Woman Dies After ‘Physical Altercation’ With Man Results in Apparent Stab Wounds to Both, EPD Says

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 5:08 p.m. / Crime

PREVIOUSLY: GOING DOWN: Eureka Stabbing

###

Press release from the Eureka Police Department:

On August 2, 2023, at about 6:37 p.m., Officers with the Eureka Police Department responded to the 100 block of W Sonoma Street in response to a 911 call of a physical altercation between an adult female and an adult male friend of her roommate.

Upon arrival, officers located the female and male and determined both had sustained wounds consistent with stab wounds.

Humboldt Bay Fire and City Ambulance arrived and transported both to a local hospital, where the female was ultimately pronounced deceased. The male was treated at the hospital for his injuries and released.

The exact details of the incident remain under investigation by the Eureka Police Department Criminal Investigation Unit. The female has been identified; however, her identity will not be released at this time, pending notification of next of kin.

This is a complex and active investigation and no arrests have been made. Anyone with information regarding this incident is asked to contact Detective Nunez at rnunez@eurekaca.gov or (707) 441-4109.

###

BOOKED

Yesterday: 4 felonies, 7 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Yesterday

CHP REPORTS

No current incidents

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: ‘We Will Not Accept the Response’: Students Remain Overnight in Cal Poly Humboldt’s Nelson Hall

RHBB: Humboldt County Road Construction Notice: Central Avenue

RHBB: Electrify Home Appliances and Improve Efficiency, Says Arcata

Governor’s Office: Governor Newsom releases 2025 judicial appointment data

(UPDATED With Photos) 41-Year-Old Fortuna Woman Arrested for Threatening to Kill Local Government Officials, Says Fortuna Police

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 4:31 p.m. / Crime

UPDATE, 5:15 p.m.:

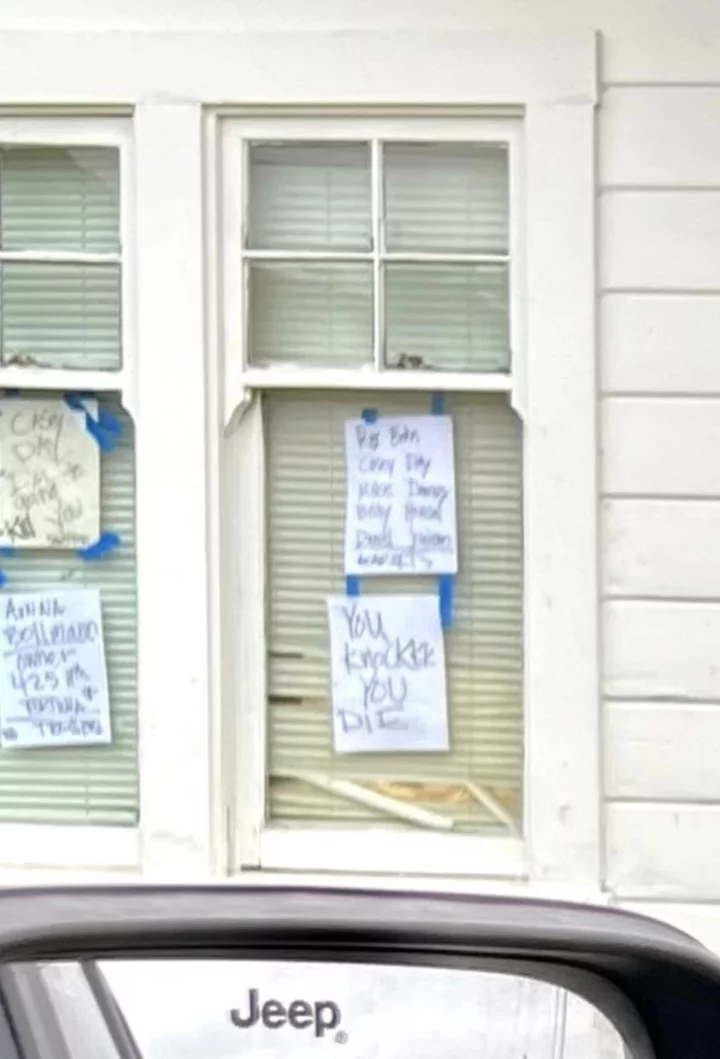

Folks on the Facebook page Fortuna Happenings have posted photos of the threatening messages allegedly posted to the windows of Aunna Bollmann’s home. Below are a couple of them, from Kristin Agajanian Ambrosini, republished with permission.

