Plan, and in 2013 it was determined that both brothers should start a family. This exciting news meant that Shifu was transferred to another zoo, while Sumo stayed in Eureka and Stella Luna moved to join him. Sumo and Stella Luna had two litters during their time together, increasing the red panda population by three beautiful daughters: Mohu, the eldest, followed by Masala and Cinni.

Sumo met many adoring red panda fans as an animal ambassador, and he was often eager to participate in special VIP encounters - especially when grapes were involved! Sumo was one of the most accomplished animal artists at the Zoo, and some guests may be lucky enough to have an original Red Panda Painting made by Sumo walking through paint and onto a canvas.

Sumo engaged with and educated thousands of guests during his time at Sequoia Park Zoo, and he helped share the story of red pandas and their need for conservation. We invite our guests to share a photo or memory as we celebrate the one-and-only Sumo - the original red panda resident at the Zoo.

PREVIOUSLY:

BOOKED

Yesterday: 9 felonies, 10 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 13

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Snow Could Impact Travel From Del Norte to Mendocino and from Eureka to Redding

RHBB: CDFW Accepting Applications for Spring Elk Hunts in Del Norte County

RHBB: Shasta-Trinity & Six Rivers National Forests seeking public input on OHV grant applications

TODAY in SUPES: Board Approves Tiny House Village Ordinance, Sends Concerned Letter to SF Mayor; Latest Homelessness Count Revealed

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 5:13 p.m. / Homelessness , Local Government

A tiny home village from the county staff report. | Image via County of Humboldt.

###

In an effort to expand low-cost housing options and alleviate our region’s chronic homelessness, the Humboldt County Board of Supervisors today passed a package of ordinances that together will allow tiny home villages and emergency housing villages in certain residential and commercial zones.

The Tiny House Village Ordinance, which was developed by staff and fine-tuned over the course of three planning commission meetings, allows for groups of self-contained tiny homes, each with their own kitchen and bathroom facilities, as well as dependent unit villages, where three or more sleeping units share central kitchen and bathroom facilities.

A pair of ordinances — one for the inland areas and one for the coastal zone — create design standards and regulate such things as water/sewer connections, parking, pets (up to two cats/dogs per unit), bike lockers, power sources and more. Short-term rentals (like Airbnb) are not allowed, and power is allowed with grid connection, renewable power or generators, though Acevedo noted that there are noise and storage standards for the latter. Road access need to meet fire safety regulations for fire truck access.

These villages are intended for permanent residential use, and standards spelled out in the ordinance require privacy between units, common areas and, for the dependent unit villages, property management. The ordinance allows for up to 30 units per acre, with no minimum parcel size, and applicants could be allowed even more units with a density bonus.

County planner Megan Acevedo, who delivered the staff report, showed a map of more than 700 qualifying parcels that fall within half a mile of a bus stop.

The Emergency Housing Village Ordinance — which also has inland and coastal zone versions — allows for “alternative lodge parks,” which require a use permit. The living quarters here — defined as hard-sided and -roofed structures with living space and possibly a bathroom but no kitchen — only need to meet basic California Building Code requirements, not the full Uniform Building Code. Allowable housing types include movable houses, tiny homes, mobile homes, RVs and trailers.

Such emergency villages will only be allowed while the county has an active shelter crisis declaration. (The current one has been in place since 2022.) Once the shelter crisis is declared over, these sites will need to be removed. The emergency villages, which must be connected to public water and sewer systems, are intended specifically for people experiencing homelessness, and they can only be operated by a government agency, religious institution or nonprofit.

After the staff presentation, Second District Supervisor Michelle Bushnell voiced concerns about tiny home villages and emergency shelter villages being allowed in downtown Garberville without a public review process. She noted the struggling economy in SoHum and said, “If you create those housing opportunities in a community and then you have no commercial in that community … what are you creating?”

Planning and Building Director John Ford told her that state law already allows residential developments in commercial zones by right, and tiny home villages are intended to be an alternative permanent housing type.

Requiring public input to permit housing “can become a very painful process that actually discourages [applicants] from even beginning that process,” Ford said.

First District Supervisor Rex Bohn said he’s worried about the potential for massive tiny home developments to pop up in certain locations, such as the McKay Ranch subdivision on the outskirts of Eureka.

“So could they actually build 1,200 tiny homes out there and set up a nonprofit?” he asked.

