Ultra-Endurance Cyclist Lael Wilcox Passes Through Humboldt on Record-Setting Journey Around the Globe

Isabella Vanderheiden / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 4:40 p.m. / This Kicks Ass

Lael Wilcox riding south from Bellingham, Wash. Image via Instagram.

###

Ultra-endurance bicycle racer Lael Wilcox is passing through Humboldt County today on her journey to become the fastest woman to circumnavigate the globe via bicycle.

At the end of May, Wilcox set off from Chicago on a monumental mission to cycle 18,000 miles around the world in just 110 days, aiming to break the current Guinness World Record held by Scottish cyclist Jenny Graham, who completed the feat in 124 days, 10 hours and 50 minutes. As of this writing, Wilcox has biked over 15,500 miles.

“I want to invite people living near the route to ride with me,” Wilcox wrote on her website. “I’m not just riding through places but also people’s lives.”

The Outpost contacted Wilcox via email to learn more about her journey but, as you can imagine, she’s a little preoccupied. We’ll update this post if we hear back.

You can track Wilcox’s progress in real-time at this link. It looks like she just passed through Eureka.

BOOKED

Yesterday: 9 felonies, 10 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: CHP Details Dramatic Water Rescue After Pickup Swept into Tomki Creek

RHBB: Minivan Over the Embankment After Semi Collision North of Leggett Amid High Water

RHBB: Heavy Rain Pushes Rivers Toward Flood Stage, Roads Impacted Across Northwest California

RHBB: Vehicle Reported Upside Down in Creek After Crash on Tompkins Hill Road

Eureka Breaks 27-Year-Old Rainfall Record After ‘Rare’ Late Summer Storm

Isabella Vanderheiden / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 12:08 p.m. / How ‘Bout That Weather

How ‘bout that rain, eh?

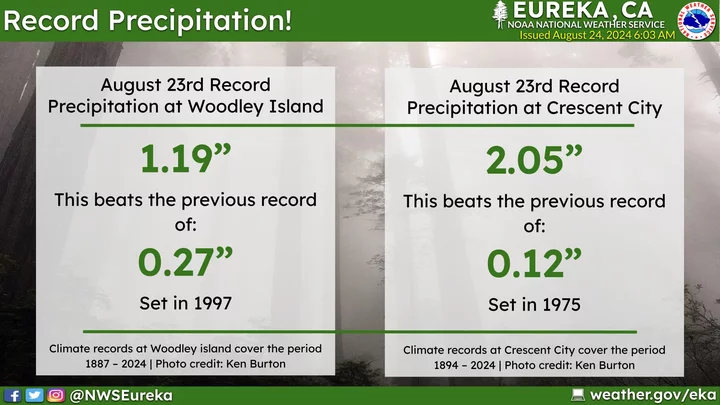

Yesterday’s “almost winter-like” weather broke rainfall records here on the North Coast. Our friends at the National Weather Service’s Woodley Island office say Aug. 23, 2024, was the wettest Aug. 23 ever recorded in Eureka and Crescent City.

Image: National Weather Service Eureka

As it turns out, this whole month has been wetter than usual.

“The normal precipitation for the whole month of August is usually around .18 inches here at Woodley Island. So far this month, we’ve gotten 1.34 inches,” NWS meteorologist Johnathon White told the Outpost this morning. “It’s not unheard of to have a winter storm come in this early, but it’s definitely not normal. Looking back at other records that were broken in August, we found about six other days where we received about an inch or more.”

Still, it’s pretty rare to get this much rain so early in the season, which doesn’t usually start until late September or October.

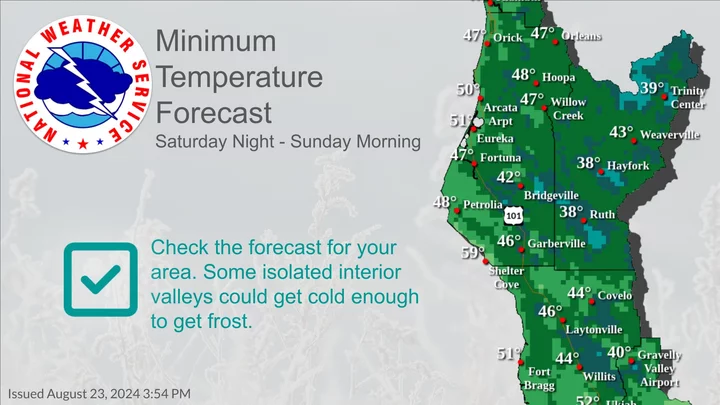

We can expect “summery-type” weather for the rest of the month, White said. Temperatures are expected to drop in some interior areas this evening, but the rest of the weekend and next week should be mostly sunny. Get out there and enjoy that sunshine while you still can, Humboldt!

