Much Fentanyl Discovered During Search of Sleepy Suspect’s Vehicle in Trinidad

LoCO Staff / Monday, Aug. 14, 2023 @ 11:46 a.m. / Crime

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On Aug. 9, 2023, at about 7:14 a.m., Humboldt County Sheriff’s deputies on patrol in Trinidad conducted a vehicle investigation on an occupied vehicle parked in the area of Scenic Drive and Cher-Ae Lane. The occupant of the vehicle, 42-year-old Kathlene Crystal Mellon, was found to be asleep in the driver’s seat with drug paraphernalia in plain view.

Deputies woke Mellon and conducted a search of her person and vehicle. During their search, deputies located approximately 7.3 ounces of suspected fentanyl, over 3 grams of methamphetamine, drug paraphernalia and pepper spray.

Mellon was arrested and booked into the Humboldt County Correctional Facility on charges of possession of a controlled substance for sales (HS 11351), possession of a controlled substance (HS 11377(a)), possession of drug paraphernalia (HS 11364(a)), felon in possession of tear gas (PC 22810(a)) and committing a crime while released from custody on a felony (PC 12022.1(b)).

On August 13, while in custody at the Humboldt County Correctional Facility, Mellon was involved in a physical altercation with another inmate. Due to this incident, Mellon received additional charges of assault (PC 240) and battery (PC 242).

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

BOOKED

Today: 11 felonies, 15 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Today

CHP REPORTS

0 Snow Camp Rd (HM office): Car Fire

5980 Mm101 N Men 59.80 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

Cedar Flat (RD office): Trfc Collision-No Inj

3750 - 11631 Hoaglin Rd (HM office): Car Fire

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: School Bus Smoking on Highway 299 Near Snow Camp Road Prompts Fire Response, Snarls Traffic

RHBB: Vehicle Fully Engulfed in Flames on Hoaglin Road Near Trinity County Line

RHBB: Two-Vehicle Collision Blocks Westbound Lane on State Route 162 North of Willits

KINS’s Talk Shop: Talkshop February 26th, 2026 – Jason Esselman

Felony Warrant Suspect Arrested in Blue Lake

LoCO Staff / Monday, Aug. 14, 2023 @ 11:25 a.m. / Crime

Press release from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On Aug. 11, 2023, at about 3:26 a.m., Humboldt County Sheriff’s deputies conducted a vehicle investigation on a vehicle parked at a business on the 700 block of Casino Way in Blue Lake. The vehicle was observed to be occupied by two people, one of whom was identified as wanted felony warrant suspect Mikeala Leejune Smith, age 24.

Smith was detained and a search of her person and the vehicle was conducted incident to arrest. While searching, deputies located 25 grams of fentanyl, approximately .54 grams of methamphetamine and drug paraphernalia.

Smith was arrested and booked into the Humboldt County Correctional Facility on charges of possession of a controlled substance (HS 11350 and HS 11377(a)) and possession of a controlled substance paraphernalia (HS 11364), in addition to warrant charges of robbery (PC 211), grand theft (PC 487(a)), theft of property (PC 484(a)), committing a felony with a prior serious felony conviction (PC 667(B)-(I)) and shoplifting (PC 459.5).

The second occupant of the vehicle was detained and released at the scene.

Anyone with information about this case or related criminal activity is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

GROWING OLD UNGRACEFULLY: Letter to Scott

Barry Evans / Sunday, Aug. 13, 2023 @ 7 a.m. / Growing Old Ungracefully

FWIW: Going through some old papers last week, I stumbled on this. Seven months into what turned out to be a nearly two-year sabbatical 23 years ago, it’s my response to an email from my buddy Scott, poet and fellow-meditator, who “hoped that in traveling, I would discover a way to ease my pain.” After bristling about this for awhile, I replied:

Hey, Scott!

You write of my pain. I don’t know about all this pain you assign to me: pain’s pain. Nothing special. I certainly don’t think it’s useful to “do” anything about it, like traveling the world. Where did we ever get the idea that we need to discover anything?

Most of our friends and family don’t seem to understand what this year (or more…at least 14 months, anyway, since our home is rented out until the end of this year minimum) is about for us. We barely know ourselves, but I know I feel more alive here in Tbilisi [Georgia] (I would have said the same for Guanajuato, Patmos, Mount Sinai, Nablus, Trabzon [Turkey]…when we were in those places) than I felt in Palo Alto before we left. I love life unrolling like a scroll. We literally don’t know where we’ll be from one day to the next. We decided to go to Patmos [Greece] on a whim (finding a cheap one-way London to Athens flight on the web and the next ferry from Piraeus happened to go to Patmos); we took the bus from Jerusalem to Eilat on an hour’s notice, arriving in Sinai at night, hitched the only vehicle on the road at 10 pm and were deposited at the sweetest place for the night-ah, trust!; we flew to Antalya [Turkey] on a day’s notice, once again exhausted with Israel; we came to Georgia because an Austrian woman had raved about it in Oaxaca [Mexico], and we discovered a Georgian consulate in Trabzon…and here we are, in an apartment, so lucky.

