OBITUARY: Robert ‘Bob’ Palmrose, 1931-2024

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Aug. 29, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Robert

“Bob” Palmrose, age 93, passed away on July 1, 2024, in Eureka. A

native Californian, Bob was born April 11, 1931, at the French

Hospital on Geary Street in San Francisco. At the time, his father

had a job in San Francisco, due to the closure of Hammond Lumber

Company in Samoa, California. Shortly after Bob’s birth his family

returned to Samoa.

Bob attended local schools: Marshall Grammar School, Eureka Junior High, and Eureka Senior High, graduating in June 1948. From a young age Bob was industrious, mowing lawns with a push mower for two neighbors for a quarter each and manually setting pins at the Eureka Bowling Alley. For two years, he delivered the Humboldt Standard newspaper and for two summers the Chronicle, Examiner and Call Bulletin all by bicycle. He also worked as a “Printers Devil” at Eureka Printing Company doing light printing jobs, delivery, and cleaning of the presses.

At age 15, while in high school, he started working part-time at Safeway, transitioning to full-time employment after graduation.

Bob served in the U.S. Army, undergoing Basic Training at Camp San Luis Obispo, CA, before being shipped to Korea. He was assigned to the 40th Div. HQ & HQ Btry, Arty, on the central Front M.L.R. from August 1952 to August 1953. After returning to the U.S., he was stationed at Ft. Lewis, WA, and released from active duty on December 7, 1953, with the rank of Staff Sergeant. He received several awards for his service including the Army Good Conduct Medal, National Defense Medal, Korean Service Medal with three battle stars, United Nations Medal, the Republic of Korea Presidential Unit Citation, and the Korean Service Medal from the Korean Government (1999). He also received the Ambassador of Peace Medal presented by Korean Veterans and the Korean Government to all allies who revisited Korea during the 50th anniversary of the Korean conflict.

After his military service, Bob returned to his Safeway career and attended Humboldt State College. He dedicated 40 years to Safeway, including time spent in military service, and eventually served as a manager for 25 years at stores in San Francisco, Arcata and Eureka until his retirement in 1986.

Bob was an active community member, participating in the Rotary Club of Arcata, Rotary Club of Southwest Eureka, Arcata Chamber of Commerce (Board Member), Citizens Advisory Board , Humboldt Harbor Development Committee, Eureka Heritage Society (Board Member), Humboldt County Historical Society (President), Humboldt Bay Council #440 Navy League of the U.S. (Life member & President), Veterans of Foreign Wars (Life member at Large), Redwoods Chapter #176 Korean War Veterans Assoc (Vice President), National KWVA, Elks Lodge #652 Eureka, Humboldt County Pioneers, Native Sons Parlor #14 Eureka, Runeberg #102 Eureka, Horseless Carriage Club of America, Studebaker Drivers Club, Metropolitan Owners Club of North America, Willys-Overland Knight Registry and Humboldt Chorale H.S.U.

Bob was a train enthusiast and worked on the Steam Donkeys at Fort Humboldt in Eureka. He assisted with the restoration of the Saint George Reef Lighthouse located 8 miles off the coast of Crescent City in 1983. He was also involved in moving, and later painting, the Table Bluff Lighthouse to Eureka’s Woodley Island Marina in 1987.

In addition to the many organizations, Bob also enjoyed traveling, photography, gardening, antique automobiles, and spending time with his family. He took pleasure in singing throughout Europe with the HSU Chorale and dancing at many California jazz festivals.

Bob was preceded in death by his first wife of 36 years, Margie Joann (Davis) Palmrose (d 1989), their first daughter Janice Elene Gonsalves (d 1994), their third daughter Kathryn Eileen Palmrose (d 2015), his second wife of 26 years, Yvonne Jeanne Holmes (d 2017), his son-in-law Terry Brightman (d 2022), his sister Janice, his parents Gunnar A. Palmrose and Marion (Vallerga) Grubbs, stepfather Walter Grubbs, and the aunt and uncle who raised him, Martha A. (Palmrose) Wilson and Arthur J. Wilson, along with numerous other relatives from the Vallerga and Palmrose families.