While the images are a bit blurry, some of the messages remain legible, including one addressed to the Fortuna police chief saying, “Casey Day I’m going to kill you.”

—Ryan Burns

###

Original post:

Press release from the Fortuna Police Department:

On Thursday, August 3rd 2023, at about 2:30 PM, Fortuna Police served a search warrant at the home of Aunna Sophia Bollmann in the 40 block of 11’ Street, Fortuna, California.

Aunna Bollmann, a 41-year old resident of Fortuna, had an active arrest warrant stemming from weeks of threatening and harassing phone calls to government officials. Aunna Bollmann had been threatening to kill elected County Officials, Elected City Officials, and City/County staff members via telephone, voicemail, and text message, and had posted similar threats on paper, which she posted in the windows of her home.

Over the past week, the threats became more direct and egregious prompting concern for the safety of community members and those she was threatening. The threats were not isolated to Fortuna Officials and were made to several officials in several jurisdictions throughout the Humboldt County region including Humboldt County and the City of Eureka. Section 422 of the California Penal Code makes it a felony for one to criminally threaten another. Additionally, section 76 of the California Penal Code also prohibits criminally threatening an elected official.

Bollmann wasbooked on her outstanding arrest warrant and additional charges will be submitted to the Humboldt County District Attorney for consideration and potential prosecution. As a result of the search warrant, documentation and digital evidence was recovered. The majority of written documents seized were specifically threatening to City and County Officials. As a result of this incident, Aunna Bollmann was transported and booked into the Humboldt County Jail.

(VIDEO) CITIZENS’ ARREST: Wabash Avenue Closed in Eureka After Reports of Gunfire; Motorist Flees and Crashes Into Parked Car

Ryan Burns / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 3:26 p.m. / Breaking News

Photos and video by Andrew Goff

###

The Eureka Police Department has been busy this Thursday attending to separate crime scenes a mere block from each other.

Wabash Avenue has been closed to through traffic between A and B streets after officers responded to reports of gunfire in the area.

Eureka Police officers responded to the scene and blocked the road with crime tape. A police services vehicle is also blocking the intersection of Wabash and B in front of the Stop and Shop convenience store.

“Officers located shell casings but have not identified a suspect or [determined] if there are any victims,” EPD Public Information Officer Brittany Powell said. “The area is being searched for evidence and surveillance.”

Officers initially appeared to be focusing their attention on a two-story, seafoam green building at the southeast corner of Wabash and A streets, according to the Outpost’s Andrew Goff, who is on the scene. The officers are telling pedestrians that this is an active crime scene.

As if that weren’t enough, around 3:40 p.m., a white Mercedes sedan sped past the crime scene and turned east onto Del Norte Street, where it promptly ran into a parked vehicle, Goff reports.

“Lots of neighbors came out of their homes and confronted the man, who used a racial epithet towards one of the bystanders,” he tells us. Residents surrounded the man, pulling him to the ground. One woman informed him that this was a citizen’s arrest.

It’s unclear, at this point, if the crash-and-flee incident is related in any way to the police response on Wabash. (UPDATE: EPD tells us the individual involved in the collision is 21-year-old Miles Armstrong.)

Warning: The video below contains racial epithets and partial nudity.

