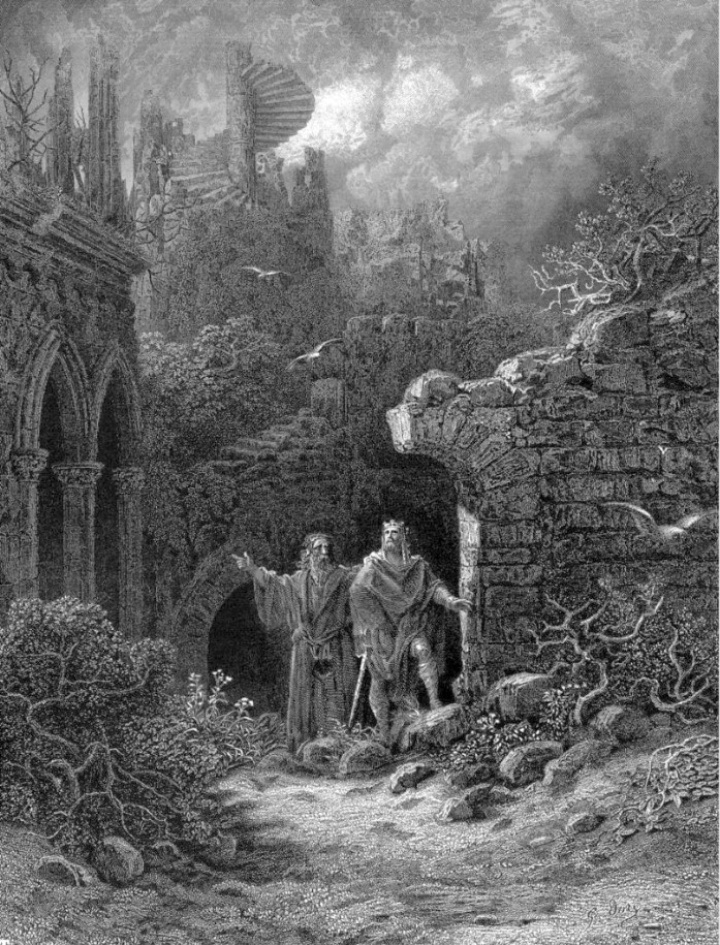

Merlin recalling the Golden Age for Arthur, from Idylls of the King by Tennyson (Gustave Doré, 1868)

I’m getting ready to teach my class on King Arthur again (11/17). I’ve been giving this class every four or five years for decades, previously at community colleges and now through OLLI (HSU’s extension program for 50+). And, per usual, I can understand why students go into ancient history and archeology—and for that matter, quantum physics, mathematics, esoteric stuff—that is, some subject far removed from the ever-more-frantic headlines of the present time. They do it to escape, the same reason perfectly nice folks become monks and nuns living far from all this mess, and why my pal Bob became a hermit, taking himself way, way up the coast of British Columbia: to get away from it all, to off-load the weight of our current craziness.

Not that Arthur is exactly history, of course. The Arthur we read about and watch movies about is a myth created in the Middle Ages (in Oxford and later in France) during a time of anarchy, wars and the Black Death, a time when maybe one in five births led to the mother’s death, while childhood diseases carried off a quarter of children before their fifth birthday. Arthur was an antidote to all that, the hero everyone craved, harkening back to a golden age of valor and Star Wars-like good guys and bad guys. In the earliest versions, Arthur rallied the British defenders against invaders from the continent. In one day, he slew 960 of the enemy …and no one struck them down except Arthur himself, and in all the wars he emerged as victor. He was the shining light in the middle of the Dark Ages, the Che Guevara of his time, a man for the moment.

Avalon? Glastonbury Tor, Somerset. (Barry Evans)

Which moment? The one following three centuries of rule and order, the Pax Romana (peace imposed by the Roman Empire), when educated people spoke Latin, literacy blossomed, good roads connected thriving cities,, trade thrived and actual money replaced a barter economy. All that came to an abrupt end when the Roman legions decamped to continental Europe in 410 AD and Germanic tribes (Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Frisians) first raided, then settled in what would be called England (Angle-land). It was a time when, according to a contemporaneous account, “the red tongue of flame licked the whole land from end to end.”

However, several lines of evidence point to a setback for the invaders, roughly for the hundred years between 500 and 600 AD. Instead of continuing their advance across the country, the continental tribes remained within the home counties (around London) and the eastern seaboard. Seems that something or someone stopped their westward incursion, following a legendary “Battle of Badon” (around 500 AD), a noteworthy victory for the defending Britons, i.e. Celts. Hence the need to invoke a British (or maybe a Romano-British) hero to account for the century-long pause. At which point, Arthur is your man to stand up to the invaders. Was there a real Arthur? That would be a definite “maybe.” All we have is later and much-debated evidence for such a dux bellorum or war lord, a misty figure behind all the tall tales.

Arthur’s birthplace (honest!): Tintagel, Cornwall. (Barry Evans)

In the Middle Ages, starting maybe 600 years after Arthur’s time, those tall tales were the stuff of epic stories and poems told by bards and sung by minstrels around the fire. Three sets of tales, or “matters,” dominated the epics of that time: the “Matter of Rome,” which included Homer’s legends of Troy and the subsequent founding of Rome by Aeneas, woven in with stories of such historical giants as Alexander and Caesar; the “Matter of France,” which romanticized The Frankish emperor Charlemagne and his 12 knightly “paladins,” including the valiant—and doomed—Roland, whose story is told in the Chanson de Roland.

Camelot, from Tennyson’s Idylls of the King (Gustave Doré, 1870)

And the “Matter of Britain”: that was all about Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Those who listened, spellbound, to the thrilling stories of derring-do, honor and treachery, battles won and battles lost—they would have known the plots inside out, known how it all turned out—like watching Rocky Horror over and over again, speaking the lines along with the bard, a shared communion, an antidote to the daily grind.

We could do a lot worse than escape from our own daily round of news-weirdness and lose ourselves in the magic of Arthur and his heros and his betrayers. They’ll still be around when all the petty politics of our time has been lost to memory.

“‘I am half sick of shadows,’ said the Lady of Shalott” (Elaine the Lily Maid) (William Waterhouse, 1888)

CLICK TO MANAGE