###

Image: National Weather Service Eureka

THE ECONEWS REPORT: How to Think About Fire (From a Fire Expert)

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Wildfires

are burning across many parts of California, including in Humboldt

County.* Fires are complicated. Fire is somewhat paradoxical. It is

both a natural phenomenon and necessary for forest health, yet some

large fires are unnatural. The way to reduce big bad fires may be

more, smaller fires.

Complicated things are difficult to understand and even harder to discuss well in public. Luckily, the EcoNews Report has Lenya Quinn-Davidson, Director of the University of California Agricultural and Natural Resource’s Fire Network, who is both thoughtful and a good communicator about fire. Listen in and up your fire knowledge!

Are you a property owner and interested in returning fire to your land? Check out calpba.org/ to find your local prescribed burn association or check out the Fire Network to learn more!

*Note, this interview occurred on Friday August 16th and our discussion of the Boise Fire and other fires in California reflect the fire conditions as they existed on that day.

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: He Turned Humboldt County Into the ‘Holland of America’ With His Flower Farms … Until the Business Went Bankrupt (100 Years Ago)

Glen Nash / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 7:58 a.m. / History

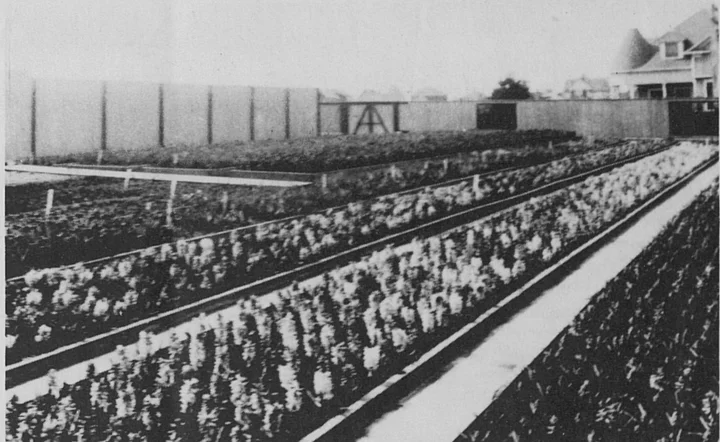

Charles Willis Ward’s residence and experimental garden, 2301 C St., Eureka. Photos via the Humboldt Historian.

The story of the establishment of the Cottage Gardens Nurseries in Humboldt County reads like a romance, one where things first happen by accident but all turns out well for all concerned in the end.

In 1888 Charles Willis Ward, a New York businessman, was ordered by his physicians to close his business in the city and seek “pure fresh air and quiet and rest of a country life.” He was a sufferer from nervous prostration, an ailment common to those bearing the heavy responsibilities of the business world.

Ward closed his office to seek a life in the open, close to nature. He camped during the summer in Northern Michigan; winters, he camped in Mississippi and, briefly, in Florida. He spent a few years pursuing this life but eventually settled in East Moriches, Long Island. He soon tired of having nothing to do, so he built a small hothouse and started growing many beautiful plants, mostly carnations. It was a hobby at first, but in due time his interest was so aroused that he entered into the business of “nursery man.” He purchased a large farm near Queens, Long Island, which proved to be the very beginning of the Cottage Nurseries. His initial venture proved very successful and in 1915, it ranked as the leading nursery in the United States.

In April 1913 he was summoned to Eureka to contest important legal proceedings affecting redwood timbered lands of the David Ward estate (of which he was part owner). He was quite ill at the time but managed the westward trip. By the time he arrived in Eureka, he was a very sick man. However, the climate of Humboldt County worked wonders and within 10 days he had a strong desire to go to work. Within another 10 days, he was hard at work in a garden. He so enjoyed Eureka, and Humboldt County in general, that he remained for over a year.