I seem to love the unexpected, life unfolding. Most of my life I’ve lived with a sense of purpose. Now “purpose” seems too confining: when I have a purpose, I set a goal, and move towards that place down the road…easily blinkered to the flowers and pitfalls off to the side. Now in my unrealistically ideal world, there are no distractions, nothing is more important than anything else. Yeah well, that, as I say, is the ideal. In fact, I check our stocks more often than I’m willing to admit. I fret when we end up paying more than $12 a night for a room. (Hey, we’re on a budget, alright?!) Traffic drives me crazy. I drive me crazy. But that’s not the point. The point is that, dammit, we upped and we went (with one bag apiece). Not quite knowing why, except that it would be different. Scott, this is what I want you to know: I’m so freaking grateful: (1) that we were in a financial position where we could take off for a year-plus (as long as we stick to our $40-50/day budget) and (2) that we did. Everyday, something new, a new encounter, a new awareness (often about our relationship—imagine that, after 26 years!), an adventure. This isn’t like I used to travel: I used to think traveling was sightseeing. Now I think it’s listening.

Pain? I’ll give you pain:

- The Palestinian engineer we were in a minibus with, we’d been having this courteous, fact-filled conversation about the Israel-Palestine situation, about the daily restrictions and humiliations the Palestinians have to endure, and I ask one more question, I forget what, and he loses it, suddenly shouting, says something like, “I’ll tell you why. It’s because we’re all so fucking miserable living like caged animals, that’s why!” Suddenly I get it.

- Rebecca, our Mexican landlady and confidante, telling the story of her marriage: her husband, like many Mexican husbands, took up with a younger woman, moved out, then he invited Rebecca to join them—as their maid. She says something in Spanish which I don’t understand, but with Louisa’s help I get as something like, “In your dreams, buster!”

- Notari, father of a family from Abkhazeti, breakaway province of Georgia, he and his family fled the fighting there nine years ago, came to Tbilisi as refugees with two young kids, lost everything, got their lives going again, still very poor, he and his wife (they’re both professors) haven’t been paid in six months. The daughter got a grant from Soros Foundation and spent last year in Georgia (State!)…she’s translating his toast to the time when they can entertain us in their old home: and I sense they know he’s pissing in the wind. They’ll never go home. They give us their khanzi, drinking horn, to remember them by.

Tblisi: Dinner with family from Abkhazeti, Louisa taking a swig of something potent from the khanzi. (Barry Evans)

It’s not all like that, of course. But someone said, “Tell me your pain so I can know you,” and we’ve gotten to know a lot of people the past seven months. You?

Love, Barry

THE ECONEWS REPORT: Sonoma Proposal for Eel River Dams, and Why Humboldt Should Be Wary

The EcoNews Report / Saturday, Aug. 12, 2023 @ 10 a.m. / Environment

Cape Horn Dam at Van Arsdale Reservoir. Photo: PG&E.

On this week’s episode of the EcoNews Report our host Tom Wheeler is joined by Alicia Hamann and Craig Tucker from Friends of the Eel River to discuss a vague, last-minute proposal from water users to take over part of the Potter Valley Project. Pacific Gas and Electric, owners of the two Eel River dams and diversion tunnel that make up the Project, are in the midst of preparing their license surrender and decommissioning plan. The company will submit a draft plan this November, with a final plan due January of 2025.

And PG&E has been clear that they want to rid themselves of this aging, liability-ridden project - they’ve told stakeholders that their plan will call for removal of all infrastructure in the water. But: They also told stakeholders this spring that the company would be open to proposals to take over all or part of the project through the end of July.

Well, a proposal from Sonoma Water, Mendocino County Inland Water and Power Commission, and the Round Valley Indian Tribes was published just last week, but it’s really more of a plan to make a plan. While it supports removal of Scott Dam, the plan is unclear about the future of Cape Horn Dam, or how any of their proposed modifications to Cape Horn Dam will be financed. Leaving the most difficult questions unanswered makes it all but certain that this proposal would delay PG&E’s plans for decommissioning and dam removal.

Tune in to learn about what Eel River advocates think about this proposal, and how conservation organizations plan to continue holding PG&E to a swift timeline for dam removal.