He is survived by his daughter Barbara Ellen Brightman of Klamath, CA, grandson Trevor David and partner Steven of Northlake, TX, his stepdaughters and their husbands: Nancy Holmes McPartland (Charles), Jeannette Reinholtsen (Dennis), both of Eureka, CA, Renee Leppek (Chris) of Penn Valley, CA, and Franci McKown (Kirk) of Minden, NV. He is also survived by numerous cousins, nieces, nephews, step-grandchildren, and great-grandchildren.

Bob was a father, grandfather, great-grandfather and a friend to many. He will be missed. The family would like to thank the staff at Frye’s Care Home for their care and loving friendship with Bob over the past several years.

A graveside service with military honors will be held at Ocean View Cemetery, 2 p.m., Tuesday, September 24, 2024. In lieu of flowers, donations in his honor may be made to Hospice of Humboldt or a charity of your choice that supports the local community.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Bob Palmrose’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

BOOKED

Today: 11 felonies, 15 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: Two-Vehicle Collision Blocks Westbound Lane on State Route 162 North of Willits

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 26th, 2026 – Jason Esselman

RHBB: Highway 1 Still Fully Closed South of Elk as Crews Work Overnight on Landslide

Mad River Union: 8 weeks later

OBITUARY: Bobby Benton Dobbs, 1937-2024

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Aug. 29, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Bobby Benton Dobbs passed on June 29, 2024, in Eureka, at St. Joseph Hospital, surrounded by his family.

He was born on February 8, 1937, to Guy James Dobbs and Marie Verna McFall in Clovis, Fresno He was 87 years old.

He attended school until around the age of 16 and left with his brother (Jimmy) north to Sacramento and later Humboldt County working in construction. Later he joined the Northern California Laborers Union until he retired in 1992. During this time, he worked in many places, including Humboldt, Del Norte, and Trinity counties mostly on road construction and laying pipe. Then around 1979 he went south for work in Guerneville and Santa Rosa. Then to Pittsburg, Antioch, and Oakley to work in the refineries, always returning to Eureka during breaks in work.

After coming to Eureka, he met and married Leona Christensen and had two children — Donald and Kim. He later divorced and married Nancy Bolt and had one child Linda. Nancy had four previous children — Loretta, Dale, Larry, and Gary. They divorced and later he met and married Joan. She had four children of her own, Dana, Billy, Dale, and Lori. They divorced and while living in the Bay Area, he met and married Cheri she had two boys of her own, Joe and Kevin. Cheri and Dad moved to Merlin, Oregon, upon his retirement.

Besides working in construction, dad and his second wife Nancy owed Coogie’s Bar and Card room between 3rd and 4th on F street in Eureka. He and his third wife Joan ran the Driftwood on First Street in Eureka for a few years.

For those who remember my dad they will remember what a hard worker he was, as well as his love for gambling, drinking and raising hell. He also drove stock cars out at Redwood Acres in the 1960’s, Car 15.

While living in Oregon he raised pigs for the 4-H and had a pet cow named Debbie and several other animals. He loved his dogs (mostly miniature dachshunds) he had up to 12 at one time. It was like a stampede when someone came up the driveway. He had chickens and when the wild turkeys came around, he made sure there was food for them too. He loved animals. When they divorced, he moved back to Eureka in 2012.

He missed his animals so much, so when this little cat with big eyes walked into the office his daughter Kim worked at, she immediately took her to her dad. From that day on he would say, she was the best gift I ever gave him.

His grandson Robert moved from Sacramento and was staying with him until finding his own place. They remained living together which was great company for them both. The last year of his life his dementia and age got the best of him. I appreciate that Robert was there with him during this time so that he was able to remain at home.

Bobby was preceded in death by his parents Guy and Marie Dobbs, his brothers Gordon and James and Sister MaryLee. He is survived by his son Donald Dobbs (Virginia) of Eureka, daughter Kim Gunderson (Dave) of McKinleyville, and daughter Linda Banfill (Ray) of Lakeport Ca. Six grandchildren Steven (Sage) of Redding, Robert, Leona of Eureka, Randy of Boise ID, Trenten and Cory of Dallas Tx. He also had six great grandchildren Carter, Frankie, Nico, and Grant of Boise Id, Alex and Elizabeth of Eureka.