In January 1915 he made a business trip to New Orleans. While there he became sick and his return to Eureka was delayed for two months. Though he lost a lot of his strength, within four days after his return to Eureka he began to recover and, in a few days, he was back at work.

Rows of hyacinth line the “experimental garden” in the backyard of Ward’s C Street house.

He decided to make Eureka his home and soon made considerable investments there and elsewhere in the county. His first step was to buy a block of ground on C Street where he erected a large home (this home, located at 2301 C St., is still standing). His business operations came under the heading “Ward-Perkins-Gill Co., Inc.,” with Ward serving as president (the company also sold real estate). He built an experimental plant on the site to determine the possibilities of Humboldt County’s climate and soil. The results were very good. At the end of two years it became Cottage Gardens Nurseries, Inc.

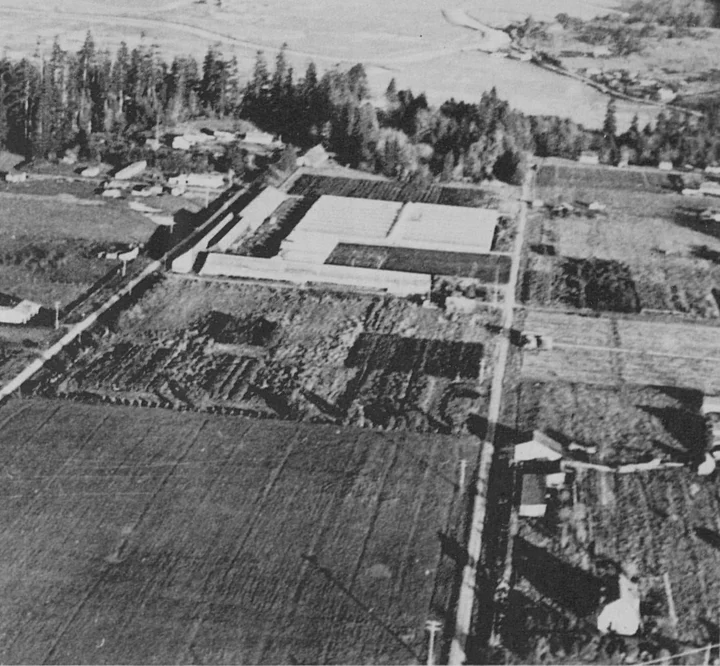

Bird’s-eye view of the Nursery’s Eden Tract (Eureka Slough in the background).

Ward added to this a 232-acre farm at

Carlotta and a commodious nursery in

the Eden Tract on Myrtle Avenue just

outside the Eureka city limits. This

“Garden of Eden” was bounded on the

west by Myrtle Avenue, on the north by

Trinity Street, on the east by Frank

Street and on the south by Pennsylvania

Street. Bela C. Wing and his son Cecil,

carpenters and builders, were in charge

of the construction of these buildings.

The millwork was done by the Cottrell

Moulding Mill, the acres of glass were

furnished by the D.C. McDonald Company (all local people).

The operations at Eden had electric lights, a steam plant, its own water works, several automobiles, tractors and other equipment. Ward later installed overhead sprinklers over the garden area which saved a great deal of labor.

In 1916 the Cottage Gardens Nursery at Eden near Eureka was considered a show place. The plant cost $80,000 to construct and covered 81 acres (all of which were either under glass, slats or cultivation). The great slat houses covered tens of thousands of Indian azaleas and carnations. Thousands of baby trees had a snug, warm home under acres of glass. Rows and rows of rhododendrons, roses, broad-leaved and coniferous evergreen and ornamental shrubs stood in never-ending variety. Some plants were imported, others were native to the area.

The experiments carried on by Ward proved that evergreens, along with other plants and bulbs, could be grown in Humboldt County and sold on the open market in competition with Japanese growers. He met with railroad and steamship magnates to secure an equitable freight rate to the Atlantic and mid-West points to sell his goods. He finally won.

Ward demonstrated that the climate and soil of Humboldt County was ideal for growing hyacinths, narcissus, tulips and other bulb flowers. Through his efforts, Humboldt County became known throughout the nation as the “Holland of America.”

Indian azaleas were just one of the many flowering shrubs which flourished under Charles Willis Ward’s care.

