Eclipse of July 11, 1991 from Baja California. (All photos by author).

I’ve been reading, here and in the Journal, how Humboldt will be getting a “pretty good” partial eclipse assuming clear skies tomorrow, August 21. The implication is that when 87% of the sun’s disk is covered by the moon (as will be the case in Humboldt), folks will be getting 87% of the full experience.

Sorry, you won’t. The view from Humboldt will be at best a watered-down, insipid, ho-hum version of the real deal. Sparing you a more graphic analogy, think of watching Love Story on your own versus a night spent next to someone you think you might want to spend the rest of your life with. A partial solar eclipse is nice, mildly interesting. A total one can be life-changing.

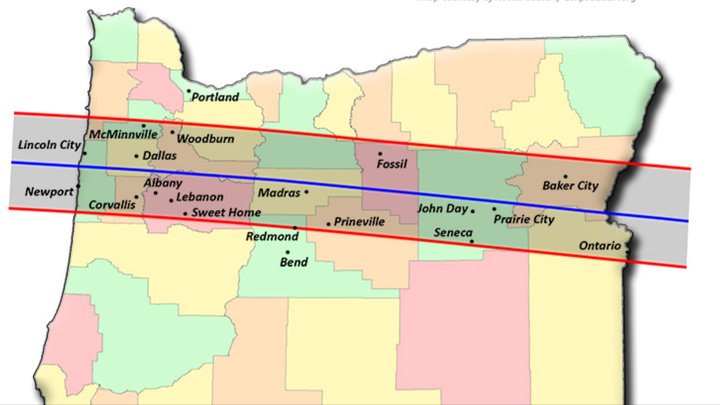

Path of totality, Oregon.

If I were on the West Coast right now, I’d now be heading for Grant County, eastern Oregon. (I’m not—I’m on the other side of the Atlantic.) But if there’s any way you can get yourself in the path of totality, do! There might be one or two other people there, so go early…

Here’s what I wrote soon after the 1991 total eclipse, while it was still fresh in my mind and heart:

In the Moon’s Shadow

I thought I knew about total eclipses of the sun.

After all, I’d been reading about them for decades, I’d looked at hundreds of photographs of eclipses and discussed them at length in my popular astronomy classes. I had once written, after attending a slide show by veteran eclipse-chaser Jacques Guertin, who’d witnessed the March 1988 total solar eclipse from Borneo.

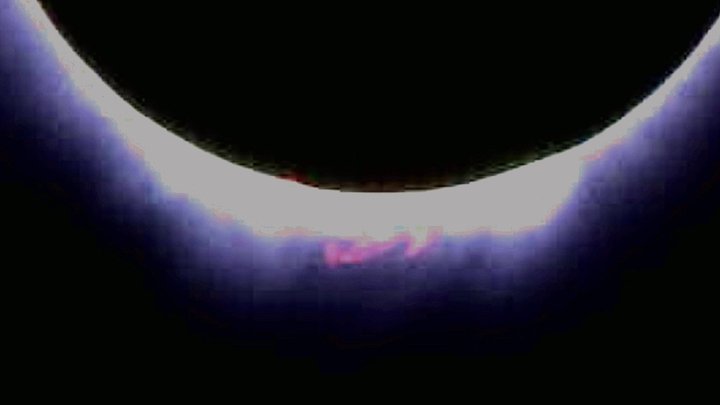

“We watched a series of slides as the moon moved across the face of the sun, until only the so-called ‘diamond rings’ were left. These are the final glimpses of the sun’s disk seen through valleys on the moon’s limb, before the sun disappears completely. At the moment of disappearance, the sun’s corona, or outer atmosphere, becomes visible in its glory, a soft aura of light around the moon. Then too, for those few seconds of totality, prominences of hydrogen gas can be seen if they’re present. And for the eclipse of March 1988, they were indeed present, arching above the sun’s surface to a height corresponding to ten Earth diameters! The photographers captured these unusually fine displays.”

