OBITUARY: Richard (Alan) Burns, 1955-2023

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 2, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

It is with great sadness that we have to announce the passing of Richard Alan Burns (67) on June 6, 2023. He passed away peacefully, just as he wished, while watching TV and resting in bed at his daughter’s home in El Centro, CA.

Alan was born in Eureka on December 11, 1955, to Richard and Carmen Burns. Alan went to South Bay Elementary School and graduated high school in 1974 from Jacobs Junior High School. Here is where he met a group of kindred spirits who affectionately called themselves the “Alley Gang” — Jerry Alley, Orlan Larson, Phillip Sanchez, Paul McKnight, and the late Matias Salas, Don Thomas, Darrel Crocket, David Alley, Steven Burres and Jake Mosely.

Graduating from high school, he decided to join the forestry service as a firefighter. He had always been passionate about nature and the outdoors, and this seemed like the perfect way to combine his interests.

After that, Alan decided to embark on a journey across the western United States. He had always been fascinated by the natural beauty of this region and was eager to explore it firsthand. However, as much as he enjoyed his time on the road, he returned to Eureka with the passing of his mother.

For the next 30 years he worked as a commercial fisherman on various boats in Eureka and Coos Bay. For many of those years he worked beside his two brothers, Kenny and David. Among his peers, he was affectionately known as “Big Al.” He will forever live on in the hearts of the fishing community as a delightful jester whose quick wit and hilarious commentary brought laughter among the crew.

He never cared about conforming to society’s norms or pleasing others. Instead, he followed his heart and did what made him happy. His carefree lifestyle was something that many people admired, but few had the courage to emulate.

Alan may not have been perfect, but he definitely got one thing right: his unconditional love for his daughters, Valerie and Lacey. With the support of their patient mom, Nancy Nichols, Alan always made sure to show his love and pride for his girls in every way possible. Whether it was attending their school events, cheering them on at their sports games, or just sitting down with them for a family dinner, Alan never missed an opportunity to be there for his family.

Alan was a true nature lover. He loved exploring beaches, camping in the woods, and taking refreshing dips in rivers and lakes. Fishing was one of his favorite pastimes and he always kept a fishing pole handy. He loved the challenge of trying to catch a big fish, but he also appreciated the simple moments of just sitting and enjoying the scenery. He had a special bond with nature and was blessed with a green thumb. He and his close friend David Cooper spent countless years working together nurturing their greenery with passion and dedication.

Alan was a man of many passions. One of his favorite activities was taking his canoe out on the Humboldt Bay and seeing where it would take him. He was also a rock enthusiast. Every time he went outdoors, his eyes were always scanning the ground for that one-of-a-kind gem. He spent hours upon hours searching for the perfect rocks to add to his collection and was always happy to show off his latest finds. Another hobby of Alan’s was archaeology. He was an amateur but loved the thrill of unearthing old bottles and other relics from the past. He would often spend hours digging around the Eureka area, looking for hidden treasures. It was a way for him to connect with the past and feel a sense of excitement about what he might find.

Alan also loved traveling the open road in his beloved truck and seeing where it would take him. He had countless memories of road trips, camping trips, and spontaneous adventures. He loved the freedom and independence that came with being behind the wheel of his truck. Whether he was driving through the mountains or cruising along the coast, his adventurous soul always led the way. Sometimes he had a plan, but more often than not he just let the road guide him. And no matter where he ended up, he knew his truck would be there with him, ready for the next adventure.

Alan is preceded in death by his parents, incredible big brother Kenny Burns, favorite nephew Kenny Alan Burns and granddaughter Adaline Pritt. He is survived by his dedicated daughters, Valerie Pritt (husband Joshua) and Lacey Bresino (husband David), his caring siblings Linda Alora (husband Mike), David Burns (wife Kim), Patrick Burns (wife Rachel) and Sister-in-law Robin, his loving grandchildren Vivian, Rockwell, David Jr. and Fletcher and many nieces and nephews.

Memorial Service will be held Saturday, August 12th, 12pm at the Woman’s Club in Samoa.