Ford said that since some parcels in that development are zoned for multi-family residential, it’s conceivable that something like this could go there.

Despite these concerns, the supervisors acknowledged the longstanding issues around homelessness and wound up approving the ordinances unanimously.

Homeless numbers decline a bit

The latest “Point-in-Time” count of people experiencing homelessness estimated that there were 1,573 such people in Humboldt County on the night of January 22, 2024. That’s a 4.4 percent decrease from the previous count, conducted in 2022, and a 7.6 decline from 2019, according to Robert Ward, the Humboldt Housing and Homelessness Coalition coordinator.

Of that latest total, 551 people were considered “chronically homeless,” with almost 80 percent of those being unsheltered, Ward said. Contrary to many stereotypes, only about 412 of the roughly 1,400 homeless adults reported having a significant mental illness, though Ward said that’s a lower standard than what the county uses to qualify people for mental health services.

Four hundred eighty five of the adults reported a substance use disorder, and 95 percent of those folks were unsheltered.

Families with children saw a significant increase in the count, though Ward said that uptick was partly due the first-time inclusion of people in the CalWORKS temporary homeless assistance motel voucher program, the Humboldt domestic violence services shelter program and a new Hoopa tribal shelter.

“Those folks were there before, but we just didn’t have data in the past,” Ward said.

There was a large decline in the number of homeless veterans tallied, with just an estimated 87 in this year’s count. Ward said he doesn’t know why that is and couldn’t offer any theories.

American Indian or indigenous folks accounted for 13.67 percent of the total tally, which is more than double that group’s share of the general population, according to Census data.

There are significantly fewer unsheltered people in Eureka and especially Southern Humboldt, while the number in Arcata climbed dramatically from previous counts.

Fifth District Supervisor Steve Madrone had some questions about the methodology, noting that the vast majority of people experiencing homelessness in McKinleyville are on private property, most of which is considered off limits to volunteer counters.

Letter to San Francisco Mayor London Breed

Toward the end of the meeting, Connie Beck, director of the county’s Department of Health and Human services, presented a draft letter that her department recommended sending to San Francisco Mayor London Breed regarding that city’s new Journey Home program, which offers homeless people one-way tickets to other jurisdictions “without verifying access to housing, family support or employment,” according to the letter.

A recent story in the San Francisco Standard identified Humboldt County as one of the top three destinations for homeless people given bus tickets within California, though, as the Outpost reported yesterday, there have only been 25 such people (sent anywhere in California) since the program launched last September, and the number who’ve been sent here is so small that the San Francisco Human Services Agency said an exact number could be identifying.

Meanwhile, Humboldt County helps relocate “an average of nine people a month” through its own Transportation Assistance Program, according to DHHS spokesperson Christine Messinger.

Still, Beck and other county officials are concerned about an influx of more homeless people with tenuous ties to the community, and the letter urges Breed “to ensure that Journey Home participants have the support they need to obtain housing and employment before they receive transportation assistance to Humboldt County.”

Fourth District Supervisor Natalie Arroyo said she felt the letter was “a little bit of overkill” in expressing dismay about some people coming to Humboldt County and in submitting a formal request for more information under the California Public Records Act.

Third District Supervisor Mike Wilson also voiced concerns, saying he would have preferred if county staff reached out to employees in San Francisco to request more information on the policy before drafting a public letter.

“I kind of feel like it just misses a step,” he said of the letter.

But DHHS staff said San Francisco has made a “dramatic change in their policy” that could result in far more homeless people being sent here. Bohn agreed, saying the city has removed “90 percent of their criteria” for putting someone on a bus. He advocated for sending the letter.

“I don’t want to hurt San Francisco’s feelings, but on the other hand, I don’t care,” Bohn said.

Bushnell and Madrone both said they’re okay with the letter’s content, with Bushnell saying her constituents have expressed a lot of concern about the matter. Bohn suggested excising the Public Records Act request from the letter.

Bushnell made a motion to allow Beck and Bohn to rework the letter as discussed and then send it. Wilson seconded the motion, and it passed unanimously.