Links

Past episodes about Eel River Dams

- What’s Next for Eel River Dams, 2/12/2022

- The Beginning of the End for Eel River Dams, 4/16/2022

- Big Doings on the Beautiful Eel River, 8/6/2022

- PG&E Finally Taking Dam Safety Seriously, 4/1/2023

HUMBOLDT HISTORY: Trains of Pack Mules Run By Famous Muleteers Opened Up the Humboldt Interior for Mining and Settlement

Andrew Genzoli / Saturday, Aug. 12, 2023 @ 7:30 a.m. / History

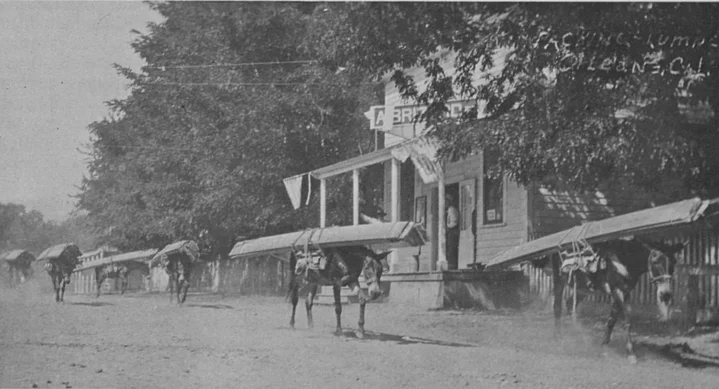

After a long, hard trip from Blue Lake and Korbel, this pack train arrive« at Orleans with its cargo. Strung-out along the road, they walk independently and at a steady pace. This photo and the one below were taken in 1920. Photos via Humboldt Historian. Click to enlarge.

When the miners had depleted the lowlands, the easy-to-get-to gold claims, they pushed on through the forests, into deep canyons. They climbed the rocky mountains to find streams running white with rapids — always in the hope that here may be a new bonanza. As the miners moved, they left behind them the easier, faster methods of transportation. No longer could they go by locomotives, stagecoaches, wagons. At times it was almost impossible for four-footed animals. It was necessary for supplies and machinery to be carried into the mining country, where settlements cropped up almost overnight with population numbers running into the hundreds. Like magic, rumors of gold drew masses of humanity.

The pack train became an indispensable necessity, linking the mines with civilization and the source of supply. In some of the more isolated localities, the arrival of a pack train was an event of importance. The mule pack train can be given a major portion of credit for the early-day development of Humboldt’s interior, the country of northern and northeastern Humboldt County.

A. Brizard’s famous pack train shared in this growth. Besides serving the branch stores in the mining country, the pack trains carried freight — pipe, machinery, supplies — for the mines. It was reported, as the packing season came to an end, Brizard pack trains had carried a half-million pounds. Brizard was not alone in packing, for there were numerous operators serving the countryside.

This picture shows how needed lumber was brought into communities on the back of mules. They pass the A. Brizard store at Orleans.

According to Hutching’s California Magazine, December 1856, “There are generally forty to fifty mules in a train, mostly Mexican, each of which will carry from three hundred to three hundred and fifty pounds, and with which they will travel from twenty-five to thirty-five miles per day, without becoming weary.”

In Humboldt, the mileage accomplished was shorter, because of the mountainous country. The mule trains passed over some of California’s ruggedest terrain to reach their destinations.

Hutching’s said:

If there is plenty of grass they seldom get anything else to eat. When fed on barley, which is generally about three months of the year, November, December and January, it is only given once a day, and in proportions from seven to eight pounds per mule. They seldom drink more than once a day, in the warmest weather. The average life of a mule is about sixteen years.

The Mexican mules are tougher and stronger than American mules; for, while the latter seldom can carry more than from two hundred to two hundred and fifty pounds, the former can carry three hundred and fifty pounds with greater ease.

It was not possible to carry food in the freight train, enroute. At night at the end of the run, the mules were turned loose to graze along the trail.

In 1865, when Alexander Brizard and James A.C. Van Rossum purchased the firm of William Codington & Company, Codington was in the forwarding business. From this point it may be assumed the Brizard firm added a pack train service to the mines of the Klamath-Trinity area.

A notice in The Humboldt Times dated May 26, 1865 states: “Particular attention paid to Forwarding Goods to any part of the Mines. All orders will be filled with care and will receive prompt attention at the old stand of Wm. Codington and Company.” This store was located at the corner of Ninth and G Streets, and was occupied by the new owners. A corral was located just west of the store.

Mules are found listed in the Humboldt County assessment rolls for 1867 as being owned by A. Brizard. “There is something very pleasing and picturesque in the sight of a large pack train of mules quietly descending a hill, as each one intelligently examines the trail, and moves carefully, step by step, on a steep and dangerous declivity, as though he suspected danger to himself, or injury to the pack committed to his care,” said an eye-witness account in Hutching’s magazine. In Northern California, there were at least five thousand mules engaged in packing in 1856. The number was to grow as population and commerce increased.

