Morning mist in Galicia, nearing journey’s end.

We’re currently following regular posts from two friends as they walk the Camino de Santiago in Spain. In case you’re neither (1) Catholic, (2) a long distance walker or (3) a fan of that awful Martin Sheen movie “The Way”: the Camino is a 1200-year-old pilgrimage route that ends at Santiago de Compostela, in Galicia, northwest Spain. Having walked it ourselves (from the French border town of St. Jean Pied de Port to Finisterre), we are vicariously appreciating their ups and downs — literally and metaphorically —as they follow the same route we walked in 2001, the same one peregrinos (pilgrims) have been walking since around 900 AD.

According to author Robert Sibley, “In the Middle Ages, the act of pilgrimage was regarded as an effort to recover the original condition of mankind, the innocence enjoyed before the Fall from Grace. For medieval men and women, going on a pilgrimage, whether to Rome or Jerusalem or Santiago, was often the most important act of their lives.”

Metal sculptures along “The Way” recalling pilgrims from the Middle Ages.

So when Louisa and I walked our camino, we approached it with the same reverence we’d have for a meditation retreat — or in this case, a long meditative walk. And indeed, after the first two or three days of resistance (“We’re walking how far???”) I fell into my rhythm. For hours on end, all I was aware of was my footstep, the next rock on the road, the clump of grass by my side.

800-year-old bridge leading into Hospital del Orbigo.

I had imagined my mood would swing up and down more than it did. After a few days, my mental ‘stuff’ became a side show — same old, same old — as my brain turned to mush. The Camino itself, just walking, following las flechas amarillas, the yellow arrows: that was the real stuff. And I’d thought, before we started, that I’d be writing my heart out every night, recording my amazing insights and revelations. Actually, I filled exactly three journal pages the entire time.

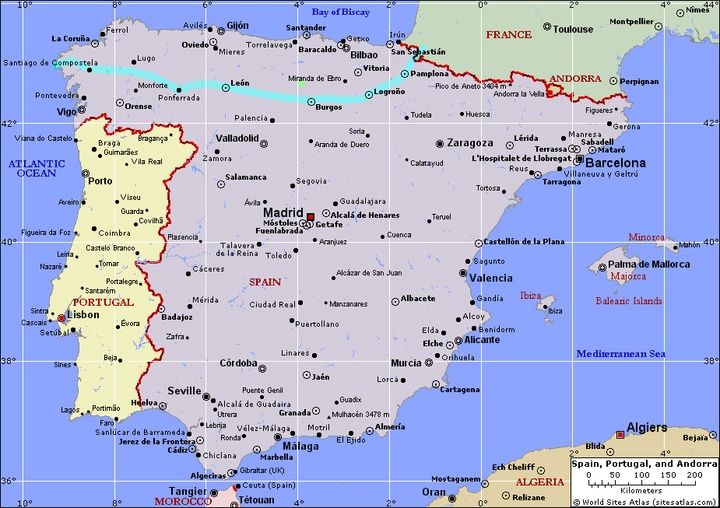

The route of the “Camino Francés” (light blue) runs from the Pyrenees west to Santiago de Compestela and beyond to the Atlantic at Finisterre.

Our route was the ‘standard’ one, the Camino Francés, starting in France, ending (27 days later) at the cathedral of Santiago de Compostela. Where Louisa (whose 50th birthday we were celebrating) advised me that real pilgrims continued on to the coast at Finisterre, another three days walk. 540 miles in all, over a million steps. (In the old days, of course, they had to walk back home, too!)

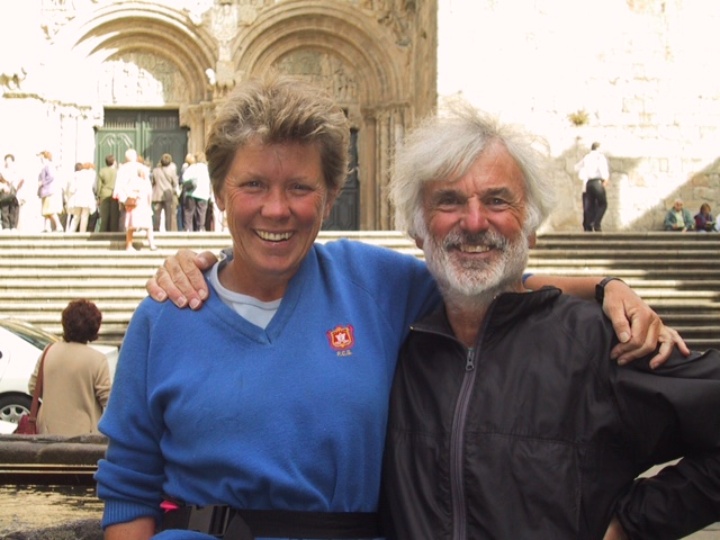

Arriving at the cathedral in Santiago, only to be informed by my beloved that we were now walking on to the coast.

Our adventure was at times physically demanding. Not so much any one day’s 15-20 miles, but the day-after day pounding on our feet and knees. In common with most of our fellow peregrinos, we had chronic blister problems, and at once stage I had to take an antibiotic for an infected toe. Sus ampillos son sus pecadillos (your blisters are your sins) we were told, in all seriousness.

We’d start in the dark about 6:30 a.m. and stop around mid-afternoon. With a couple of exceptions, we stayed in refugios, pilgrim hostels — very basic dorms — with showers (hot if we were lucky and/or early) and kitchens, although Louisa and I mostly ate our “pilgrim meals” in nearby bars. For about $5 each, our comidas peregrinas weren’t too inspiring, but anything tastes great when you’re tired and hungry, and the meal always included a generous flagon of local red wine. (One time we’d just finished our supper in a bar when a fellow peregrino walked in and asked about the food. I told him I thought it was just wonderful, one of the best meals I’d ever had. Later, as we walked back to the schoolhouse where we spent the night, Louisa said, “I’ve never heard anyone so enthusiastic about eggs and chips!” I still say it was a great meal.)

Long hot days on the meseta.

The terrain changed dramatically every few days: we started off in the Pyrenees (first day over a pass from France to Spain) followed by several days in the foothills, then the meseta, Spain’s great central plain: flat, treeless, brown and dry, where the trail was dead straight. Finally the province of Galicia: green and wet, up and down, tight rocky paths between ancient stone walls. Day after day, rain or shine, all we had to do was follow the yellow arrows. So easy. I miss them.

Narrow lanes in Galicia.

Our standards changed on the Camino. The day we left the meseta and entered Galica, we spent the afternoon hauling our bodies up a steep track to the foggy village of El Cebreiro. When we finally arrived at the refugio, we were assigned to a mixed dorm with dozens of beds. Post-shower (warm!), I was lying in my sleeping bag, cozy and dry after our long day. Normally I hate dorms. I love my privacy. But in this room full of young Spanish guys making penis jokes, a couple making out on the next bed, smelly socks and damp clothes all over the place, my only thought was, “I couldn’t be happier!”

Typicial refugio with clothes drying outside.

CLICK TO MANAGE