El Tajin, Temple of the Niches (all photos by Barry Evans unless noted)

I never saw a ruin I didn’t love. One of the downsides of living, most of the year, north of the Rio Grande is the lack of major ruins in the US and Canada. The closest ancient ruin to the border that’s really “monumental” is, to the best of my knowledge (somebody make me wrong), La Quemada, an hour’s bumpy ride south of Zacatecas, putting it about 400 miles southwest of Laredo, Texas.

La Quemada, Zacatecas, Mexico

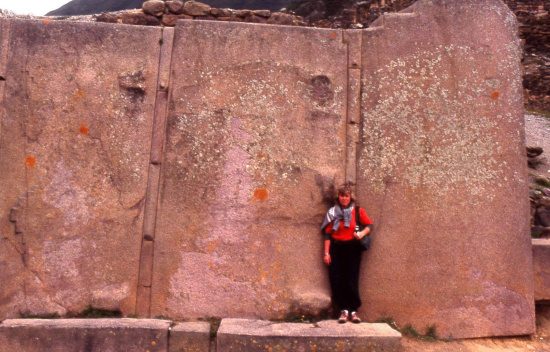

From there on, all the way down to Inca-land in Peru, it’s open-season for pyramids, ball-courts, stelae (stones bearing hieroglyphic inscriptions), temples and palaces. Some of these structures are the finest ever created. I’d never quite believed that line about the stones in Incan buildings being finished so well that “you couldn’t stick a knife between them.” That was before hiking the Inca Trail to Macchu Picchu, passing some 600-year old stone structures in pretty good state of repair finished so well that, yep, you couldn’t even stick a razor blade, let alone a knife, between them.

Ollantaytambo, Peru: not even a razor blade.

But why? Why did those people—the Olmecs (starting around 3,000 years ago), Mayans, Zapotecs, Mixtecs, and more recently (up until the time of the Spanish conquest) Aztecs, Incas—why did they go to such elaborate lengths to build huge monuments and carve stelae and huge heads that would endure to the present time? Louisa and I have a standing joke when we encounter a particular phrase, which we’ve seen on information signs in Mexico, Guatemala, Peru, Egypt, Cambodia, Vietnam—all over, in other words. The phrase is, “…believed to have been built for religious or ceremonial purposes.” This, we surmise, is archeology-talk for, “We haven’t a clue!”

El Tajin, Pyramid of the Niches before restoration, 1913

Take the ruins we spent two days exploring three weeks ago, El Tajin (“Thunderbolt” in the local Totonac language), in the state of Veracruz, Mexico. Most people don’t think of Veracruz as a tourist destination: the beaches are nothing to compare with those on the Pacific or the Caribbean and a bunch of offshore oil rigs don’t do much for the ambience. The nightlife is pretty much confined to the busy port-city of Veracruz itself, the mosquitoes can be treacherous (especially in this Zika virus era), and you have to go inland and up, to Jalapa, to find a really enticing pueblo magico (magic town) in which to hang for a few days.

Papantla, main plaza

The Totonacapan provincial capital of Papantla is an uninspiring four-hour bus ride north, up-coast, from Veracruz City. From there, it’s a 20-minute, 60 peso (three bucks) taxi ride to El Tajin.

We arrived, as is our routine when ruin-gawping, a few minutes before the official opening time, which (on both days we were there) gave us a full two hours of having the site completely to ourselves. You need at least that long to walk through the site anyway, which extends over about four square miles, half of which is accessible.

The pleasure I derive from ancient sites comes in three waves. One is intellectual—putting the ruins in context (for instance, comparing the time of the main construction phase of El Tajin, in this case, with the earliest Gothic cathedrals in France), reading every information sign, visiting the site museum, researching on-line, trying to satisfy our desire to understand the archeology. The second is appreciating the sheer beauty of some of the sites, El Tajin being a prime example. Temples, ball-courts, plazas and palaces are scattered in a lush valley between surrounding forested hills, blending harmoniously with nature.