The propagating department had the capacity of 3 million plants per annum and a selling capacity of $150,000 per annum. The list of stock for sale included 50,000 azalea indica; 50,000 rhododendrons; 25,000 berried hollies; 10,000 Irish yews; 10,000 umbrella palms; 10,000 fancy Japanese evergreens; 25,000 broadleafed evergreens; 200,000 various coniferous evergreens; 50,000 florist special forcing plants; 100,000 heathers; and 150,000 roses.

It was largely through the efforts of Ward that the first annual sweet pea carnival was held in Eureka. During the three-day celebration, the Cottage Gardens gave away millions of sweet peas, along with instructions on how to grow them. Humboldt County remains great sweet pea country.

The Cottage Gardens Nurseries employed hundreds of local people over the years and taught them how to graft different plants and how to grow and take care of them in general. During summer school vacations many students worked there. There are many of these former employees still living here.

In the beginning, a Mr. Van Abelis was the superintendent of the Eureka branch of Cottage Gardens Nurseries. In 1918 Konrad Weirup served as manager of the many acres under glass. Another employee, Ronald Kausen, was in charge of the office accounts for 43 years and also traveled around the country selling the nursery plants and produce. Otto Kausen served as general manager of the nursery until his retirement in 1963. His brother, Ronald Kausen, then became manager until 1969 when John Wahlund took over.

One of my relatives had a steady job hauling redwood leaf-mould to the nursery. He had an agreement with the McKay Lumber Company which allowed him to go into its timberland and rake up leaf-mould, a natural food which rhododendrons thrive in, from under the old redwood trees. This man was kept busy for many years hauling tons of leaf-mould to the nursery.

In the early 1920s, my mother got a job at the Cottage Gardens Nurseries where she learned to transplant begonias, gloxinias and graft many other plants; she became an expert at this. She transplanted all of the very small eucalyptus trees which were eventually planted along the northwest side of 101 Highway between Eureka and Arcata (this highway was built in the early 1920s). Every time I drive past those trees, I think of them as a monument to my dear mother, Jessie M. Nash.

During years 1914-15, a McKinleyville branch of the Cottage Gardens was started, with roughly 520 acres located on Central Avenue and Sutter Road; this section was devoted to raising assorted bulbs. Ward purchased this land, then overgrown with trees and brush, from Jason Wagoner. The land was cleared by Cecil Carr and his sons, using gas farm tractors and one team of horses. This process consisted of felling the trees, then dynamiting the stumps. The horses or tractors would then pull out the stumps, which were then sometimes burned. The McKinleyville branch was managed by a Dutchman, Von Alse, and later by Vanden Volch.

In 1917 Ward published a catalog, California Grown Holland Bulbs, which described the many types of bulbs grown on the Pacific Coast and included beautiful pictures of their flowers along with prices and instructions on how to grow them. One bulb, the new Giant White Trumpet Narcissus Imperator (a daffodil), sold for $200 each! Ward ordered tens of thousands of Dutch, French and Japanese bulbs to be grown at his McKinleyville branch.

Cottage Gardens Nurseries, Inc. owned a 232-acre ranch in the beautiful valley of Yager Creek, extending from the highway far up into the most attractive valley in the county. When Ward purchased this land it had recently been logged over and was covered with giant redwood stumps. These were removed and the land leveled, ploughed and planted in alfalfa and corn. More than 1,000 assorted fruit and nut trees were planted.

A model dairy ranch was established at this Carlotta ranch and was stocked with a herd of thoroughbred registered Jerseys, some of which were selected from Dr. Rae Felt’s herd. A model dairy barn was built with concrete floors, a water system, electric lights, swinging stanchions, manure carriers and all the latest known appliances. These beautiful ranch buildings are still there for all to see as they head east down the hill leaving Hydesville.

Rumor had it he would play music his cows at the Carlotta ranch to help them give more milk. This practice is still being carried out today by many dairy ranchers who have found it to be practical.