I am sure my dad would have loved a big party in celebration of his life, but I am sure he was happy that all his children and some grandchildren gathered to celebrate his life.

Thank you to Aryes Family Cremation for your kindness and work. His final stop and resting area with be at Greenview Cemetery in Arcata, with his brother Gordon.

His family would like to thank the wonderful staff of St. Joseph Hospital. The nursing staff was amazing and a special thank you to Dr. Segiura, who took his time to explain and listen to me about my father. Thank you to kitchen, housekeeping, and security staff for all the special thing you do.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Bobby Dobbs’ loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

DUI Checkpoint at Undisclosed Location in Eureka Tonight! Don’t Be Dumb and Drive While Under the Influence!

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2024 @ 3:23 p.m. / Crime

Press release from the Eureka Police Department:

On August 28, 2024, the Eureka Police Department will conduct a driving under the influence (DUI) Checkpoint from 6 p.m. to 2 a.m. at an undisclosed location.

DUI checkpoint locations are determined based on data showing incidents of impaired driving-related crashes. The primary purpose of DUI checkpoints are to promote public safety by taking suspected impaired drivers off the road.

“Impaired drivers put others on the road at significant risk,” Chief Brian Stephens said. “Any prevention measures that reduce the number of impaired drivers on our roads significantly improve traffic safety.”

Eureka Police Department reminds the public that impaired driving is not just from alcohol. Some prescription medications and over-the-counter drugs may interfere with driving. While medicinal and recreational marijuana are legal, driving under the influence of marijuana is illegal.

Drivers charged with a first-time DUI face an average of $13,500 in fines and penalties, as well as a suspended license.

Funding for this program was provided by a grant from the California Office of Traffic Safety, through the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Boise Fire Held at 12,907 Acres, 46 Percent Containment; Crews Aim to Strengthen Containment Lines on Eastern Flank

Isabella Vanderheiden / Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2024 @ 3:05 p.m. / Fire

###

Fire crews continue to make good progress on the Boise Fire, burning near Orleans along the Humboldt-Siskiyou county line. Last week’s wet weather helped fire crews take control of the blaze and strengthen containment lines along the fire’s perimeter.

As of Wednesday afternoon, the fire has held at approximately 12,907 acres and is 46 percent contained.

“There’s still some interior burning – mostly what we call heavy fuels – but there’s no active fire along the leading edge of what has already burned,” Bob Poole, a spokesperson for California Team 11, told the Outpost. “That rain we had on the fire [on Friday night] brought in quite a bit of moisture – I think an inch to an inch-and-a-half – and that helped us quite a bit. It slowed down the fire and allowed us to insert troops to improve those fire lines.”

Crews are focusing fire suppression on the eastern flank of the fire, which is burning in steep, “almost inaccessible” terrain along Granite Creek in Siskiyou County.

“This kind of terrain is unforgiving,” Poole said. “We’re trying to get troops in there now, so we put in a couple of spike camps, which is mostly where the hotshot crews we’ll be inserted. There, they will be closer to the fire line so they don’t have to travel two hours in, two hours out every day and they can spend more time working on the fire.”

Asked about containment on the east side of the fire, Poole said incident management would not establish firm containment lines “until we’re confident that it will hold.”

“We don’t want to call it contained until we’re positive that that hand line will hold,” he continued. “That area is so steep, we could have something running at the top of the hill … that would roll down the hill and pass the containment line and ignite something at the bottom of the hill.”

Evacuations are still in effect for residents surrounding the fire, even on the western edge where containment lines are already established. Incident management is hoping to get folks back into their homes as soon as possible, but many of the roads in the fire area are inaccessible due to downed trees.

“One of our projects right now is to clear those interior roads of downed trees and rocks to make them passable again,” Poole said. “There are quite a few areas right now, primarily on the western side, where there may not be a threat of fire, but there’s literally no access and it’s still a very dangerous area. There are a lot of standing dead trees in that area and it doesn’t take much for them to just fall over.”