Oscar Lord in the Humboldt County Historical Society yearbook for 1954, wrote:

The early settlers of Northern Humboldt, Klamath and Siskiyou Counties were supplied with provisions, furniture, and gold mining equipment brought in by pack trains. These trains usually consisted of from 30 to 40 mules, each carrying an average of 300 pounds. A bell-mare led the pack train. There was also a mule for each packer. The crew consisted of a boss packer, a packer for each 10 mules, and the bell-boy who doubled as cook, led the kitchen mule. During the trip the men subsisted on pancake bread, bacon and beans. “The three large trains operating in this area in the 1880’s were owned by Alexander Brizard, who had 125 mules; Thomas Bair, who had 60 mules; and William Lord, who had 75 mules.

Pack train routes, as Mr. Lord remembered them, were described in these words:

One of the old trails taken by the pack trains into the Orleans Bar country started at Arcata, then went to Trinidad, and northeasterly over the mountains by Redwood Creek near the homestead of the Hower’s, which was a stopping place for many years; then up the Bald Hills; through the Hooker ranch to French Camp; down into Martin’s Ferry; to Weitchpec and Orleans Bar. Another trail, which was used more than the trail by Trinidad, commenced a short distance east of Glendale; to Liscom’s Hill; down into the North Fork of Mad River; to Fawn and Elk Prairies; down into Redwood Creek at Beaver’s; to Hower’s, through the Hooker Ranch, etc., as noted above. A loaded pack train took seven days to travel the 78 miles from Arcata to Orleans. The return trip without a load took only five days.

Here, the Martin’s Ferry is occupied, crossing the Klamath River with a string of pack mules headed for the interior. The photo was by the girl photographers A. and Z. Pitt of Martin’s Ferry whose cameras saved a treasure of valuable history.

On the first page of the Arcata Union, Vol. 2, No. 1, July 30,1887, one finds A. Brizard advertising at the “Stone Store, Arcata,” with branch stores: Orleans, Willow Creek, Weitchpec, in Humboldt; Somes Bar, in Siskiyou Co., Francis and White Rock, New River in Trinity County.

Attention is called to packing:

Running my pack trains to above points, am prepared to furnish transportation to these or any points in the mountains on favorable terms. Goods consigned to me for transportation will be stored free in my fireproof building.

For many years the A. Brizard pack trains were loaded in corrals in town. Then the train was taken out of town about a mile on the Alliance Road, where time was taken to readjust the packs for the remainder of the trip.

Before the advent of the Arcata & Mad River railroad, freight was carried from Arcata to mountain destinations. Later freight was to be loaded aboard the trains. This cut down the distance considerably and saved the strength of the mules for the mountainous work.

According to a note found in the Blue Lake Advocate, dated April 18, 1891, this was the time when the new loading location came into use. Mrs. Eugene F. Fountain, Blue Lake historian, included this in her “The Story of Blue Lake” on October 6, 1955.

Mr. Brizard’s train under the management of J. Zeigler left Blue Lake Wednesday morning for Somes Bar, with a cargo for Martin’s Ferry, Orleans Bar and Somes’ Bar. This is the first train which left this spring and after this all of Mr. Brizard’s pack trains will start from Blue Lake.

Mrs. Fountain reported in a story she found in the Blue Lake Advocate, July 27, 1895, the fact the pack trains often returned with “pay-loads.” Sometimes they made special supply trips:

Every year A. Brizard’s pack trains make a few trips to Etna, Siskiyou County, where they pack a whole lot of flour from the mill there, to supply his stores at Somes Bar, Orleans, Francis and White Rock. The two trains in charge of Ed Scott and Weitchpec Ben, respectively, are expecting to go to the Etna mill in a few days. Mr. Brizard usually buys every year about 45,000 pounds of flour from that place.

When the Blue Lake Advocate celebrated its jubilee May 7, 1938, a story from the files for December 26, 1903 is featured: “THE PACKING SEASON OVER.”

The packing season from Blue Lake to different points in northern and northeastern Humboldt is now closed for the winter, A. Brizard’s train under the charge of Oscar Brown, has gone to winter quarters at Bald Mountain, while the other train, under Ed Scott, is making its last trip to Hoopa and Weitchpec. The faithful mules will be turned out for their winter vacation on Brizard’s Bald Mountain ranch, and in about two or three months packing operations will be resumed. Ed Scott, one of the best boss packers in Humboldt County, has decided to quit the business and from now on he expects to be employed for the Orleans Bar Gold Mining Co., at Orleans. Ed put in a good season last year, having been on the road and trail since February 15th, but he considers this kind of life as a little too hard for him, and hence his resignation.

At the end of the next season, February 20, 1904, the Advocate said:

Brizard’s pack mules, some seventy-seven in number, were driven from Hoopa to Bald Mountain, Saturday, for a change of pasture. Some thirty-three head, in charge of Domingo Bibancos, the old Chilean packer, were taken to Arcata Monday for a week’s stay, where they will be fed hay. The packing season will commence some time next month.