Additional Details Released on This Morning’s Eureka Boat Fire

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 3:15 p.m. / Fire

PREVIOUSLY:

# # #

Humboldt Bay Fire press release:

At 0859 hrs on August 20, 2024, Humboldt Bay Fire responded to a reported Boat Fire at 1 Marina Way at the Eureka Public Marina. Humboldt Bay Fire responded with one Ladder Truck, three Engines and one Chief Officer. The first arriving unit found black smoke coming from the boat. One occupant had been pulled from the fire prior to fire personnel arriving on scene. The occupant had minor injuries.

Fire Crews quickly went to work extinguishing the fire and treating the injured occupant. It was also noted that a dog had jumped from the vessel after the boats ignition and was not injured. The dog remained with Fish and Wildlife personnel until EPD animal control took over care. There were no further civilian injuries and no Firefighter injuries.

The boat sustained major damage and is considered a total loss with damages estimated at $20,000. The cause of the fire is under investigation.

A total of 13 Firefighters and one Volunteer Support unit responded to this incident. HBF would also like to thank the Eureka Police Department, City Ambulance, and Fish and Wildlife who also assisted in stabilizing the incident.

HBF was able to extinguish the fire in a manner that prevented the boat from sinking or causing fuel, oil, or other contaminates into the bay. Life and safety are operational priorities to us and we also place a heavy tactical priority on protecting the environment. Today’s response and mitigation was a good demonstration of those operational priorities. Humboldt Bay Fire reminds the community to call 9-1-1 immediately during any emergency, no matter the location.

Farewell to The Independent, the Free, Locally Owned Newspaper That Has Served Southern Humboldt for Decades

Hank Sims / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 11:31 a.m. / Media

The Independent’s offices, in downtown Garberville, can be seen in this photo. It’s the orange bit between the yellow bit and the blue bit. Photo: Ellin Beltz, public domain. Via Wikimedia.

A sad day for lovers of local newspapers. After years of facing not only the general decline of the industry worldwide, but also the collapse of the southern Humboldt economy in particular, the Garberville-based free weekly The Independent is closing its doors. Its last issue is on stands now.

Every publication, if it is successful, creates its own little world, which is a reflection in miniature of the world it serves. The Independent excelled at this. It usually led with a big, beautiful nature photograph of some place or creature in SoHum. Elsewhere on the front page were news reports from experienced, professional reporters like Daniel Mintz and Keith Easthouse. In the back pages — always the soul of any newspaper — you got various voices from the community, including most prominently that of Ray Oakes, the octogenarian whose column was the paper’s anchor for most of its run.

It will be missed. KMUD’s Lauren Schmitt had a nice talk with Joe Kirby, the Independent’s editor, on last night’s broadcast. “People are almost, just, kinda over it,” Kirby says of print journalism in general, which is the saddest and truest thing you’re likely to hear today.

Listen to the KMUD interview below.

(VIDEO) One Taken to Hospital After an Explosion on a Boat in the Eureka Marina

Ryan Burns / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 9:35 a.m. / Fire

###

One person was taken away in an ambulance this morning with minor injuries following an explosion on a boat in the Eureka marina.

Several Humboldt Bay Fire engines responded to the scene around 9 a.m. A bystander pulled the injured person out of the boat, according to the Outpost’s Andrew Goff, on the scene. The person was stable and walking after the explosion.

A dog jumped out of the boat after the explosion and was taken into the custody of the California Department of Fish and Wildlife. The Outpost is very happy to report that, while the dog was spooked, it’ll be JUST FINE!

Here’s a photo of the cute pooch:

Photo by Andrew Goff.

BOISE FIRE UPDATE: Fire Tops 12,000 Acres, Though Growth Has Slowed and Rain is On the Way

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 8:51 a.m. / Fire

The Boise Fire as of this morning. The squares are satellite-detected hotspots: Red squares were detected within the last six hours, orange within the last 12 and yellow within the last 24. Automatic updates here.

Press release from the Boise Fire management team:

Quick Facts

- Acreage: 12,125

- Containment: 13%

- Cause: Under investigation

- Crews: 29

- Engines: 63

- Dozers: 9

- Helicopters: 15 + UAS

- Fixed wing: available as needed

- Total resources: 1,085

- Information: Click here.

Headlines

- TRAFFIC CONTROL started last night on the Salmon River Road between Wooley Creek and Nordheimer Flat and will be in place 24 hours per day. The traffic will leave on the hour every hour westbound, and on the half hour every hour going eastbound.

