The title of the paper isn’t exactly a turn-on, neither is the name of the publication in which it appeared two years ago. “Nature experience reduces rumination and subgenual prefrontal cortex activation” appeared in May, 2015 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. I think it’s super-important, whatever it’s called and wherever it was published, worth a few minutes of your time, I hope. (A commentary on the paper appeared last weekend in the NYT’s “Well” section.)

So the deal is that a Stanford researcher enlisted a group of volunteers and assigned them randomly into one of two groups. The first cohort wandered for 90 minutes through the back of the Stanford campus, where there are woods — what he terms a “natural environment.” The second group was assigned 90 minutes walking along a busy urban highway — El Camino or Page Mill, I assume. Both groups walked alone, undistracted by phones, music, etc.

Their mental state on their return was judged in two ways. One, they self-reported (via a questionnaire) their level of rumination during the walk, rumination being defined as “a maladaptive pattern of self-referential thought that is associated with heightened risk for depression and other mental illness.” Two, neural activity in their subgenual prefrontal cortex was measured. This activity has previously been associated with a self-focused behavioral withdrawal linked to rumination. In a nutshell, the level of rumination (both self-reported and neural activity) was unchanged for the urban walkers, but reduced in the nature walkers. Bottom line: “These results suggest that accessible natural areas may be vital for mental health in our rapidly urbanizing world.”

Daby Island egrets (Barry Evans)

So, taking this at face value — it all seems kind of obvious, doesn’t it? — let’s get local. Living (usually) in Old Town, I find that it’s pretty hard to find nature, or even a fair facsimile of it. There’s the boardwalk, of course, but that’s more depressing than uplifting these days, for reasons we needn’t get into here. There’s the waterfront trail along Halvorsen Park, but it’s kind of sterile — it could really use trees. Many trees. My own way of getting into nature is to paddle my kayak out into the bay, between Woodley and Indian islands or down the back of Indian and commune with harbor seals, egrets and blue herons, but not everyone has a kayak or the time to indulge in such relaxation.

Indian Island rookery (Barry Evans).

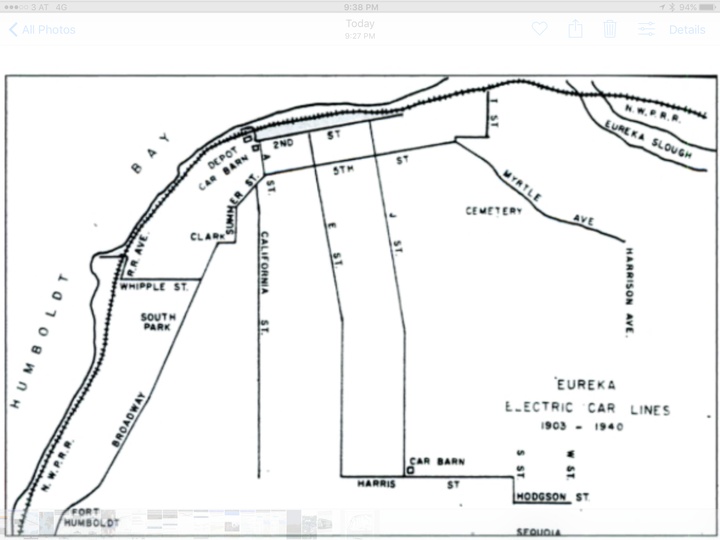

Really, the closest we have to “nature” is Sequoia Park — an hour’s walk or 20-minute bike ride from Old Town, maybe 10 minutes by car. Which could explain an oddity of Eurekan history, that is, why did the old-timers build an electric streetcar line all the way to Sequoia Park from Old Town? It’s not like the park was a thriving population center back when the tramcars were in operation. Yet from 1903 to 1940, not one but two lines, down E and J Streets, ran from 2nd Street south of Harris, thence reaching almost to the park at Hodgson and W.

Electric streetcar lines 1903-1940. (Humboldt County Historical Society)

I like to think the streetcar planners back then intuitively knew what the Stanford study quantified, that being in nature is good for mental health. Not to mention physical and, er, spiritual health. Having eliminated nature in the main part of Eureka (by cutting down all the trees) Sequoia Park was where folks could go to recharge their batteries and drop their worldly worries. And, unlike driving or cycling there today, they could get there stress-free on the streetcars.

And let their ruminations take care of themselves.

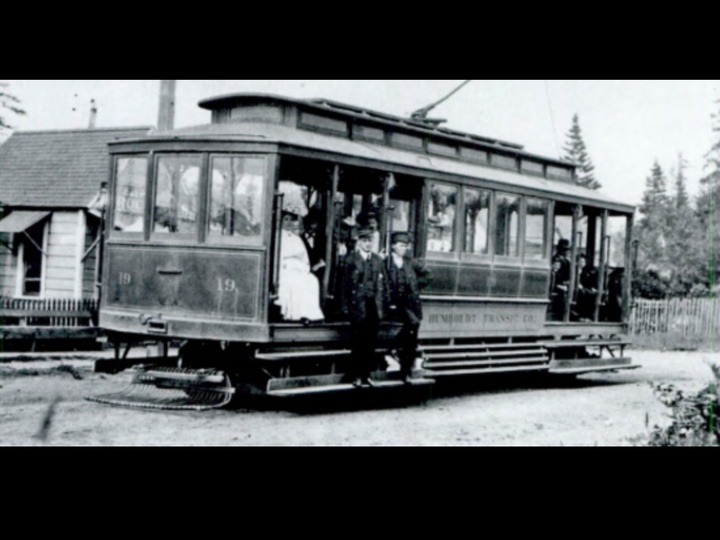

End of the line, corner of W and Harris Streets, 1906. (Original at Clarke Historical Museum)

CLICK TO MANAGE