“May you live in interesting times,” goes the Chinese blessing, which seems particularly appropriate this past week. I certainly have much to say about politics and democracy, but need to let it all ferment brainwise before putting pen to paper, so to speak. Instead, to maintain a semblance of sanity, I want to offer my paean to a technology dating from 1863: the urban transit system known by many names, including “underground railway,” “metro,” “subway,” “tube,” “U-bahn,” “heavy rail,” or simply “the underground.” Today, some 160 such systems carry commuters economically and rapidly beneath the world’s busiest cities.

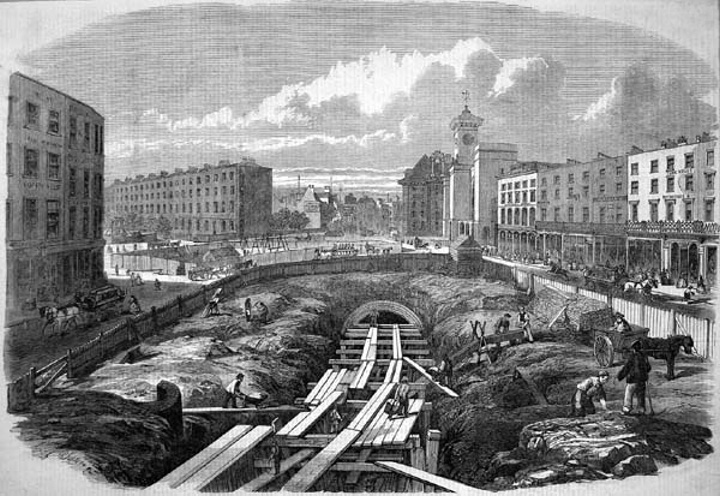

Building London’s Metropolitan Railway, 1861 (Percy William Justyne, public domain)

Actually,

the underground often isn’t. Take London. Less than half of the

city’s underground, or tube, is below ground, but the name sticks

because it’s almost always underground in the densest parts of the

city, where real estate is at a premium. That was as true in 19th

century London as it is today — the pioneering Metropolitan Railway,

dating to 1863 (the world’s first) was located below “New Road”

between Paddington and King’s Cross main-line railway stations,

using cut-and-cover engineering techniques. And that’s the beauty

of such systems, where the trains have an exclusive right of way,

unlike buses and taxis, for instance.

And they’re so efficient! A typical subway car has a capacity of 100-150 passengers, and with computer controlled trains (many now are fully automatic and driverless) and at slower speeds than interurban trains, rush hour “headway” (the time interval between trains) can be as short as 90 seconds. At 1,000-1,200 people per train, over 30,000 passengers can be transported every hour. (According to Wikipedia, Hong Kong’s MTR subway can move 80,000 people per hour.) That adds up to a lot of trips: over three billion rides per year on the Beijing subway, the world’s busiest.

Not only are subways efficient in terms of ridership, but they run on electricity — usually direct current from a “third rail.” True, electricity generation isn’t pollution-free (although modern “scrubbers” on coal-fired power plants help minimize the release of carbon dioxide and acidic gases into the atmosphere) but, unlike most surface vehicles, subway trains don’t emit noxious gases directly into city air. (The Metropolitan Railway originally used coal steam locomotives — cough, cough. Electricity took over in 1907.)

Kiyevskaya metro station, Moscow (Antares 610, Creative Commons)

Subway stations are opportunities for public art. I was entranced years ago traveling on the busy Moscow Metro by the ornate, often art-deco, station architecture. And recently, three Upper East Side stations on New York’s new Second Avenue subway drew crowds wanting to view new public art commissioned by the MTA Arts & Design program.

Mexico City Metro (GAED, Creative Commons)

Last week, I was once again appreciating Mexico City’s metro. It’s a world class operation, serving 1.6 billion passengers a year on its 195 station system. Ten of its twelve lines run on rubber tires, one reason why it escaped damage during the otherwise-devastating (magnitude 8) earthquake of September 19, 1985. Unlike, for instance, New York’s awkward payment system, Mexico City’s metro allows free transfers between lines — you can travel anywhere for just five pesos, $0.23. (And that includes, should you be so inclined, an education on the cosmos and evolution as you walk the long corridor between lines 3 and 5 at La Raza station.)

London underground today, based on Harry Beck’s original design.

One last homage, this one to Harry Beck, an artist whose 1931 map of the London underground has inspired virtually all subway maps since. Beck’s design had the lines running in straight lines with stations located at equal distances (a far cry from geographical reality). The 150th anniversary of the first underground was fittingly celebrated by a Google Doodle on January 8, 2013. Thanks Harry — you made the lives of city dwellers the world over that much simpler.

Google Doodle, 1/8/13

CLICK TO MANAGE