Mrs. Fountain wrote the mules were being loaded behind the A. Brizard store at Blue Lake. At times there were unavoidable mishaps such as this:

When leaving the freight yard with a load of shovels, one of the faithful mules turned its back too close to a window in the store building and as a result the long shovel handles passed through a pane of glass. The loss was charged to that particular mule’s credit with a little remonstrance on the side.

Here are some of the packers who kept the mountain routes and commerce alive. With the exception of Ben Billie of Weitchpec, upper left, they came from Mexico and South America. Not in the photo is Domingo Bibancos, probably one of the most famous of packers in northwestern California.

Besides Domingo Bibancos, another South American packer, was Sacramento Moreno. In 1881, in an advertisement, Brizard recognized his association, as the “Brizard & Moreno pack train.” This association remained until 1887, when Moreno sold his interest to Brizard. Moreno was in Arcata in 1873, when in March of that year, Edmond Le Conte sold the packer property in Arcata for $450.

Alexander Brizard was convinced he had the best pack trains, the best packers, and he did not hesitate to say so. In a letter on June 8, 1896, to J.T. Parsons of San Francisco, an official in the Red Camp Mining Company, Brizard wrote:

As to the transportation your company requires will say this is my line and flatter myself that I can handle in more satisfactory manner than anyone else in this section. Trust I need not refer you to anyone for my reliability and facilities to carry out any engagement. I refer to this for there are some with only a few mules who will offer to take all that is offered them, and do the work where and when they can or convenient.

I deliver goods beyond Cedar Flat and could not if the other route you mention is used. The goods then must go by rail to Redding thence to Weaver by team, 40 miles to North Fork of Trinity, by team about 20 miles, thence by pack mule to Cedar Flat, another 24 miles. It has to go through all these hands, each adding their charges. There is no regular pack train running between North Fork and Cedar Flat. You would have to have someone arrange terms for this additional transportation.

To show you advantages of my route, I will receive the goods f.o.b. Steamer Pomona from your city, marked ‘Diamond B’ Arcata, with added initial to desegregate from my freight. I will deliver to Cedar Flat, 2/4 cents per pound, provided of course packages are suitable for mule transportation.

His letter adds: “I have had 40 years experience in packing. Mined many years ago with a rocker at Cedar Flat.”

In another letter a few days later, Brizard told the San Francisco mining man: “It is six days from here to Cedar Flat — say eight days to be safe. If my pack trains are out, I can, if I know a few days in advance, arrange a train to pick up goods.”

On June 15, 1896, still writing to the Red Cap Mining Company officers, A. Brizard advised:

The mining pipe should be put up in 150-pound rolls not over, by 150 we can add here. Be sure not to forget the rivets, needed tools, as there is some distance to where these can be had, and in this there can be an expensive loss of time. It is the little things that are inexpensive, but are overlooked, nevertheless. Important to have indispensable good man to direct work on ground, and remind you that the most efficient helpers, good ordinary laborers, are not always available in those parts. I offer this as a suggestion.

Although there are many stories in existence of pack train mules owned by other operators, carrying five or six hundred pounds, A. Brizard, would never permit abuse or overloading of his animals. In an excerpt from a letter concerning shipment of mining equipment, Brizard said: “Will not agree to take freight till I see it, as I can’t tell what mill and pipe will be. Some think a mule can pack anything. I know they cannot.”

During this period of packing, tobacco was an important ingredient for both packer and miner. In a letter dated, October 8, 1896, A. Brizard wrote:

Yours of 3rd received. In regard to quantities of tobacco used. Some months use 300 pounds to 500 pounds according to business. I never order less than 150 pounds or 200 pounds at one time. ‘Battle Ax’ has been looking up and I now sell quite a quantity, and seems to be improving. Whenever ordering never send me less than a 100-pound lot of same.

You must understand my business, that at certain times of the year I handle large quantities of tobacco, according to the season. Some months four times as much as others. I have to pack all my goods by mules, so have to depend on the weather …

Buying of mules for the pack trains was a job A. Brizard himself undertook, which he so states in a letter to J.W. Stout of Klamath Falls, Oregon:

I have just returned from a trip to Round Valley where I purchased all of the mules that I required at a very low figure, as mules are plentiful there just now and can be had at any price. I do not know of anybody in this part of the country who you could make a sale to. I have on hand over 150 head, some of which I would be willing to sell very cheap …

There was always the weather to contend with, as A. Brizard indicates in this portion of a letter to W.J. Wiley, San Francisco, on May 10, 1896: “First day of decent weather. Had been raining, delayed pack trains. Two of mine delayed four days this side of Redwood Creek. Could not cross.”

Tired, pack animals and their loads arrive at Orleans. Knowing it was the end of the journey, some of the mules stretched out for a rest before unloading.

