Young residents of the Yurok Reservation gathered last week for a youth wellness workshop. | Photos by Ryan Burns.

Deep in the most remote reaches of the Yurok Reservation, half an hour past the nearest convenience store, near the dead end of State Route 169, a gravel driveway leads to the Morek Won Community Center. With a multi-angled roofline surrounded by pines and Douglas firs, the building holds a kitchen, boys’ and girls’ bathrooms and exactly half of a regulation-size basketball court.

On the Tuesday before Thanksgiving, roughly 20 kids from up and down the reservation gathered on the hardwood floor to talk about some tough topics, including historic trauma, domestic violence, substance abuse and mental illness. But their spirits were high under the fluorescent lights as they stood elbow-to-elbow in a large circle.

Annelia Hillman, the Yurok Tribe’s upriver peer youth liaison, described the rules for the ice-breaking game. The students were told to look at the floor until Hillman gave the command in the Yurok language, at which point they should lift their heads and look directly at one of their fellow students. If that student happened to be looking back then both students were eliminated and the game would continue, the circle getting smaller and smaller with each round.

Hillman, a young woman with the traditional facial markings once common among certain Pacific Rim tribes — a trio of chin stripes called a moko — had organized the day’s youth event shortly after returning from the ongoing protest against the Dakota Access pipeline. She stood among the students, giving the command. With each round a few students laughed and squealed as they looked up to find someone looking back at them. The circle shrank until there were just seven kids, and then three and finally one.

With their voices echoing against the high ceiling, the students made their way over to a group of chairs arranged near the wall for the next activity.

Ranging in age from sixth graders through high school seniors — and in height from barely four feet to almost six — the students had come from as far away as Klamath, which is only about 17 miles northwest as the crow flies but requires a circuitous two-hour, 67-mile drive — or a boat trip down the Klamath.

A road sign on the winding, one-lane State Route 169 warns drivers that the end is near.

More than half a century ago, Route 169 provided a fairly direct route upriver, but the stretch between Klamath Glen and Wauteck Village has remained impassable since being wiped out in the floods of 1964. As a result, the upriver communities such as Weitchpec, Martins Ferry and Pecwan have remained remote and profoundly isolated from the outside world. Many residents have no internet or cell service, and quite a few lack electricity.

As in many other indigenous communities, poverty and substance abuse have taken a toll on the Yurok Reservation. With scarce job opportunities, the younger generation often struggles to find hope. In December 2015 the Yurok tribal council declared a state of emergency following seven suicides in an 18-month period. Most of the tribe members who’d taken their own lives were teenagers; the oldest was just 32. And they all lived near the tiny community of Weitchpec.

Since the emergency declaration the tribe has taken many measures to address the underlying issues. By collaborating with federal, state, local and tribal agencies, Yurok leadership has expanded social services including mental health training, alcohol and drug counseling, parenting classes, suicide-prevention courses and more.

Last week’s youth wellness event was part of the ongoing effort to identify and address the factors that contribute to chronic depression and suicide.

“I’d just like to say that today we’ll be diving into some heavy conversation, and it might get personal,” Hillman told the group. She asked everyone to respect differing opinions and vow to maintain confidentiality. “We want to be able to openly share and be comfortable in this circle,” she explained.

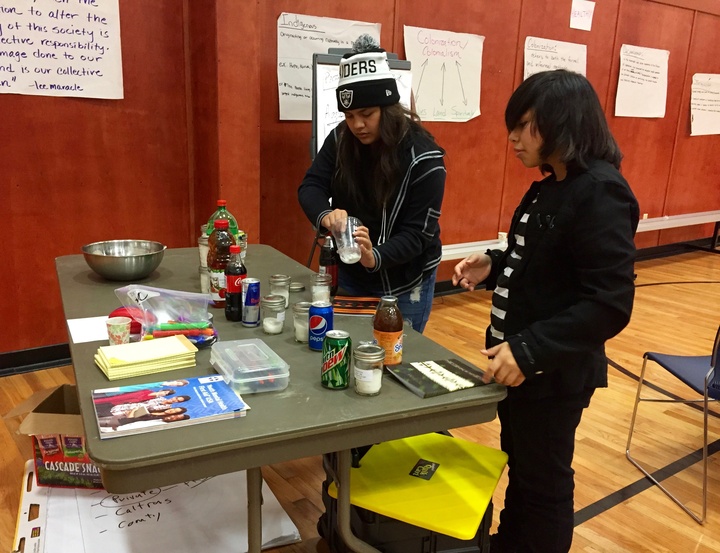

Two volunteers scoop sugar into jars to see how much is included in popular beverages.

Another tribe leader then led the kids through an activity demonstrating techniques for positive and assertive communication, as well as active listening. A health and wellness coordinator showed them how to read nutrition labels for sugar and had volunteers dump heaping spoonfuls into jars to visualize how much sugar is in a Dr. Pepper, a Red Bull and a bottle of apple juice.

