Katherine Rominger’s voice was low, her words catching in the tangled memories of her childhood. “My mom had locked us outside and we could hear her screaming,” she said in a recent interview.

For years, Rominger and her younger brothers were witness to the abuse her mother faced from her partner. She was 8, she thinks, the first time she witnessed the violence. “Me and my two brothers we were locked out of the house so he could beat her in private. We knew what was going on and we wanted to get back in so we could protect her.”

Rominger found a place where she could look through a window. “I could see my mom cowering next to a dresser and he — he put his foot through a TV about four inches away from my mom’s face. I thought he was going to put it through her face. I didn’t think he would miss,” she said.

“He” has no name when Rominger describes her childhood. There’s usually just a pronoun and the raspy tear of her voice pulling back from the word.

After witnessing her mother’s abuse, Rominger herself became the victim of an abusive relationship. “That chain is hard to break,” she said. “You think it is OK for you to accept it… . [My mom] stayed with that man for 13 years until I was 15. She was still in that relationship when I got into a relationship with Josh.”

When Rominger was just 13, she started dating Josh K., a man who later became her husband. “I moved in with him when I was 14 because I was running from my home life,” she said.

Seeing your parents or caretakers engage in domestic violence is the strongest risk factor for passing that behavior on to the next generation, according to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence.

“[Josh] was extremely controlling before I moved in with him to the point he would punch holes in the wall,” Rominger explained. “I thought that was because he wanted to protect me. … I didn’t know any better.”

What she didn’t know then is that attempts to dominate are a common precursor to domestic abuse. Now she recognizes that the violence she experienced from Josh K. began as he attempted to force her to behave in ways he deemed acceptable. “It started by controlling,” she said. “If I smiled at someone in the grocery store, he would yell at me and tell me I was a whore. I wasn’t allowed to wear makeup or curl my hair. I wasn’t allowed to be feminine.”

Though there is no one way domestic violence occurs, abusers often engage in insults and attempts to isolate the victim from friends and family. They also use intimidation and threats of violence to loved ones to control their partners. (See below for signs of domestic abuse and numbers to call for help.)

Josh liked “making me cower,” Rominger explained. “He would get over the top of me and act like he was going to hit me.” That lasted a couple months, she said. When she was pregnant with their first child, he progressed to threatening other people if she didn’t do what he wanted. “He would say my actions were going to get other people hurt,” she explained. “I took that pressure on. I kinda shouldered it. He also said he would kill himself — he was physical with himself if I didn’t act appropriately.”

Eventually, the threats got more violent. “Then,” she said, “if I went to ask if I could go watch TV with someone else, he would get a knife out and threaten to kill them.”

He began escalating the attempts to make her feel humiliated. “He began kicking me in the behind as I would go backup the stairs. It didn’t really hurt. It just made me feel small.”

The violence increased. “It started out with little bits of shoving and taking my power away, then [progressed] to open hand slaps,” she said.

Eventually, she left and hid from him. Describing how he eventually caught her, Rominger’s voice sounded detached, almost dull except for occasional cracks. “When I was running, I hid from Josh for about a month. The one time he did catch me, someone had to bring out a shotgun to get him to let go of my throat,” she said. “They had to pull a gun on him to get him to let go of me. That was in front of the Honeydew store.”

When he got hold of her again, she said, it was terrible. “And then when he found me, he drug me up the road by my hair.”

She fought back. “I hit him in the face with a Maglight because I was scared.” Eventually, she made it home and called to her mom for help. Her mom sent the sheriff.

And Rominger was arrested.

“Because I had left a mark on his face, I went to jail,” she said. Rominger doesn’t blame the officer. “There wasn’t a way for the sheriff to know what was happening. I didn’t show him my bruising. I didn’t do that because I knew that domestic violence charges don’t go very far. It would have been his first [charge] and he would have walked. Then it would have been revenge. I knew he couldn’t get me in jail.” She felt that he would kill her if she didn’t somehow get away. Jail seemed safe to her.

“It is a very difficult call for [law enforcement] to make,” said Brenda Bishop, executive director of Humboldt Domestic Violence Services. “Lots of times they don’t get the full story. Police say those calls are some of the worst they get.” In Eureka, there is an effort made to get a client advocate to ride along with police. These advocates can help victims get out of an abusive relationship.

Bishop explained that victims in a case with a client advocate are more likely to follow through with leaving the abuser, more likely to fill out restraining orders, and more likely to follow through on making charges against the abuser.