‘30,000 Salmon’ Art Installation Inspired by Klamath River Fish Kill of 2002 Reemerges at Morris Graves to Celebrate the Klamath Dam Removals

Stephanie McGeary / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 2:26 p.m. / Art , Fish , Klamath

The “30,000 Salmon” Art Installation at the Morris Graves Museum of Art in Eureka | Photos: Stephanie McGeary

###

After nearly two decades sitting in boxes in an attic, “30,000 Salmon” — a huge, collaborative art installation — is again seeing the light of day and has been reinstalled at Morris Graves Museum in celebration of the removal of the dams on the Klamath River.

Congressman Jared Huffman, who has helped support the dam removal efforts, came to an advanced look at the installation on Thursday morning, joined by artists, teachers and community members who contributed to the project.

Huffman has been working to support Klamath River restoration efforts since he was elected to Congress 11 years ago, he said. Though there is still a lot of work to be done and the reemergence of this installation comes at a time when the Klamath’s salmon population is among the lowest on record and salmon fishing season has been officially canceled, he is happy to see the dam removal process finally moving forward after decades of the process struggling through political red tape.

“I think there’s a powerful message here,” Huffman told the Outpost while gazing at the piece, which hangs from the ceiling in the middle of the museum. “We’ve kind of come full circle, but in a better way because this year we’re celebrating the removal of the Klamath dams. And we still haven’t fixed all the problems on the Klamath River, but getting these dams out is the biggest piece of bringing these rivers back to life.”

Rep. Jared Huffman and artist Becky Evans

The installation was first put together in 2002 by local artist Becky Evans as a response to the devastating Klamath River fish kill that left more than 30,000 salmon dead (around 30,000 was the initial number reported, but later counts estimated that upward of 70,000 salmon died) as a result of water diversion to the Klamath Basin during a drought year.

To bring attention to the ecological disaster, Evans reached out to artists, teachers and students around Humboldt to help contribute to the art project. The result was 30,000 individual pieces, including drawings, cutouts, papier-mâché and ceramics suspended in the shape of a fish, with objects below. Originally, the art exhibit was installed at the now-closed First Street Gallery in Old Town Eureka

At the time of the original installation, Evans told the Outpost, former North Coast Rep. Mike Thompson extended an invitation to take the installation to be displayed in D.C. But after Evans and her assistants boxed up the entire piece, it turned out that there was not enough space or money to transport the piece to the capitol. So, Evans put the deconstructed sculpture pieces in her attic, where they sat for 19 years.

“My idea was to save it all until the dams come down, if I live that long,” Evans told the Outpost at the Morris Graves on Thursday. “And I’m happy to have lived that long.”

Several of the teachers whose students had contributed to the original project were present to view the sculpture, including Moureen McGarry, who taught art at Sunset Elementary at the time of the original installation. McGarry’s kindergarten, first grade and second grade classes created ceramic pieces, which are scattered in a fish shape on the gallery floor. Students in her after-school art program also painted salmon designs on swaths of silk that are hanging among the thousands pieces of fish art.

“It was a really important educational moment for [the students] to recognize that there is an impact in what we do as humans to this planet and that it affects all of us,” McGarry told the Outpost, recalling what the process was like for her students so many years ago.

Lee Roscoe-Bragg, who taught at Zane Middle School, had her seventh-graders create a series of fish kites for the project back in 2002 and said that she is thrilled to see the pieces displayed again, adding that she remembers how much the students enjoyed viewing the installation the first time it went up. She hopes that some of those students, who are now full-grown adults, will be able to come see the piece again at the Morris Graves.

“The students were very enthusiastic,” Roscoe-Bragg said. “While they didn’t understand exactly how it was all going to come together, they were really excited to be part of such a huge contribution.”

The installation is also accompanied by a short documentary film created by married couple Ken Magnuson and Barbara Morrison that highlights the original project and the catastrophic event that inspired it. Magnuson and Morrison edited the full 25-minute film down to a 10-minute feature that plays on a loop next to the exhibit.

