Sheriff’s Office Investigating Apparent Murder-Suicide in Weitchpec

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 4 @ 9:12 a.m. / Crime

From the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office:

On Feb. 3, 2026, at 8:47 p.m., Humboldt County Sheriff deputies responded to a residence located in the 900 block of Lewis Rd., in Weitchpec to a reported possible murder- suicide.

Upon arrival, deputies located two individuals deceased inside the residence. Based on the preliminary investigation, the incident appears to be consistent with a murder-suicide. The identities of the deceased are being withheld pending notification of next of kin.

The Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office Major Crimes Division is actively investigating the incident and is working closely with the Yurok Tribal Police.

No additional information will be released at this time. Updates will be released as the investigation continues and as appropriate.

Anyone with information about this case is encouraged to call the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office at (707) 445-7251 or the Sheriff’s Office Crime Tip line at (707) 268-2539.

BOOKED

Today: 6 felonies, 9 misdemeanors, 0 infractions

JUDGED

Humboldt County Superior Court Calendar: Friday, Feb. 13

CHP REPORTS

0 SR36 (RD office): Chain Control

250 Mm271 S Men 2.50 (HM office): Closure of a Road

ELSEWHERE

RHBB: RV Fire Near Founders Grove

Politico Magazine: The Friday Read ‘The Industry Comes In and Kills the Work of Local Citizens’

The Guardian: Anatomy of an upset: how Ilia Malinin lost Olympic figure skating gold

The Hill: Democrats say Trump’s climate rollbacks ‘corruption in action’

A Quest for Historical Accuracy Delayed Renovations of U.S. Coast Guard Station Humboldt Bay, But the Project is Finally Complete

Ryan Burns / Wednesday, Feb. 4 @ 7:54 a.m. / Government

The U.S. Coast Guard Station Humboldt Bay — a.k.a. the Humboldt Bay Life-Saving Station — in all its renovated glory. | Photo by Ryan Burns.

###

PREVIOUSLY

###

Well, lookie there! The historic U.S. Coast Guard Station Humboldt Bay has emerged from its chrysalis with a brand-new set of historically accurate windows and doors.

Just over a year ago, the exterior of the building, which is also called the Humboldt Bay Life-Saving Station, was almost entirely wrapped in white plastic, giving the structure a circus tent vibe while sparking curiosity among passersby.

The reason for the wrap, it turned out, was lead paint remediation. The handsome edifice, located on the North Spit near the entrance to Humboldt Bay, was built way back in 1936 (replacing the original 1878 structure), and the old paint still adhered to the siding.

As we reported back in December 2024, the Coast Guard hired local contractors to complete an extensive renovation project, which involved remodeling the bathrooms and replacing all the siding, windows and doors.

The work was supposed to be completed by last summer, but Lieutenant Junior Grade Nathan O’Brien, public affairs officer with USCG Sector Humboldt Bay, tells the Outpost that the project wasn’t completed until late last week.

“The primary cause for the delay was an unforeseen challenge in procuring windows and doors that met the stringent historical requirements of the building,” O’Brien explained in an email.

Why such stringent requirements? Well, the three-story structure has been recognized as the best example of a New Deal-era “Roosevelt Style” Coast Guard station in the western U.S., and in 1979 (or perhaps 1977) it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

As such, history buffs care very much about this building. In 2020, in a story about the planned removal of the station’s defunct marine railway, the Outpost cited historian Ralph Shanks’ description of the building as “the apex of Coast Guard architecture.” The Coast Guard itself swooned in an official report that the detailing, “such as the period exterior door and window moldings, classical columns, balustrades, gable brackets and ironwork, is especially fine.”

(There are some nice photos of the building at this website. The shots were taken after completion of a roof-replacement project that also required strict historical accuracy.)

O’Brien explained that the California State Historic Preservation Office demanded historical accuracy with the renovation project.

“The station, a landmark in the region, required specialized materials to maintain its unique architectural profile,” he explained in an email. “The prime contractor faced difficulties in sourcing a supplier capable of meeting these exacting standards.”

Custom-built windows and doors were expected to arrive in March but not delivered to the site until October.

“Despite this setback, the contractor has done excellent work on the project,” O’Brien said. “The renovation has been comprehensive, ensuring the building is fully restored to serve the needs of the Coast Guard while honoring its storied past.”

The Coast Guard Air Station located at the Humboldt County Airport in McKinleyville was commissioned in 1977. However, the Life-Saving Station on the peninsula remains an active part of the agency’s search-and-rescue infrastructure, housing a 47-foot lifeboat, among other resources.

