Did you see the poignant story, a week or so ago, on a follow-up study of 14 (of 16 total) participants who lost enormous amounts of weight during the 2009 TV show “The Biggest Loser”? The winner, Danny Cahill, lost 239 pounds in seven months, going from 430 to 191 pounds. Despite what sounds like Herculean efforts in the years since — both severely limiting his calorie intake and following a daily exercise program – he’s put back nearly half of his lost pounds.

Danny’s not alone. All but one of the contestants either regained most of their lost weight, or are now heavier than before the program’s arduous regime. The reason, which surprised the researchers who followed this particular pack of losers, was that their resting metabolism slowed down after they’d lost weight and — this is the unexpected part — remained slow, six years later. (For another point of view, check trainer Jillian Michaels’ reaction here.)

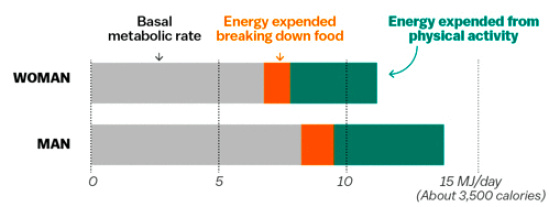

Your body’s resting metabolism is a measure of how many calories it burns at rest. When you have a normal metabolism – which is what all 16 participants had when they started the program — most of the calories you eat are burned off just keeping your body functioning (see the figure). After losing weight — especially after a crash diet-and-exercise program — the body’s metabolism normally slows right down. It’s still doing whatever it takes to function, but has somehow become more efficient, using fewer calories to do the same thing. The weird finding was that the metabolism of the losers remained low, one year, two years, six years after the show ended in 2009.

Components of total energy expenditure for average young person. Note that exercise only accounts for 10-30% of total calories burnt. (Vox)

Michael Schwartz, a doctor at the University of Washington and expert on weight control, told The New York Times: “…you can’t get away from a basic biological reality … As long as you are below your initial pre-diet weight, your body is going to try to get you back.”

Which is bad news for all the people, some 100 million Americans, who go on diets and/or exercise in order to lose excess weight: they’re fighting their own bodies. And it’s not just low metabolism they’re struggling with, but a raft of other mechanisms the body has up its sleeve to try to regain any pounds lost. For example, leptin levels usually plummet when you lose weight. Leptin is the main “hunger” hormone; lose weight, your leptin level falls and you’re hungry. Not just passing hunger, but chronic hunger, you’re hungry all the time, which leads, of course, to craving, binge eating and all the shame and misery that goes with that. In the long term, your body’s innate systems to recover lost weight, to get back to your “setpoint” weight, will nearly always trump your fervent resolutions to eat less. Will power, it turns out, is no match for biology.

President William Howard Taft had a chronic struggle with his weight, which sometimes exceeded 330 pounds. (Library of Congress, no photographer name.)

Even if you’re not overweight, in this era of easy access to cheap junk food it’s easy to put on just a pound or three every year — each of us eats about one million calories annually, and it only takes a slight imbalance. Seven thousand calories in one million doesn’t sound like very much, but that’ll add two pounds in a year. And as birthdays come and go, our metabolism gets increasingly efficient. In my own 73-year-old case, I never had to worry about my weight (to my wife’s chagrin). Now I have to eat less (especially sugar, which, thanks to insulin, turns readily into fat) if I’m not to see my setpoint climb a couple of pounds a year. Turns out I’m pretty average that way — some of us metabolize more, some less, efficiently than others. However, a pound or so a year is about the average increase as we age, everything else being equal.

Of course, a study of 14 participants does not make for a definitive scientific study, especially given the show’s fast and furious weight loss strategy, but it is noteworthy simply because these people were about as motivated as anyone can be to maintain that hard-won loss of pounds. Yet even they couldn’t do it, with one exception: a hard exercising, rigid-diet woman. (Most experts in the field recommend a slow-and-steady program to lose weight, giving your body plenty of time to readjust that damn setpoint.)

The good news from this study is what it says about will power and biology: you’re not a moral failure if you don’t stick to your diet! My wife Louisa Rogers, a weight-loss consultant in a former life, has long been an advocate of focusing on letting go of the shame associated with diets. “For most of the people I counseled, the shame involved in binging and being unable to control their cravings was a direct contributor — perhaps the main one — to their weight problems. Shame is gain! Release the shame, and you’ve got a fighting chance.”

CLICK TO MANAGE