If you would like to view “30,000 Salmon,” the exhibit officially opens to the public this Saturday, Aug. 5 and will be on display at the Morris Graves Museum of Art — 636 F Street, Eureka — through Sep. 19. Evans hopes that those who help contribute to the piece and other members of the community will come to experience this impressive work that both illustrates the devastation that occurred on the Klamath River and celebrates the progress that has been made since.

“It’s about all the people who contributed and all the people in the tribes, in the agencies – the individuals who have not given it up and worked so hard for so many years,” Evans said. “It just brings tears to my eyes that this has happened and I’m considering this a celebration.”

###

NOTE: This article has been changed to reflect that 30,000 was the initial number of salmon reported dead on the Klamath in 2002, and this is why Evans’ project focused on that number. Other counts estimated that upwards of 70,000 salmon died.

California Could Borrow a Record-Breaking $35 Billion to Tackle the Housing Crisis. Will Voters Go Along?

Ben Christopher / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 8:56 a.m. / Sacramento

Illustration by Adriana Heldiz, CalMatters

California voters regularly name out-of-reach housing costs and homelessness as among the most important issues facing the state.

Now lawmakers are calling their bluff. Next year the electorate will likely get the chance to put unprecedented gobs of money where its mouth is.

There’s the $10 billion bond proposal, spearheaded by Oakland Democratic Assemblymember Buffy Wicks and currently slated for the March ballot, that would replenish the coffers of some of the state’s premier affordable housing programs. If a majority of voters approve, it would be the largest housing-related IOU that California has issued since at least 1980.

Next, there’s the $4.68 billion measure, backed by Gov. Gavin Newsom and also scheduled for March, to build housing and expand psychiatric and substance abuse treatment for homeless Californians. That would be the largest-ever expansion of behavioral health funding in California, according to the governor’s office. As a housing-related bond, it would also be the third largest such measure in recent memory.

But both of those state measures could be dwarfed by a third proposed at the regional level. The recently created Bay Area Housing Finance Authority, tasked with funding affordable housing projects across the nine counties that surround the San Francisco Bay, is still figuring out exactly how much it wants to ask voters to sign off on in November 2024. But it could be as much as $20 billion.

Three of the largest housing bonds in California history would seem to be great news for housing advocates.

So why are some so worried?

“I’m a runner. I’ve never run my three best races in a row,” said Louis Mirante, a lobbyist with the Bay Area Council, where he focuses on housing legislation.

With lawmakers considering a bevy of other bond measures in 2024 that could total as much as $80 billion — more potential debt than the state has put on the ballot since at least 1980, even adjusting for inflation — the sheer scale of the state’s potential borrowing plans could test the upper limit of what voters are willing to stomach.

“It’s conventional wisdom that if you put a bunch of bond proposals in front of voters, they get overwhelmed and are like ‘I don’t want to pay all of this money, so I don’t want to pay any of this money,’” said Mirante.

And even before the question is put to voters, lawmakers will have to negotiate what goes on which ballot in the first place. Unlike the other initiatives, constitutional amendments and referenda that will already crowd the 2024 ballot, bond measures can only be put before voters with a vote by the Legislature and approval of the governor.

“There is only so much capacity that the state has for debt,” said Ray Pearl, executive director of the California Housing Consortium, which lobbies for more affordable housing construction in the Legislature. “And politically, for the governor and the Legislature, there’s only so much they are willing to take on.”

Lawmakers may not have long to hammer out those negotiations. Any bonds bound for the March ballot need to clear the Legislature by the end of the session on Sept. 14. Branch-on-branch negotiations have been slow to get going so far, but may ramp up once the lawmakers return from recess on Aug. 14.

“We want to make sure that we’re presenting a ballot to the electorate, in as much as we have the ability to, that is thoughtful and aims to tackle some of our tougher challenges, but in a way that doesn’t confuse voters with, like, ‘Here are your ten opportunities to vote for housing,’” said Wicks. “I anticipate over the next probably two or three months that we’ll start landing some of these planes.”

