Over

the last couple of years, I’ve been learning to play, and composing

music for, a collection of idiosyncratic musical instruments that I

built from found objects and recycled materials. I find tinkering

with these little gadgets very relaxing, and doing it encourages me

to think about music in new ways. I’m not sure that playing these

new homemade instruments makes me a better musician, but listening

to them has made me a better listener.

These days, we find ourselves swimming though a soup of slickly produced high-tech earworms designed to reach out and grab the listener right from the first note. The music business is highly competitive and musicians work very hard to grab an audience and hold their attention. This tends to make listeners lazy, and does for listener’s tastes what junk food does for a kid’s palette.

As

in most of life, what works for business does not necessarily serve

the needs of the people. Music is a form of communication. We call

media “media” because it mediates our communications. Instead

of hearing each others’ music, mostly we hear expensive, sterilized

pap, made by professionals, for corporations. The internet has

reduced music to a commodity sorted by genre, or tailored to your

tastes by their special proprietary algorithm. Just what you need — a

whole bag of cheese doodles for your ears.

Music has an important role in culture, but for music to effectively communicate new cultural ideas, people have to listen, and listeners need to hear something outside of their comfort zone once in a while. Active listeners, constantly search for new, different and adventurous music to listen to, while passive listeners happily endure a familiar genre of music all day, and measure it’s quality largely by how well produced, and reproduced, it is. We need more active listeners. Active listeners are more inclined to seek out the music of their peers, rather than the corporate media products designed to fill the space, but empty the music of context.

Listening to any music, well played or not, derivative or original, reminds us of the miraculous acuity of human hearing, and the overwhelming power of silence. Listening to challenging music affects the mind in the same way that entertaining challenging ideas does. Listening to challenging music is good exercise. It stretches the imagination, focuses the mind, and allows for a kind of communication that conveys ideas and emotions though rhythm, timbre, pitch and melody. Active listening is always rewarding, whether you’re re-enjoying familiar music, exploring new music, or just listening to the sounds of your surroundings.

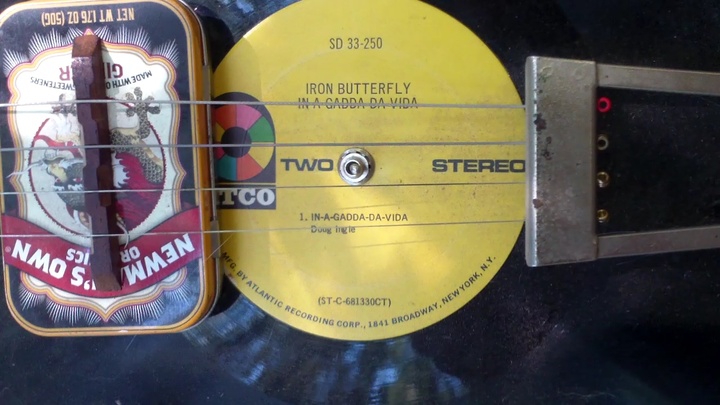

I’ve assembled a collection of instruments you’ve never heard before. They’re not much to look at, and they sure don’t sound like a Stradivarius, but they do, in a way, represent, and celebrate, the abundance of our time. Now that the planet has been laid to ruin, we inherit a wealth of waste. Never before, at any time in history could an average person find, free for the taking, so many exotic materials, from high-tech polymers and plastics, to high-carbon steel, aluminum, brass, lead and half a dozen other metal alloys. We find these exotic materials in the most bizarre shapes and forms, all around us. We call it “garbage.”

At the same time, traditional instrument-making materials like rosewood, ebony and ivory, have all become rare, endangered and threatened with extinction. As these materials disappear, the music those instruments spawned rings hollow. How sad will it be to hear a piano in a world without elephants? The repertoire of traditional instruments is as exhausted as the natural resources necessary to create them. We’ve heard it all before.

New high-tech computer-based instruments don’t do a lot for me either. The more software you interact with, the more those software programmers become collaborators on your music. These programs always suggest ways of working, if not sounds to use, and it’s no accident that a lot of artists who use these programs tend to sound similar. These programmers collaborate with you, but they don’t collaborate individually. They make the same suggestions to a whole generation of young artist. Far from freeing musicians from their own musical limitations, music software allows corporations to mediate and monetize the composition of music, in addition to the production, promotion and distribution of it.

So, from the ruins of the industrial revolution, in an unmediated act of creativity, I’ve assembled an ensemble of unique musical instruments, and composed some music for them that I hope reflects my time and place in history. I call it “post-industrial chamber music.” I hope you’ll take the time to listen to it. You can hear the entire album, or download it for free at this link.

###

John Hardin writes at Like You’ve Got Something Better to Do.

CLICK TO MANAGE