The following additional information comes from the Six Rivers National Forest:

Boise Fire Quick Facts:

- Acres: 12,907

- Crews: 17

- Containment: 46%

- Engines: 32

- Detection Date: August 9, 2024

- Dozers: 1

- Cause: Under investigation

- Helicopters: 10 + 1 UAS

- Total resources: 783

- Fixed wing: available as needed

Headlines

• Traffic control remains in place along the Salmon River Road between Butler Flat and Nordheimer Flat for the safety of firefighters and residents. Expect up to 30-minute delays. Incident personnel driving vehicles with more than two axels will not be allowed on the road.

• Fire information phone: (707) 572-4860 or email at 2024.Boise@firenet.gov

• Get all your Boise Fire information in one mobile-friendly place! See link here.

• Evacuations are in place for residents near the fire area in Humboldt County. For the most current evacuation information please visit the Boise Fire linktree or visit:

✓ Humboldt County: Link.

✓ Siskiyou County: Link.

Leader’s Intent

The Boise Fire is being managed with a full suppression strategy.

Operational Update

On the fire’s western edge, crews continue to mop up and secure existing containment lines. Hazardous trees are being felled along interior roadways. Improvements continue to be made to the indirect dozer lines. Two spike camps are being utilized near the fire’s edge to decrease firefighters’ travel time. Where feasible, suppression repair and road system improvements have started. Firefighters will be backhauling hose, equipment, and other unnecessary items in areas where they are no longer needed.

Weather and Fire Behavior

High pressure will remain over the region this week. Temperatures may be above average for this time of year. As the vegetation dries out from the recent rains, more smoke may be visible from heavier fuels. During peak heat hours, upslope 8 mph winds are expected on the southern and western aspects, with gusts at 10-15mph. Under current conditions, additional fire spread is not likely.

Harbor District to Consider Issuing Permit to Allow Repair (Rebuild?) of a Fallen Billboard in Humboldt Bay Tidelands

Ryan Burns / Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2024 @ 1:53 p.m. / Local Government

UPDATE: The Board of Commissioners voted 3-0 to require an initial study under CEQA.

###

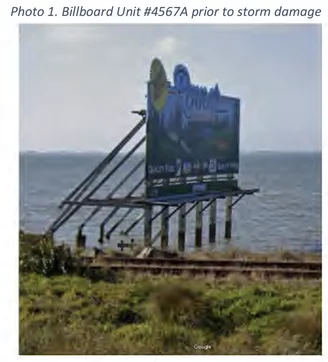

A billboard damaged in January storms sits face-down in Humboldt Bay. | Image courtesy Humboldt Waterkeeper.

###

At a special meeting this evening, the Humboldt Bay Harbor District’s Board of Commissioners will consider issuing a permit to re-erect a billboard that was damaged during January storms and has been lying face-down in Humboldt Bay’s tidal mudflats for months.