Not everyone in housing world is so concerned. The mere fact that so many housing-related bond measures are vying for space on next year’s primary and general election ballots is a sign that the state’s affordability crisis is finally getting the political and fiscal attention it deserves, said Kate Hartley, who directs the Bay Area Housing Finance Authority.

“I don’t know what voters will think about” a glut of bond measures next year, she said. “But I do know that voters really care about this and they want solutions.”

‘You name it, there’s a bond’

Some of the most competitive real estate in California these days is a spot on either of the two 2024 ballots.

The Legislature is considering as many as ten borrowing measures for either the March primary or November general election next year. Among them are competing school bonds, climate and flood protection proposals and a bond aimed at fighting the fentanyl crisis. Though it isn’t likely that all will make the cut, taken together, they come with a collective debt of at least $80 billion, with the price tag on one proposal still undetermined.

“We have so many crises for people facing so many different challenges,” said Chris Martin, policy director with Housing California, an affordable housing advocacy group. “You name it, there’s a bond for it being considered in the Legislature and there’s only so much bonding authority.”

The Newsom administration has reportedly set the borrowing limit for both of next year’s ballots at $26 billion, but the final number is likely to be ironed out in negotiations with legislative leaders.

Whatever the borrowing cap, it’s as much a question of political arithmetic as it is budget math. There is no legal limit on how much debt voters can approve in a given election. Budget analysts keep their eye on different metrics comparing the state’s debt payments to its discretionary cash cushion, its overall budget or the total size of the California economy. Projections of future interest rates and future budget surpluses and deficits also get considered.

One measure — the ratio of the state’s annual debt payments to the budget’s discretionary “general” fund — currently sits at roughly 3.5%, depending on how you measure it. That’s a tad high compared to other large states, but it’s far lower than it has been in the past. Keeping that figure below 6% is “generally considered prudent,” said H.D. Palmer, a spokesperson for the California Department of Finance.

There’s no evidence that voters have any of that in mind when they vote “yes” or “no.”

Californians have generally been perfectly happy to put big projects on the state’s credit card. That may be because bond proceeds are typically directed at politically sympathetic causes and the downsides of borrowing — higher debt payments in future years — are more abstract for the average voter.

Since 1980, the electorate has signed off on more than 75% of all state bonds put before them, approving $182 billion in new debt and rejecting only $42 billion. In contrast, voters have approved only about 40% of all non-fiscal propositions.

The prospect of ‘bond fatigue’

There are clear exceptions. Sometimes the voting public, presented with particularly eye-popping sums, gets into a tight-fisted mood.

The November 1990 election was the most bond-happy in recent history, with 14 borrowing proposals in total. Voters batted down 12 of them.

A more recent example of bond failure: The March primary election in 2020, when voters rejected what would have been the largest school bond in California history, a $15 billion IOU. One of the possible post-election explanations offered at the time: Voters, saddled with a bumper crop of borrowing measures at the local level, succumbed to “bond fatigue.”

Now, with 2024 approaching, some housing advocates worry the electorate is susceptible to the same condition.

As a matter of fiscal reality, the two major housing proposals — the affordable housing measure and the Newsom-backed mental health bond — are dipping from the same pool of fiscal overhead and electorate will.

But as policies — one that supports the construction of more housing and the other that boosts behavioral health treatment capacity for people living on the street — they could very well complement one another. According to the governor’s office, his mental health bond would allow for the shelter and treatment of 10,000 more unhoused Californians. As negotiations kick into gear, some proponents of both measures are hoping the governor and legislative leaders will see things that way.

“If you have temporary shelter beds and services for an individual suffering from mental health or substance abuse disorder but no affordable housing, that person is likely going to return to homelessness,” said Alex Visotzky, senior California policy fellow at the National Alliance to End Homelessness, which supports the affordable housing bond and is still reviewing the mental health-related proposal. “Conversely if you have affordable housing, but no services available, then that individual is going to struggle to maintain their housing.”

