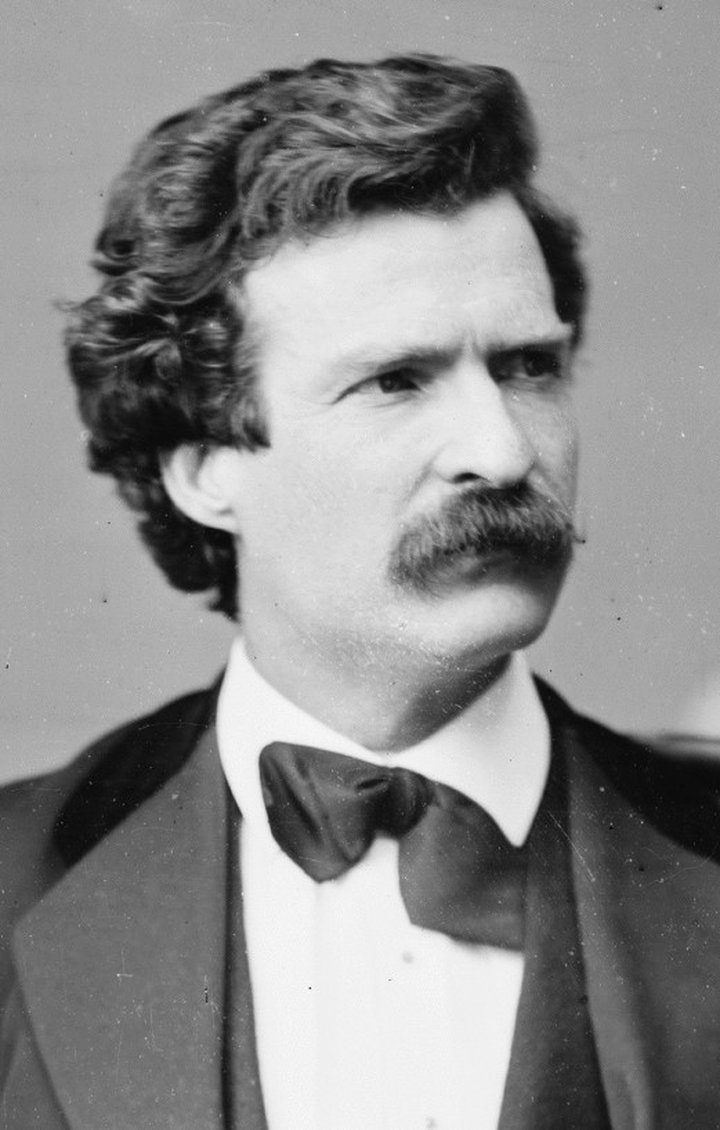

Studio portrait by Matthew Brady, public domain.

“A photograph is a most important document, and there is nothing more damning to go down to posterity than a silly, foolish smile caught and fixed forever.”

So wrote that master of literary humor and entertainment, Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) in a letter to the Sacramento Daily Union. Back then (“then” in this case being pre-1900) only children and sots smiled for photographs. “Solemn” was considered the appropriate expression for one’s photograph, at a time when a visit to a photo studio was a serious — perhaps a once-in-a-lifetime — affair. Invented in the late 1830s, the Daguerrotype process reduced exposure times for photographs from hours to, first 15 minutes, later under a minute — still a long time to hold a natural-looking smile, even if you were so inclined. (It probably didn’t help that the “cure” for unhealthy teeth then was to pull them — capping or replacing them was in the future — and no one wanted to be remembered with toothy grins.)

Author’s great-grandmother and mother, 1904.

Everything changed in 1900 with the release of Kodak’s first Brownie camera, which sold for $1 (about $30 today). The Brownie democratized photography: “You push the button, we do the rest,” was Kodak’s marketing slogan. It worked, 150,000 Brownies sold the first year. Kodak’s sales pitches included photos of everyday folks beaming, grinning, showing their lighter side for the camera. Later, silent film stars started having “happy” publicity photos, and soon everyone, from lowly workers to businessmen and politicians, was smiling for their photographs.

The Kodak Brownie 2 was manufactured by the Eastman-Kodak Company from 1901 to 1935.

Today, anyone caught in a photo with a serious expression just doesn’t get it (or is getting a passport or driver’s license). Photos and smiles go hand-in-hand — virtually worldwide. (Most cultures have an equivalent word for “cheese,” many using “little bird” in their language, as in “watch the birdie.”)

Yet consider how odd this is. We see a camera (or more likely an iPhone) pointed our way, and immediately change our expression from whatever it is at the time — neutral, frowning, anxious — to one of unadulterated happiness and joy. Does this parallel our usual cheerful response to “How are you doing?” (If you must know, not so good, given the state of the nation and the world.)

And once the photo’s taken, back we go to whatever our previous expression was. That is, our photos are completely unrealistic mementos of what we actually look like. We smile, what, 0.1% of our lives? A couple of minutes each day? Yet this is how we’ll be remembered after we’re gone. With those silly, foolish grins so abhorred by Mark Twain.

CLICK TO MANAGE