[NOTE: This is the first in a new series called “I Don’t Believe You” in which unbelievable claims are treated as, well, unbelievable. If you’ve heard or read something locally that left you skeptically curious, email your segment pitch to mike@khum.com and put “I Don’t Believe You” in the subject header.]

The Unbelievable Claim

An environmental group claims that a lily consortium that just won a state award for pesticide reduction is actually increasing its pesticide use.

That’s not believable, right? That makes no sense.

Greg King, the leveler of this unbelievable claim, is the executive director of the Siskiyou Land Conservancy. He told KHUM: “In the 14 years I’ve been working this issue, you know, the pesticide inundation up at Smith River plains surrounding the estuary, I’ve never seen anything this egregiously wrong.”

The Questions at Issue

1. Was the state award, in fact, intended to honor those who have reduced their pesticide usage?

2. If so, has the recipient of the award, far from reducing its pesticide usage, actually increased it?

Facts in Evidence

The Easter Lily Research Foundation is the research & development arm for the major bulb growers in lower Smith River watershed, which produces at least 90 percent of U.S. easter lilies. The easter lily is big business. It’s the fourth biggest potted-plant crop in the country.

Last week, the California Department of Pesticide Regulation bestowed upon the foundation its Integrated Pest Management Innovator award, which the department calls “its highest honor.”

What is this award? What is it meant to honor?

In a press release on this year’s crop of IPMI honorees, the department says that three such honorees were chosen “for their work in finding innovative ways to solve pest problems while reducing the use of chemical pesticides.” Elsewhere, the department says the award is given to those who promote “reduced-risk pest management practices” and “favor least-hazardous pest management.”

The Claimant’s Case

Greg King, speaking for the Siskiyou Land Conservancy, writes:

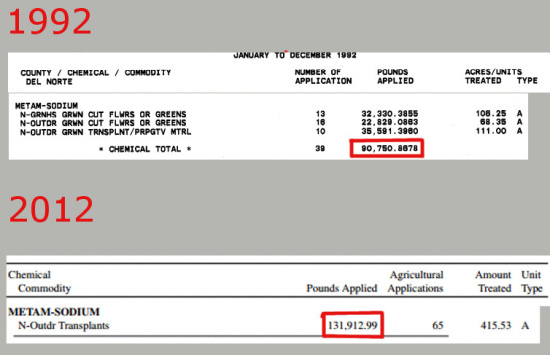

Easter lily pesticide use increased from about 180,000 pounds in 1992 to 297,000 pounds in 2012 (the latest year that numbers are available), an increase of 65 percent …. Moreover, these numbers come from CDPR’s own web site.

These numbers are correct. In particular, the 2012 CDPR data below shows a marked increase since 1992 of at least one particular pesticide called metam sodium, which King says was “the chemical that, in 1991, spilled into the Sacramento River, killing everything for 40 stream miles before diluting in Lake Shasta.”

Metam sodium is not the only pesticide of concern. A National Marine Fisheries Service report from Sept. 2014 report looking at strategies to recover coho salmon populations around the region takes a dim view of current lily farming practices along the Smith.

Of particular concern is the lily farming that occurs in the Lower Smith River. Recent testing in the lower Smith River has revealed copper concentrations that may have acute toxic effects and impair olfaction and reproduction of coho salmon (North Coast Smith River Population Final SONCC Coho Recovery Plan 15-14 2014 Regional Water Quality Control Board [NCRWQCB] 2011). Copper is a component in a number of pesticides and fungicides used on lily fields. The current level of chemical contamination is a high risk for juvenile salmonids.

Also, if we understand correctly, applying copper-based fungicide to a field will turn it blue-green, at least on Google Earth. So there’s that.

Sidenote: if you check out historical images from Google Earth, it looks like they rotate cows onto some of these same pastures.

If the Easter Lily Research Foundation, King concludes, has come up with new “reduced-risk” farming methods, they’re not deploying them. At oral argument, below, he said:

If in fact, they’re working on reducing pesticides, their own numbers don’t show that. The numbers show the opposite. Lily growers need to held accountable for the amount of pesticides used in this watershed … Giving them an award is rewarding this behavior that has led to the toxification of one of the most important salmonid streams on the west coast of the United States.

The Case for the Defense

What the California Department of Pesticide Reduction says:

Easter Lily Research Foundation (ELRF): This organization has a research facility dedicated to finding new ways to control pests and diseases of Easter lilies. On its 1,800 acres of land in Del Norte County, the foundation has adopted a number of practices to reduce their pesticide use. This includes developing a strategy to tackle aphids without increasing the use of organophosphates. The organization, headquartered in Oregon, works closely with the University of California at Davis to control nematodes while reducing the use of fumigants. With the help of a USDA Specialty Crops Block Grant, the foundation is researching how to breed a new Easter lily that requires less production time, acreage, and pesticide use.

Del Norte Agriculture commissioner Jim Buckles, who nominated The Easter Lily Research Foundation for the award, spoke highly of the Easter Lily Research Foundation:

“They’re always on the lookout for using less toxic pesticides, you know; not all of them work. Pesticides are expensive to use and (critics) seem to think farmers want to use them all. They’d rather not use them but they do what they have to do to grow a crop.”

Buckles said he nominated them for their exploration into alternative pest control like adding crab shells to the growing medium, experimenting with rotations, or adding black rock to heat the soil.

Charlotte Fadipe, a spokesperson for the California Department of Pesticide Regulation, agreed that the award isn’t necessarily shackled to the actual amount of pesticides used.

The foundation has come up with ways to reduce pesticide use. It is true that the growers have not had a net reduction in pesticide use, but you cannot detract from the fact that the foundation has, over the years, come up with ways to reduce pesticide use.

When you look at what this organization does, they do use pesticides, no doubt about it. Some years it goes up, some years it goes down. We gave them the award for the research they do.

Lastly, Lee Riddle of the Easter Lily Research Foundation tells us:

I don’t know where you got your information but ELRF did not win a pesticide reduction award. I don’t think they have such an award. ELRF did win an IPM Innovators award for the work they have done over the last 40 years in integrated pest management. We have been working toward pesticide reduction by breeding superior lilies and testing many new pesticide alternatives.

Oral Argument

Greg King further presented his case to the KHUM listenership yesterday.

The Judgment

Two of the three pivotal facts of the case are not in dispute. The Easter Lily Research Foundation, an industry R&D consortium, did in fact, receive the award. The groups that make up the ELRF have, in fact, dramatically increased their pesticide usage.

That leaves the question of what the award is, in fact, intended to recognize. Charlotte Fadipe, above, argues that the award is based on the research performed by the ELRF. However, this is belied by her employer’s own literature, which talks so often of “reduced risk” and “least hazardous” pest management.

Even the final CDPR press release says: “On its 1,800 acres of land in Del Norte County, the foundation has adopted a number of practices to reduce their pesticide use.” The plain meaning of that sentence is that their pesticide use has, in fact, been reduced. Any reasonable reader would make exactly that conclusion. Precisely the opposite is true.

King may be faulted for trumping up the importance of a simple typo in both his original press release and at oral argument. Also, he repeatedly calls the award a “pesticide reduction award,” which oversimplifies its stated purpose. (Though repeated references to pesticide reduction are made in the literature, other factors in picking winners are also cited.)

Nevertheless, the unbelievable claim must be believed.

CLICK TO MANAGE