New Transit Housing Bill Revives California’s Democratic Divisions Over Local Control

Nadia Lathan / Wednesday, Feb. 4 @ 7:52 a.m. / Sacramento

This story was originally published by CalMatters. Sign up for their newsletters.

###

Just months after lawmakers enacted major reforms to speed up home and apartment building, a new proposal seeks to force even more cities to allow housing near major transit hubs. It has reignited divisions among Democratic lawmakers who are wary of the state telling cities how and where to build.

San Francisco Democratic Sen. Scott Wiener’s Senate Bill 677 seeks to close a loophole that backers of the bill say some cities are using to get out of last year’s reforms intended to allow more apartments to be built near major bus and train stations.

A small group of Democrats who opposed last year’s law refused to support Wiener’s new bill seeking to force cities to comply with the new transit-related building requirements. The bill widens the definition of what a passenger rail is. It passed and advanced to the Assembly despite their objections.

The pocket of Democratic resistance contrasts with the Democratic-controlled Legislature’s appetite for sweeping housing reform it embraced last year. Last summer, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed legislation that repealed longstanding environmental protections allowing many developments to bypass environmental reviews, which can result in long delays and costly litigation.

Legislators last year also enacted the transit-oriented housing reforms, but some cities such as Solano Beach have been trying to find a way out of the new requirements by claiming they don’t have a major transit station, even though critics maintain they do. Wiener’s bill seeks to expand the definition of what counts as a transit station and close the loophole.

That didn’t sit well with some Senate Democrats.

Last week, seven of them joined Republicans to oppose Weiner’s proposal, including Catherine Blakespear and Lola Smallwood-Cuevas, of Los Angeles. The pair voted ‘no’ in a rare and forceful show of public opposition toward a fellow Democrat’s bill.

“I come from local government, and it’s hard for me to support that,” Blakespear said in an interview. She represents the San Diego County beach town of Encinitas, where she used to be mayor.

Local officials worry that building more apartments around transit centers could change the character of their communities with the potential for more traffic and less parking, she said.

“A community like Solano Beach is a low-density community with residents who have chosen it for that reason,” Blakespear said, referring to a city in her district that opposes the legislation.

Los Angeles and suburban cities in San Diego County have said the new transit-focused building requirements are vague and confusing, and they need clarity about which cities it applies to.

“We just worry that the definition change could be an expansion of where SB 79 applies,” League of California Cities lobbyist Brady Guertin said at a January committee hearing, referring to the bill Newsom signed into law last year.

Wiener, who also authored last year’s bill, said he plans to introduce more follow-up legislation to address how cities should implement the far-reaching statute, which will affect parts of Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco counties.

Wiener’s office did not return CalMatters’ interview requests.

A reversal of typical voting patterns

Blakespear’s decision to vote ‘no’ goes against her normal voting behavior.

Her votes have historically aligned with pro-housing group California YIMBY on bills 96% of the time from 2023 to 2025, according to the CalMatters Digital Democracy database.

California YIMBY is one of the bill’s sponsors, and the city of Encinitas, which has previously been sued by the state for ignoring state housing laws, opposes it. Many residents also still attribute the city’s biggest issues such as homelessness to Blakespear’s tenure as mayor more than four years ago.

And, similar to most Democrats, Blakespear also almost never vote

A reversal of typical voting patterns

s against the bills pushed by the Legislature’s supermajority.

Out of 2,161 opportunities last year, Blakespear voted “no” just 14 times — less than 1% of the time.

Smallwood-Cuevas also did not support last year’s transit-focused housing bill. Smallwood-Cuevas also did not support last year’s transit-focused housing bill. She represents Los Angeles, where Mayor Karen Bass has expressed concerns about the state dictating housing policy.

“We must streamline the production of housing for all Angelenos. However, we must do so in a way that does not erode local control,” Bass said in a letter urging Newsom to veto last year’s measure.

A spokesperson for Smallwood-Cuevas said she was not available for an interview.

Five Democratic senators also declined to vote on Weiner’s latest housing measure last week. Not voting counts the same as voting “no,” and is a tactic lawmakers regularly use to avoid angering colleagues or influential lobbying groups.

The tensions over this latest proposal come as lawmakers continue to debate measures this year to tackle the state’s housing crisis.

Democrats have already advanced a bill for a $10 billion affordable housing bond measure they want placed on the November ballot.

Meanwhile, one other housing-related bill faced even stronger resistance from Democrats. Democrats on the Assembly Judiciary Committee spiked a proposal to cap rent increases last month amid opposition from landlord groups and lawmakers who were leery of interfering with the rental-housing market.