“We feel the Legislature has a real opportunity to connect the two,” he said.

A race against the clock

Politically, California voter frustration with unaffordable housing and homelessness could cut one of two ways.

Voters who believe public dollars are poorly spent may not welcome proposals to throw more money at the problem.

Earlier this year, lawmakers directed the state auditor’s office to dig into how the state’s homelessness funds are actually being spent. A 2020 audit from the same office called for an “overhaul” of California’s “cumbersome” affordable housing funding process, after the state allowed $2.7 billion in bonds to expire untapped. (The state application process has since been streamlined.)

But many housing developers hope it will translate into the popular political will to ratchet up the spending. In fact, they’re counting on it.

Of the roughly 2.5 million units the state Housing and Community Development department says California communities need to build over the next eight years to make up for years of under-building, roughly 1 million must be set aside for people earning less than 80% of the median income in their region.

But that planned-for boom in affordable housing won’t materialize without some extra help, said Heather Hood, who manages the northern California market for Enterprise Community Partners, an affordable housing developer.

“The state’s been, on one hand, very clear about what the ambitions and goals are,” she said. “And yet (it) hasn’t supplied the resources to enable that to happen.”

It’s unclear how many additional units $10 billion in extra state funding could bring online. The cost per-unit of affordable housing climbs year after year, occasionally exceeding $1 million. By that math, the eye-popping face value on the bond would only be enough to fund 10,000 new units. But state funding is almost always used to supplement private, federal and local sources of cash.

“Housing isn’t completely paid for by public dollars,” said Hood. “Having this kind of security in the public realm means that there’s more security in the private realm and so it smooths the pipeline.”

The last time the state turned to the voters to fund affordable housing construction was in November 2018. Voters overwhelmingly approved Proposition 1, giving the state the go-ahead to borrow $4 billion. Of that, about half went toward the construction, rehabilitation and preservation of income-restricted rental housing. The remainder was meant to be split between programs that promote homeownership, the construction of farmworker housing and other housing-related infrastructure projects.

The timing of Wicks affordable housing bond next year is also no coincidence. With a little over $656 million remaining, that Prop. 1 funding is expected to run dry by next year

But even if voters are feeling generous next year and sign off on each of the housing bonds on the ballot, Wicks said she is only just getting started.

“We have to have significant ongoing investments for a serious amount of time in order to crawl out of where we are right now,” she said. That could mean putting yet more bond measures on the ballot or dedicating more money from the state budget on an ongoing basis. “That’s something that I want to work on next year. And probably the year after that.”

###

CalMatters.org is a nonprofit, nonpartisan media venture explaining California policies and politics.

OBITUARY: Bernice Francis Capeder, 1930-2023

LoCO Staff / Thursday, Aug. 3, 2023 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Bernice Francis Capeder (née Turner) of Santa Clara, CA entered into eternal rest on December 24th,

2022 in Santa Clara, CA at the age of 92 of natural causes.

One of three children, she was born in Ferndale on December 10, 1930 to Henry Sanford Turner and Helen Bernice Hansen. She had two brothers, Ron and Wayne Turner, who preceded her in death.

Growing up in Port Kenyon, her beloved grandparents, Hans and Esther Hansen, stepped in to help raise her. She was close to her stepfather Luther Jensen who was a father figure in her life. She attended Fortuna High and was crowned the 1951 Fortuna Rodeo Queen. A natural beauty, she caught the eye of Pierre (Ben) Benito Capeder in high school while roller skating.At the age of 22, she married Ben on June 22, 1952 at the Church of the Assumption in Ferndale and together they raised a family of six children.

Ben was in the Air Force early on and the young family moved from place to place as their family grew. She would recall, years later, how hot it was in Mississippi while stationed there and welcomed the chance to return to our cooling coastal fog. The seaside was always her favorite place and she would tell tales of the abundance of the Salt River and digging for giant clams in her youth.