- A public meeting is planned at the Forks of Salmon Community Club TODAY at 5 p.m. This meeting will not be livestreamed.

- Fire information phone: 707 572-4860 or email at 2024.Boise@firenet.gov

- Get all your Boise Fire information in one mobile-friendly place! https://linktr.ee/

- Evacuations are in place for the Boise Fire for residents near the fire area in Humboldt County. For the most current evacuation information please visit the Boise Fire linktree or visit—

- Humboldt County: https://humboldtgov.org/356/

- Siskiyou County: https://www.co.siskiyou.ca.us/

Leader’s Intent:

- The Boise Fire is being managed with a full suppression strategy.

Operational Update:

The fire showed an uptick in visible activity yesterday as vegetation continued to dry. While there was little growth outside the current perimeter, islands of unburned vegetation continue to ignite and smolder. Overnight, crews patrolled the fire adjacent to communities and infrastructure and continue to do some minor firing east of the north fork of Red Cap Creek to further strengthen containment in that area.

Today, crews will continue with their previous work assignments, building and improving proposed indirect line along Orleans Mountain Ridge east toward Nordheimer and south from Nordheimer to Mullins Camp through Horn Creek Gap. From Mullins Camp they are working up the Salmon Summit Trail to the northwest corner of the fire.

They also continue to look for contingency lines off the primary indirect line, and to look for opportunities for suppression closer to the Salmon River. They have begun structure assessments and preparation should it be necessary to protect the structures along the Salmon River Road.

Weather and Fire Behavior:

One more warm, dry day today is expected to be followed by increasing cooler and moisture conditions through next weekend. Another chance for wetting rain is expected to come into the fire area Tuesday into Wednesday, bringing with it a slight chance of thunderstorms. This will be followed by another stronger system later in the week. Temperatures are expected to increase considerably across the fire area by this time next week.

Photo: Fire management Facebook page.

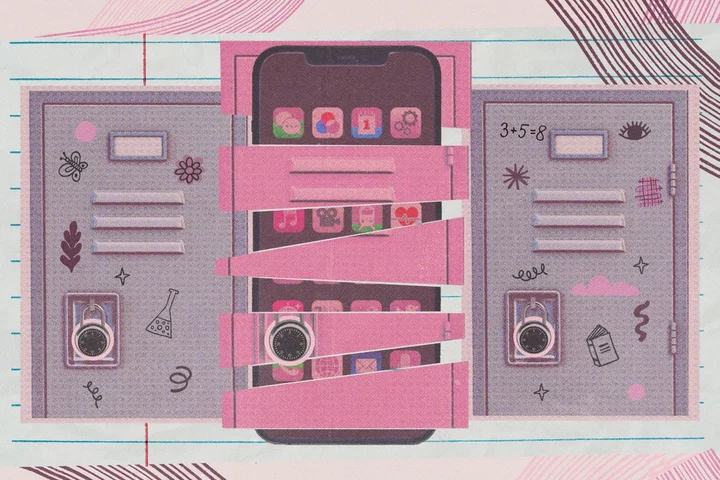

More California Schools Are Banning Smartphones, but Kids Keep Bringing Them

Carolyn Jones and Khari Johnson / Tuesday, Aug. 20, 2024 @ 7 a.m. / Sacramento

Illustration by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters; iStock

At Bullard High School in Fresno, it’s easy to see the benefits of banning students’ cellphones. Bullying is down and socialization is up, principal Armen Torigian said.

Enforcing the smartphone restrictions? That’s been harder.

Instead of putting their devices in magnetically locked pouches, like they’re supposed to, some kids will stick something else in there instead, like a disused old phone, a calculator, a glue bottle or just the phone case. Others attack the pouch, pulling at stitches, cutting the bottom, or defacing it so it looks closed when it’s really open. Most students comply, but those who don’t create disproportionate chaos.

“You should see how bad it is,” Torigian said. “It’s great to say no phones, but I don’t think people realize the addiction of the phones and what students will go to to tell you ‘No, you’re not taking my phone.’”

Bullard, which began restricting phones two years ago, is a step ahead of other schools around the state that have moved recently to prohibit cellphones in classrooms. Bullard and other pioneering schools offer a preview of how such bans might play out as they become more common. Educators who have enacted the smartphone restrictions said they help bolster student participation and reduce bullying but also raise challenges, like how to effectively keep phones locked up against determined students and how to identify and treat kids truly addicted to their devices.