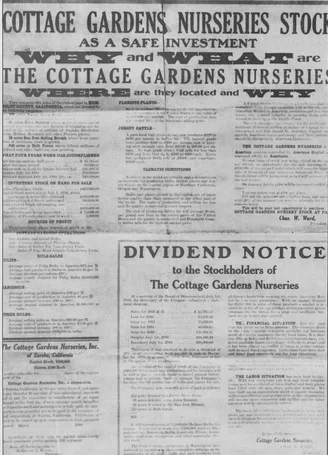

In July 1918, Ward advertised capital stock for sale at $100 each. He said, “Liberty Bonds, War Saving Stamps sales, and Red Cross contributions have rendered available funds exceedingly difficult to secure and it has been almost impossible at times to secure enough cash to meet fixed expenses. Collections have been slow and for many good customers ask for long extensions.” He went to explain in the advertisement how many of the best young men had been drafted or had enlisted in the armed services and how the “book value” of Cottage Garden stock was well above par and stockholders were advised not to part with their holdings.

In 1922 Cottage Gardens Nurseries, Inc. started having some difficulty in making its payroll. For several months Konrad Weirup put up the money to make the payroll, a sign that the nursery business was slowly going downhill. Weirup was repaid by receiving the acres in bulbs at McKinleyville. Charles Willis Ward finally went broke in Humboldt County, and Cottage Gardens Nurseries fell into the hands of the receivers.

Ward had been a millionaire, but was convinced the sky was the limit. A brilliant and affectionate man, he had wonderful dreams for Humboldt County and everything he did was for the betterment of the area.

Ward raised one son, David Ward, and four daughters. Little is known about his wife, other than she was Jewish and never came to live with him in Humboldt County. David finally bought back Cottage Gardens Nurseries and soon leased it out. In 1925 David lived at 2333 E St., Eureka.

The nursery was sold in the early 1970s to the Westbrook Bulb Farms of Smith River in Del Norte County. Robert D. Herrick served as manager of the Cottage Gardens Nurseries until 1985 when it was closed and the land sold off to various developers and builders. This beautiful land, once filled with flowers, has been built over with streets and houses.

Charles Willis Ward lived in Eureka until his death. Ward loved Humboldt County and gave much to promote it around the world. Many beautiful plants and trees now stand as monuments to his hard work and commitment.

In 1915 Ward wrote a book, Humboldt County: The Land of Unrivaled Undeveloped Natural Resources, on the Westernmost Rim of the American Continent. In it he promoted the climate of this county and gave this entire county a real boost. He was far ahead of the times.

Some 22,000 acres of fine redwood timberland, bordering the Klamath River on the south for a distance of 17 miles, was owned primarily by the Ward Estate, along with some smaller parcels. This land was put on the market and Ward proposed that the U.S. Government purchase it for a national redwood park. His suggestion is today a reality.

One Sunday in February 1989, my wife and I went for a ride to see the new houses built in the Eden Tract and to see just what was left of the old Cottage Gardens Nurseries. We arrived just in time to snap a picture of the last remaining building (the beautiful old office) being torn down and demolished.

The end of a man’s dream …

Top: Cottage Gardens Nurseries’ Eden Tract office building during the 1920s; Below, Glen Nash happened to drive by as it was being demolished in February 1989.

###

The story above is from the November-December 1992 issue of the Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society. It is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

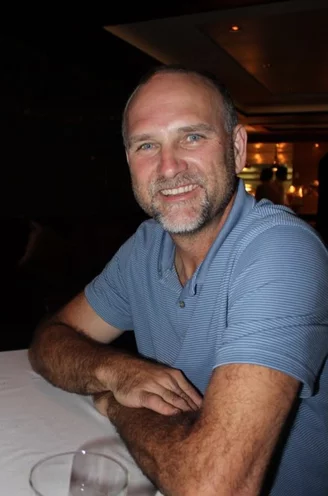

OBITUARY: Mark Alan Whitman, 1953-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Mark Alan Whitman, son of Ethen Miles

Whitman and Carolyn Bylerly Whitman,

passed away August 10, 2024, at his home in

Burnt Ranch at the age of 71. Mark was

born in Spokane, Washington on January

20, 1953.

He was preceded in death by his parents and his sister Karis Marie Yerton. He is survived by his first wife, Adrienne Whitman of Eureka, and their two daughters Rienne Marzo Bilz (Brian) of Zell, Germany, and Yarrow Zella Whitman (Eric) of Austin, Texas; his second wife, Lezley Troxell of Arcata, and their daughter Zoe Troxell Whitman (Jack) of Manhattan, N.Y.; and his beloved partner Anna McKee of Shady Cove, Oregon. Mark is also survived by his sister Connie Heine (James) of Delano, Minn., his brother Lee Whitman (Lavelle) of Blue Lake, and his sister Mary Holt of Sacramento, and numerous nieces and nephews.

