Close-up image of a New Zealand mud snail. Photo by Dan L. Gustafson, courtesy California Dept. of Fish & Wildlife.

Invasive New Zealand mud snails have been found on the campus of Humboldt State University. If you think that’s not a big deal, keep reading.

That’s a picture of one, on the right. Cute snail, right? People tend to find tiny animals adorable, and the aquatic New Zealand mud snail is itty-bitty — on average about five millimeters long, fully grown. (Here’s a picture of a bunch of ‘em scattered around a dime, for scale.)

But these mini gastropods can cause big problems. They’re native to New Zealand, as the name implies, but unfortunately they’ve made their way here to the U.S., where they’ve wrought havoc on a variety of waterways.

These suckers represent the worst kind of invasive species. They reproduce asexually (usually producing female clones); each one is born with developing embryos already inside of them; and after maturing to the tender age of three months, a female can produce 230 new females every year, according to the California Department of Fish & Wildlife. A single snail and its offspring can spawn more than 2.7 billion snails within four years.

You start to see the problem.

As their populations grow more dense the snails start to choke out native insects, which, here in California, serve as food for trout and salmon.

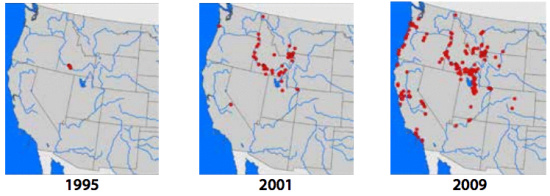

Their first stateside appearance was in Idaho in 1987, and they’ve been spreading steadily, virus-like, ever since:

These maps show the spread of the New Zealand mud snail from 1995 to 2009 in the western U.S. New Zealand mudsnails have recently been found in parts of the Great Lakes region. (Maps courtesy of Amy Benson, U.S. Geological Survey.)

Here’s an animated map showing how they’ve multiplied.

Oh, and also: Once they appear somewhere they can’t be eradicated.

They’ve been on the North Coast for some time now. (See this North Coast Journal story from 2011.) They’re in Big Lagoon, Stone Lagoon, Freshwater Lagoon and Redwood Creek, as well as the Klamath River in Del Norte County. But their appearance in HSU’s College Creek may prove especially problematic.

Jonathan Hollis, a fisheries biology grad student, was among a group of grad students who spotted them. “I just happened to notice an extraordinary number of the things blanketing that short stretch of the creek there next to the soccer field,” he said via email. “There’s so many you can actually see them from the walkway.”

He and his fellow students collected a few and took them into the lab to inspect under a dissecting scope. They quickly recognized the little buggers.

“That’s when we notified the Dept. of Fish and Wildlife and the city of Arcata,” Hollis said. “From there it moved up the chain of command pretty quickly as I understand.”

Daren Ward, an assistant professor in the Department of Fisheries Biology, said he couldn’t possibly count how many there are in the little creek. “Thousands and thousands,” he said. And there’s something different about College Creek.

“Everywhere else I know of, [the snails] seem to be limited to little estuaries or lagoons,” Ward said. “Here they’re up in a stream in pure freshwater. … The worry is that that will serve as place where mud snails can spread to other streams.”

Mud snails spread easily by attaching to boots, boats, clothing and gear of all types, often going unnoticed because of their diminutive size. “As a result,” the state Fish & Wildlife Department notes, “they are commonly transported by unsuspecting anglers, boaters, other water recreationists, or even wildlife, including harvested fish.”

So what can be done?

“That’s a good question,” Ward said. “I wish I knew how to get rid of them. The best we can do is try not to spread them around. If we can avoid moving them around then we can keep them contained.”

Fish & Game has a brochure explaining the best techniques to avoid spreading the clutchy critters. Here’s the pdf. But we’ll also reproduce the pertinent advice below:

- If possible, keep several changes of field gear for use in different bodies of water.

- Clean all gear before leaving a site, scrubbing with a stiff-bristled scrub brush and rinsing with water, preferably high-pressure. This is often the simplest and most effective for prevention.

- Inspect gear before it is packed for transport. Visible traces of sand, mud, gravel, and plant fragments are signs that gear has not been properly cleaned and mud snails may have been retained.

- Select a treatment method in addition to scrubbing and rinsing if mud snails are present or suspected to be present.

For more information, visit the CDFW webpage about the mud snails.

CLICK TO MANAGE