When my girlfriend’s father, the owner of a public house near where I lived as a teenager, caught Valerie and me making out on a bench in the local park, he ordered us to stop seeing each other. We were both 16 at the time. As I forlornly made my way back home in the darkness, I might have over-dramatized the sudden imposed break-up in my mind. Passing “The Bull” pub (not his pub), I imagined myself in the role of a spy who has narrowly avoided capture (spy movies were quite the thing in the 1950s), and did what he would have done. I strode in and ordered a double brandy.

Until then, my alcohol ingestion had been limited to low-alcohol lemonade shandies, so when ethanol from the fermented and distilled grapes hit my brain a few minutes later, I was, to put it bluntly, plastered. Which is the state my mum and dad found me in later that night. Not a good start to my future Adventures with Alcohol.

I suppose most every teenager has gone through such mortifications, ever since the fermentation of grapes (more accurately, the sugar in grapes) was invented some 10,000 years ago in China, traces having been found on old pots. A little later, the ancient Babylonians and Egyptians experimented with fermented grain. Like sex, the only way to know what effect it has is to try it. (And like sex, initial experiments are often disastrous. In my experience, anyway.)

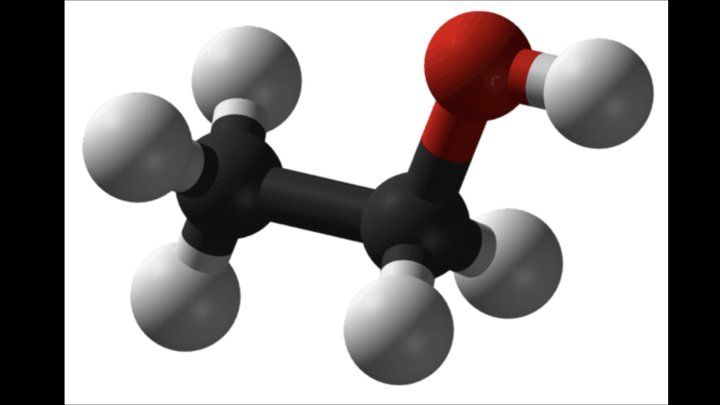

Good doggie.

Ethanol, C2H6O — the alcohol found in drinks — is popularly referred to as the “doggie molecule.” You can see why: two carbon atoms make up its body, with a single oxygen atom for a head and six hydrogen atoms for legs, nose and tail. It does its magic in our bodies and brains by virtue of being small — it can sneak into cells through otherwise impermeable lipid barriers — and water-soluble. The latter quality means it enters the bloodstream quickly from the upper intestine, from where it begins its romp through the whole person, top to tail. At the top — the brain — ethanol’s main effect is to empower the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA, hence slurred speech, slower reactions and unsteady gait down the sidewalk. It also suppresses glutamate, GABA’s opposite number — it stimulates rather than inhibits. With this double whammy to the brain, we are no longer captains of our own ships. (Aside from the negative consequences, alcohol is, of course, intensely pleasurable — that’s because it intensifies dopamine production in the brain’s “reward center.”)

Needless to say, none of this, had I known it back then, would have made any difference. In college in London, five or six pints of (British, strong) bitter ale was the norm for an evening out at a party or jazz club. You’d think a few nights spent crouched over the toilet bowl (a result of dehydration, another of alcohol’s many gifts) would have taught me better. But no, the only way out was to graduate from college. Not that this was a total fix — I ended up in New Zealand shortly thereafter, where 6-o’clock closing was then the order of the day. You, that is I, left work at five, raced down to the pub and drank as much as I could before last orders were called.

At some point, excessive beer consumption turned to the occasional glass of wine — occasional in this case being every evening — and all manner of experiments. I’ve been through my sherry phase, my Irish coffee phase, my Aperol phase, my Baileys phase, and am currently in my pre-bedtime Jägermeister (choice of frats, I’m told) phase. A bottle lasts a month, so we’re not talking excess. I hope.

The current medical consensus is that a single glass of wine a day (preferably red — the resveratrol, you know) is good for one’s health. I haven’t read about Jägermeister’s benefits, sadly.

CLICK TO MANAGE