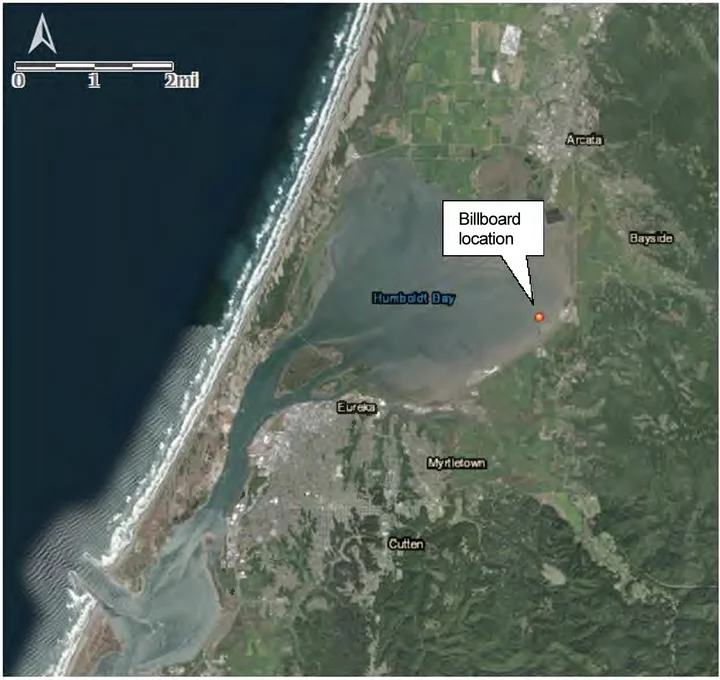

The sign in question, located on the west side of Hwy. 101 directly across from Indianola Boulevard, never received a permit. It was first erected in 1961, a dozen years before the Harbor District was created, and it stands (or rather stood) on land currently owned by the County of Humboldt.

Harbor District staff says the “repair project,” which would involve replacement of the damaged uprights and pile-driving a dozen new posts into the ground, qualifies for an exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) because the new structure would be located on the same site and have the same purpose and capacity as the one being replaced.

Rob Holmlund, the Harbor District’s director of development, told the Outpost via email that there doesn’t appear to be any relevant, official distinction between the terms “repair” and “rebuild,” but regardless, the sign has effectively been grandfathered in. “From the Harbor District’s perspective, the billboard is ‘legal non-conforming,’” he said.

If approved, the permit would allow the sign’s owner, outdoor advertising behemoth OutFront Media, to continue operation of the billboard for another five years, after which it would be removed, according to a staff report.

Location of the proposed billboard repair. | Image via Harbor District.

###

But environmental advocates and governmental agencies are urging the Harbor District to deny the permit, citing potential impacts to the sensitive environmental habitat, the scenic view and the Humboldt Bay Trail, which remains under the last phase of construction to connect the cities of Arcata and Eureka.

In a letter to the Harbor District, the California Department of Fish and Wildlife noted that the sign is located in sensitive and ecologically important wetland habitats.

“Placement of a billboard in this location is not consistent with the ecological functions and values of these habitats and can include short- and long-term impacts to native plants, shore bird roosting, and potentially increased erosion potential of the marsh,” the agency’s letter states.

Furthermore, the site is being considered for a marsh restoration project associated with sea-level rise resiliency.

The state agency recommends that the Harbor District “take this opportunity to phase out a land use activity that is not consistent with ecosystem functions of the site” by denying the permit.

Jennifer Kalt, executive director of the environmental nonprofit Humboldt Waterkeeper, agrees with that recommendation.

“The Harbor District was created by the voters in 1973 to protect the bay and public trust wetlands for the benefit of all of us,” she said. “Rebuilding this billboard in the wetlands is contrary to protecting the environment, the scenic views we all enjoy, and the use of the Bay Trail that we’ve worked toward for decades.”

Humboldt County Public Works Director Tom Mattson said his department’s main concerns revolve around the active trail construction project.

“We want to make sure that they’re completely aware of the coordination that would be required if they get all the [necessary] permits,” he said.

That remains a big “if.” This morning, Mattson sent the Harbor District a letter noting that, from the county’s perspective, this project would qualify as construction of a new sign, and as such a county building permit would be required, complete with engineering plans demonstrating that the design conforms to stat building code.

The letter also notes that the applicant proposes to access the billboard site via “railroad tracks,” but the rails and ties in the area have been removed and the county’s construction project is taking place right there. And once construction is finished, the public will be traveling along that route.

The applicant — Allpoints Signs owner Geoff Wills, on behalf of OutFront Media — would also need to obtain a coastal development permit or exemption from the California Coastal Commission.

“We have yet to receive such an application,” Coastal Commission Public Information Officer Joshua Smith told the Outpost via email. “We issued an emergency permit to repair the billboard earlier this year. However, that was before the structure completely fell into the bay.”

The proposed reconstruction of the billboard would involve an excavator using driving a dozen six-by-12-inch lumber posts 10 feet deep into the ground. Vertical support posts (also six-by-12) and horizontal stringers would hold up the half-inch plywood sign, with wooden catwalks and braces built below.

The Humboldt Bay Harbor District will meet at 6 p.m., following a closed session hearing, at the Woodley Island Marina Meeting Room, 601 Startare Drive, Eureka, CA 95501.