###

Digital Democracy’s Foaad Khosmood, Forbes professor of computer engineering at Cal Poly San Luis Obispo, contributed to this story.

OBITUARY: John Lennord McGee III, 1953-2026

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 4 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

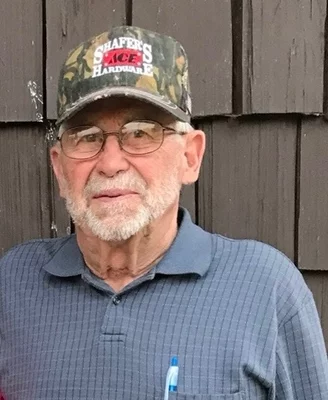

John Lennord McGee III

September 15, 1953 -

February 2, 2026

It is with great sadness that I announce the passing of my dad, John Lennord McGee III, age 72. Dad passed away peacefully on February 2, 2026, at Fortuna Rehabilitation and Wellness Center. Born in Littleton, New Hampshire, to John McGee II and Jessica McKinney, Dad lived a life of strong will and encouraging love.

Dad spent his childhood in New Hampshire until age 10. Facing neglect and feeling unaccepted, he left home to find his way in life alone. Not even a teenager, he began hitchhiking across the USA. On his journey, he stopped in Idaho and Oregon and eventually settled in California.

When finally settled in California, Dad found his happy place and felt a connection to Humboldt County, calling it his home for the rest of his life. Dad made friends everywhere he went. He was a talker, a storyteller, a jokester. Sometimes, his stories were so absurd we wondered if they were really true. Deep down, though, Dad was a lover, and he loved with all his heart because he knew what it felt like to not be wanted or loved.

Dad worked for Louisiana Pacific for 25 years as a resaw and lumber millwright in Samoa. He was well respected at his job and was very proud of his work. I will say he was one of the hardest workers. In fact, anyone you would talk to would say the same thing. Dad met two of his lifelong friends at Louisiana Pacific: Chuck Lewis and Lee Coffman. Both men provided Dad with joy to his heart and, for once, made him feel like he belonged.

Living out in Fairhaven, my dad met my mom, Sandra Nelson. After dating for some time, they married, and soon, a family of their own was started. Dad had three children with my mom and two other children from previous relationships. My dad had a total of five kids, each one providing love and support he cherished up until the end.

Dad is survived by his children and their spouses, Anthony McGee, Timothy McGee, April Luke, Lisa Diaz, and Paul Diaz, and after 40 years of missed time, Cassie Lilyblad Bumgardner.

Dad is also survived by his grandchildren, Brianna McGee, Brian Luke Jr., Ophelia Warren, Sawyer Warren, and Caspian Diaz.

I want to thank the following friends for being with Dad after his fall and cancer diagnosis: Johnathan Newell and Aleia Torres. You two meant the world to Dad and I can’t thank you enough for always lending a hand at a moment’s notice.

To Pastor Chuck Clark: Thank you a million times over for your prayers and sitting with Dad. He was like your brother, and the instant connection you two had will forever be in my heart.

To Paul Diaz, Dad always said you were the best son-in-law he could ever ask for. Thank you for holding his hand with me in the end, the weekly “John” visits and grocery runs, and remember his last words of “I love you” were meant for both of us.

Dad will have a direct cremation. No services will be planned.

If you were ever part of my dad’s life, I thank you from the bottom of my heart. I know he felt the love from everyone, and you made him feel like the wonderful person he was.

Thanks for being my dad and living life to the fullest. You did a great job.

Rest easy, daddy, you’re home now.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of John McGee III’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

OBITUARY: Edward ‘Ed’ Earnest Albert Kukkonen, 1944-2026

LoCO Staff / Wednesday, Feb. 4 @ 6:56 a.m. / Obits

Edward “Ed” Earnest Albert Kukkonen, age 81, of Arcata, passed away peacefully on January 28, 2026, surrounded by family.

Ed was born on July 3, 1944, in Hancock, Michigan, to Edward and Irene Kukkonen. After graduating high school, he proudly served in the United States Navy. Following his service, Ed made his way to Northern California, eventually settling in Eureka, where he built a life grounded in hard work and family.

Ed took great pride in his work as a forklift operator, beginning at Cal Pacific and later at Louisiana Pacific and Britt Lumber. It was while working at Cal Pacific that he met the love of his life, Charlene Petersen (Wright). They were married in September of 1977 and shared many years together filled with dedication, partnership and love.

