It’s really rather undignified, like a party girl jumping out of a cake.

— British astronomer Fred Hoyle commenting on the something-from-nothing Big Bang creation story. He had coined the phrase “Big Bang” derisively.

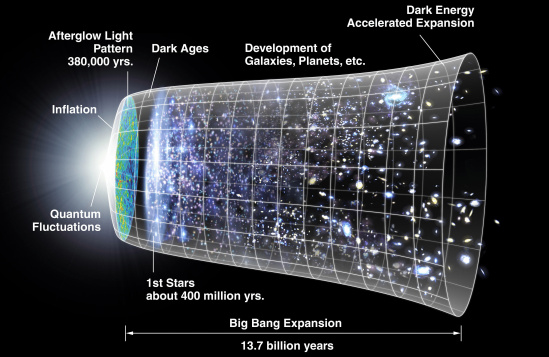

Gotta love them quantum fluctuations on the left. It’s all downhill after that. [NASA]

I’m fascinated with “nothing,” can’t stop thinking about it. Which, at the very least, has to be a lie. Whatever I think of nothing is something.

Here, I want to come at nothing from two points of view: (1) the beginning of the universe, and (2) nothing as conceived of in meditative practices, aka “emptiness.”

###

Taking the last first: one goal, perhaps the goal, of many Eastern meditation techniques — particularly Buddhist and Hindi — is the attainment of a state of empty mind, in which all sensations, all sense of self, all everything has fallen by the wayside leaving one with “pure awareness.” (The confusing word “enlightenment” is sometimes used in the West for this putative state.) Which begs the question, “How would one know?” —I’ve yet to receive a satisfying answer, despite asking many meditation “masters.”

In a nutshell, how can I be aware of what I’m not aware of?

###

My problem with mind-emptiness is analogous to the dissatisfaction expressed by most cosmologists with any theory, which asks them to conceive of a universe-from-nothing scenario, Fred Hoyle’s “Big Bang.” In this case, my naive “How do you know?” translates into “How does the latent universe know?

Know what? Know which physical constants to adopt, the constants that rule the whole shebang to give us physical laws, which govern, well, everything. There are about 26 of these constants, such as: the ratio of the masses of the proton and electron; and the fine structure constant, which relates the speed of light to the charge of the electron. As has been frequently pointed out, it seems we exist in a finely-tuned universe — muck about with any of these constants and life is impossible.

Any universe-from-nothing theory (there are many) has to play fast and loose with the definition of “nothing,” since all these physical constants are hidden under nothing’s skirt, so to speak.

Typical of such theories is genesis via “quantum fluctuations”: according to quantum theory, pairs of “virtual” particles continually pop into existence spontaneously out of “quantum foam” that is, to all intents and purposes, an empty vacuum: no matter, no radiation, no nothing. Except, of course, there has to be some underpinning — in this case, the laws of quantum mechanics—to be present, even in the absence of “stuff.” Quantum foam isn’t nothing, it’s just a bit less something.

Indeed, even discussing an origin theory requires—at least, for our limited brains—time and space for anything to happen, space being a system of spatial relations between things and time being a system of temporal relations between events. A true “nothing” is absent time and space. But if you’ve time and space, you’ve got something. Goodbye nothing.

###

We can, of course, delegate the whole problem to a Prime Mover, Logos, Cosmic Force, “god” for short. I’m no philosopher (I are an engineer), but we can probably agree (can’t we?) that god either is or isn’t part of the universe. If the latter, she/he/it can’t affect the universe, including bringing it into existence. OTOH, if god is part of the universe, we’re back to origins: whence god? (Proto-god?) If you respond that god doesn’t need a creator, I’d argue then neither does the universe. Something about chasing our tails.

###

My slippery way out is to take the “mysterian” stance (after the 1960s garage-rock group Question Mark and the Mysterians). We can’t understand this stuff by definition. At least at this point, human brains are limited; we’re confined to three-dimensional space; we evolved to survive and reproduce, and anything else is bonus. We’re limited conceptually, having no way of witnessing either our minds (analogous to the eye being unable to observe itself) or the universe from “outside.”

And even if some future Einstein came up with a completely convincing solution to either problem — mind or universe — we’re still back to my irritating question: How do we know?

CLICK TO MANAGE