On September 13, 1896, the Arcata & Mad River passenger-train plunged through a suspension bridge over Mad River. The drop of 35-feet, killed seven passengers and injured many more. A. Brizard wrote in a letter to the Red Cap Mining Company he was both shocked and horrified by the tragedy. The victims, he knew, as friends and customers. Too, he pointed out, there would have to be some changes in getting freight to Blue Lake, since the train had been used carrying Brizard freight. This would now be delayed until the bridge was rebuilt. He announced he would immediately start moving freight, by wagon to Blue Lake. Apparently this was satisfactory with the mining people.

The A. Brizard pack trains carried all types of freight, merchandise for the branch stores. There were often interesting requests, such as this one by A.F. Risling, manager of the Orleans store on November 19, 1892: “… Send by train one large demijohn. Please have it filled with Greenwald whiskey and address Samuel Bell, and also one gallon for Charles Bristol. I should like to get up a gallon myself for a few personal friends for Christmas and assure you no harm will be done.” The word “harm” was given additional assurance with an underline.

Old-time packers knew how to overcome thirst, if whiskey was in the manifest. By driving horseshoe nails into the keg, then withdrawing it, they were able to encourage enough leakage to acquire the “needed spiritual” reinforcement, we are told. Ernest C. Marshall of the Bar Vee Ranch at Hoopa, viewed a picture on a calendar issued by A. Brizard, Inc. It showed a typical pack-train readying to leave Blue Lake. Two of the packers in the picture were Bell-Boy Bud Carpenter, and Ben Bille.

In reminiscing I cannot help but turn back the pages of time to my youthful years,” the old-time packer wrote in a letter to “My Children”, “when the scene was common and the only means of getting ware to the most remote areas in the mining regions …

The mule trains of that era consisted of from 25 to 50 mules, though at times on urgent orders two mule trains would merge, making the train capacity 75 to 100 mules. A crew for 25 miles consisted of around 3 men. There was a bell-boy, second packer and the boss packer, or foreman. The duties of the bell-boy included the culinary department. He requisitioned all food and utensils, with the boss packer’s approval, needed to prepare meals and make the lunches. He led or rode the bell-horse ahead of the pack train. It was impossible to leave a mule behind, once the bell-horse started forward on the trail.

The salary of the bell-boy was $30 per month, including found (‘found’ means board). The duty of the other packers were general; unloading the packs at the end of the day, unsaddling and feeding or pasturing the mules as they depended entirely on forage along the trail. Therefore, camps were always made where there was plenty of feed. They picketed the bell-horse and the mules never strayed very far away.

The day started long before dawn, with the bell-boy busy around the camp fire getting breakfast for the crew, while the other men brought in the mules to saddle and load for the day’s trek.

They left as soon after dawn as possible, traveling not more than 15 to 20 miles per day, to give the mules more rest and foraging time at the end of the day.

The second packer rode in the middle of the pack train to better watch the mules so they did not bunch up or shove another loaded mule off the narrow trails, and to see that the mules were riding straight up, because sometimes over the narrow trails a lop-sided load could throw a mule off the trail, killing the animal. The second packer’s pay was around $35 a month, with found. The boss packer rode behind the train, keeping an eye on all the mules. He was responsible for the care of the mule train and his men, and of the safe delivery of the cargo in his care. His salary ran around $40 to $45 per month, and found, depending on the number of mules in his train. He had to maintain all the equipment, keep the mules well shod, make arrangements for the feed of the animals along the route. He had to know the carrying capacity of each mule, which varied from 300 to 400 pounds. There were only a few mules that could carry a top pack, such as a cook stove or bulk loads weighing 300 pounds or more.

All loads were carefully packed and roped together at the starting point, or warehouse, and placed in strong burlap bags for side packs. These weighed from 150 to 200 pounds each making the loads for the mules from 300 to 400 pounds. The loads were placed in long rows, ready for the next day at dawn.

The life of a packer on a mule train was a rugged one. He had to be able physically to endure the cold weather, the rain, snow, sleet,and frost,and the terrible windstorms of the high mountains. Crossing swollen streams entailed the use of canoes, later swimming the mules across, to again load and resume the journey.

Regardless of the weather, the packers knew that for their protection from the weather they had to pitch their tent for the night. They also had to dry out their blankets as best they could under these weather conditions. Deep trenches had to be dug around the tent to prevent the water from running into it while the men slept. Bedding consisted only of blankets and canvas spread on the ground.

Each packer had a leather canteen for carrying his personal belongings, lunch and a leather blind that had to be used in the loading and unloading of the mules. The blind was placed over the eyes of the mule, and the end straps over the ears, holding it in place. Some of the mules were outlaws, never taming, regardless of heavy loads and work.

“You will note that the loads on the mules have two different hitches,” Mr. Marshall says, referring to the photograph. “The most generally used, the diamond hitch and barrel hitch. I had the occasion of participating in the loading out of the last pack train that was operated by A. Brizard, Inc. when I was employed by the company as a clerk at Hoopa. That was around the year 1920.”

