File photo.

Just how bad are the conditions at the Mental Health Branch of the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS)? It depends on whom you ask.

Case managers and other frontline staff who spoke with the Outpost on condition of anonymity say the branch is in a state of chaos, little if any better off than it was earlier this year, when a rash of departures from doctors and nurses threatened to shut down the county’s inpatient mental health facility, Sempervirens. These workers describe an environment of “unbelievable stress” and woefully inadequate patient care, problems they say stem from the authoritarian, even abusive management.

The Humboldt-Del Norte Medical Society is calling for a Grand Jury investigation due to the ongoing issues in the branch. Outpatient services, they say, are a shell of what they used to be, and management has created “a pervasive culture of bureaucratic indifference to the input of employees and the community.”

In an interview Tuesday, Barbara LaHaie, the Humboldt County Department of Health and Human Services’ assistant director of programs, acknowledged that there have been staffing shortages, particularly in the outpatient unit, that have caused long delays in patient appointments and interruptions to their continuity of care. And she said management is “very concerned” about employee morale.

“We have to do a better job of working with our staff,” she said. “We all need to be there to make things better, and I think it’s critically important that they share their concerns with us, and share their thoughts.”

There’s a chasm between the two perspectives. LaHaie suggests that the problems at the Mental Health Branch, while serious, can be solved through better communication and filling open positions with local, full-time doctors and nurses.

But staff and outside doctors say more serious measures are needed. One employee at Sempervirens told the Outpost that she recently filed a grievance with the Grand Jury. “We need subpoenas; we need to get in there; we need the line staff interviewed,” she said. “We are drowning there. It is dangerous.”

Another worker – a case manager – said hiring new doctors and nurses won’t solve the problem because they probably won’t stick around for long.

“The atmosphere is so corrosive that nobody wants to work there,” he said. “I’m not sure if they’re recruiting for nurses, but people are dropping like flies. It’s absolutely unbelievable. I really believe the state should take over.”

# # #

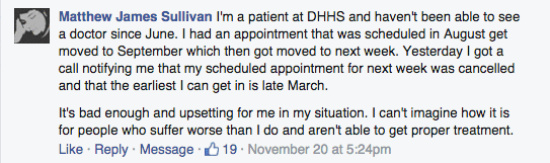

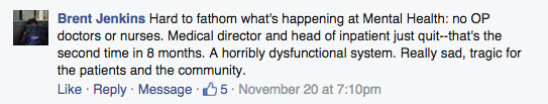

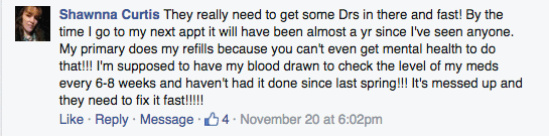

Here are a few Facebook comments the Outpost got in response to last week’s story on the Mental Health Branch:

Back in March, when the inpatient staffing shortage was threatening the very existence of Sempervirens, the county hired Traditions Behavioral Health, a Napa-based staffing firm, to fill the psychiatrist vacancies, which the firm has done in part by bringing in locum tenens, or temporary, traveling physicians.

The county is paying Traditions $3.2 million this fiscal year, and according to LaHaie four of the six physician/psychiatrist positions in the Mental Health Branch are currently filled, with another doctor offering extra help. That leaves just one position vacant. In addition, there are 1.5 physician positions being filled via telemedicine.

“Most of the rural counties [in California] are solely on telemedicine,” LaHaie said. “So we feel fortunate that we are able to provide live [doctors].”

As for nursing staff, four of the branch’s 22 psychiatric nursing positions are currently vacant – the same figure as back in March. Back then the branch had only two physician/psychiatrists, along with one telemedicine physician.

Last year the county spent $2.76 million to staff its own doctors, LaHaie said. Dr. Gary Hayes, the president, founder and owner of Traditions Behavioral Health, said via email that the current $3.2 million figure is only 10 percent more than what was planned in the county budget. And he, for one, is optimistic about success.

Traditions is advertising a full-time position in Sempervirens at an annual salary of $350,000 plus $10,000 in bonuses and a full benefit package. Full-time outpatient psychiatrists here are being offered $310,000 plus the same $10,000 in bonuses and a full benefit package.

“We have been very pleased with our response,” Hayes told the Outpost. “We have 24 new [locum tenens] doctors credentialed and the [county’s] weekend call pool is filled through March. One of our outpatient jobs has been filled with a locum but [in] the second week of December we will start a new full-time doctor who we expect with be permanent.”

What none of these figures reflect, however, is turnover. In the past two years, seven doctors in the Mental Health Branch have quit. “Two retired; three relocated; one sought other employment in the area; and one, as we know, left for personal reasons,” LaHaie said. (See our February story for more on some of those departures.)