Rominger wasn’t safe in jail for long. “He bailed me out…and made sure I went home with him,” she said. Why would she go home with him? She still feels like she didn’t have any good choices. “I didn’t have any place stable to go. It was either that or go to an abusive home with my mother.”

Also, like many victims, Rominger thought he would stop the abuse. “I was pretty headstrong,” she explained. “I thought I could change him. I really thought I could change him. I thought if someone loved him through it all, he would change.”

The reality is that abusers have trouble stopping. In one study, 62 percent of abusers arrested were rearrested within two years of their release.

Lt. Steve Knight of the Humboldt County Sheriff’s Office explained that it isn’t uncommon for the abuser to feel badly afterwards. The abuser might apologize, he said, or send flowers, but when “another triggering mechanism occurs, violence results.”

“It often doesn’t get better with time,” Knight explained. “It escalates.” Knight points out that law enforcement does have tools to help the victims. There are emergency protective orders that buy the person five days, giving the victim time to get temporary restraining orders. “No actual injury is required,” he said. “Only a slight physical contact out of anger or disrespect is needed.”

Domestic abuse cases made up a little over 7 percent of all arrests and bookings in Humboldt County last year. More than 750 people were taken in on one or more domestic violence charges in 2013, for an average of more than two per day, according to online information from the Humboldt County jail (gathered from LoCO’s Booked by Hank Sims). That number is up from 679 booked in 2012. (A sampling of numbers taken on April 8 has 32 men and four women being held in jail on those charges.) These kinds of numbers require a substantial investment of money and manpower by local law enforcement.

“Abusers many times come back [to the jail] three or four times,” Knight said. With that kind of violence reoccurring in the victims’ lives, why don’t they leave? “Sometimes it is not as easy for the victim to leave as it would seem,” Knight said, explaining that the abuser often has control over the family’s income and sometimes threatens to harm children or pets if the victim leaves.

Bishop agreed. Women’s shelters will take children but usually not animals, she said. “Survivors often won’t leave if they have to leave their animals behind.” Bishop explained that Humboldt Domestic Violence Services has a unusual program — the Jennifer Bushnell Memorial Fund. Named for the daughter of Southern Humboldt resident Angie Gillam, this fund provides money to shelter the victim’s animals while the victim stays in a safe place or domestic violence shelter.

Gillam’s daughter, also from Southern Humboldt, was shot down in a 2007 domestic violence incident in Flag City, Calif. Gillam believes that her daughter might have left her abuser in time if she had known that her dog Gucci would be safe.

Gillam explained that family members often feel helpless to intervene. “You feel like a worthless parent because you can’t protect your child,” she said.

Now she accompanies a video on domestic violence to school presentations. Kids entering high school are particularly open to breaking away from domestic violence patterns if approached correctly, she explained. The pain of watching the graphic video is offset by her sense of doing something to help. “It is kinda hard to watch Jennifer being shot seven times in one day,” she said quietly. But, she added, “If we can save one life, then it is worth it.”

Bishop said there’s a limited number of beds for survivors of domestic abuse in Humboldt County. The exact number is “kind of tricky,” she said, because there are lots of private ones provided by churches, and WISH in Southern Humboldt also provides shelter for domestic abuse victims. But Bishop’s organization has less than 12 emergency shelter beds. “We’re looking into purchasing another shelter,” she said. “We have so much demand.”

Rominger, who was only 19 at the time she was arrested, didn’t even think about going to a shelter. She thought she had to go back with her partner to their remote property in the coastal hills of Humboldt. But within a few weeks, Josh beat her so badly she bears the damage to this day. At one point in that assault, she said,

“I take off running. He grabbed me by the pony tail and dropped me to the ground. I was on my knees begging for forgiveness. He drop-kicked me in the face with boots on. The metal piece on the boot ripped the skin and I almost lost my eye.

“He drug me in the house up the steps and pulling me by hair — up the stairs bouncing on my behind. That is how I have hip problems now. When he got me in the bedroom, he made me strip naked and he beat me with a 308 assault riffle for about four hours.”

He would alternate yelling and beating.

“I had bruises on the back of my head, my tailbone, all over. My hair was matted with blood. Somehow after he beat me for hours, I found a soft spot in him and begged him to take me to the hospital.

“He put me in the bathtub and tried to scrub off the blood and wash the bruises out. He tore the skin under my eye more. After that he realized the bruising was permanent.

“After hours of me begging, telling him I was dying, he took me to the hospital.”

On the way to the hospital, he created a scenario to explain what had happened to her. “I told the sheriff I was gang beat by a bunch of girls,” Rominger said. “They believed that story.”