Somewhere in Humboldt County there should be a bronze statue dedicated to the faithful pack mule-servant and slave.

When California’s first commercial oil was taken from the Mattole Valley, it was on the backs of pack mules to Leland Stanford at his San Francisco refinery. Wool was shipped from the Bald Hills to Humboldt Bay; from the mountains of south county to Shelter Cove, and from Blocksburg to the waiting steamer — all aboard pack mules.

There were butterfat trains from Bear River and the Mattole Valley for Port Kenyon and the San Francisco market — long trains working along the trails with many duties to accomplish in those worrisome times of settlement. The same trains brought settlers and their belongings. Without them — the pack trains — what would our history have been like?

The store at Weitchpec gets its cargo of necessities as the mule train arrives. Similar trains traveled to White Rock and other trading posts scattered throughout the inland area.

###

The story above was originally printed in the September-October 1982 issue of The Humboldt Historian, a journal of the Humboldt County Historical Society, and is reprinted here with permission. The Humboldt County Historical Society is a nonprofit organization devoted to archiving, preserving and sharing Humboldt County’s rich history. You can become a member and receive a year’s worth of new issues of The Humboldt Historian at this link.

OBITUARY: JoAnne Anita Scott, 1933-2023

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 12, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

JoAnne Anita Scott (January 18, 1933 – August 8, 2023) entered this

world 90 years ago in San Francisco, the eldest of four children born

to Anita Charles and Frank Murdock Sr. Her parents met in San

Francisco when her mother was in the city working and her father had

just arrived in S.F. after graduating from Haskell Indian Boarding

School in Kansas. JoAnne’s mother Anita was Yurok and her father

Frank was a member of the Sokaogon Chippewa Community of the Mole

Lake Band of Lake Superior Chippewa in Wisconsin. Maternal

grandparents were Susie Wauteck and Lagoon Charles, Paternal

grandparents were Mary Poler and William Murdock.

JoAnne passed away peacefully in her home and was preceded in death by her parents Anita and Frank Murdock Sr., her late husband Wallace Scott, Sr., children Judith Lorentzen, Pamela Myers, Laurence Whitlatch, sister Jean Stanshaw, grandchildren Christie Love Ferris, Garrick Scott, Rebecca McKinnon, Michelle Lorentzen, great-granddaughter Kepcenich Aubrey.

JoAnne is survived by her children Anita Scott, Mary Jo Peets (Larry), Kathy Ferris, Wallace Scott Jr., Wesley Scott Sr., siblings Susie Painter (Matthew), Frank Murdock Jr. (Marjorie), grandchildren Lillian Hostler, Laurence Myers, Kimberly Peets, Travis White, Jessica Fawn Canez, Stanley Ferris Jr., Joseph Ferris, Daniel McDonald Scott, Chvski Jones-Scott, Nantsvn Jones-Scott, Teexeeshe Scott, Haley Scott, Wesley Scott Jr., Nekichwey Scott, Tohtehl Scott, 24 great-grandchildren, 8 great-great-grandchildren.

JoAnne graduated from Eureka High School in 1951 and was given the recognition from her graduating class as being the most athletic female. She was a life-long lover of sports, especially softball which she continued to play into her 60’s with a senior citizen slow-pitch league.

JoAnne was involved in her various interests over the years – art classes, working every voting season for many years as a voting day polling volunteer, volunteered at the Legion Hall in Arcata and McKinleyville, was an active member for many years in the McKinleyville Moose Lodge - her portrait is hanging on the club wall to this day. She loved animals and some of her favorites was Molly the goat, Princess Ratina, Red Baron, Bruce Lee, generations of baby skunks that visited her back porch every year and even the neighbors’ two peacocks who would come visit her front porch regularly because they knew she would feed them grapes.

As a life-long learner who went back to school after most of her children were grown, JoAnne became a Registered Nurse and was able to attend the Nursing Program alongside her daughter Judy. In her retired years JoAnne went back to school again and graduated from Humboldt State University with a Bachelor of Arts degree in Native American Studies.

The family appreciates the kindness and care received from Dr. Antoinette Martinez and Sandra Trabue, Community Health Representative at United Indian Health Services, and her niece Darla Marshall for always taking the time to celebrate special days, shopping trips and other outings with her Auntie JoAnne.

Pallbearers: Frank Murdock III, Travis White, Stanley Ferris Jr., Joseph Ferris, Nantsvn Jones-Scott, Wesley Scott Jr., Teshy Scott, Cha’Keni White, Ch’Mook McCovey, Whi’Kil McCovey, Matthew “Pride” Painter Jr, Mathew Swanson, Lonnie Dean, Al Kenny Dean, Robert Woods, Bering-C Sienicki, Delmar Allen Jr., Laurance Myers.

Honorary Pallbearers: Frank Murdock Jr., Joseph Murdock, Matthew Painter Sr., Robert McGahuey, Emil Marshall, Lance Lorentzen.

