Napoleon Bonaparte is a controversial figure in French history, perceived in the same way many Americans view Robert E. Lee — “brilliant but flawed.” We recently spent two weeks in Napoleon’s shadow in the south of France, based in the Provencal town of Sisteron on the lovely Durance River.

Sisteron, France (Barry Evans).

Sisteron is located between Marseilles and Paris on “Le Route Napoleon,” the route taken by Napoleon and his motley band of renegades following his escape from the island of Elba in March 1815. He was a free man for 11 months, including the 100 days as self-proclaimed Emperor of France that culminated in the Battle of Waterloo. After his defeat, the victorious allies exiled him on the island of St. Helena in the south Atlantic, where he died five years later.

Portrait of Napoleon following his abdication in 1814, prior to exile on the island of Elba. (Paul Delaroche, public domain)

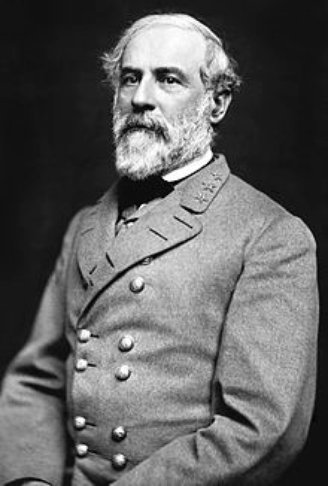

Robert E. Lee in March 1864 (Julian Vannerson, public domain)

Napoleon,

for the most part, was a liberal dictator. He saved his country from

the worst excesses of the French Revolution and put France back on

the world map. After he fought numerous successful campaigns and

battles, France completely dominated Europe. A single battle,

Austerlitz, fought on Dec. 2, 1805, changed the map of Europe and

ended the 1,000-year-old Holy Roman Empire. When he wasn’t leading

his troops, Napoleon elevated science and learning, and instituted

laws (the Code Napoleon) still in use today, including in

Louisiana.

Over on this side of the Atlantic, Lee’s Austerlitz was the week-long battle of Chancellorsville, fought between the Union Army of the Potomac and the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia in early May, 1863. Despite being outmanned two to one, Lee outmaneuvered Union general Joseph Hooker and won a decisive victory. Like Napoleon, Lee had a knack for out-thinking his enemy, for rapid deployment, and for inspiring loyalty in his troops.

Napoleon and Lee also share less admirable qualities — seen from the viewpoint of generations later — in their attitude to black slaves. For them it was simple: Blacks were inferior to whites. For his part, Napoleon reinstituted slavery in French colonies and put down a slave revolt in Haiti, the results of which are still felt in that desperately poor and badly run country.

Lee, on the other hand, was a Virginian plantation owner and therefore a slave owner. In a 1856 letter to his wife he wrote, “The blacks are immeasurably better off here than in Africa, morally, socially & physically. The painful discipline they are undergoing, is necessary for their instruction as a race, & I hope will prepare & lead them to better things. How long their subjugation may be necessary is known & ordered by a wise Merciful Providence.” Perhaps his most repugnant actions in regard to his treatment of slaves was to split up African families on his plantation, as documented by historian Adam Serwer in a recent issue of The Atlantic, “The Myth of the Kindly General Lee.”

Yet

somehow the myth of Lee, like that of Napoleon, exonerates the worst

and exaggerates the best, as any good eulogist at a funeral knows how

to do. Meaning, unfortunately, that our rose-colored view of history

has limited application in its ability to teach us anything.

Parade near Sisteron last summer celebrating Napoleon’s march through the area in 1815. (Barry Evans)

CLICK TO MANAGE