Ed found happiness in simple, meaningful things like spending time with friends and family, and working around his property in Willow Creek. Above all, he cherished time with his grandchildren. Whether it was hunting, cutting firewood, attending baseball games and gymnastics meets, or at the drag strip. Ed was happiest when surrounded by his grandkids and being part of their lives.

Ed is survived by his beloved wife, Charlene Kukkonen; his children Kenneth Petersen, Karen (Troy) Clower, and Kim (Ken) Keasey; his sister Peggy (John) Pulkkinen; brothers Richard Kukkonen and Robert (Barbara) Kukkonen; his sister-in-law Vida (Mike) Lorenzen; his grandchildren Kenneth Petersen Jr., Austin (Shawna Estes) Petersen, Lane Clower, Garrett Clower, Chet Keasey, and Shelby Keasey; and his great-grandchildren Aubrey Petersen and Daytona Petersen, along with numerous nieces and nephews.

He was preceded in death by his infant son Edward Richard Kukkonen; his parents Edward and Irene Kukkonen; his sisters Esther (Alfred) Nanerville and Sandra Aittama; his father-in-law Charles “Les” Wright; mother-in-law Evelyne Wright; brother-in-law Chuck Wright; and his loyal dog, Peaches.

Our family would like to extend heartfelt thanks to Joe and Crystal at Eureka Rehabilitation, the compassionate staff at Sequoia Springs, Redwood Memorial Hospital and Larry Keasey for their kindness, care, and support during Dad’s final days.

In lieu of flowers, donations may be made to the Alzheimer’s Association, P.O. Box 2542, McKinleyville, CA 95519.

###

The obituary above was submitted on behalf of Ed Kukkonen’s family. The Lost Coast Outpost runs obituaries of Humboldt County residents at no charge. See guidelines here. Email news@lostcoastoutpost.com.

There Will Be a Prescribed Burn in the Blue Lake/Korbel Area Tomorrow, and You’re Probably Going to See Smoke

LoCO Staff / Tuesday, Feb. 3 @ 5:01 p.m. / Non-Emergencies

Burn Dog reporting for duty. Photo: HCPBA.

From the Humboldt County Prescribed Burn Association:

On Wednesday, February 4th, the Humboldt County Prescribed Burn Association will be assisting a local rancher with a prescribed burn in the Korbel/Blue Lake area. We will be broadcast burning patches of bramble and woody shrubs to maintain open grasslands and increase forage value for livestock and wildlife. Smoke may be visible from Blue Lake and Highway 299.

All plans and dates are subject to change or cancellation depending on weather conditions, resource availability, air quality, regional wildfire activity, and other factors.

All of our burns are carefully conducted by a diverse mix of community members, prescribed fire practitioners, and fire professionals in accordance with CAL FIRE and North Coast Unified Air Quality Management District regulations. Thank you for supporting community burning!

The Kinetics Lab Has a New Location, and This is Your Chance to Lend a Hand

Dezmond Remington / Tuesday, Feb. 3 @ 4:25 p.m. / Kinetic Sculpture Racing

Some of the lab’s artifacts hanging in their Creamery District location. By Dezmond Remington.

PREVIOUSLY

Although the Kinetic Sculpture Lab won’t be the same place it has been for the last 30-odd years, they’re still sticking around — and if you want to get up close and personal with the art, you’ll have a shot soon.

The lab is moving into a warehouse at 1680 Samoa Boulevard, about half a mile from the old spot in the Creamery District. The former location is packed with sculptures and tools, and the lab’s small staff won’t be able to move all of that by themselves. The lab needs volunteers (preferably about 30 of them) for a few hours on Feb. 14 and 15 to move items to the new location, as well as people to help clean up the new warehouse on Feb. 7.

They’re also looking for people with trucks and trailers to help move everything.

Kinetic Lab contributor and Kinetic Sculpture Race competitor Malia Matsumoto told the Outpost that many of the teams who were building sculptures in the lab have moved their stuff out, so the main things left to move is lab property: lots of tools and decades-old machines, some of them floating in the rafters. Though they’re bulky, she said they’re not heavy.

Matsumoto said the lab will be able to stay in the new spot for at least one year. Matsumoto said she wants to use that time to figure out the lab’s future, perhaps becoming a nonprofit. Five racing teams are moving into the lab, and they’ll have the space to host more teams in the new place than they could in the old.

“We figure, the more the merrier!” Matsumoto said. “Thirty people doing one hour of work is much more fun than one person doing 30 hours of work. Just like Kinetics, many hands make light work.”

Go here to sign up.