“Sugar is a poison,” Hillman told the group. “It was one of the first things introduced to native people, especially in California – sugar, coffee, things that were never part of our diets before. It has begun to change our body, our health, our DNA structures.”

She backed toward one of several hand-written signs on butcher paper taped to the wall. “That’s a good introduction into talking about colonization,” she said. “How many of you know what that is?”

A young boy volunteered to read the dictionary definition on the wall, after which Hillman elaborated. “It’s how we have been taken over by force,” she said. “They forced institutional beliefs, ideological beliefs, economic and behavioral ideas. … It changed our whole way of life. It changed our diets. It has changed our physical structures, the way we think about things, how we value things — money was a new concept.”

She asked the kids for examples of harmful influences in the community.

“Pollution,” said a soft-spoken teenage girl. Others chimed in: “Crime.” “Heroin addicts.” “Violence?” A small boy swinging his legs piped up, “Donald Trump!” and Hillman giggled. “Right!” she said with a smile. “He is the epitome of all of our problems.”

Many of the tribe’s problems, from substance abuse to depression and anger, can be traced to colonization and oppression, Hillman said, and the community should strive to liberate itself as much as possible. “We wanted to make this the foundation of what we’re here to work on today. Our families, our land and our spirituality – these are the things we want to strengthen again.”

The next activity was aimed at strengthening social bonds. It was called “human bingo.” Each student was given a bingo card with a five-by-five grid. Inside each square was a statement about life experience. “Comes from a blended family.” “Likes to swim.” “Has been to a Jump Dance.” “Has a safe person to talk to.” They were told to wander among each other, having fellow students write their name in a square that applied to him or her. Afterward they again gathered in a big circle to assess the results.

“Who here has caught a sturgeon before?” Hillman asked, and about a third of the kids stepped forward to indicate they had.

“Who here has a safe person to talk to?” All but a few stepped forward.

Most of the questions were innocuous: Who likes to swim? Who loves their pets? But more serious ones were mixed in.

“Who has seen a behavioral counselor?” Roughly half stepped forward.

“Who has had their life affected by drugs or alcohol?” All but one.

“Who has suffered from depression or anxiety?” About three-quarters of the kids stepped forward. One, a precocious young boy, volunteered, “It sucks.”

“Yeah, it does,” Hillman affirmed. “It’s an ongoing struggle sometimes.”

Despite the depression, substance abuse and poverty that afflicts the Yurok Tribe, many young people do excel academically and professionally. Teresina Obie is one of them. After growing up in Klamath she graduated from college and went on to obtain her master’s of social work degree from Fordham University in New York City. Now she’s back on the reservation, employed by the tribe as its Indian Child Welfare Act social worker.

Obie was on hand at last week’s workshop and said most families on the reservation want to address the social ills afflicting the community, but logistics make it difficult to arrange this type of event.

“Really the hardest part is transportation — getting to and from and providing food,” Obie said. The Yurok Reservation covers more than 63,000 acres, hugging the banks of the Klamath River from the mouth to 44 miles upriver and extending a mile on either side. From the upriver communities it takes more than two hours by car to reach Tribal Headquarters in Klamath; that’s assuming access to a car, which many residents lack.

“A lot of families that I’ve talked to, they’re so impacted by poverty,” Obie said. “But they do realize that there is a problem. They want to help their kids, so they’ll send their kids off. A lot of the kids today are affected by drugs and alcohol in the home.”

Events like this workshop help them realize they’re not alone and can talk about such issues without being judged, Obie said.

Trish Carlson, the community liaison with Yurok Social Services, also attended the workshop, offering a presentation on historical trauma. She cited scholar Eduardo Duran and his theory that intergenerational trauma tends to impact the younger generation, so that kids wind up bearing the burden.

“Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for natives age 10 to 34,” she told the group. “With other ethnicities it happens [more frequently] in mid-life or older, but with us it’s younger.”

It’s too soon to tell whether the tribe’s response to the suicide crisis will improve those statistics, but the early signs are promising. According to the tribe there have been no youth suicides thus far in 2016.

“There’s always been a lack of services in this area, so it’s important to keep the momentum going on the subject and educate the community,” Carlson said.

Late in the afternoon the skies opened up and pummeled the roof of the small community center. Carlson stood in front of the kids and asked if they knew what the word “resiliency” means.

“When something’s hard, it’s what helps you to keep going or stay strong,” she said. “What do you think has kept native people strong?”

“Praying?” one girl suggested.

“Family,” said another.

“Culture,” said a teen boy.

Hillman approved of each kid’s answer and then offered one of her own. “And being willing to talk about heavy topics – colonization, grief, historical trauma – that is amazing and incredible to see. It’s really heartwarming to see that.”

Approximate location of the Morek Won Community Center.

CLICK TO MANAGE