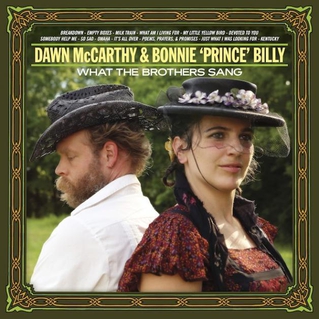

What the Brothers Sang, Dawn McCarthy & Bonnie “Prince” Billy (Drag City)

The last time Will Oldham’s nom de plume/alter ego Bonnie “Prince” Billy collaborated with Faun Fables’ Dawn McCarthy for a full-length recording was BPB’s angelic 2006 Icelandic record The Letting Go. It combined a pared-down band with lush, complex orchestrations (arranged by Nico Muhly), and McCarthy’s vocal contributions gave the album a Gaelic-Appalachian edge. The subsequent tour, consisting of Faun Fables opening each nightly set fortunately twisted its way through Humboldt County in November 2006, delivering one of the most memorable musical performances (at least from this reviewer’s perspective) at the intimate Synapsis space in Eureka.

Since then, the Bonnie “Prince” Billy persona took on different line-ups, apart from guitar stalwart Emmett Kelly, with a string of recordings, exploring the varied dark terrains, subtle sonic changes and occasional hootenannies of Oldham’s mind. So it comes as a surprise that McCarthy and Oldham have collaborated on their first full-length in six odd years, while designing the collaboration around songs initially sung by the harmonic titan duo of The Everly Brothers. What the Brothers Sang serves as a tribute to the Southern-based brother-singing duo while also trying to reshape arrangements and orchestrations from their originals, stretching towards something unique.

What The Brothers Sang Promo from lara miranda on Vimeo.

Even though a numerous and eclectic body of musicians/bands have covered Everly Brothers songs, including Linda Rondstadt, Memphis garage band, Reigning Sound, Nick Lowe and Dave Edmunds (a bonus four-song EP was originally released as a bonus 7” accompanying the vinyl release of Rockpile’s ’80 self-titled debut), and, most recently, Robert Plant and Alison Krauss, no one has had the nerve to dedicate an entire full-length to The Everly Brothers’ work. McCarthy and Oldham have wisely sidestepped many of their best known ‘50s hits, like “When Will I Be Loved,” “Wake Up Little Susie” and “Bye Bye Love.” In turn, for the most part, McCarthy and Oldham have concentrated on the late ‘60s and early ‘70s period of The Everly Brothers’ canon.

Aside from the aforementioned guitarist-vocalist, Emmett Kelly, McCarthy and Oldham assembled some of the most extinguished group of Nashville session players, including drummer Kenny Malone, bassist Dave Roe, keyboardist Bobby Wood and pedal steel player Dan Dugmore. Collectively, they’ve recorded with some of country music’s royal stable, including George Jones, Johnny Cash, Dolly Parton, Charlie Louvin, Dwight Yoakum and Charley Pride, to name a few. Additionally, they corralled younger Nashville producer Dave Ferguson, who’s best known for his engineering work on the latter-day Johnny Cash album “American Recordings” and lending his production talents to the likes of John Prine and The Del McCoury Band. Ferguson keeps the sound simple, warm and clean, while the accompaniment adds subtle depth to McCarthy and Oldham’s arrangements without overwhelming the vocals.

McCarthy and Oldham successfully interweave their own vocal harmonies in exposing and lifting many of The Everly Brothers lost gems, including Kris Kristofferson’s pre-alt. country “Breakdown,” recorded for their ’72 album, Stories We Could Tell, the delicate chamber folk-pop of “Empty Boxes,” penned by The Beau Brummels’ Ron Elliott, and two of Don Everly’s late ‘60s compositions, the British Folk-influenced “My Little Yellow Bird” and the mysterious “Omaha.”

However, the pair can’t really match the shimmering psychedelic pop original of Carole King and Gerry Goffin’s “You’re Just What I Was Looking For,” originally recorded by The Everlys in ’67, yet remained unreleased until ’80. (Of course, it doesn’t hurt to have one of the songwriters, Carole King, to sing backup on the original.) For two ’58 classics, “Devoted to You,” written by the legendary songwriting husband-wife duo Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, and Karl Davis’ aching “Kentucky,” recorded in ’58, McCarthy and Oldham perhaps illustrates how difficult it is to deconstruct perfection. And, at least in these instances, it simply can’t be done, yet.

What the Brothers Sang’s well-thought-out selection itself serves as an excellent tribute and entry to the brilliant work of The Everly Brothers. McCarthy and Oldham valiantly put their sincere, full effort in tackling the complexities of the brothers’ execution and arrangement, and they often hit the mark, with enough of a distinction from its original, especially when they seem to tap their initial chemistry that transpired on their The Letting Go vocal collaboration. More importantly, perhaps, it urges the listener to seek the originals, to discover (or rediscover) the magic of The Everly Brothers, as they took their unique, Southern-based harmonies and evolved and experimented, often with results akin to Brian Wilson’s and The Beatles’ more challenging work. At the crest of two tumultuous decades, The Everly Brothers found themselves without the critical and popular attention now afforded to those whom once were hungry mentors of their artistry.

(“On the Record” is KHSU Music Director Mark Shikuma’s occasional column about new records.)

CLICK TO MANAGE