Citing Bullard as an example, Gov. Gavin Newsom last week urged school districts statewide to “act now” and adopt similar restrictions on smartphone use, reminding them that a 2019 law gives them the authority to do so. Los Angeles Unified, the nation’s second-largest school district, recently approved plans to ban phones in January. One bill before the state Legislature would impose similar limits statewide while another would ban the use of social media at school. Another would prevent social media companies from sending notifications during school hours as part of a broader set of regulations intended to disrupt social media addiction.

Calls to limit how students use smartphones are driven in part by concerned educators. A Pew Research Center survey released in June found that 1 in 3 middle school teachers and nearly 3 in 4 high school teachers call smartphones a major problem. During school hours in a single day, the average student receives 60 notifications and spends 43 minutes — roughly the length of a classroom period — on their phone, according to a 2023 study by Common Sense Media.

There is growing pressure to protect young people from excessive screen time generally:

- In June, U.S. Surgeon General Dr. Vivek Murthy urged Congress to require social media companies to place warning labels on their content in order to protect young people

- Attorneys general from 45 U.S. states filed lawsuits against Meta for failing to protect children

- Released in March, the popular book The Anxious Generation correlates declining mental health among young people with smartphone adoption and encourages parents to demand school districts ban smartphones until high school

College Park High School students relax in the Wellness Center, which provides a quiet environment as well as meditation, peer support and social services for students. Pleasant Hill on March 15, 2024. Photo by Manuel Orbegozo for CalMatters

The moves to limit smartphone use in California put it near the forefront of an increasingly national trend. In New York, Gov. Kathy Hochul has reportedly been mulling a statewide school smartphone ban for several months now. Florida, Ohio, and Indiana have all imposed some degree of statewide restrictions on phones in schools, and several other states have introduced similar legislation. Education Week in June said 11 states either restrict or encourage school districts to restrict student phone use.

In San Bernardino, ban leads to higher teacher satisfaction

Teachers have had classroom phone policies for years; what’s new at schools like Bullard are that their bans are blanket, campus-wide restrictions. Many of the schools that moved early to adopt such bans are smaller and charter schools, like Soar Academy, a TK-8 charter school with 430 mostly low-income students in San Bernardino. Like Bullard, it also found enforcement of its ban was tough. Suspending students wasn’t an option. Neither was yanking phones from students’ hands. That left an honor system, which relied on students’ willingness to accept that smartphones and social media are harmful to their mental health and a distraction from learning.

“The key was that we needed 100% buy-in from teachers. There couldn’t be a weak link,” said Soar principal Trisha Lancaster. “It was scary, because we weren’t sure it was going to work. But we were determined to try.”

Lancaster said it also helped not to give parents or students a choice in the matter. The school simply presented the new policy, alongside ample research on the harmful effects of cellphones and social media on young people, and made it clear what the punishments would be.

For the first violation, staff would keep a student’s phone for the day and call their parents. Punishments would escalate until the sixth offense, when a student would have to meet with the school board, whose members might suggest the student enroll elsewhere.

“It was scary, because we weren’t sure it was going to work. But we were determined to try.”

— Trisha Lancaster, principal, Soar Academy in San Bernardino

At Soar, the idea originated at the end of the 2022-23 school year, when teachers said they were fed up with distracted students and an overall dispiriting school climate. Students, Lancaster said, “had lost their social skills.”

So the staff decided to ban phones during class, at recess, at lunch and after school — essentially, all times except when in a special area where parents or others can pick them up from school. Students must keep phones off and in backpacks when they are not permitted.

The first year of the ban went smoother than expected, Lancaster said. Some students and parents protested, but most understood the policy was in students’ best interests. Test scores didn’t budge much, but at the end of the school year, a survey of teachers showed much higher job satisfaction than they recorded previously. And walking across campus, the improvements are obvious, Lancaster said.

“Everyone on campus is so much happier. You see kids actually socializing, problem solving, enjoying themselves,” Lancaster said, choking up as she described the school atmosphere. “It’s true, it’s one more thing to enforce. But education matters, and now kids are learning. That’s the No. 1 reason we did this.”