Born a farmer girl in rural Humboldt County, she developed her trademark toughness and positivity. Stubbornly optimistic, “Just be positive” was her tagline, a message that we all could benefit from. She loved her gardening, flowers (especially roses), and her many canine companions. Her whimsical garden, filled with gnomes, lights and fairies, is legendary and those who have seen it know it as almost magical at night.

Most of all, she loved her family. Ben’s parents and siblings were always dear to her heart and she considered them her own. As a mother of six, it could be difficult to provide all the love and attention they needed in their head-strong years, but she endured and loved her family deeply, along with her adored eleven grandchildren and nine great grandchildren. Talking about their adventures or seeing them always made her eyes light up. Her happiest times were whenever her house was filled with family laughter and sharing a good meal while telling the tales of life.

Bernice’s remains will be interred with Ben on August 4th, 2023 at Ocean View Cemetery in Eureka at 10 a.m. She will be missed by the many who loved her. May her memory be eternal.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Bernice’s loved ones. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

Eureka City Council Reviews ‘Big Picture’ Plans for the City’s Waterfront, Approves New Downtown Parking Fees and More!

Isabella Vanderheiden / Wednesday, Aug. 2, 2023 @ 5:04 p.m. / Local Government

Screenshot of Tuesday’s Eureka Council meeting.

###

The Eureka City Council took its second look at the draft Waterfront Eureka Plan during Tuesday’s regular meeting, a plan that would revamp the heart of the city.

The project area covers all three “districts” that have been defined by the city — the “Old Town District,” the “Library District” and the “Commercial Bayfront District.” Similar to Arcata’s Gateway Area Plan, the Waterfront Eureka Plan aims to streamline housing approvals and accelerate mixed-use development in the northern portion of Eureka, between Humboldt Bay and downtown.

Image: City of Eureka

“The purpose of the plan … is to provide a roadmap for the development and redevelopment of vacant and underutilized sites and buildings along and near Eureka’s central waterfront,” Caitlin Castellano, a senior planner for the City of Eureka, explained during Tuesday’s meeting. “[It also] plans for at least 115 housing units to be built, which the plan contemplates happening by 2027.”

Unlike the city’s General Plan, the Waterfront Eureka Plan is a “specific plan” which combines a policy document with zoning regulations to “set realistic development expectations while also signaling the big picture of the plan and vision for a particular area,” according to the staff report.

The plan must adhere to the goals of Eureka’s 2040 General Plan and the Land Use Plan portion of the city’s Local Coastal Program (LCP). Castellano noted that the LCP update is still in progress but said the city will use the environmental analysis collected through the Waterfront Eureka Plan process to better inform the LCP update.

The city has hosted several public forums on the planning process and received hundreds of comments from community members on the subject. Something that has come up time and time again, Castellano said, is the importance of balanced development.

“People wanted to make sure that there was a balance between the new residences and the visitors to the area while maintaining existing resources for Eureka residents who live and visit the waterfront,” she said. The community’s feedback helped staff develop the guiding principles of the document, which can be found on page 54 of the draft document.

Turning to questions from the council, Councilmember Leslie Castellano asked if staff has worked with the private parking lot owners to better accommodate parking needs for both the private and public sectors. “I just, I look at all of that parking and I just think there could be potentially better ways of collaborating around how parking is used on private areas as well as public,” she said.

Senior Planner Castellano said she had not spoken directly to individual property owners but said staff has reached out to the Eureka Chamber of Commerce and Eureka Main Street on the subject. “They sent emails to all of their constituents to attend stakeholder conversations, which didn’t have a very good turnout.”

City Manager Miles Slattery said he has “definitely been contacted by private property owners about different parking lots,” some of whom wanted to sell the lots to the city while others wanted to offer them up for parking structures.

Councilmember G Mario Fernandez thanked staff for being aware of the potential displacement of existing residents as a result of gentrification. “I really do commend you for thinking that far forward and trying to mitigate the impact on the residents along those tracks,” he said. “What – if anything – has staff considered moving forward with that? What are the plans that are being considered, if any?”

