“We pray for the health of all Eureka,” the earnest woman said as she handed us invitations to attend Sunday services at her church. I replied with something noncommittal on the lines of, “Sounds like a worthy project,” thinking to myself, Well, it won’t do any harm, might even do some good. And then I remembered the Benson Prayer Study.

About 20 years ago, Harvard professor Herbert Benson, a cardiologist by training, decided once and for all to explore the proposition that intercessory prayer can help patients recover from surgery. The field has a long history, starting in 1873 with the efforts of English scientist and polymath Francis Galton. All previous studies prior to Benson’s, which was published in 2006, were flawed and/or inconclusive, either coming up with null results (no effect) or minor, but contradictory, indications: yes, prayer helped (a bit) or no, it worsened patients’ outcome (a bit).

With underwriting from the Templeton Foundation (which supports research at the intersection of religion and science), Benson undertook the $2.4 million “Study of the Therapeutic Effects of Intercessory Prayer (STEP), aka “The Great Prayer Experiment,” which ran from 1998 to 2005. He enrolled a total of 1,802 coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) patients at six academic medical centers. (CABG is performed on 350,000 Americans each year, many of whom suffer complications following surgery.)

Benson had the subjects randomly assigned into one of three groups, with about 600 in each. Groups 1 and 2 were told they might or might not receive prayers on their behalf—Group 1 did, Group 2 didn’t. Group 3 was told they would receive prayers, and did.

Three experienced “prayer groups” were enlisted to do the actual praying, two Catholic (a monastery and a Carmelite community) and one Protestant (a prayer ministry). They were given the patients’ first names and first letter of the last names, and asked to include the phrase “for a successful surgery with a quick, healthy recovery and no complications.” The prayers started on the day of surgery and lasted for two weeks.

Long story short: prayer seemed to make things worse. 18% of patients being prayed for (but who didn’t know it) suffered major complications, compared with 13% of un-prayed-for patients. “Regular” complications occurred in 52% of Group 1 (received prayer but didn’t know it); 51% of Group 2 (didn’t receive prayer, didn’t know it); and 59% of Group 3 (received prayer, knew it).

Perhaps (the researchers surmised) the patients who knew they were being prayed for felt additional stress (“I have to do well to justify all the prayers being said for me,” or “I’m being prayed for, I wonder if that means I’m not expected to do well.”) Or perhaps, as one of the study’s co-authors offered, “It may be impossible to disentangle the effects of study prayer from background prayer.” He explained that “background prayer” represents the additional entreaties — beyond those proffered in the study — from the patients themselves and of their friends and families. (I’m no expert on prayer, background or otherwise, but my gut tells me that any divinity smart enough to come up with DNA and quantum entanglement would be able to tell the difference.)

Or maybe the problem with the negative results is that the prayers were just too mechanical for the divinity to be moved by them. As the Christian apologist C.S. Lewis famously opined, “Simply to say prayers is not to pray, otherwise a team of properly trained parrots would serve as well as men for our experiment.”

So if we’re to take the STEP study at face value (it’s the most comprehensive one on prayer to date), the bottom line is: If you really care about someone (or some city), for god’s sake don’t pray for them.

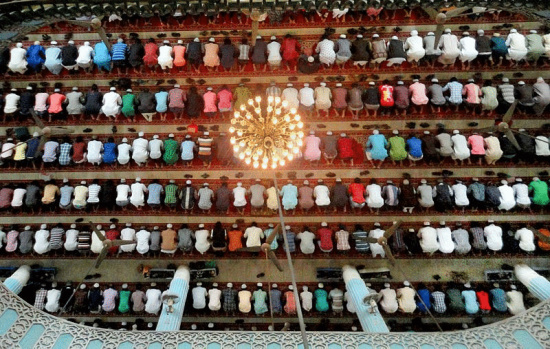

Would Muslims, like in this mosque in Bangladesh, have done any better? (Shaeekh Shuvro, Creative Commons)

FOOTNOTE ONE: The Benson study was very narrowly focused: one type of operation, supplicating only “god” as understood by Christians, with just three prayer/non-prayer groups. The study, of course, adds nothing to the question of god’s existence or of Christianity versus other faiths. Nor does it say anything about the well-documented overall health and long-life advantages of belonging to a religious community.

FOOTNOTE TWO: If the name Herbert Benson is familiar to you, it may be through his 1975 book The Relaxation Response, in which he advocated for a type of Transcendental Meditation®. He still thinks personal prayer can help healing, not because of divine intervention, but because prayer — like many forms of meditation — focuses the mind which helps decrease metabolism, heart rate, blood pressure, breathing rate and brain activity, all of which lower stress and promote healing.

###

Barry Evans gave the best years of his life to civil engineering, and what thanks did he get? In his dotage, he travels, kayaks, meditates and writes for the Journal and the Humboldt Historian. He sucks at 8 Ball. Buy his Field Notes anthologies at any local bookstore. Please.

CLICK TO MANAGE