Services will be held on August 15, 2023 at 11 a.m. at Paul’s Chapel in Arcata. JoAnne Scott will be laid to rest at the Trinidad Cemetery and reception will follow at the Trinidad Town Hall.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Joanne Scott’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Aiko Harada Uyeki, 1927-2023

LoCO Staff / Saturday, Aug. 12, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Aiko Harada Uyeki passed away at home in the early morning of July 6

at the age of 96. She was preceded in death by her beloved

husband of 71 years, Edwin, who died in October 2022. Despite her

diminutive size, she was tough and resilient, surviving childhood

hardships, two bouts of breast cancer and numerous challenges

throughout her life. She was a joy to the end, with a pure heart and

forgiving nature. She truly embodied her name, Aiko, “child of

love.”

Aiko was born in Seattle to Jingo and Shizue Harada in 1927, at the Northern Pacific Hotel where her father worked as a clerk. Her parents had immigrated from Kanazawa, Japan, on one of the last ships before the Asian Exclusion Act of 1924. Her family moved to Los Angeles when she was 5 years old. They lived in Boyle Heights until they were incarcerated in 1942 in the Arizona desert, a story paralleling 120,000 other Japanese and Japanese Americans living on the West Coast. After a year and a half, Aiko and her parents were able to leave the Gila River camp for Evanston, Illinois, where her father received sponsorship to work. Her brother, Roy, had already found employment in St. Louis. The boarding house where Aiko’s parents stayed did not allow children, and through a chance encounter on a bus, Aiko moved in with a family in Evanston, working as a “house girl” caring for 3 small children. She graduated from Evanston High and worked as a secretary at the University of Chicago, where she later graduated with a liberal arts degree. It was there that she met her lifelong love, Ed. They were inseparable for 72 years.

Aiko and Ed raised three children, Terry, Bill and Amy, moving from Chicago to Cleveland, eastern Washington and Kansas City following Ed’s career as a scientist and professor. Through the years, Aiko worked as a secretary, job-sharing several jobs with her close friend, Ann Nelson. Later, she became an ESL teacher, which combined her love of English with her empathy for second-language learners. After Ed’s retirement and 30 years in Kansas, Ed and Aiko chose to return to the West Coast, settling in McKinleyville, California, near daughter Amy and her family. Aiko was active as a volunteer at the Mad River Community Hospital gift shop for 20 years; was a member of the McKinleyville Women’s Civic Club; and wrote short stories and remembrances with the Silver Quills writing group. The Humboldt Unitarian Universalist Fellowship was a focal point for spiritual, social, and civic engagement for Aiko and Ed, longtime Unitarians.

Aiko and Ed were devoted and nurturing parents and grandparents to six grandchildren and to all their loved ones through the years, with recognition of – and tender attention paid to – each child’s interests and pursuits.

Like her mother before her, Aiko was a published writer, whose written words simply and succinctly touched and engaged her readers. In the 1980s, she wrote articles published in major newspapers about the Japanese American incarceration during WW2. Her writing made its way into The Sun, a literary magazine, where stories from her life focused on larger themes, such as poverty, being uprooted, and prejudice. Over the years she spoke out against injustices inflicted upon scapegoated communities within, at, and beyond American borders. With her daughter Amy, she edited a poetry book of her mother’s Japanese senryu poems and participated in an exhibit of 4 generations of artwork of her family. A senryu she wrote to her daughter Terry expressed an apt portrayal of how many saw Aiko:

Bamboo

woman, bowed

But

unbroken by life’s storms,

Now

she stands erect.

Aiko’s lasting legacy is the loving kindness she shared with those around her. Her ability to live life simply, but with meaning and concern for others, acts as our moral compass. A celebration of her life and that of her beloved husband, Ed, will take place on November 11, 1 – 3 PM, Azalea Hall, McKinleyville.

The family is grateful for the loving care provided by caregivers in their latter years. In lieu of flowers or gifts, contributions in our parents’ memory may be made to a fund for scholarships for Asian American first generation college students, the Uyeki Scholarship Fund [make check out to Humboldt Area Foundation, 363 Indianola Road, Bayside CA 95524, Uyeki Memorial in subject line, or online at this link.

Those who will miss Ed and Aiko may envision their final departure, the way they often left an event: Ed, in front in the vehicle, impatiently saying: “C’mon, Aik, let’s go!” And imagining the look of delight on his face as she joins him, finally!

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Aiko Uyeki’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

###

Aiko Uyeki, 92, was sent with her family to a Japanese-American internment camp during World War II. “Even at my young age I noticed, from reading in newspapers, that German-Americans and Italian Americas were not removed from the East Coast,” she said. “Being stripped of our material possessions was not nearly as traumatic as the loss of our dignity.” Photo by Andrew Goff in 2019 at the “Lights for Liberty” vigil in Fortuna.