Zoologist, writer, eco-tour owner, scuba diving instructor and top marijuana defense lawyer Robert Cogen (right) works with his assistant putting together complicated stained glass creations in his Eureka studio. [Photos by Kym Kemp.]

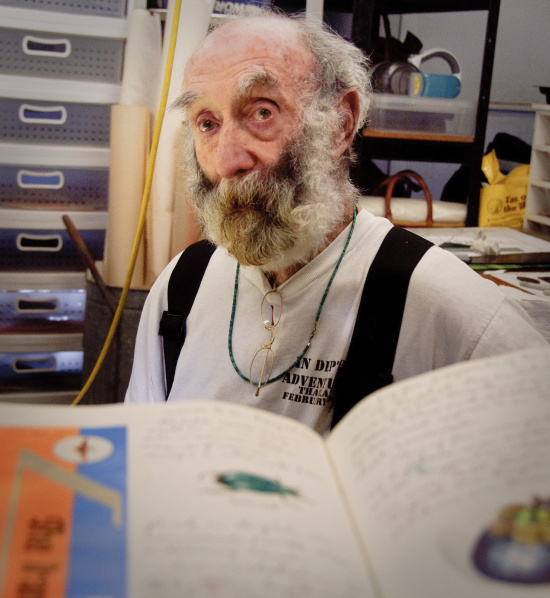

Slender, with a body twisted like a weak vine around a strong inner core of determination, Eureka resident Robert Cogen inches his way from his home to a studio in the backyard. One of his hands grips a cane while the other curls at his side. Cogen, nearly 80 years old and once a nationally known marijuana defense attorney, walks with difficulty following a stroke, but inside his studio he creates glowing stained glass panels as he has for over 30 years.

A bird snatches a fish from a North Coast river. The idea for the stained glass creation came from a fishing trip where an osprey successfully captured dinner and artist Robert Cogen didn’t.

He used to do the work entirely by himself. Now he designs the panels and an assistant helps him with aspects which are difficult due to his weak arm. Many of his images come from the North Coast. Others come from his travels.

This image under creation is of a favorite coastline in Thailand. Glass pieces are assembled and numbered. Then copper strips are applied to each piece before the segments are soldered together.

One wall of Cogen’s studio holds thin sections of colored glass waiting to be created into jeweled art in the future. Another wall is lined with journals documenting his past.

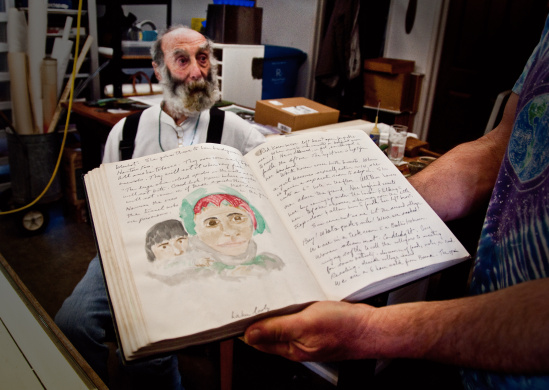

Cogen’s assistant randomly opens one of the journals to a page Cogen illustrated and wrote decades ago.

Cogen’s assistant randomly opens one of the journals to a page Cogen illustrated and wrote decades ago.

His past is colorful. Cogen, who claims he won 94% of his cases, was instrumental in introducing the species defense for clients accused of marijuana offenses. The species defense relied on the lack of knowledge about cannabis prevalent when laws against marijuana use were written. Most states only declared Cannabis Sativa illegal, but Cogen, who had a degree in science, had botanists testify in a Humboldt County courtroom that Cannabis Indica was another species and thus not illegal. The judge ruled in his favor. The ruling caused an uproar and the story was reported nationally.

In describing this aspect of his life, Cogen said, “I’m surprised that we haven’t legalized [pot] yet… . I feel like if and when it does get legalized, I’ll have played a small part in that.”

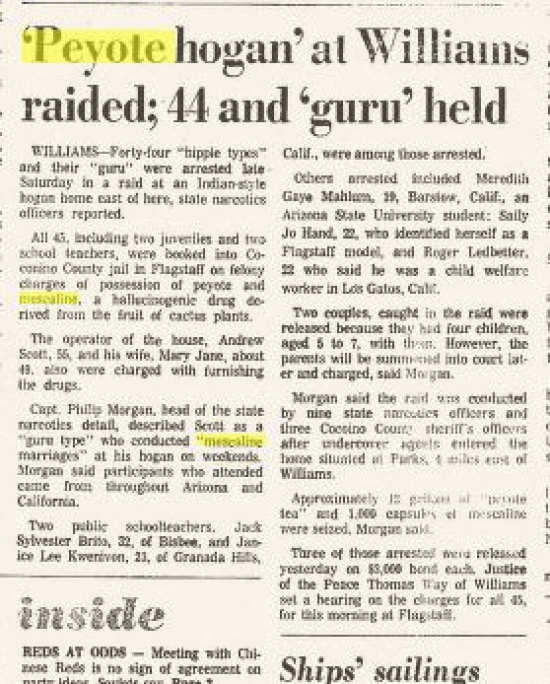

Cogen’s most famous case, however, was tried in Arizona. There, in 1969, nearly 50 people were arrested in a raid on a Native American ceremony. They were charged with possession of peyote and mescaline. Several of those arrested contacted Cogen at his law offices in Southern California. Cogen and another attorney defended them for free on religious grounds. “We wanted a binding decision that would last forever,” Cogen explained.

Eventually, Cogen said, “The Arizona Court of Appeals handed down a unanimous decision in our favor… . Arizona then appealed to the Supreme Court [and] the U.S. Supreme Court basically sent them a post card saying, ‘It’s over. You lose.’”

Robert Cogen successfully defended several of those arrested for taking part in a Native American ceremony that involved peyote. Here, The Arizona Republic reported that “forty-four ‘hippie types’ and their ‘guru’ were arrested in the incident.”

After laboriously crossing the yard, Cogen sits down in his studio among the different sections of his life. A plaque and his t-shirt bear the name of In Depth Adventures, an eco-tourism company he once owned. A photo shows him with his partner in their scuba diving gear. Portraits of animals and people he encountered in his travels adorn pages of the dozens of thick journals that occupy four or five shelves on one wall. Each of the animal drawings show the intimate knowledge of a trained zoologist. He speaks about books he has written or is writing.

Cogen crumples one impossibly furry brow above a sunken eye as he skeptically regards his assistant reading from his journal.

As his assistant lays out the numbered pieces of glass on the long lightboard, they form a glowing line off into the distance. Cogen watches. He designed the image coming to life. He chose the colored glass and helped cut the pieces, but now he watches as another’s strong hands lay each colored section carefully, bringing order out of the different shapes.

A piece that has taken 18 months of work so far still has many steps to go before it is finished.

Cogen has help, but it is still his vision that brings the art to life. He loved the bay that his latest piece depicts. “It was one of the most beautiful places I’ve ever been and it has some of the most beautiful diving,” he said.

As his assistant settles the last pieces in place, Cogen sits quietly in the late afternoon light coming through the open studio door. He has laid out the sections of his life this day, examined them, and set them where they belong in the timeline of his life. The piece isn’t finished but much of the hard work is done.

CLICK TO MANAGE