Members of the public can attend the meeting in person or watch it on Zoom at the following link: https://us02web.zoom.us/j/6917934402

Meeting ID: 691 793 4402

One tap mobile (669) 900-9128, 6917934402#

Image courtesy Humboldt Waterkeeper.

As of Today, the Klamath River is Flowing Free for the First Time in More Than a Century

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2024 @ 12:07 p.m. / News

File photo: Mid-Klamath Watershed Council.

A banner day. More than 20 years after the Klamath Fish Kill — or the most well known of the Klamath fish kills — and after seemingly endless rounds of negotiations and politicking and lawsuits, the Klamath River today flows free.

It has been the largest dam removal project in American history.

Press release from a coalition of tribal entities and non-profit organizations (see list below):

Today, the last coffer dams were broken at the former Iron Gate and Copco No. 1 Dam sites, returning the Klamath river to its natural path and marking an end to a significant construction phase in the largest salmon restoration project in U.S. history. The project is a major step toward healing a critical watershed for West Coast salmon production and is widely recognized as a Tribal justice initiative that will help revitalize the culture and economies of several Tribal Nations whose homelands are in the Klamath Basin.

“I am excited to be in the restoration phase of the Klamath River. Restoring hundreds of miles of spawning grounds and improving water quality will help support the return of our salmon, a healthy, sustainable food source for several Tribal Nations. This is truly a great day for the Karuk and all the Native People of the Klamath Basin,” said Russell ‘Buster’ Attebery, Chairman of the Karuk Tribe.

“Another wall fell today. The dams that have divided the basin are now gone and the river is free. Our sacred duty to our children, our ancestors, and for ourselves, is to take care of the river, and today’s events represent a fulfillment of that obligation,” said Yurok Tribe Vice Chairman Frankie Myers.

Four dams have been under deconstruction on the Klamath river, which traverses the California-Oregon border, over the past year. Benefits of dam removal include reintroducing salmon to more than 400 miles of historical habitat, eliminating reservoirs that hosted massive blooms of toxic blue green algae each summer, and eliminating conditions that enabled fish diseases to thrive. All of these benefits are expected to support the rebound of what was once the third largest salmon fishery in the lower 48 states.

“While there is still work to be done, today we are celebrating,” said Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation, the non-profit entity tasked with the removal of the dams. “Watching the Klamath River return to its historic path in the reservoirs and now through the dam sites has been incredible, and I feel honored to take this project over the finish line for our Tribal partners, and river communities.”

Although the construction phase of dam removal is expected to be completed by the end of September (some remaining riverside infrastructure is still being deconstructed), restoration of the land along the river and in key tributaries that were previously covered by the reservoirs will continue for several years. Resource Environmental Solutions (RES), the company contracted to oversee the restoration, is committed to remaining active in the basin until vegetation is successfully established and the newly restored habitat is on a positive ecological trajectory.

Signed by: Klamath River Renewal Corporation • Karuk Tribe • Yurok Tribe • American Rivers • American Whitewater • California Trout • Environmental Protection Information Center • Institute for Fisheries Resources • International Rivers • Native Fish Society • Northern California Council, Fly Fishers International • Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations • Ridges to Riffles Indigenous Conservation Group • Salmon River Restoration Council • Save California Salmon • Sustainable Northwest Trout Unlimited

Background

Discussions about the potential for Klamath River dam removal began in earnest more than 20 years ago, shortly after an estimated 70,000 adult salmon died in the lower river before they could spawn. The 2002 fish kill was a traumatic event for Klamath River Tribal communities. In response, Tribal members started a grassroots campaign with the goal of removing the lower four Klamath River dams as a requisite step toward restoring the watershed to health. The Bring the Salmon Home campaign called on the company that previously owned the dams, PacifiCorp, to surrender the lower four Klamath River dams for the purpose of removal.

After years of protests, lawsuits, and direct action, PacifiCorp, the States of California and Oregon, Tribal governments, conservation groups, commercial and recreational fishing organizations, and local governments reached a settlement agreement in 2016 to remove the dams. It took additional negotiations to secure final approval from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) for the dam removal and restoration to proceed. FERC approved the license surrender order in November 2022, allowing the transfer of the hydropower project to the Klamath River Renewal Corporation so they could proceed with the removal.