Neither medical professionals nor law enforcement made Josh leave her alone while she told her story, she said. He was there watching every word she spoke. According to her, he helped tell the story to law enforcement. “Basically he told the sheriff I brought it on myself by mouthing off” to the non-existent girls.

Medical personnel in Garberville put stitches underneath her eye at the top of her cheekbone. She still has a scar. She had to be taken by ambulance to Fortuna for severe head injuries.

“Josh refused to let me ride and he drove me at this time,” she said.

He was still angry with her and on the way from one hospital to the next, he began beating her more.

“[He] slammed my head into the dashboard and broke open the stitches … . He stopped at the Eel River bridge and was going to throw me off and I fought him off. Middle of the 101.. . It was night. It was late, no traffic.”

When she got to Redwood Memorial Hospital they had to restitch her face, she said. They told her she had severe head trauma. “One more hit and I could have died,” she said.

“The swelling was so bad that my brother and my dad did not recognize me,” she said. “My kids would not come to me. They just screamed and I was still expected to cook and clean. If I tried to nap, he would punch me in the head… . He knew that I very possibly could die any time he punched me in the head.”

After that, she said, she wasn’t “allowed” to be alone. “When he went to the city, I had to go with him.”

Several times, she said, he told here he already knew where he was going to bury her body. One day, when they went to the city, “I thought he was still sleeping. I went upstairs to the lady whose house we were staying in. I called my mom and said I needed help.”

Then she heard a noise and turned around to see Josh standing behind her. He had woken up. “I knew I was dead if I didn’t get out of there,” she said. He made her pack up to leave, but before they got out of the house, the sheriff showed up. “I told the sheriff that I wouldn’t talk unless he put me in his car and got me out of there,” she said.

Once in the sheriff’s custody, with some pressure, she told law enforcement about a murder committed by Josh. He was arrested and she testified against him. He’s still in jail.

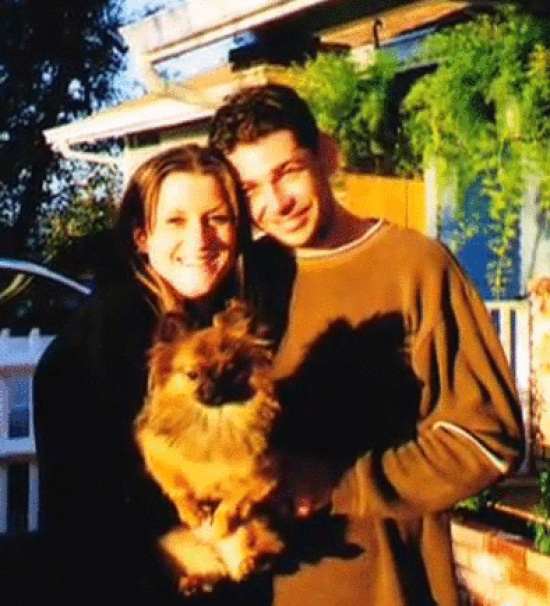

Rominger is recovering. She’s remarried, gone to school, and her children are with her. “I have my kids; I’ve got a dog,” she said. “Basically, I just turned it around. I turned the negativity into the power to feed my success.”

Rominger today. [Photo provided by her.]

Rominger today. [Photo provided by her.]

“A lot of my healing came from working on domestic violence projects,” she explained. “I felt like my story wouldn’t be a waste — like I could save someone else with my words.” She speaks the screams of her mother and herself.

This evening, Rominger will be talking at the Candlelight Vigil at the Humboldt Bay Aquatic Center. The vigil begins at 6 p.m.

“Life is a lot better now,” she explained in a firm voice. “There is life after domestic violence.”

Humboldt’s Domestic Violence Services 24 Hour Crisis and Support Line can be reached at 707 443 6042 or 1 (866) 668-6543

-

Telling you that you can never do anything right

-

Showing jealousy of your friends and time spent away

-

Keeping you or discouraging you from seeing friends or family members

-

Embarrassing or shaming you with put-downs

-

Controlling every penny spent in the household

-

Taking your money or refusing to give you money for expenses

-

Looking at you or acting in ways that scare you

-

Controlling who you see, where you go, or what you do

-

Preventing you from making your own decisions

-

Telling you that you are a bad parent or threatening to harm or take away your children

-

Preventing you from working or attending school

-

Destroying your property or threatening to hurt or kill your pets

-

Intimidating you with guns, knives or other weapons

-

Pressuring you to have sex when you don’t want to or do things sexually you’re not comfortable with

-

Pressuring you to use drugs or alcohol

CLICK TO MANAGE