BOOKED

Today: 5 felonies, 11 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 20

CHP REPORTS

24500 - 24599 Us101 (HM office): Traffic Hazard

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: City of Arcata Hosting ‘Water Rates Workshop’ February 25, April 15

The Atlantic: The Protein-Bar Delusion

The Atlantic: The Decline of Reading: The Orality Theory of Everything

Governor’s Office: Here’s how many medals Californians have brought home from Milano Cortina 2026 for Team USA

OBITUARY: Jean C Vanderklis, 1942-2023

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 2, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Mom was born April 2, 1942, to Bennie and Katie Merritt in Magnolia, North Carolina.

In the summer of 1958 while walking on Carolina Beach with her cousin, a hurricane was on its way. A very handsome Air Force military police officer told them they needed to get off the beach. Mom told her cousin that dad was the man of her dreams. She was going to marry him. They met again a few weeks later and they started dating. Mind you, mom was only 16 years old.

That was the beginning of her fairytale life. Soon after, they married on November 2, 1958. Dad then left the service and the two of them began their move to California. Here they were, newlyweds and a German Shepherd named Fury set out in a 1951 Dodge pickup for Arcata, California.

Mom had really never been out of North Carolina and they were up to the adventure. Once they arrived in Arcata they found out they were expecting their first child. November 2, 1959, was their first anniversary and the next day their daughter Debra was born. Soon to follow was Katherine and then Pete had arrived.

There she was, 3,000 miles from home with three babies and only 20 years old. Dad worked three jobs. He bucked hay, was a gas station attendant and was fortunate to work for the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Department. She was the wife of a resident deputy in Orick.

Mom never really had a job other than the most important one…. being MOM. After we grew she took some part-time jobs since we were not totally dependent on her.

Mom and Dad had a fantastic relationship. The words love, respect, patience and understanding were often used. In November they would have been together 65 years.

Mom will be leaving behind the love of her life, Piet Van Der Klis; daughter Debra Kamberg (Robert); daughter Katherine Boone; son Pete Vanderklis (Jan) and daughter Angie Kendrick (Bobby); her grandchildren Bobby Kamberg (Elicia), Steven Kamberg (Samantha), Stephanie Kamberg, Jason Boone, Scott Boone (Andrea), PJ Vanderklis and Matt Vanderklis.

She was most proud of the great grandchildren Christina Boone, Hayden Kamberg, Hallie Jean Skillings, Killian Kamberg, Koah Kamberg, Anna Boone and is now in heaven with Jon Jon Vanderklis. She is missed so much already!

Love you always and forever… There will be a private service held August 4, 2023 for family and friends of our sweet angel.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Jean’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Marjorie Ellen Gaunt, 1921-2023

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Aug. 2, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Marjorie Ellen Gaunt was born on December 4, 1921, in Sacramento, CA. She passed away July 9th, 2023, at Fortuna Rehab and Wellness in Fortuna. She was 101 + 7 months loved.

Marjorie lived near Miranda for 63 years at her beloved home in the redwoods. She and her husband, Sid, were part of the charter members that founded the Miranda Seventh-day Adventist Church in 1953. She was an active member there until 2015.

Marjorie loved gardening; her flowers were her pride and joy. She provided flower arrangements for her church on a weekly basis. She also won numerous ribbons at the local flower shows. Her love of flowers began when she worked at the California Nursery in Niles, CA after her high school graduation.

She received her stenographer degree from Heald’s Business College after high school, which prepared her for future employment. Marjorie retired in 1983 from the Department of Parks and Recreation as an office manager and secretary for 21 years at Richardson Grove State Park, and at Humboldt Redwoods State Park

She was preceded in death by her husband and high school sweetheart, Nolan Sidney Gaunt, in 1999. She is survived by her sons: Alan (Nancy) Gaunt, Merle (Diane) Gaunt, and daughters: Jeanne Denenberg and Jan (Dale) Sifford, as well as eight grandchildren (one deceased), 11 great-grandchildren and numerous nieces and nephews.

A memorial service will be at a future date. Contributions in her memory can be made to 3 Angel’s Broadcasting Network, PO Box 220, West Frankfort, IL 62896, or to a charity of your choice.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Marjorie’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

(PHOTO) Here’s What the Government Says an Offshore Wind Project Would Look Like From Humboldt’s Shores

Andrew Goff / Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023 @ 2:22 p.m. / Infrastructure , Offshore Wind

Have you been wondering how the offshore wind development proposed for the Humboldt area might affect your peace and tranquility? The feds are here to attempt to address your concerns.