After attending grade school in Malin, Oregon where he had a paper route, the family moved to Hoopa, where he worked for the Young Adult Conservation Corp in1970. He graduated from Hoopa High in 1971. After high school he worked at a veneer mill in Orleans, a summer on fire crew in Salyer, on his uncle’s farm in Washington, as a car mechanic in Eureka, at McKnights Ready Mix in Willow Creek and as a car mechanic in Sausalito, before opening F Street Garage in Arcata with his brother-in-law Richard Yerton. F Street Garage specialized in repair of imported cars and was very successful for 12 years.

After closing F Street Garage he bought a shop in Blue Lake and utilized his skills as a welder and metal fabricator to open Blue lake Iron Works. His commitment to community led to many situations in Blue Lake where he volunteered his time and expertise (or his forklift ) to help complete a project.

For being a “small guy,” Mark Whitman was actually a giant of a man. His energy often “filled the room.” His presence could not be ignored, and you could always count on him to keep a lively conversation going. Mark was exceptionally skilled, brilliant, funny, curious and the most helpful person a friend (or stranger) could ever ask for. He embraced fully every experience and encounter he had, and was always seeking opportunities to acquire new knowledge and expertise and to share it. As far as problem solving, and fixing anything or even having just the right tool (even if it meant making it) he was worlds above the rest of us. He had great passion for creative artistic expression, both for himself but also encouraging others to do the same. His unique approach to life and his varied experiences gave him a very fascinating (and thought provoking) philosophical perspective of the world, as well as his hopes and dreams.

Mark spent many years creating a sustainable homestead on his property in Burnt Ranch. It is his desire that this homestead will continue as a haven and and as a “learning center” of sorts for homesteaders, for do-it yourselfers, for upcyclers, for artists, for lovers of the earth. Anyone lucky enough to get close to Mark and his points of view or to be a recipient of his generosity and problem solving skills will never forget them (or him). He will be greatly missed by many.

A celebration of life is being planned for all who knew him. The celebration will be on Saturday March 22, 2025 at 2 p.m. in Blue Lake. It will begin with gathering of souls in front of his shop at 620 Railroad Avenue followed by a serenaded walk to the Mad River Grange at 110 H St, for ceremony, tributes, food and story telling then continuing to the Logger Bar at 510 Railroad Ave for music, libations and more sharing memories of an unforgettable giant of a man.

“Death is not bad, just sad” (a quote by Mark Whitman).

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Mark Whitman’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

OBITUARY: Donald James Smith, 1952-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Donald James Smith, born on January 22, 1952, in Healdsburg, passed away peacefully at home on June 30, 2024, surrounded by his loving family, after a courageous battle with cancer.

Don, or DeDon as he was often called, was known for his unique dry sense of humor and his love of practical jokes. He enjoyed fishing the rivers, camping, and was a devoted Dodgers fan as well as a Giants fan after his son began his career in San Francisco. An animal lover, Don always had a dog by his side, including his Irish Setter, Prince, and his beloved little Gigi, who was with him until the very end.

After retiring from the Louisiana Pacific Pulp Mill, Don found great joy in caring for his grandkids, nieces, and nephews. He was a truly dedicated father to Joshua and Remie. He could often be found tinkering in his garage or hanging out in his man cave. Don had a passion for unique vehicles, whether it was an Austin Healey, a Ranchero, a Bobcat, or a Volkswagen van. He also supported his wife, Lorraine, with their horses, helping at horse camp, towing trailers, mucking stalls, and feeding the animals.

Don’s love for motorcycles, especially Harley-Davidsons, led him to become a member of the Cruising Clowns Motorcycle Club, where his playful personality fit right in. He also enjoyed spending time at the casinos.

When Don was a senior at Arcata High School, he met the love of his life, best friend, and soul mate, Lorraine. They were introduced by a mutual family friend on Chester Street in Arcata, and from that moment on, they were inseparable. Together, they raised Joshua and Remie, always quiet but always there for those in need. Don’s love for Lorraine was unparalleled, and he cared deeply for her until the very end. Even in his final days, Don’s main concern was ensuring that Lorraine would be taken care of. On June 14, while in the hospital, they celebrated their 51st wedding anniversary.

