“I have promised

myself suicide the way other people promise themselves a new car,

gleaming and spiffy … I understand that taking one’s own life is

not in itself a positive thing, of course, that it represents a

turning on the self of the most radical order, but I also think it is

possible to look at it as a kindness, a way of paying utmost

attention to one’s own utter bereftness.”

— Daphne Merkin, from This Close to Happy: A Reckoning with Depression

###

For any of us who have had a friend or a relative commit suicide — and I suppose that’s all of us — the word “kindness” probably wouldn’t have come to mind when we heard the news. “Tragedy,” more like it, as we try to put ourselves into the victim’s place. (“Victim?” Does someone about to take their own life think of themself as a victim? A victim of life, perhaps — but that’s why they’re doing what they’re doing, the very opposite of victimhood. They’re taking control.)

I included the lengthy quote above from a new book by essayist and novelist Merkin, excerpted in January’s Harper’s, because the author makes it clear that, in her view, there’s nothing tragic about suicide. (Well worth reading, if only for her crisp prose, it’s at the library, starting on page 17.) I beg to differ with her take on suicide. “Clever girl, I thought to myself when I first heard the news,” she writes of the suicide of a 49-year-old fashion designer. Merkin is certainly bolder and clearer than I am. When a teenage relative took his own life, “kind” and “clever” were my farthest thoughts. His mother’s and sisters’ irreducible pain were probably what first came to mind, followed by an unsuccessful struggle to put myself into his head: why, why, why? Three years later, nothing’s changed. His death is still a black hole.

Perhaps suicide resists any categorization. Each is sui generis (“in a class by itself; unique.”) Any attempt to pigeonhole it is useless. If I were to read tomorrow that 62-year-old Merkin had taken her own life, I’d probably think “clever girl” too, giving her credit for thinking it through and through before the fateful act. Whereas if it were a young person, for instance, especially if I knew them, it would break my heart.

Artist’s impression of suicide net on Golden Gate Bridge (Official handout)

A few years ago, I wrote a column in response to the decision by the directors of the Golden Gate Bridge deciding to install 20-foot wide “suicide nets” on each side of the bridge (due to be installed this year.) The bridge is a suicide magnet; over 1,700 people have jumped to their deaths since the bridge was completed in 1937. “But won’t they just find another way to kill themselves?” was the question asked at the time of their decision. Probably not. Statistics in this country and Europe show that bridge nets and fences really do reduce suicide rates. This jibes with the fact that having a gun in your home doubles your risk of suicide: remove the ready means, and at least some deaths are prevented.

The reason I brought up GGB is this statistic: A 1978 study showed that 94 percent of 505 people who had been restrained from jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge during the previous 40 years were either still alive or had died of natural causes. That is, most would-be-jumpers changed their minds.

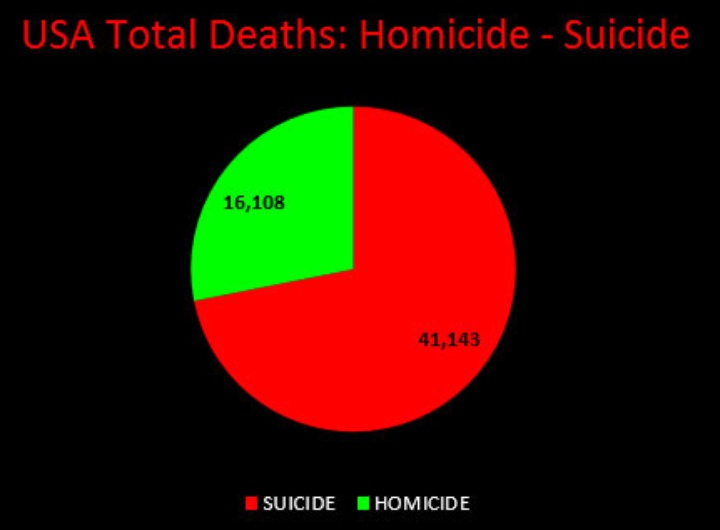

CDC data for 2014. On average, someone takes their own life every 13 minutes in the US. (Worldlife Expectancy)

Back to Daphne Merkin’s

“kindness” approach to suicide, shared, presumably, by

psychologist Thomas Szasz. In Suicide Prohibition: The Shame of

Medicine, he writes, “Killing oneself is a decision, not a

disease.” Sociologist Jennifer Michael Hecht takes the opposite

tack. In Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against

It, Hecht writes, “I’m issuing a rule. You are not allowed to

kill yourself.” Her rationale? None of us has the moral right to

end our own lives.

All of which is moot when you or I or someone close to us is contemplating it. “Moral right” doesn’t enter into it, unless, I guess, you’re a Medievalist convinced that committing suicide will result in a one-way trip to Hell. (Attempting suicide is illegal is some countries; it was a crime 50 years ago in Britain.) Complaining that suicide is a selfish act because it doesn’t take into account the pain caused to family and friends is probably another useless argument against it; guilt-tripping someone who is in the depths of despair probably isn’t going to brighten their spirits!

I’m attaching a list of resources because I think this is a hugely important issue, one that begs more discussion. Meanwhile I humbly suggest (1) we respect anyone’s decision to end their life; (2) we remove ready access to the means of doing so; (3) we move on from the “disease model” of suicide, with all the attached stigma.

Having said that, though: if faced with the situation, I would do (and have done, as a crisis hotline volunteer) everything in my power to talk them out of it.

Local 24-Hour Crisis Line (707) 445-7715

###

FURTHER READING

- Daphne Merkin, This Close to Happy: A Reckoning with Depression (Farrar, Straus and Giroux 2017)

- Thomas Joiner, Myths about Suicide (Harvard University Press 2010)

- Jennifer Michael Hecht, Stay: A History of Suicide and the Philosophies Against It (Yale University Press 2013)

- Tom Flynn, Less Secular Than It Seems—Review of Stay (Free Inquiry April-May 2014)

- Thomas Szasz, Suicide Prohibition: The Shame of Medicine (Syracuse University Press 2011)

- Kay Redfield Jamison, Night Falls Fast: Understanding Suicide (Knopf 2000)

- David Brooks, The Irony of Despair (NYT 12/5/13)

CLICK TO MANAGE