El Tajin, main part of city

And third—the main reason to arrive early—is for the atmosphere that haunts some of these ancient places. I mean, the tingly thrill of sitting on an ancient wall or block of carved stone and letting my mind swim back through the centuries, imagining, not barren stones, but a living, breathing place, full of people, kids running about, temples painted in red ochre, shouts of market-folk selling their wares, everyone carrying something: water jugs, corn-filled straw baskets, stones to be carved, perhaps a hunter with a deer across his shoulders. Life! And that’s why we like being there without other visitors, to sit in silence and let the years between the ancient inhabitants and us fade away.

Artist’s impression of El Tajin as it once was, in the site museum

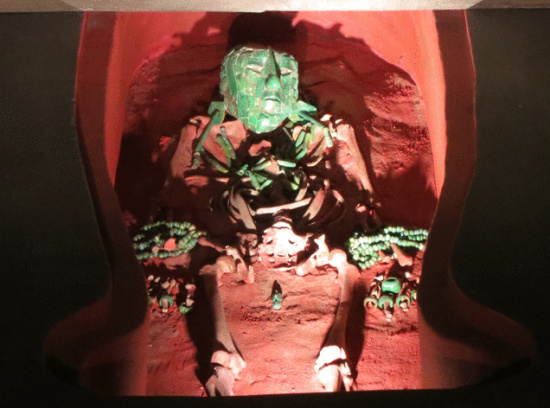

The most impressive structure at El Tajin is the Temple of the Niches, built—archeologists think!—around 900 years ago. Originally constructed with 365 square niches in seven tiers, it was topped by now-lost temple. Unlike Egypt’s 90-odd pyramids, none of the Mesoamerican pyramids were built as tombs (with the exception of King K’inich Pakal’s at Palenque. You can see a mock-up of his 7th century tomb located deep in the “Pyramid of Inscriptions” in Mexico City’s wonderful Museo Nacional de Antropología.)

Mock-up of Pakal’s tomb, Museo Nacional de Antropología

So OK, they stuck a temple on top of the Pyramid of the Niches, but it must have been next-to-impossible to access (especially for old-geezer priests), so—presumably as an afterthought—they build a super-wide staircase on one of the faces. Which, to my untutored eye, looks totally out of place. Someone must have slipped the local planning commissioner a couple of jugs of single-malt pulque.

Temple of The Niches, staircase

Getting back to my title, the Mesoamericans took their ballgame seriously, starting around 1,400 BC with the Olmecs, who apparently invented the game (Olmec means “rubber people”—the balls were made by mixing sap from the Castilla elastica tree with morning glory vines.) Archeologists have found no fewer than 20 ball-courts at El Tajin, most of them “practice” courts, but several “ceremonial” ones.

Ball-court, El Tajin

The story, confirmed in many carvings and in the writings of early Spanish observers, is that the losers were ceremonially sacrificed. Or, according so some researchers, it was the winners who were offed; sacrificing one’s life to the gods was a great honor. Whatever, at least some of the games ended in ceremonial bloodletting. One of the carved panels on the side of one of the ball-courts at El Tajin shows a victim (honoree?) being held down as his throat is about to be cut (or his head severed) with what is probably an obsidian dagger.

Loser…or winner?

Obsidian (volcanic glass), because metal came late to Mesoamerica—the earliest iron smelting only began around 850 AD, in Belize, and metal was never used extensively in the pre-Columbian New World. Obsidian from the Sierra Madre (indicative of long-distance trade routes) was probably the norm for cutting tools.

So who were these pyramid-builders, ball-players, farmers and merchants? So little is known about the 20,000-odd inhabitants of El Tajin that archeologists are reduced to “perhaps Totonac, or Huasteca, unless it was the Xapaneca people.” Whoever they were, their civilization came to its zenith during the Epi-Classic period, 900-1000, after the collapse of Teotihuacan and Xochicalco in Mexico’s central valley, and lasted until a violent cataclysm occurred around 1230.

Voladores recreating an ancient ceremony at the entrance to El Tajin

Why did they go to such lengths to build a handsome city at an indefensible site between a couple of streams in a valley Nowheresville? What was it all for?

Oh, of course, the answer is staring me in the face. It was all for religious and ceremonial purposes.

###

Barry Evans gave the best years of his life to civil engineering, and what thanks did he get? In his dotage, he travels, kayaks, meditates and writes for the Journal and the Humboldt Historian. He sucks at 8 Ball. Buy his Field Notes anthologies at any local bookstore. Please.

CLICK TO MANAGE