Over the same period, 10 nurses have left the branch – five in 2014 and five to date in 2015. The case manager we spoke with, who we’ll call John, attributed the turnover to the working conditions fostered by management. “The environment they’re creating is one of intimidation and fear,” he said. “It’s unbelievable, the stress – unnecessary stress.”

The conditions described in the Facebook comments above can be traced to a doctor shortage in the outpatient facility. LaHaie explained that, since March, Traditions Behavioral Health has managed to stem the bleeding in staffing at both Sempervirens and the Crisis Stabilization Unit. But the outpatient facility is another story. Last week and this week, she said, there was a 10-day stretch in which there were no doctors available at all, which required numerous appointments to be canceled and postponed.

There was a similar doctor-less stretch a few weeks back.

This would be problematic for any medical appointment, but it’s particularly troublesome when dealing with mental health patients, who are reliant not only on their medications but also on continuity of care – a doctor who knows each patient’s history and symptoms and with whom those patients feel comfortable.

One employee told the Outpost that a number of clients have been given new prescriptions that may cause new side effects, but those patients have been unable to get back in to see a doctor because there aren’t any appointments available.

“So there were clients needing to wait, you know, four months for an appointment, which is not optimal in their care,” LaHaie acknowledged. It’s problematic, “especially for somebody who’s mentally ill.”

“The No. 1 thing we need,” said John, the case manager, “is competent doctors who know our clients.”

Traditions recently hired Dr. Raja Dutta to be the Mental Health Branch’s medical director, a position that, per California law, must be filled in order for the branch to operate. Dutta purchased a house in Trinidad with plans to stay in the area permanently, but he recently decided to decline the position.

Dr. Hayes, president of Traditions, said Dr. Dutta “plans to be an active, continuing member of the medical staff” but decided to work only part-time in Humboldt County so he could spend more time with his family in Sacramento. Employees told the Outpost that he was bullied and interfered with by Dr. Asha George, the head of the Mental Health Branch.

(George’s name was brought up by a number of employees with whom the Outpost spoke. They called her management style “incredibly controlling,” “negative” and “abusive to staff.”)

But Dr. Hayes remains optimistic, saying there are three new candidates for the medical director position, and his agency expects to select from them in January.

For the time being, LaHaie said the department is “triaging” clients, prioritizing the available appointments based on client needs.

“I would say that it is a concern of ours that patients aren’t getting timely appointments for medication support,” she said, “and we will continue to do what we can and work with TBH [Traditions Behavioral Health].”

Is the branch still in crisis?

“It really is about how you define crisis,” she said.

John, the case manager, said the situation is clear. And while he was afraid that talking to the media might get him fired, he felt compelled to do so anyway. “I don’t want to lose my job, but even my job’s not worth what’s being done to the people I’m working with,” he said. “We have to get something changed because it’s affecting people’s lives. This is wrong.”

Another employee used more colorful terminology to describe the situation: “It’s a clusterfuck of pain and misery,” she said.

Clients are currently being encouraged to come in for “same-day services,” in which they’re assessed by clinicians and if they’re in need of immediate care they get sent to the Crisis Stabilization Unit. An employee told the Outpost that this is not ideal for the patient medically or financially.

“It costs $1,500 to see somebody on the Crisis Stabilization Unit,” she said. “All these people who were stable are now a mess because they can’t get their medication.”

LaHaie said help is on the horizon. “In December we’ll have more physicians, so we’ll be able to move some people up into December appointments.”

“The other piece is we need to do,” she said, “is a better job communicating to our staff.”

George has instigated regular meetings with line staff called “Tea With Asha.” There, employees are encouraged to bring up whatever they want, LaHaie said. “I want people to feel comfortable sharing their concerns.”

She seemed genuinely troubled when the Outpost told her how scared people were to talk to a reporter and how disrespected they felt at work.

“We have to do a better job of working with our staff,” she said. “We are concerned about the morale, and we know that communication hasn’t been its best. And we will continue to reach out to staff. It’s critical that we have their input into the direction that Mental Health is going, and the day-to-day operations. We’re committed to that — whatever it takes,” she said. Then she added, “I wish I had a magic wand or, you know … .” She trailed off.

As for the doctor shortage, both LaHaie and Hayes predict that the holes will be filled with permanent, local doctors by the time Traditions’ contract expires in April.

The morale and retention of nurses and case managers may prove more difficult problems to solve, and in the meantime mental health clients in Humboldt County continue to receive care that even administrators call less than ideal. LaHaie said she and George will meet with the Humboldt-Del Norte Medical Society at their next meeting to address their concerns.

It remains to be seen if the Grand Jury will respond to calls for an official inquiry.

CLICK TO MANAGE