Don is survived by his wife, Lorraine; son, Joshua (wife, Carly); daughter, Remie (husband, Jonah); and grandchildren, Sawyer, James, and Rosemary. He is also survived by his mother, Mary Jane; brother, John; nephews Nathan and Adam; all his Zerlang family; and his good friend, Jim. He was preceded in death by his father, Jim, who was honored by having Jim Smith Lane named after him, as well as his sister, Connie, who passed away at a young age, and his grandmother, Nonnie, whom Don helped care for in Cloverdale.

Don took great pride in his work at the mill and in driving down Jim Smith Lane, dedicated in memory of his father. He attended all family gatherings, where it was important to him that hamburgers were served — no onions, no tomatoes, and ketchup only.

The family invites everyone to a “Farewell Don” party at the Zerlang family cabin, 1369 Fay St., Samoa, on Sunday, September 1st, from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. Hamburgers will be served — no onions, no tomatoes and ketchup only.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Don Smith’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.

OBITUARY: Mark Edward Hudson, 1964-2024

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 24, 2024 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Mark

Edward Hudson

January

21, 1964 - August 11, 2024

With

great sadness, we announce Mark’s passing on August 11, 2024, at the

age of 60 from a heart attack. Mark was born on January 21, 1964, to

Charles and Linda Hudson in San Francisco, and moved to Fortuna with

his family at the age of two,

Mark

was tall, dark, and handsome with the most beautiful blue eyes. He

attended Fortuna Elementary schools and graduated from Fortuna Union

High School in 1982. He was a standout athlete in both basketball and

baseball. He was one hell of a pitcher!

Mark

was employed by Johnny’s Cookhouse and Crown Redwood in high school

and then worked for 21 years at Eel River Sawmills, Inc.

Mark

met his high school sweetheart, Wendy, in April 1982, and he finally

married that girl in 1988. He leaves behind three beautiful children

who were his world. Kyle Joseph was born in 1989, Ryan Matthew in

1991, and his beautiful daughter MacKenzie Marie in 1997. He was the

best hands-on dad ever. Mark loved his family so much and cherished

being called “Pop Pop” by his grandchildren. He truly was

the best!

Mark

loved coaching all the kids in their sports and never missed a game.

He was everyone’s dad, uncle, son, brother and the best friend you

could ever ask for. He was a lifelong Raiders fan, loved a good BBQ,

enjoyed playing cornhole, bingo, and his vacations to Mexico were

medicine for his soul. Nothing made him happier than watching the

grandkids run around the yard. Family time was truly the most

important thing to him.

Mark

is survived by his mom and stepfather, Linda and Kent Wrede of

Fortuna; his siblings Matt and his wife Merle Hudson and their family

of Hydesville; Bonnie Hudson and her sons Jake and Tyler Hines and

their families of Fortuna; and his twin half-sisters Sandee and

Shawnee.

Mark

leaves behind his wife Wendy of 36 years; his children Kyle and

Danielle Hudson of Fortuna, Ryan and Chelsea Hudson of Carlotta, and

Kenzie Hudson and Chad Watson of Fortuna; and his beloved dog Sydney

Marie. His handsome grandsons Maddox Nolan, Jace Ryan, and Jax Kyle

of Fortuna, and his beautiful granddaughters Sawyer Grace, Avery

Hope, and Logan Lynn of Carlotta, will forever cherish his memory. He

also leaves behind his cousins Laurie, Greg, and Judy and their

families. Additionally, he is survived by all of Wendy’s family, of

which there are many, and he was the best uncle to all of his nieces

and nephews. We would also like to include the many friends that

became family throughout his life and a very special person in Mark’s

life, Robin.

Mark

was preceded in death by his grandparents, his father Charles Hudson,

his baby granddaughter Maverick Hudson, his favorite bingo buddy, his

mother-in-law Shirley Wyatt, his sister-in-law Shirley Stevens, and

many more relatives and close friends who passed before him.

We

are eternally grateful for the outpouring of love and support shown

to our family during this most difficult time.

We will honor Mark with a celebration of life on Saturday, September 21, 2024, at 2 p.m. at the Fortuna Veterans Memorial Building.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Mark Hudson’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here.