Senior Planner Castellano said staff didn’t have any plans just yet.

Councilmember Scott Bauer said he really appreciated the document’s focus on walkability throughout the project area, adding that he “love[s] the idea of being able to stroll in on the street and not to worry about cars.”

“The thought of, you know, building housing and then having to travel to get groceries … it used to be that there were grocery stores close to your home,” he said. “The idea of trying to incorporate as much of that kind of living style is exciting.”

After a bit of additional discussion on the matter, the council agreed to accept the report but did not take any action on the item.

Staff will present the final Waterfront Eureka Plan and the associated environmental documents to the Eureka Planning Commission during a public hearing in September. If everything goes according to plan, the final document will be presented to the city council at a public hearing in October.

Those interested in commenting on the draft plan have about a week to do so. The public review period will close on Friday, Aug. 11. Click here to access the comment form.

Parking Fees = Parking Improvements

The council also approved a proposal to change city code to allow for the implementation of pay-to-park parking in four city-owned lots to “better manage the city’s existing parking resources” and “improve utilization and access to parking” throughout Eureka’s Old Town and Downtown districts.

The new pay-to-park lots are located at:

- the southwest side of 3rd and E streets (by the Sea Grill)

- the northeast side of 3rd and E streets (by The Madrone Brick Fire Pizza and Taphouse)

- the southeast side of 1st and E streets (behind Los Bagels) and

- the southeast side of 2nd and H streets (sorta near Smug’s Pizza).

The parking fees – $0.50 per hour – will fund several improvements throughout Old Town and Downtown Eureka, including parking lot wayfinding signage, website updates and outreach of existing parking resources and long-term upgrades to the parking lots, such as striping/resurfacing/lighting improvements and the creation of a parking lot shuttle program, according to the staff report.

A silver lining: The city will increase the existing parking time limit zones from two hours to four hours — a small but valuable consolation, especially for folks working in Old Town and Downtown.

Councilmember Fernandez asked if staff would be willing to allow for free parking on Saturdays, as it does currently. Public Works Director Brian Gerving stood by staff’s recommendation to only allow for free parking on Sundays and certain holidays.

Councilmember Castellano asked if staff had any plans for additional funds collected from the lots after the aforementioned improvements are taken care of.

“There definitely will be projects that can take up any of the revenue that the parking program can generate for the foreseeable future,” Gerving said. “In the event that we run out of projects – which I can’t forecast at this point – then, you know, we could consider doing something different with those funds.”

Gerving added that, if approved, the parking fees would go into effect on Sept. 1. “That’s if we can get the infrastructure installed by then,” he added.

Councilmember Bauer made a motion to adopt staff’s recommendation. Castellano offered a second.

Fernandez returned to the issue of free parking on Saturdays and asked if his fellow council members would be willing to amend the motion. “Is there anybody else amenable to leaving Saturdays as they are?” he asked. “Because I find it difficult to vote for that without Saturday’s remaining free parking.”

Gerving noted that Saturdays are currently enforced because that’s what the signage has reflected in most cases. “It’s just the municipal code language that was incorrect and inconsistent with what that signage said,” he added.

Fernandez opted to “leave it at that” and the motion passed in a 3-1 vote with Fernandez dissenting and Councilmember Kati Moulton absent.

###

Other notable bits from Tuesday’s meeting:

- The council also approved a request to declare a little slice of city-owned land at Fifth Street and Myrtle Avenue as surplus.

- The council also received a report regarding privacy concerns surroundings accessory dwelling units (ADUs) in neighborhoods. However, Cristin Kenyon, the city planner presenting the report, was feeling under the weather and the council opted to revisit the subject at a future date.

- The council also received a presentation from Fogbreak Justice LLC, regarding the city’s workplace diversity, equity and inclusion efforts. The council accepted the report but did not take any action on the matter.