According to the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), the visual simulation below illustrates what the project’s visual impact would be should you find yourself looking out into the Pacific Ocean from Sue-meg State Park.

(Click to enlarge)

What are you looking at? A note about how to wrap your mind around this image from BOEM:

The simulations are intended to be viewed as large high-resolution printed panoramas with the printed image attached to curved stands and placed at a proper viewing distance based on the image width. The panoramas cover a field of view 124-degrees horizontally by 55-degrees vertically, which is consistent with the typical human field of view.

For example, a 36”-wide panorama image would be placed at a distance of approximately 16 inches from the viewer. The images viewed on this website are digital representations and the visibility of the turbines projected on a computer screen will depend on the scale at which the image is being viewed. Simply put, zooming in on the image will over-represent visibility and, conversely, zooming out will minimize visibility of the turbines.

That’s all well and good, you’re thinking. But what will these things look like at night? Hey, here’s another image to click.

PREVIOUSLY:

- Harbor District Announces Massive Offshore Wind Partnership; Project Would Lead to an 86-Acre Redevelopment of Old Pulp Mill Site

- Offshore Wind is Coming to the North Coast. What’s in it For Humboldt?

- ‘Together We Can Shape Offshore Wind for The West Coast’: Local Officials, Huffman and Others Join Harbor District Officials in Celebrating Partnership Agreement With Crowley Wind Services

- SOLD! BOEM Names California North Floating and RWE Offshore Wind Holdings as Provisional Winners of Two Offshore Wind Leases Off the Humboldt Coast

- California’s Aging Electrical Infrastructure Presents Hurdle for Offshore Wind Development on the North Coast

- Crowley — the Company That Wants to Build a Big Wind Energy Facility on the Peninsula — Will be Opening Offices in Eureka

- Harbor District to Host Public Meeting Kicking Off Environmental Review of Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal Project

Harbor District Officials Extend Comment Period for Environmental Review of Humboldt Bay Port Development Project

Isabella Vanderheiden / Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023 @ 1:54 p.m. / Energy , Infrastructure , Offshore Wind

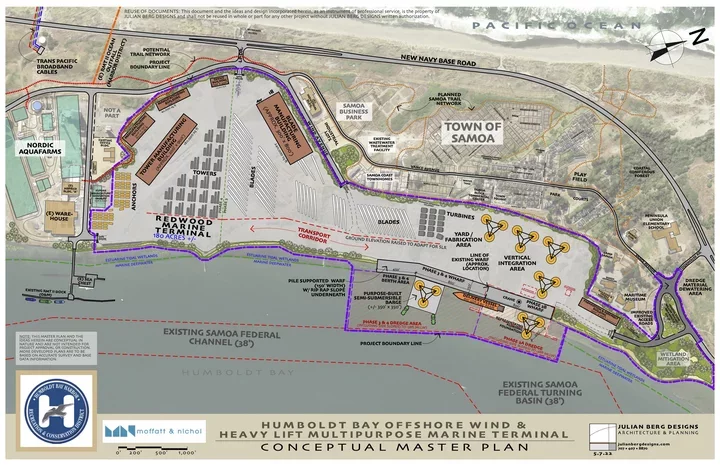

Conceptual rendering of the Humboldt Bay Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal | Photo: Harbor District

###

Folks interested in offering their two cents on the major renovations slated for the Port of Humboldt Bay have another month to submit their written comments.

The Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District has extended the scoping deadline for the Notice of Preparation of Draft Environmental Impact Report (DEIR) for the “Humboldt Bay Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Multipurpose Marine Terminal Project” on the Samoa Peninsula. The public review period will now end on Aug. 25.

Last year, the Harbor District entered into an agreement with Crowley Wind Services, a private marine solutions and logistics company, to build and operate a full-service facility to support offshore wind development along the West Coast. Once it’s fully built out, the state-of-the-art facility would be able to produce and ship the gigantic components needed for floating offshore wind turbines – everything from the blades and nacelles (the generator houses) to mooring lines, towers and transmission cables.