Bans from San Mateo to San Diego

Soar’s experience has been mirrored on a larger scale in the San Mateo-Foster City School District, which serves 10,000 students at 21 TK-8 schools south of San Francisco. After a full-time return to campus in 2022, teachers in the district found many students were “interacting intensely with cellphones in a way we didn’t see before the pandemic,” said superintendent Diego Ochoa, and so the school district adopted a smartphone ban for four middle schools in 2022.

Administrators were convinced to do so following a trip to a nearby high school with a smartphone ban. There, they saw students speaking to each other and looking at one another during break time instead of their phones.

Ochoa said the benefits of locking smartphones away is evident from improved test scores and an anonymous annual student survey that found a decline in depression, bullying, and fights in the 2023-24 school year relative to prior years. But saying the smartphone ban led to those benefits is tricky because they could have also been caused by other policy changes that happened at the same time, including a ”restorative” approach to discipline that relied less on detention and suspension and more on support from counselors. Still, when students were surveyed specifically about the policy and the biggest difference in their education since it was put into place, they said that they pay more attention in class.

A sign that reads “no phone zone” in English teacher Jen Roberts’ class at Point Loma High School in San Diego on May 3, 2024. Photo by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters

Ron Dyste also implemented a smartphone ban and, like Ochoa, recommends them. Dyste is principal at Urban Discovery Academy, a TK-12 charter school in San Diego, which banned cellphones during the 2023-24 academic year amid an uptick in bullying, harassment and anxiety among students, staff told CalMatters. Nearly 90% of discipline cases, across Urban Discovery Academy and a school where he worked previously, could be traced to misuse of phones or social media, including students filming fights, spreading nude photos of classmates and encouraging students to kill themselves.

“I may never get some of those images out of my head. It’s horrible, what kids can do to each other,” Dyste said. “The damage to our kids and our communities is real.”

Dyste got the idea to ban phones when he and his wife went to a Dave Chapelle performance where audience members were required to secure their phones in locked pouches.

“My wife said, why don’t we do this in schools?” he said. “We knew we had to do something.”

Over last summer, the school sent out notices to families about the new policy, explaining the rationale. Some students complained, but parents were thrilled, Dyste said. And the improvements in campus climate were almost immediate.

“The damage to our kids and our communities is real.”

— Ron Dyste, principal, Urban Discovery Academy in San Diego

Instead of “hiding away with their screens,” said Jenni Owen, the school’s chief operations officer, students spent their breaks talking, dancing, playing volleyball, and having fun. They developed empathy and a sense of community, she said.

At the end of the academic year, the school logged zero fights. The previous year, the school’s suspension rate was 13.5%, almost four times the state average.

“For schools that are wondering if they should take this on, I think the answer is, we have to,” Dyste said. “If we don’t educate kids on how and when to use this technology, we’re going to continue seeing a rise in suicide, sexual harassment, and anxiety.”

State legislators have recognized the importance of healthier technology use among children. California students are supposed to learn about “appropriate, responsible, and healthy behavior… related to current technology” under a media literacy law passed in October.

To pouch or not to pouch

To enforce smartphone bans, some schools rely on smartphone lockers or locked pouches like the kind Dyste saw in use at the Dave Chappelle show.

He tried using locked pouches from the Los Angeles-based company Yondr but encountered numerous issues. Some kids were breaking and smashing the pouches to open them, or they’d listen to music all day by connecting their earbuds to their locked-away phones using Bluetooth.

“We had to return what was left of the equipment,” he said. Instead of going with Yondr, which wanted $6,000 to cover 110 kids, Dyste found clear, plastic phone lockers on Amazon that cost $50 each and put one in each classroom.

Yondr told CalMatters: “Our pouches are designed to withstand heavy-duty usage, and we are continuously working to improve the durability of our solution. However, there will always be students who try to push boundaries, especially when policies are initially rolled out. For this reason, it is critical that our team works directly with districts and administrators in rolling out the Yondr Program, to ensure that the most effective policies and procedures are implemented for successful school-wide adoption. Without adherence to strong policies, schools may struggle with student compliance.”

Soar Academy also considered purchasing Yondr phone pouches but was discouraged by the $19,000 price tag.

The San Mateo-Foster City School District paid $50,000 to obtain Yondr pouches for roughly 3,000 students. To use them, staff hand out pouches at school entryways each morning, then students swab the pouch over a demagnetizer to unlock the pouch at the end of the day. Kids who want an exception to the rule — for a family emergency for example — must come to the school front office and ask for permission.