The smallest of the four dams, Copco No. 2, was removed in 2023. The reservoirs behind the three remaining dams were drained in January of this year, carefully timed to minimize impacts on fish runs. The river has been returned to its historic path at each dam site. As of today, the Klamath River flows freely and will allow fish passage from the mouth of the river in California up to where it originates below Lake Euwana, just below Upper Klamath Lake in Oregon. Dam removal also opens access to hundreds of miles of high-quality tributaries for migrating salmon, steelhead, and other aquatic species.

More information about this historic dam removal and larger watershed-wide restoration effort is available at reconnectklamath.org and klamathrenewal.org

Quotes from Supporting Organizations

“The Klamath River was once the third largest salmon producing river in the continental U.S., and restoring its once-abundant salmon runs has been a priority for the coastal salmon fishing families that PCFFA represents for at least four decades. With the freeing of the river for salmon to once again fully occupy it, the valuable salmon runs from the Klamath are expected to more than double in numbers – which means more salmon fishing jobs and stronger coastal salmon fishing-dependent communities as an enduring legacy of these efforts. I am proud to have been a major part of making this happen.”

-Glen Spain, NW Regional Director, Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (PCFFA)

“Because of Klamath River dam removal, salmon can return to the Upper Klamath Basin in Oregon for the first time in over 100 years. This will help restore salmon runs for Tribes up and down the river, including the Klamath Tribes in Oregon. Sustainable Northwest is proud to have played a role in this Tribally-led project to restore salmon runs and healthy river flows, and support Tribal justice.”

-Lee Rahr, Vice President of Programs, Sustainable Northwest

“Big things happen when committed people decide that failure is not an option. So today, on behalf of Klamath River salmon and steelhead and the communities that cannot live without them, we celebrate all the talented, relentless people who wouldn’t take no for an answer – the people who lit the fire, the people who worked behind the scenes, the public servants who did the right thing – all of the people who got it done when everyone said it wasn’t possible.”

-Brian J. Johnson, Senior Policy Advisor, Western Water and Climate, Trout Unlimited

“I’m proud that CalTrout has been at the table pushing for this crucial and pivotal river restoration project to transpire, and it is so satisfying to share the experience with partners from fellow conservation organizations, government agencies, and most especially our Indigenous and tribal partners,” said Curtis Knight, Executive Director of California Trout. “Dam removal on the Klamath River is special not just because of its magnitude and impact, but because of all the people that came together to make this happen. We started this journey 24 years ago sitting at a negotiation table. Together this amazing community of committed people are pulling off the largest dam removal and restoration project in U.S. history.”

-Curtis Knight, Executive Director, California Trout

“When we remove a dam, we don’t just restore a river, we heal communities. This tremendous milestone is thanks to the ongoing leadership of the river’s Tribes and grassroots advocates, and holds important lessons for other rivers nationwide. American Rivers named the Klamath as the River of the Year for 2024 because it proves that we can overcome seemingly insurmountable challenges and make incredible progress by working together. American Rivers is honored to continue our work advancing restoration and partnering with communities across the watershed.”

-Dr. Ann Willis, California Regional Director, American Rivers

“I am proud to say that the fly fishing community has been a part of this process for nearly 23 years, and that we joined many partners at the negotiating table who were focused on restoring the Klamath to its historical greatness. The river is now running free & in its historical channel. The fishery & river will now have a chance to begin the process of recovery. We are happy for the river, the fish, our negotiating partners, and the Tribal communities - The river people - whose lives are forever changed for the better. Never give up was our motto. It has worked.”

-Dr. Mark Rockwell, VP Conservation, Northern California Council, Fly Fishers International

“The Indigenous Peoples and Tribal Nations of the Klamath River have fought long and hard for the Klamath River to flow freely and begin recovering from colonization. Today’s final breach of the last dam on the river marks the beginning of a new era on the Klamath River during which Indigenous cultures can thrive alongside the many species and communities that are dependent upon the resilience of the Klamath River. We would not have reached this movement without the remarkable commitments of the Klamath Basin Indigenous Peoples and Tribal Nations and their many partners. We celebrate as a united Klamath Basin.”