Doesn’t that sound as if I’d know what to expect when viewing my first “live” one, from Baja California on July 11, 1991? The fact is, I didn’t have a clue. Those six-minutes-fifty-two-seconds of totality caught me utterly unprepared. My life is now divided into BE and AE (Before Eclipse and After Eclipse). It was all shockingly beautiful, in particular the ruby-red prominences and the vast size of the corona.

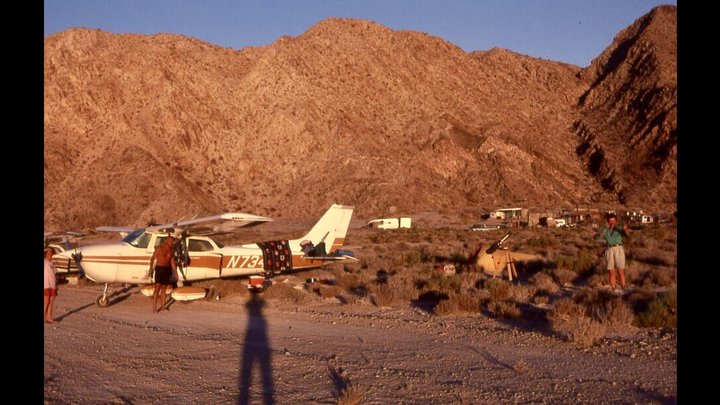

How we got there.

Getting there, they say, is half the fun. It certainly was an experience. Four of us—my wife Louisa, our pilot (who had answered my ad posted at the local flying club) and his friend, newly arrived from Germany—squeezed into a Cessna 172 in Palo Alto, California five days before the eclipse. Three days and many adventures later, we landed at Los Friales, Baja. Why Los Friales, not universally known as a center of world culture? Because it had the closest airstrip to the eclipse centerline on Baja’s eastern coast.

Our observatory with 4-inch refractor telescope.

By the morning of July 11, we were well organized. My four-inch refractor telescope was ready in the “observatory” (a patch of sand protected from the wind by a tarpaulin) and right on time I saw first contact, the moment when the moon’s disk began its traverse across the face of the sun. An hour later, with two-thirds of the sun’s disk covered, the temperature had dropped noticeably and the light was slightly dimmer. Cacti took on a pastel color.

Minutes later, other subtle changes occurred. We saw and heard birds, usually quiet at noon in that arid climate, as they began to wake up in this pseudo-sunset. Shadows became sharp, so that I saw individual hairs on my head silhouetted on the sand at my feet. Hundreds of little crescents could be seen beneath a straw hat, whose holes focused the sun, the way a pin-hole camera works. Then, right on time, the mountains to the west suddenly darkened as the moon’s shadow, racing at 1,300 mph across our planet, cut off sunlight from the peaks. Seconds later, as if someone had turned a switch, it happened: we were in totality.

It was far from pitch-darkness (admonitions to have flashlights handy proved unnecessary), but the abruptness of the transition from the sun being just visible to totality was a shock to us all, no matter how well prepared we were. Overhead, the white wreath of the corona, much larger than we’d expected, extended two or three sun diameters from what appeared to be a round black hole in the sky. With the naked eye, we could just make out prominences of hot gas. Through the telescope, they were awesome: two bright ruby-red arches opposite each other, one reaching up to a height of at least ten Earth-diameters from the solar “surface.”

The minutes whizzed by, and then, far too soon, came the moment of the sun’s return. I was looking through my telescope when first a single bead of sunlight, then an avalanche of photons, an incandescent blast, hit my retina: it was overtime to replace the Mylar solar screen. We’d read previously that people generally cheered when the sun returned. Not our little party. We looked at each other with the expressions of those who had seen a miracle, and weren’t ready for it to be over. Then, inevitably, came the first words following totality:

“When’s the next one?”

CLICK TO MANAGE