Harbor District officials held a scoping meeting last month to provide the public with an overview of the proposed project. During that meeting, several community members asked the Harbor District to extend the 30-day public comment period, the minimum required by state law, to give agencies, organizations and interested community members more time to submit their comments on the scope of the environmental analysis. The Harbor District obliged and agreed to extend the review period to 60 days.

Comments on the Notice of Preparation may be submitted via email to Rob Holmlund, director of development for the Harbor District, at districtplanner@humboldtbay.org. Those who prefer snail mail can send their comments in writing to: Rob Holmlund Humboldt Bay Harbor, Recreation and Conservation District P.O. Box 1030 Eureka, Calif. 95502-1030. All comments must be received or postmarked by Aug. 25.

More information on the project, including conceptual project descriptions, studies and public reports, can be found at this link.

###

PREVIOUSLY:

- Harbor District Announces Massive Offshore Wind Partnership; Project Would Lead to an 86-Acre Redevelopment of Old Pulp Mill Site

- Offshore Wind is Coming to the North Coast. What’s in it For Humboldt?

- ‘Together We Can Shape Offshore Wind for The West Coast’: Local Officials, Huffman and Others Join Harbor District Officials in Celebrating Partnership Agreement With Crowley Wind Services

- SOLD! BOEM Names California North Floating and RWE Offshore Wind Holdings as Provisional Winners of Two Offshore Wind Leases Off the Humboldt Coast

- California’s Aging Electrical Infrastructure Presents Hurdle for Offshore Wind Development on the North Coast

- Crowley — the Company That Wants to Build a Big Wind Energy Facility on the Peninsula — Will be Opening Offices in Eureka

- Harbor District to Host Public Meeting Kicking Off Environmental Review of Offshore Wind Heavy Lift Marine Terminal Project

- Humboldt Harbor District Officials Talk Port Development As Offshore Wind Efforts Ramp Up

Today is Your Last Chance to Apply for a Pass to Access Your Crops and/or Livestock During a Wildfire

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023 @ 1:37 p.m. / Emergencies

Photo via HCSO Facebook page.

###

The following information is from the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

Today is the LAST DAY to apply for your 2023 Restricted Area Access Pass.

Restricted Area Access Passes may permit qualifying agricultural producers/cultivators and/or commercial livestock operators to gain entrance to wildfire evacuation zones, or other restricted areas, to provide feed, water, medical treatment, and other care to large scale commercial livestock, and/or to tend to crops.

You must apply for this pass ahead of time, as we cannot process applications during an active wildfire.

Find out more about the program and apply at this link.

Two Young Children Removed From Fortuna Home During Meth Bust

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Aug. 1, 2023 @ 12:42 p.m. / Crime

Humboldt County Drug Task Force Agents press release:

On July 31st, 2023, Humboldt County Drug Task Force Agents served a search warrant at the residence of Jesse Rawlin Lussow (Age 47) located in the 2000 block of Hanna Court in Fortuna. After a multi-week investigation, the HCDTF believed Lussow was in possession of methamphetamine for the purpose of sales.

Upon arrival at the residence, Agents located Lussow inside and he was detained without incident. As Agents continued through the residence, they located two young children who were removed from the residence and placed in a safe area.

Once the scene was secure, Agents began searching the residence. In the garage area Agents located approximately 1.2 pounds of methamphetamine, 5 grams of cocaine, over $4,000 in US Currency, and digital scales.

Also located in the garage area, Agents observed a glass plate containing lose methamphetamine. The glass plate with the methamphetamine was being held on a shelf that was also storing what appeared to be snacks for children. Agents noted that the methamphetamine and cocaine located inside of Lussow’s garage, were in areas that were accessible to the children inside of the house.

HCDTF Agents contacted Humboldt County Child Welfare Services and advised them of the living situation for the two young children. After CWS was notified, the children were ultimately released to a family member.

Lussow was transported to the Humboldt County Jail where he was booked for the following charges:

- HS11378 Possession of a Controlled Substance for Sales

- HS11366.5 Operating/Maintaining a Drug House

- HS11350(A) Possession of Narcotics

- PC273A(a) Felony Child Endangerment

Anyone with information related to this investigation or other narcotics related crimes are encouraged to call the Humboldt County Drug Task Force at 707-267-9976.