-Amy Bowers Cordalis, Executive Director, Ridges to Riffles Indigenous Conservation Group

“Local families, especially native families on the Klamath River, fought for generations for this day. Many of us, and our kids, grew up in the movements for fishing rights and dam removal and many local people’s childhood memories include the toxic algae and fish kills. Now our children, grandchildren, and schools are planting seeds and engaging in dam removal and restoration. Youth are learning about the local successful movement for the environment and civil rights and how powerful they can be, and have hope for the future. We are so grateful we are able to celebrate this moment with our families, and that in the near future our youth will be able to enjoy salmon and a clean river instead of having to fight so hard.”

-Regina Chichizola, Save California Salmon

“Today marks a significant milestone in our commitment to restoring the health of the Klamath River ecosystem. The removal of the Klamath dams not only restores the natural flow of the river but also paves the way for the resurgence of the nearly extinct Klamath spring Chinook. Historically the largest run in the basin, the Klamath dams had blocked 90% of their habitat. Thanks to decades of advocacy protecting the Klamath’s last wild spring Chinook genetics, these heirs to the upper basin can finally return home.”

-Amber Jamieson, water advocacy director for Environmental Protection Information Center

“International Rivers stands in solidarity with the Klamath River Tribal communities who have championed the restoration of their ancestral waters and ways of life. This historic dam removal, improving access to over 400 miles of habitat, represents a shared victory for all who recognize nature as a living ecosystem to be cherished and protected. As the world watches the Klamath flow freely for the first time in over a century, we are witnessing a powerful example of what’s possible when we prioritize ecological integrity and respect Indigenous stewardship. This victory ripples far beyond the Klamath, offering hope and inspiration for river defenders worldwide.”

-Isabella Winkler and Josh Klemm, Co-Directors, International Rivers

“The removal of the Klamath River dams marks a historic moment not only for the river and the wild, native fish that rely on it, but also for the countless individuals, Tribes, community members, and organizations who have worked tirelessly for this celebrated outcome. This achievement is a testament to the power of collaboration and perseverance, as together we have made a lasting impact on the future of wild fish that will benefit generations to come. Native Fish Society is honored to join in celebrating of this incredible journey, and to continue our mission of working towards wild abundance throughout the Pacific Northwest.”

- Mark Sherwood, Executive Direct, Native Fish Society

MAXIMUM ENFORCEMENT! The CHP Announces, Once Again, That It’s Not Going to Be Messing Around When it Comes to Drunk Driving This Labor Day Weekend

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 28, 2024 @ 11:18 a.m. / Crime

Press release from the California Highway Patrol:

As the Labor Day holiday approaches, the California Highway Patrol (CHP) is launching a statewide enforcement effort to keep the public safe on the road through the holiday weekend.

The CHP will initiate a statewide Maximum Enforcement Period (MEP) beginning at 6:01 p.m. on Friday, August 30, and continuing through 11:59 p.m. on Monday, September 2. During the holiday weekend, all available CHP officers will be on patrol to encourage safe driving and assist motorists.

“Everyone’s safety is our top priority, so make responsible choices. Drive sober, stay focused and help keep our roads safe for all who use them,” said CHP Commissioner Sean Duryee. “Your decisions behind the wheel can save lives – yours and others.”

During last year’s Labor Day MEP, 38 people were killed in crashes throughout the state. Of note, nearly half of the vehicle occupants who were killed in a crash within CHP jurisdiction were not wearing a seat belt. In addition, CHP officers statewide made 1,064 arrests for driving under the influence during the 78-hour holiday enforcement period.

Remember to keep yourself and others safe by designating a sober driver or using public transit. If you see a driver who seems impaired, call 9-1-1 right away. Be prepared to give the dispatcher details about the vehicle, including license plate number, location and direction of travel. Your call could save a life.

The mission of the CHP is to provide the highest level of Safety, Service, and Security.