Yondr pouches come with a hefty price tag, Ochoa said, but he thinks it’s worth it to improve student focus.

“Call up five random superintendents, I don’t care where they’re at and ask them, how much would you spend to have your students pay more attention? It’s worth millions,” he said.

Mixed feelings among students

Whether phones get locked in a clear box or a silver pouch, Oakland High School senior Leah West said she finds it punitive to require students to lock their phones away before they have broken any rules with the devices. While Oakland High School does not have a blanket smartphone ban, her former English teacher sometimes locked student phones in Yondr pouches.

“We should be given a chance to prove ourselves,” she said, adding that such an approach can motivate a rebellious streak in students like her who like freedom and don’t like when she isn’t trusted to make a responsible decision.

Louisa Perry-Picciotto, who graduated from high school in Alameda in June, said students with jobs rely on their phones for work updates and all teens use their phones to communicate with their friends.

Still, she’s grateful her parents didn’t get her a smartphone until she was in eighth grade.

“I get distracted easily, and without a phone I was a lot more connected to the world,” she said.

Leah West, 17, in Oakland on Aug. 16, 2024, is in 12th grade at Oakland High School. Photo by Florence Middleton, CalMatters

Edamevoh Ajayi, who is a junior at Oakland Technical High School, said there’s no question some students don’t pay attention in class because they’re busy texting or playing games. Those students would definitely benefit from rules surrounding cellphone use like the kind being implemented at her school this year.

But she feels like she has a strong sense of self-control and a desire to learn, and doesn’t need a phone ban.

“When they take away my belongings, I feel like I’m being treated like a child,” she said. At her school, policies vary by classroom. In general, students are free to use their phones between classes and at lunch.

When students use their phones in class it can be frustrating for everyone else, said Fremont High School science teacher Chris Jackson. It puts teachers in a tough position: Either ignore that student and carry on for the sake of the students who are listening or disrupt learning for all students and confront them.

In the long run, Jackson said he’s worried that Black and brown students, who have historically faced higher rates of punishment than other students, will again bear the brunt of disciplinary actions related to smartphone bans. Rather than punishment, Jackson would prefer to see solutions that address root issues like addiction that lead students to use their devices in violation of the rules. So no matter what policy school districts adopt, he wants the focus to remain on teaching students digital literacy and how social media can be a risk to their health.

Course corrections

Some schools who helped pioneer smartphone bans have reassessed their initial approach.

This year, Bullard is changing its policy to allow students to access their smartphones at lunch time. Torigian said school administrators wanted to make room for important communications, for example by allowing students who pick up younger siblings to text with their parents. They also hoped the looser rules would encourage more students to comply with the ban.

If kids don’t comply, teachers call parents, and if they still refuse they’re sent to what the school calls the re-engagement center. Starting last month, California began prohibiting suspensions for “willful defiance.” Torigian believes that schools need an exemption from the policy in order to enforce smartphone restrictions. He wants it back because he said he needs a way to hold kids accountable.

“That’s why the governor’s got to give us some leeway on this willful defiance; you can’t do one [smartphone restrictions] without the other.”

“Our teenagers told us, ‘you forgot to explain why we’re doing this.’”

— Diego Ochoa, superintendent, San Mateo-Foster City School District

Ochoa said if he had to do it over again in San Mateo-Foster City he would devote more time to explaining to students why they adopted such a policy before putting it into place. Getting a smartphone is a big deal for middle school students, a milestone for adolescents that represents more freedom and autonomy, and it’s counterproductive for the school environment if they feel punished or something they value is taken away with little explanation.

“Our teenagers told us, ‘you forgot to explain why we’re doing this,’” he said, adding that even if a small percentage of kids violate the policy it can be really harmful academically and to school culture. “Even with your conviction to implement a policy like this, spend the time developing the language around the policy and explaining it to your students.”

Common Sense Media CEO Jim Steyer, whose nonprofit is focused on how children use media and technology, agreed that it works best to explain to kids why a rule to limit smartphone access at school is necessary. Parents and teachers need the same explanation so that they can help enforce some restrictions in order to keep kids safe and healthy.

“Any even remotely engaged parent is going to want their kid to do well in school, and is going to want them to understand why phones and social media platforms get in the way of learning and can be really distracting and can affect your mental health,” he said.

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.